Tatiana Trouvé: Everything Flows, From Matter to Medium

Tatiana Trouvé. Courtesy Gagosian. Photo: Alastair Miller.

Tatiana Trouvé. Courtesy Gagosian. Photo: Alastair Miller.

Tatiana Trouvé's sculptures, drawings, and installations come together as an 'echo-system', with each work responding to the next.

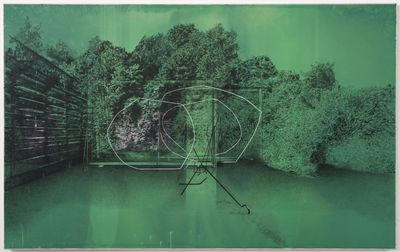

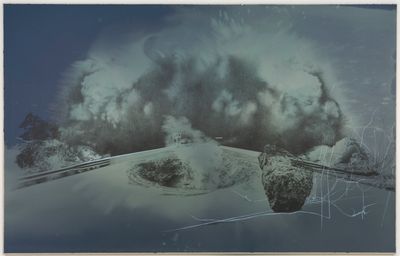

Fittingly, the line is a recurring motif throughout, connecting one thought or object to the next. Such is the case in her series of drawings 'Les dessouvenus' (2013–ongoing), in which sheets of paper are doused in bleach and inscribed with architectural structures and lines, creating blueprints for a fluid world, with no barriers or walls between inner and outer realms.

This sense of openness translates to Trouvé's installations, often to dramatic effect. At Gagosian in Beverly Hills, her exhibition On the Eve of Never Leaving in 2020 featured The Shaman (2018)—a bronze cast of an upturned oak tree, its tangled roots bursting through a pool of water within the fractured gallery floor.

Taking the exhibition's title from a translation of a poem by Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa that deals with the passage of time, Trouvé's installation gave an eerie sense of post-apocalyptic stillness. Surrounding the tree were cushions carved in marble, onyx, and granite—familiar objects rendered uncanny in stone.

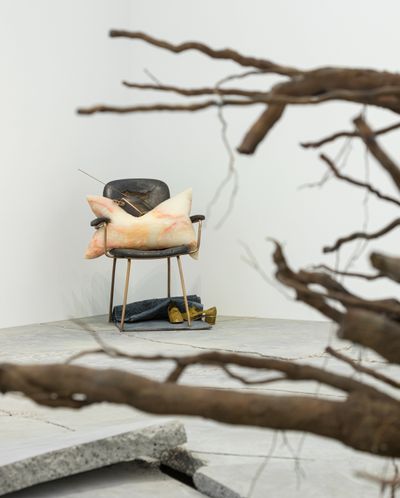

This dislocation between everyday vernacular and more intangible spheres was explored in Trouvé's installation The Residents (2021) at Orford Ness on the U.K.'s Suffolk Coast, a former military test site and now a nature reserve, where the group exhibition Afterness was organised by Artangel last year.

Once more including everyday elements such as chairs, blankets, and books, the different elements were installed amongst pools of water and weeds within the derelict interior of Lab 1, which was built for weapons testing in the 1960s. Accompanied by a large organic form resembling a scholar's rock, the installation combined the suggestion of a 'lost belief system' with elements suspended between the real and the fantastical.

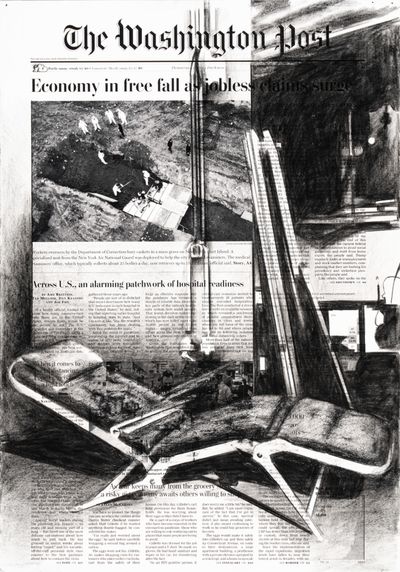

This duality is also present in Trouvé's recent drawings reflecting on the Covid-19 pandemic, titled 'From March to May' (2020), which were presented at Gagosian's New York space in 2021.

Combining inkjet-printed reproductions of international newspapers overlaid with drawings in graphite, ink, and linseed oil, Trouvé disrupts the text with new imagery, including stacked items in her studio, her dog, cushions, or a large leafless tree, reflecting the conflation of day-to-day realities with ungraspable world events.

Drawings are central to Trouvé's most recent exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (Le grand atlas de la désorientation, 8 June–22 August 2022), with the majority of them suspended from the ceiling, so as to appear floating in space. The exhibition opened alongside her latest solo show at Gagosian in Paris (8 June–3 September 2022), showcasing totemic sculptures alongside a wallpaper reproduction of L'Escamoteur (The Illusionist) (2022), shown in its original format at the Centre Pompidou—a drawing of faint stacked sheets residing within pools of bleached turquoise green.

In this conversation, Trouvé highlights the threads of her practice and her approach to creating an interconnected system of artworks.

TMYou moved a lot in your early years, from Italy to Dakar, Senegal, and then to France and the Netherlands for your studies. Did those early travels have an impact on your work?

TTOf course, the events of our lives influence us. Staying in different countries, speaking different languages, and being surrounded by different cultures provoked a strong feeling in me of not belonging to any particular community.

I often return to this phrase by Italian architect Ugo La Pietra, who said that 'to inhabit is to be at home everywhere.' For him, this means moving around and changing one's point of view.

The artworks that most impacted me were by artists who knew how to invent forms, concepts, or ideas departing from concrete experience.

