Pinaree Sanpitak: Everything is Organic

Pinaree Sanpitak. Courtesy the artist and Yavuz Gallery. Photo: Tanapol Kaewpring.

Pinaree Sanpitak. Courtesy the artist and Yavuz Gallery. Photo: Tanapol Kaewpring.

Things have evolved organically for Pinaree Sanpitak. From a chance invitation to sit an exam that would take her to Japan on a scholarship at the University of Tsukuba, to the artworks that explore the body and its place in the world.

The title of the artist's solo exhibition at Yavuz Gallery in Sydney encapsulated two key themes that run through Sanpitak's practice: The Body and The Vessel (10 September–8 October 2022), which extended from a group of paintings on view at the 59th Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams (23 April–27 November 2022).

The Body and The Vessel presented new paintings and sculptures that evolved from Sanpitak's previous projects. The Affairs of Serving (2020–2021), for instance, is a large-scale installation composed of layers of stacked, hand-torn mulberry paper attached to the top of bottles and vessels placed on mid-century serving trolleys.

These vessels connect to the artist's installation for the 2019 Setouchi Triennale, for which she created eight paper sculptures for a village house on Honjima island, once the headquarters of the historic Shiwaku Navy.

These paper sculptures take the shape of the breast stupa, a common form in Sanpitak's work, which was also reflected in a series of wood sculptures for the Triennale paying homage to the island's boat-building tradition.

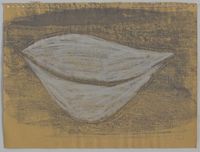

With its rounded base moving up to a central tip, the breast stupa form is an amalgam of the female breast and the rounded architecture of a Buddhist stupa. When turned upside down, its shape looks like a bowl or a vessel.

The form recurs across Sanpitak's work, including Temporary Insanity (2004), an installation of red, orange, and yellow pillow sculptures made from shimmering Thai silk, which contain motor propellers that rock their forms as they emit a humming sound.

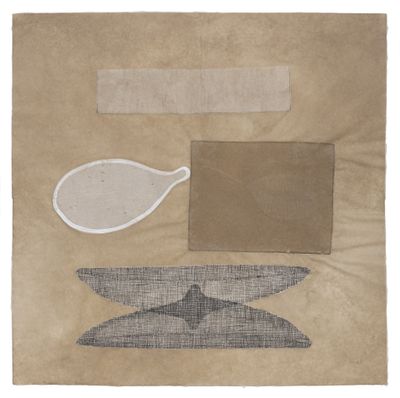

Sanpitak's new series of paintings connect to five paintings presented in Venice, defined by black, silver, white, and red colour schemes. But while in Venice these paintings feature a single vessel in a lighter shade than the tone of a monochromatic surface, Sanpitak's newer paintings combine the shapes of vessels, breasts, stupas, and bodies into one composition.

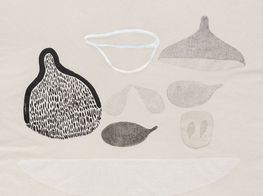

Some images are more recognisable than others. In the white-toned painting The Affairs of Serving III (2022), a large, shallow bowl stretches over the bottom of the canvas, above which hovers a flower, two breast stupas, and what seems like reeds—the only image not painted over, exuding a muted umber.

Then, there's a breast cloud form that combines the shape of a cloud and a breast on its side. When taken together, it resembles a few things; say, seeds, headphones, maybe mittens, or a pair of testicles. It really depends, and for Sanpitak, that's precisely the point.

Sanpitak has an openness that is communicated across all aspects of her practice, from the artist's use of materials to the way projects fold in and out of each other, to the legacy of the Silom Art Space, an independent artist-run gallery that Sanpitak co-founded in Bangkok with artist Chatchai Puipia, which ran from 1991 to 1995.

Born in Bangkok and having left Thailand to study in Japan, Sanpitak reconnected with the Bangkok art scene through the Silom Art Space. It was, as she remembers it, a place of fun and community; where connections, exhibitions, gatherings, and happenings were made.

Sanpitak is currently preparing to show two sound-interactive installations at the Bangkok Art Biennale (22 October 2022–23 February 2023): Temporary Insanity and Anything Can Break (2011–ongoing).

Widely shown since its first appearance in Bangkok in 2011 and the Biennale of Sydney in 2012, Anything Can Break is a monumental installation featuring a suspended sky of origami cubes and hand-blown glass clouds illuminated by fibre optics, with motion sensors picking up movement in the space activating musical notes.

