Julie Rrap on Standing on Her Own Shoulders

In Collaboration with Melbourne Art Fair 2024

Julie Rrap with Write Me (2021). Exhibition view: Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Free/State, Art Gallery of South Australia (2022). Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Photo: Saul Steed.

Julie Rrap with Write Me (2021). Exhibition view: Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Free/State, Art Gallery of South Australia (2022). Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Photo: Saul Steed.

With writer Jennifer Higgie, the Australian artist discusses the evolution of her latest commission—a double cast of her body in bronze—and evaluates its place amongst four decades of feminist practice.

Julie Rrap has worked across performance, photography, painting, sculpture, installation, and video since the mid-1970s. Compelled by the human body and its representations, Rrap brings particular attention to the role of women in western art history.

Rrap spent eight years living in France and Belgium in the 1980s and 1990s, returning to Australia in 1994. Born Julie Parr, Rrap later reversed her surname in a gesture of defiance. She is the younger sister of artist Mike Parr, whose performances she assisted and participated in.

Rrap is the recipient of the 2024 Melbourne Art Foundation Commission. Her work, titled SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders), is a life-sized bronze sculpture that will be unveiled at Melbourne Art Fair next week, before travelling to the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney, where it will be included in Rrap's solo show, Past Continuous, opening in June 2024, and later to its permanent home in the collection of the Art Gallery of Western Australia.

Rrap said of the work: 'While SOMOS echoes the "heroic" tradition of bronze figurative sculpture, it subverts that history by representing an older female body traditionally rendered invisible,' describing its composition 'in which both casts of my body are caught in a moment of action as one figure appears to support the other on its shoulders'.

Disrupting such histories has been a centrepoint of Rrap's practice, whether through photography, as in the photo-mural Transpositions II (1994), or documented performance, as in Disclosures (1982). Rrap's affinity with photography in part lies in its nature as a popular medium, inextricably enmeshed in people's day-to-day lives; but also in its ability to mirror reality in variably distorted ways. Through performance and video, Rrap transforms these mirrored representations into unsettling realities.

JHCongratulations on your new bronze sculpture, SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders). I love the wonderful strangeness of seeing you stilled, standing on your own shoulders. How long have you been working on it?

JRI'd had this idea for about seven years, of depicting myself holding myself on my shoulders. I wanted to fuse classical sculpture with a detailed representation of my older body; most bronze figure sculptures are usually athletic males or idealised young women. But I hadn't gotten further than making a montage of it, and when I won it, I was like, 'Shit! Now I have to make it! An exciting challenge!'

JHWhat were the technical challenges involved?

JRThey were enormous! But I was recommended by my foundry, Crawford's Casting, to contact Claire Tennant, who specialises in direct body casting and worked out how to do it. It's important to me that it's a facsimile of me, which appears slightly uncanny with the softness of flesh transformed into metal.

JHWhat was the evolution of your thinking behind SOMOS?

JRSome ideas I labour over, but other ones like this simply jump into my head. I was thinking about the usual problem of women artists and their lack of historical visibility and about standing on the shoulders of giants, and then I wondered, 'Whose shoulders do I stand on?' In a kind of jokey way, I realised I have to stand on my own shoulders.

Humour is just one strategy . . . We can often laugh about things that we might feel uncomfortable to talk about more seriously.

As a monument, it needed to be in bronze in order to challenge the history of figurative sculpture, particularly one that is of an older female body. I think that's much more interesting from a feminist perspective because it alludes to a double invisibility—the representation of women artists historically, and the general societal view of the older woman.

JHHow did you arrive at the title, SOMOS?

JRSOMOS is an acronym, but also a palindrome which reflects the doubling of my body.

JHWhat's the focus of your upcoming show at the MCA in Sydney?

JRDisclosures: A Photographic Construct from 1982, a big photographic installation, is the first artwork I ever made, and it's in the collection of the MCA. I proposed that I could create new work in response to that installation and they loved the idea. The show will include a restaging of Disclosures and SOMOS and other works, which I'm in the process of making—I'm having a conversation with myself across the last 42 years.

JHCan you tell me about the title, Past Continuous?

JRI wanted the title to reference time, because Disclosures keeps resonating for me, both personally and because it's been written about so much as an important, early feminist work—it has gathered its own history independently of me.

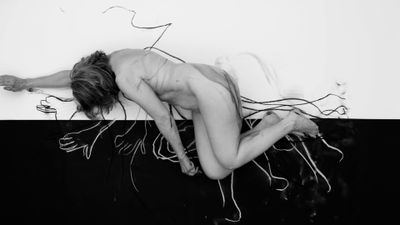

JHDisclosures is 60 black-and-white and 19 coloured photographic self-portraits, performing with a camera in various stages of undress. Often you feature multiple times in a single image. What was its genesis?

