Bill Henson

Photo: Jessica Hromas, courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

Photo: Jessica Hromas, courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

Faced with the daunting, but intriguing challenge of interviewing one of Australia's most distinguished artists, Bill Henson, I did the contemporary obvious — I googled him. The result was, as one would expect, slightly polarized. His recent withdrawal of work from the Adelaide Biennale following a police complaint had reignited the debate that surrounded the new infamous incident, which resulted in a police raid of his 2008 Sydney exhibition at the Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery. Pre-dominantly and refreshingly however, a majority of the search results did not descend into unfounded moral hysteria, but focused on the artist's practice, and his poignant and thoughtful contribution to art, and particularly photography.

One of Australian's pre-eminent artists, Henson was launched into the spotlight in 1975 with his first exhibition being held at the National Gallery of Victoria — he was only 19. Twenty years later he represented Australia at the 46th Venice Biennale. His work is held in all major Australian collections including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of South Australia, Art Gallery of Western Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and the National Gallery of Australia. Among international collections, his work is held in the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Denver Art Museum; the Houston Museum of Fine Art; 21C Museum, Louisville; the Montreal Museum of Fine Art; Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris; the DG Bank Collection in Frankfurt and the Sammlung Volpinum and the Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna. Major retrospectives of Henson's work at the Art Galleries of New South Wales and Victoria in 2005 attracted more than 115,000 people, and his work has also been studied widely in Australian schools for many years.

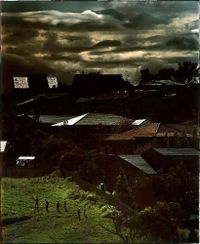

Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne recently opened an exhibition of Bill Henson's photographs,Untitled 1985/1986. The exhibition presents a selection of work from a series of photographs that Henson did over twenty-five years ago; and are a reminder of the dedication with which he has used photography to explore the world, humanity and art throughout his career. The work represents a selection of images from his Suburban Series and in it we can see the familiar investigation of the smudged and blurred boundaries that exist between certainties — for example, literally in the shadow of both ascending and descending daylight and metaphorically in the moments between childhood and adulthood. Using more often shadow, rather then light, to create uncertainties and complexities within each image, Henson has created a photographic monument to the ordinary beauty of suburban life. In the wake of that opening and as a two part series, I spoke to the artist about his practice and career. In Part One, the artist talks about his first exhibition, and his practice and approach to photography generally. In Part Two, Henson addresses a number of issues, including the status of a photograph, his interest in both lighting and curating his exhibitions, and his anti-portrait of Cate Blanchett. The artist also took the opportunity to provide a considered response to the recent controversy that again surrounded his practice following his decision to withdraw his work from the Adelaide Biennale.

ADPerhaps we can discuss a photograph's status as an object?

BHThis is quite interesting. Photography suffers more than any other medium from the mistake that people think when they've seen a reproduction of a picture either in a magazine or online that they've actually seen the original work. But there is a gap between a reproduction of a photographic image and the original form.

For me photography is about an object that just happens to be a photograph. So all of those fundamental and simple things like size, shape, and the physical presence of a sheet of paper are important.

ADIt is interesting to talk about the physicality of work because I understand you always prefer to curate your own exhibitions.

BHWhen given the opportunity to place work in a space I do want to curate the space. It doesn't make sense to me, when you have done everything you can to make a particular work as close to what you want it to be (in terms of its physical production) to then not be interested in how it sits in that space, or how it sits next to another image, or how images will face up against each other across a space. It's interesting to place works and see how different kinds of conversations open up between images. It's about the business of putting one thing next to another and getting a third thing. That interests me a great deal.

ADAnd does this extend to lighting a space?

BHIf you have the luxury of really curating the space you can also extend some of the feelings or ideas you have by controlling the light in the space. You can play with shadow and force the viewer to experience the image differently by manipulating the light.

It's a bit like looking at the history of sacred architecture. Across all of it — whether you are talking about longhouses, ancient monasteries, gothic cathedrals, or Egyptian temples — it is all about the controlling of light. It's about subdued light and the way you cannot experience or see the whole space or its parameters clearly at any time from any one position. I understand that and it makes sense. It is about drawing you on and making you move through a processional space. So when you have the great luxury, whether in a museum space or a gallery space, of modulating all of that then — just as you might be attempting something similar with a single image, you can use light to expand your ideas throughout an entire installation.

ADYour current exhibition at Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne features work from the Suburban Series. Tell me about this series?

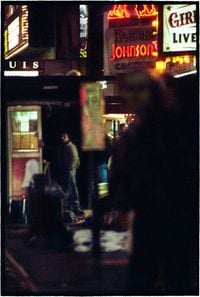

BHWell this is an unusual thing in that the exhibition at Tolarno contains work that was made twenty-six or twenty-seven years ago. I grew up in the suburban landscape in Australia and I had been thinking about how to photograph it for a long time. I have always found the suburbs very beautiful — the light, the change of seasons and so on. I am not so interested in the political dimensions of these things. I didn't have any witticisms to land on suburbia. I was really just interested in how beautiful it was. I felt it was like a dreamscape and once I understood that was how I needed to approach it the dream started to expand in unusual ways.