With such a rich year of exhibitions to speak of, including a solo presentation with Yavuz Gallery at Art Basel Miami Beach in December 2022, Sanpitak discusses her major projects on view in 2022, while drawing out connections between them, and illuminating what they say about her life's work.

SBI wanted to start by asking you about the paintings you showed as part of The Milk of Dreams at the 59th Venice Biennale. Could you talk about those?

PSFor Venice, it was really fun to work on the wall I was given at the Arsenale because I got to hang the works in a salon style.

I had to make a composition that worked on that wall without knowing what was next to me or the position of the wall in the room. I tried to compose a story between the five paintings so that everything felt fluid and interrelated.

When Cecilia Alemani approached me and I read her themes for the Biennale—the body as a metaphor, the body and technology, the body as a vessel, and relating to the earth—I realised all these subjects relate to my work, and I was curious which works of mine Cecilia wanted to show.

It was decided that I was going to show paintings and not sculptures or installations, which I was very pleased about because it was unexpected. We selected five paintings from about 11 we experimented with, positioning them in different ways. Four of them are new works on canvas. The subject matter was up to me because all my works could relate to the themes: the body, the breast, the vessels, and the offering vessels.

SBThe paintings synthesise a lot of your installations and sculptural works, like the forms of The Vessel (2002) and Breast Stupa Topiary (2013), which you've shown more recently at the Setouchi Triennale and Jim Thompson Farm in Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand.

PSI've always worked between two and three dimensions, so they bounce off each other. My works are all related and evolve from one to the next. There's a thread that goes through them like a journey.

SBThat's a beautiful description of your practice. Would you say this journey began when you went to Japan to study?

PSI suppose you can say that. It was my last year of high school, and I was an exchange student in the United States. I came back to Thailand to prepare for university and a friend suggested that I take this exam for a full Japanese government scholarship. I just went for it without knowing any Japanese.

After a year of studying at the Japanese language school in Tokyo, I went on to the School of Fine Arts and Design at the University of Tsukuba. My recently published monograph covers the works I've created from 1985 to 2020, including those from the time I was in Japan.

SBHow do the new paintings you have created for The Body and The Vessel at Yavuz extend that journey?

PSMy early works were about perceptions and changing attitudes in how we perceive. This core idea continues in recent works. We had planned to do the show at Yavuz for quite some time, but with Covid-19 everything moved to this year. Some paintings at Yavuz are works that were part of the Venice selection. And because it relates to bodies and vessels, I titled the exhibition The Body and The Vessel.

Thinking about how the journey manifests in practice, the sculpture works showing at Yavuz evolved from this installation called House Calls from 2020 that I presented at 100 Tonson Foundation in Bangkok, which in turn started from these eight sculptures I first did at the Setouchi Triennale in 2019.

SBFor the Setouchi Triennale, you made paper sculptures that were shown inside this village house, then outside the house, you had these breast stupas made of wood, which were a homage to the island's shipmakers, right?

PSIt was on this little island called Honjima in 2019. The house I was allocated belonged to a carpenter, which relates to the island's history.

Honjima island was an important headquarters for the shogun's navy. The island has only around 330 residents now, mostly young kids and older people. I made the project as a homage to Shiwaku carpenters, local masters who are famous for making boats for the navy.

For the wooden sculptures, I thought about this boat-making tradition in connection to Japanese houses in the village, which are made of charred cedar wood. So I created Breast Stupa Topiary sculptures from charred wood, which were placed in the house's courtyard.

For the eight sculptures inside the house, I used paper sourced from Thailand, Korea, Laos, Vietnam, Japan, and China. They're hand-torn pieces of paper that are then stacked, with one needle in the middle connecting them.

I have three wonderful assistants helping me. To make each sculpture, we used a compass attached to a brush, then we wet the brush and made circles to tear each sheet of paper and show the deckle edges.

The first eight sculptures were placed on a pedestal, and I positioned them inside the tatami room of the house, which I painted black with charcoal and ink. As a homage to the lost masters of wood and paper, the eight sculptures sit in the tokonoma [raised alcove], where you would traditionally see a calligraphy piece or ikebana [flower arrangements].

SBAfter that, you created similar breast stupa paper sculptures like the ones you made for Setouchi Triennale, at the 100 Tonson Foundation in Bangkok.

PSWhen I was invited to show at 100 Tonson Foundation, I thought I could expand what I had done at the Setouchi Triennale to the domestic space, not knowing that we were actually going to be looking inwards because it was at the start of Covid-19.

I collect bowls, vessels, containers, and bottles, so for that project, House Calls, over 400 different pieces were made. They are constructed with that single needle through them in the centre, so a few pieces wiggled and the ones with round bottoms could move.