JRI spent two years making it in my tiny home studio in Sydney. I'd been reading a lot of Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes on photography, so it was very much a conversation with them. Sontag had some contradictory positions on the medium: on the one hand, she loved it, and on the other hand, she makes clear you can't ignore all of its other uses, many negative. I realised that the camera didn't really capture anything about me; I was just posing. But then it occurred to me that we never see the perspective of what the subject of a photograph is looking at, and so that became the device of the show.

JHThe installation of the work is crucial to understanding Disclosures. Could you describe it?

JRThe 60 paired photos reflect two concurrent views: in one, there's a tripod with a camera conventionally taking a picture of me as a nude, but around my neck is a camera. I would take a picture at the same moment that the camera on the tripod took a picture of me, so I shot a lot of really skewed photographs. So the model—me—is not just a silent presence but you get her perspective.

It was constructed so that the images hung in corridors with sightlines of me with a camera around my neck, so when visitors were looking at this young female body, there was always a camera looking back at them. It was an inversion of scoptophilia and how a camera looks voyeuristically at the body. I hired a space to display the work, took a month's holiday from my job and sat at the desk in the gallery, so there were always interesting conversations!

JHThe model becomes the artist.

JRExactly. That's why it's been written about a lot, because it's playing around with object/subject. But it's also completely playful—a sort of convoluted game about photography.

JHYou've always moved between mediums, from body art and performance to photography, painting, sculpture and video. How does SOMOS relate to Disclosures?

JRIt's a logical move, in many ways, because when I was making Disclosures, the images were printed from a negative from which you can make copies. It's the same process with sculpture, making a negative mould of myself. In SOMOS I'm doubling myself, and the corridors in Disclosures are also a kind of doubling.

Also, the stillness of sculpture—particularly bronze—relates to the stillness of photography, where things are infinitely held at a certain moment in time. SOMOS is a sculpture of me at 73 years of age and Disclosures holds me in my 30s.

JHIn many of your works since Disclosures—for example, the 2004 photographic series 'Soft Targets' and your 2022 exhibition, The Dust of History at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery—you've included naked self-portraits. What has been, and continues to be, your motivation for this?

JRIt's not a conversation about my body in particular. I use art as a way of thinking critically—there's nothing expressionistic about it. I'm not trying to explore a psychological space. It's more that I'm using myself as a vehicle to explore the representation of women. And, if I were directing another woman's body to do the things I wanted her to do, then I'd be falling into the old trap of someone having agency over someone else.

I used that as a metaphor for what I was doing with art history—I wasn't invited, so I had to break in and look around.

But you know, after 40 years or so of making art, in some ways it's only now that I can begin to make sense of what my practice is about. I've donated my body to the history of art as a kind of reflection on the fact that history can be very reductive and revisionist—I mean, in the first edition of Ernst Gombrich's The Story of Art (1950), he doesn't include a single woman artist!

JHArt history is full of naked women painted by men, but usually they're young. What are your thoughts on the representation of older women?

JRI've been hunting for them! Where are the sculptures, where are the paintings? Of course, you can find a few poor old wretches, crones, or witches, but that's about it! I'm definitely interested in pushing against a clichéd view of women's bodies within art.

JHWho were the artists who you admired when you were starting out?

JRVery early on, the only visible female artist I knew in Australia was Janet Dawson. I remember meeting her and was in awe. But I also got the impression that it was just all too hard, as she was one of the only women in a very male culture. I was part of a generation when women artists were beginning to be looked at properly, and it galvanised all of us to keep going. I loved artists such as Joy Hester, but there weren't millions of them—let's put it that way! A little later, I discovered Rebecca Horne, Cindy Sherman, Claude Cahun, and Valie Export. More recently, I love Sarah Lucas' cheekiness.

JHIs there a common denominator to the artists and artworks that appeal to you?

JRI often relate to artists in terms of their exploration of the body. I was introduced to Valie Export through my brother Mike [Parr]. Marina Abramović used to stay with Mike, and I lived next door to him, so I got to know her and others performance artists visiting Australia from Europe, such as Jürgen Klauke and Ulay.

When I lived in Europe, I became more interested in sculpture and loved artists like Juan Muñoz. You find your comrades in arms.

JHAll of these artists use disparate materials; it's not like you're attracted to a particular medium.

JRI like the kind of problem-solving that goes with being restless—I've always been that sort of artist. Although I think of my work as being photo-informed, it doesn't mean I'm confined to it as a medium. It's more like a thinking space. I've always been drawn to artists who move around different materials as they need to—I respond to the freedom of imagination in that.