I subscribe to this idea, which is dynamic and involves being interconnected with other things and beings. This idea is implicated in all of my work. One can view my drawings and installations as being linked to this question of interconnection, which is strongly implicated in the series 'The Great Atlas of Disorientation'.

TMYou studied at the Villa Arson in Nice and later the Ateliers '63 in Haarlem. What was your focus during this time and what were the key moments that set you on your track to connect material with ephemeral notions of time and memory?

TTDiscovering works by Alighiero Boetti, Eva Hesse, Edward Kienholz, Louise Bourgeois, Marcel Duchamp, and even Agnes Martin showed me that art does not have one designated form.

The artworks that most impacted me were by artists who knew how to invent forms, concepts, or ideas departing from concrete experience. I'm thinking here, for example, of Boetti's Lampada anuale (1967)—a standing box containing a bulb and the promise of light. We do not know the date, time, or even if it will light up, but it ignites a strong reflection on time and experience.

The artworks that interest me propose, in one way or another, an encounter with the unexpected.

TMBureau d'Activités Implicites (Bureau of Implicit Activities) (1997–2007) is a decade-long piece in which you documented your pursuit of a career as an artist. The installation is made up of 13 'modules', each dedicated to different aspects of your life, containing C.V.s, offer letters, identity cards, office supplies, and so on.

I am curious about your incentive to do this—what were you hoping to unravel as time went by? Or was it time itself?

TTThe Bureau of Implicit Activities was born out of my complete lack of means and visibility as a young artist. At the time, I didn't have a studio or money, and I was sustaining myself with informal work. I was asking whether an artist who cannot create or show work is still an artist.

I could engage in all the activities that accompany the realisation of an artwork—preparatory drawings, written texts, and so on—and through that, I inversed the course of things. My sculptures became shells or architectures collecting these pensive moments.

I dedicated a whole part of my work to 'inactive activities', such as striking or waiting, within the frame of a wider reflection on implicit activity. I do not subscribe to the binary opposition of activity and contemplation.

An artist has their own manner of approaching time, which combines intense activity associated with the material realisation of things within brief time spans—of a weld, for example, or a trace—along with the floating time of reflection.

The inherent temporality of drawing, which is a solitary activity, is not identical to that of sculpture, which engages a collective composed of artisans and assistants... Activities and thoughts nourish one another in the creation of this temporality.

TMI first encountered your work through your 'Les dessouvenus' drawings, which are made by plunging coloured paper into bleach before drawing 'environmental dramas' across them. You started these drawings about six years after Bureau d'Activités Implicites (Bureau of Implicit Activities), and they contain the signature elements of your sculptures and installations: lines connecting different elements.

Was this the first manifestation of that visual representation of interconnection? What had you been working on until then?

TTEverything I create is interlinked. My practice functions as a network, and within that network, the works shift between two and three dimensions. The sculptures can draw spaces in which they are positioned, and the drawings can sculpt spaces in which they are exposed.

I tried to create a visual journey—a circulation of works that separate and reconnect.

The materials and different elements can migrate from one form to the next. Taken as an ensemble, these elements create a kind of ecosystem. My drawings, sculptures, and installations echo one another—I could almost say that it's an echo-system.

I don't think my manner of working has changed very much over the years, but my position within these elements evolves constantly.

TMDrawing is a key component of your exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Le grand atlas de la désorientation. What was your approach to the space when conceiving the show?

TTI tried to create a visual journey—a circulation of works that separate and reconnect. This dynamic implies a kind of disorientation, but the installation permits the eye to wander and is articulated by physical movement. This develops in multiple dimensions, whether passing beneath suspended drawings, sitting amongst works, or walking on drawings on the ground.

I allow my works to temporarily inhabit and transform the spaces in which they are exhibited. The works 'install' themselves in the sense that they find their place where they are shown.

Gallery 3 of the Centre Pompidou is a kind of big glass cube. I put curtains on the windows, and between the windows and the curtains, I installed sculptures, which are silhouetted against the interior of the room. From the inside of the gallery, as a result of the shadows created by the curtains, the sculptures appear like drawings from the outside.

TMYour site-specific installations are awe-inspiring for their ability to transform the space they're in. Within white-cube spaces, you have had some radical installations, such as The Shaman, shown at Gagosian in 2020, consisting of roots from an upturned tree seemingly bursting through the concrete floor, from a pool of water.

Do you see the gallery as a blank canvas for such works? What challenges do these present for you?

TTI allow my works to temporarily inhabit and transform the spaces in which they are exhibited. The works 'install' themselves in the sense that they find their place where they are shown, modifying themselves discretely and sometimes more overtly to the places in which they are situated.

Of course, the white-cube space does not offer the same coordinates as a public park, but as a whole, I don't think there are any neutral spaces. There are only spaces to inhabit and transform.

TMYour installations often include concrete, marble pillows, or mattresses. Could you tell me about your decision to include these?

TTI often incorporate objects such as cushions, duvets, mattresses, shoes, cardboard boxes, and so on, into my installations and sculptures. These are generic objects from daily life that are testimony to a modest way of living. They have become the inhabitants of my works.

TMI understand The Shaman was one of the first instances you worked with water. How has that progressed since? Have you started incorporating any other new materials?

TTThe first time I used running water was with the fountain Waterfall (2014), and I also see The Shaman as a kind of sculpture. But I don't think we can restrain the question to the development of certain materials. All my work is based on the idea of time, not as a measure or in a chronological sense, but like a flow and an element of transformation.

I rely very much on Heraclitus' philosophical concept of 'panta rhei', which roughly translates to 'everything flows', because I think that the circulation of elements in my work reflects the reality of a world in constant movement.

The flow of material moves through my work, from one place to the next, for example, with drawings in the series 'Les dessouvenus', which are the result of splashes, stains, and drips of bleach on paper from which the drawings materialise. —[O]