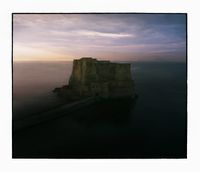

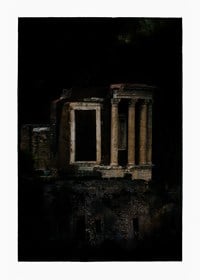

At the time I was taking these photos I was also taking photographs in Egypt of ancient Egyptian architecture and the two things started to speak to each other —a strange conversation started up. I realized that I wanted both the Egyptian architecture fragments and the suburban fragments to be seen at any equal distance or closeness, if you like. So the three bits in the original work were these Egyptian temples, people photographed in shopping malls and so on around Melbourne, and these sort-of uninhabited suburban landscapes. As I started to work with it things were revealed - conversations and equivalences started to unfold and I could see how it made perfect sense aesthetically and emotionally to have an image of a suburban house sit next to an image of an Egyptian temple, next to an image of someone standing in a shopping mall. So the original series, which had about 150 images in it, had those three components.

ADAnd why did you decide to just show the suburban images at Tolarno now?

BHJan Minchin, who is the owner of Tolarno, started to speak to me about four or five years ago about just showing a few of the suburban images — an exhibition about Melbourne in Melbourne. The work had been shown in many parts of the world — at the ICI years ago and the Pompidou Centre and here and there and everywhere else, but I hadn't hung any of these pictures for probably the best part of a decade and last year she said "Look I would really love to do this if you feel you can"; and I just sort of started thinking about it and decided it was quiet interesting to have just the suburban images. On a technical note too — because you know these were all shot on colour negative film - there was also a process of digitalising the negatives. I didn't want to change the images into something else. I was interested to see if I could bring the digital archival inkjet prints that I now make up to the same exact feeling and texture of the originals, and that worked out very well. I set myself a technical challenge to see if I could put them side-by-side and not see the difference.

ADYou recently photographed Cate Blanchett for Time Magazine. You call your portrait of her an anti-portrait. Can you please explain what you meant by that term?

BHI felt that there was an image I could make based upon the nature of the person. I wasn't interested in trying to make a picture that gave everyone a kind of mistaken idea that they might actually know something about her personally. With photography - and this is a general statement really, but it is a very important one - people need to understand the difference between intimacy and familiarity. It is absolutely essential to what I do. I feel that I have to make a picture which is absolutely intimate, but that doesn't come down to a mere sense of familiarity.

ADHow can you explain the different between familiarity and intimacy?

BHSo, the difference is easy to explain. If you are lying on the floor listening to music — now it might be Mozart or the Dead Kennedy's - you are having an intensely intimate experience, but it is in no way really familiar. This is a distinction that is absolutely critical when you make photographs — to understand how to bring an intense intimacy to something.

Standing in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna many years ago, I remember looking at Rembrandt's last portrait of his son, Titus, painted when he was about 21, and it is as though you can hear the breathe coming out of those parted lips. That kind of intense intimacy out stares history and it has a kind of millennial slippage, and it is the kind of thing you want to bring into a photograph. And so how successfully you can bring a deep emotionality to something without compromising the subject depends to a large extent upon understanding the difference between intimacy and mere familiarity. With Cate Blanchett, I wasn't presuming to know her well, because I don't. And I wasn't presuming to try and present her in a way in which people might feel like they know her well. It was an attempt to make something, which had an intimacy - but without any familiarity - and that is why I called it an anti-portrait.

ADWhen do you feel a work by you is complete? Is it when the public views the work?

BHI don't consciously anticipate an audience when I am working. Things gradually (or sometimes suddenly) arrive at a point where the picture remains interesting for me but there is nothing more I can do about it and so it's effectively finished. I only become aware of the audience when the work goes into the public domain. The trajectory of work in the public imagination is of course something that you cannot control. You are on the periphery of that. Sure you made the image, but once it has a public life, you are on the edge of it and people love it or hate it, or want to lock you up.

ADYou withdraw your work from the 2014 Adelaide Biennale after a police officer expressed his concerns that your exhibits could include 'graphic images'. Would you like to comment now on that decision?

BHThere are a couple of things that could be said about all this — and not just about the 2014 Adelaide Biennale debacle. Ideally we should want people to have, not just the courage of their convictions, but also a capacity for some kind of public display of self-respect so that they don't always appear to be focused on the lowest common denominator when negotiating difficult situations. It seems that, in public life, we've come to expect this 'race to the bottom' and the danger is that in viewing the world through this corrupting prism we end up short-changing ourselves in the process.

The seriousness and beauty of nature, which has always been the central concern of art - and naturally - always very much focused on the human form, is now routinely called into question or derided as suspect. We seem increasingly incapable of rising above a righteous prurience in public debate around matters involving the depiction of the human form. To see art's great moral and philosophical questions debased as the public imagination is hi-jacked by political expediency and its faustian bargain with the tabloids troubles me. When we succumb to this cartoon rhetoric we do ourselves a terrible disservice. There is so much that is compelling and humane and, yes, ambiguous and disconcerting but nevertheless deserving of serious attention in the art world. After all, art remains the one great constructive bridge between the subconscious and the conscious world. -[O]