You couldn't see that if they were displayed on the floor, so I invited a design company in Thailand called Studiomake, run by American designer David Schafer, to help me design interchangeable and movable shelves upon which I placed the sculptures.

My works are all related and evolve from one to the next. There's a thread that goes through them like a journey.

Some of the shelves have a metal plate on the floor that is slightly bent. When people step on it, it bumps the legs of the shelves up, where the joints are connected to shake up the whole shelf. The installation makes you feel like you're at home, but there's this instability. You feel secure, but not secure, so there are all these emotions happening.

SBAnd then you continued these vessel sculptures for your show at Yavuz.

PSFor Yavuz, I wanted to continue with this medium and find a different way to make a moving base. I came across these mid-century trolleys that I found myself attracted to, maybe because we're from the same generation and they have a connotation of serving and connecting.

SBThere's something playful about the trolleys: these classic modern objects hosting ornate liquor bottles and paper vessels—it's a postmodern modernism.

PSIt's a trolley but you also have these strange objects on them, which adds layers to how the piece can be read. These bottles, bowls, vessels—you could look at them in terms of form and colour alone, or you might have a personal connection; it depends.

SBThe shape of these vessels reminds me of gourds, which made me think about the forms you've used for Temporary Insanity, which is one of the two early installations you will be showing at the Bangkok Art Biennale, right?

PSYes, Temporary Insanity and Anything Can Break will be shown at the Bangkok Art Biennale.

Temporary Insanity came about when I started using different materials in my work around 2000. I did a print workshop in Australia, which was a satellite project for artists after the Asia Pacific Triennial in 1999 that sent me to Darwin to work with print masters at Northern Editions. A lot of Aboriginal women artists also create works there and their printers are accustomed to working with non-printmakers.

I made a number of prints based on this sculpture installation called Womanly Bodies (1998) made from mulberry fibre and tried different printing techniques. I felt like I was cooking and had a wonderful experience feeling the different textures of the metal plate, stone, lithograph, and paper plates.

That was how I started to translate my works into different materials: charcoal, metal, wax, and so on. Then I made these candles, started to work with scent, and began wanting to incorporate movement and sound into my practice.

That was when Temporary Insanity came along. It was a year before I started Breast Stupa Cookery (2005–ongoing), a time I was working beyond the boundaries of womanhood and the confines of gender and becoming more focused on the human being, our emotions, and sensory perceptions that could relate to anybody.

Since then, my installations have become more interactive and immersive. Around that time, I created Noon Nom (2002), which filled a room with breast cushions that people could interact with but did not move on their own. Temporary Insanity followed, which is more about emotions; you can see the forms are breast-shaped, but some say they look like onions or pears. The forms have morphed into breasts and balls!

SBAcross your work, you take these common objects and explore their multi-dimensional properties by turning them into minimalist abstractions that can speak or connect to different things and people.

It's fascinating how that comes through in your materials, like the mulberry paper you found across Asia, or other types of paper you discover on your travels, like the Mohachi paper you sourced from Japan until the master who made it passed away.

PSI started using paper while studying in Japan. I was doing photography in the Visual Arts Communication Design department, but I did these mixed-media works with photographs and organic paper. I've always liked the contrasting elements and challenging materials.

My use of material happens spontaneously when I come across a material that I'm drawn to—as with the mulberry fibre. The fibre is from the first pounding of the bark before they make the paper pulp, so it's more fibrous. I was going to use them in my paintings or collages, but they were so beautiful and I didn't want to paint over them. I started sewing bits together and ended up making sculptures because they're very structural.

It's the same with Breast Stupa Cookery. When I wanted to incorporate food into the work, I thought of making sculptures with bread dough at first, as I was making bread a lot at the time, but it didn't feel quite right.

My use of material happens spontaneously when I come across a material that I'm drawn to.

Then, one day I was working with ceramics and it clicked. I thought I'll make these moulds and invite different chefs to work with them and interpret this form that I've been working on for so long into food. It's also my way of getting out of the art world. Now I have a lot of great chef friends and what better way to connect than through food? The chefs would come up with the menu with only a nudge from the Breast Stupa Cookery moulds.

Likewise for The Flying Cubes (2010–2011). A restaurant in Tokyo gave me an origami and I was very intrigued by it; a cube by itself is nothing, but a cube with wings opens endless interpretations. I folded the paper for two or three years before releasing it, first as scarecrows in rice fields of Chiang Mai for The Scarecrow project, and then as Anything Can Break.

I love paper and always go back to it. Because of Covid-19, it became difficult to order it from abroad. For the new trolley series, 'The Affairs of Serving', I've been mainly using mulberry paper from Chiang Mai.

Mohachi paper, which I've been using for some years, is different. The master who made it was from the Fukui prefecture on Honshu island. He had mastered a way of creating the paper so that you could print on it. The paper is handmade and very tight and dense. I use it to make drawings and other works.

SBWhere does your inspiration come from?

PSSometimes it comes from opportunities or themes that curators throw in or where I'm invited to make works. Then there's the site and the materials.

For instance, with the public installation The Roof at the Winter Garden Atrium in Brookfield Place, New York, I had planned to place mats and pillows on the floor but eventually raised the idea to the ceiling because of the foot traffic. Around the same time, I was asked to do The House is Crumbling (2017) at the National Gallery Singapore, which also deals with history and architectural elements.

SBLooking through your practice, you can see this organic throughline that develops through your work, from The Flying Cubes to Anything Can Break, which was shown at the Biennale of Sydney in 2012.

How have your ideas or approaches evolved? Or do the core ideas remain unchanging over time?

PSThe core is me; I see my works as biographical, like self-portraits. They follow what I do and experience—that's why I go back and forth between the forms and symbols I've created.

The first breast works I made in 1994 were made as monuments for womanhood—not only motherhood. Then they grew into bodies two, or three years after. Then I thought, maybe I'll go onto something else, but it was just so fascinating because it was my body.

I kept looking at it from different angles and placing it with different things, in other paintings, or with objects like 'The Affairs of Serving'. I made topiaries and placed them around the earth, the world, and growing plants. My works are short and long stories told through these artworks.

SBAnything Can Break, which you are showing at the Bangkok Art Biennale, was shown at the Biennale of Sydney exactly a decade ago.

Between now and then, how would you say the global conversation about art has evolved?

PSI was of a generation of artists that didn't have the internet, so everything was slower. And Thailand doesn't have any infrastructure to fully support art, whether galleries or backup from the government, which is still a problem.

I think artists from my generation had to learn to do everything ourselves; nothing comes easy and it's hard work. Our careers picked up internationally because museums in Singapore, Japan, and the APT in Australia shifted the focus to the Asia-Pacific in the 1980s and 90s.

I got opportunities to show internationally as curators started coming around. But showing in Bangkok was always important because it's my home base. One thing led to another—not that you need to become famous quickly. It's just part of my way of life. If I don't get to paint for some time, I get unsettled or uneasy. I need to do something with my hands.

I work gradually from one thing to another, and adjust both my personal life and my working schedules, like after having my son Shone, or when I separated from Chatchai and started travelling more.

SBWhat I'm hearing is that it doesn't really matter because the core of your work stays true to your personal experience of the world. But how do you respond when your work is framed a certain way, for example as a Thai artist or Asian artist?

PSI think you have to stand your ground because people will label you in any which way—as an Asian artist, a woman artist, or a mother. I was correcting a person the other day about why I started my breast works, which are not about the experience of giving birth, but breastfeeding and having breasts.

My work became more focused on the human being, our emotions, and sensory perceptions that could relate to anybody.

Another person thought that I kept doing these breast stupas because my mother had breast cancer and passed away. My mother is fine. She is 89 and does not have breast cancer. People have their thoughts and tend to categorise and label you—you can't control that.

In the late 1980s when I first started, I didn't want to use the word feminist because it was associated with different things. But yes, I am a feminist.

Generally, I just keep doing what I do and if researchers or curators are interested, they will start asking questions, though they tend to have some kind of running idea or theme.

Sometimes I do get carte blanche, as with STPI, which was a really fun residency. Around that time, I started doing the roof and the pillow works, and the forms became geometric, but they were still organic because of the paper and the way they were made. To be able to make these kinds of things with master printers and paper makers is any artist's dream. You never know the opportunities that come through.

SBWhen you did your residency at STPI, it was the first time the workshop made black paper pulp and you used the ebony fruit from Bangkok.

PSYes. We used fresh ebony fruit to dye textiles because we tried to make everything organic and the workshop did not have black paper. But because it was in Singapore, I had to send in dried ones, which we declared as tea. Then they crushed it. It does come out in varying shades, but I was very happy. I got them to try a lot of first things.

SBThose prints informed your most recent paintings, which you created for the Yavuz show, right?

PSLooking at what I am painting now, and looking back at how I was working at STPI three years ago, I can see that I have started to combine elements and forms into a single image.

At STPI, I had these printers making prints and we embedded the prints between layers of pulp, which had to be done in the wet room. That was the first time they did that. I was able to collage my works and ideas and compose them into a new work. And that process has transferred into my paintings, too. —[O]