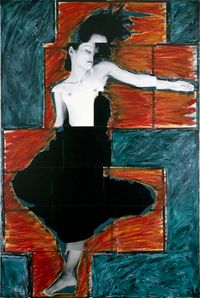

JHIn early works of yours, such as the hand-coloured Cibachrome print series 'Persona and Shadow' (1984), and the series 'Secret Strategies/Ideal Spaces' (1987), you referenced paintings of women by males artists, such as Edvard Munch or Édouard Manet. What's your relationship to them?

JRI think it'd be a stupid dismissal to go, 'Oh, they're just male artists', and attack them for that. Particularly Munch, whose work I really love. He was a convenient figure at the time partly because of the centralised way he used figures. He was also the default father of the new expressionism that was coming out in Germany and other parts of Europe in the early 1980s.

Throughout the 1970s so many women were making art and it was going beyond the boundaries of what art was at that time. It was exciting but a lot of it wasn't painting because I think many women artists viewed painting as over-determined by history; as a saturated space.

I made 'Persona and Shadow' in response to traveling in Europe. In 1981, I saw the exhibition, A New Spirit in Painting, at the Royal Academy in London—38 male artists, no women. Then in 1982, I visited the enormous Zeitgeist exhibition in Berlin at the Martin-Gropius-Bau. It was fantastic, but out of more than 200 artworks, only one female artist was included—Susan Rothenberg. And these were the shows that were meant to be ushering in a new decade!

I've always known that closing a door on something doesn't mean it goes away. I'd rather open the door, go into the lion's den, and confront it.

So when I returned to Australia in 1984, I made 'Persona and Shadow', playing mischief by using my body to disrupt stereotypical depictions of women in art history. I was reading Jean Genet's novel, The Thief's Journal (1949) at the time. He has a beautiful description of a thief breaking into a property, not in order to steal something but to occupy the space of the owner. I used that as a metaphor for what I was doing with art history—I wasn't invited, so I had to break in and look around.

JHWhen was the first time you cast your own body?

JRI was in living in Ghent in the 1980s and had an idea to make a sculpture where I cast the inside of my arms, down each side of my body, and between my legs—the empty spaces of the body articulated as negative forms. But I wasn't able do this work until I returned to Australia. The result was Vital Statistics (1997) which was made from silicon and fibreglass and accompanied by photographs of me performing in the sculptures.

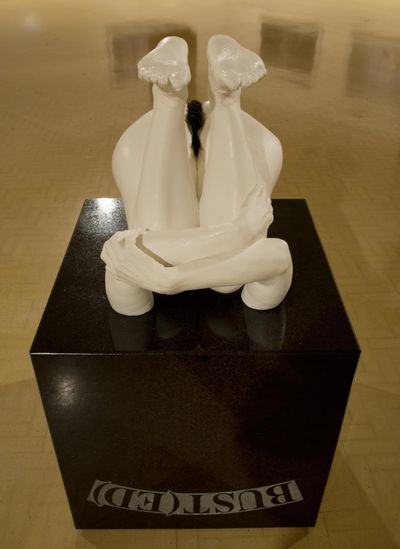

After that, I did a lot of works in fibreglass, rubber, and bronze. For the 2008 Sydney Biennale I made the sculptural work Bust(ed) which is basically my arse, split by a plait of human hair, with my feet in the air buried in this granite block. It's an amusing work that I'm quite fond of. It replaces a stereotypical bust of a famous person, usually male, with a woman's arse.

JHHow do you see the role of humour in your work?

JRI think it all started with the reversal of my name. In my family, at first, no one could believe I was doing that. You know, like, 'Is that a joke?' But I said, 'I'm doing it. I've done it.' I like humour and I knew from the start that if I went around ramming politics down people's throats, it would alienate them.

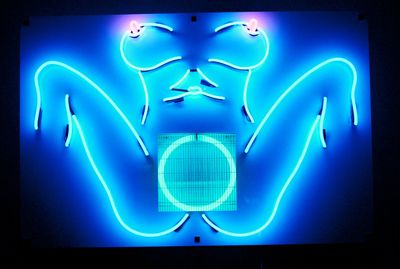

One of my favourite works is O (1999). It's a neon outline of a naked woman with her legs wide open and big juicy tits, and in the centre of it, I installed an insect zapper. It's a tribute to my late dad, who I was very fond of. He used to sell neon signs and insect zappers and he would have laughed his head off. But it's also a joke about Gustave Courbet's 1866 painting of a faceless, naked woman with open legs [L'Origine du monde] and Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés (1966). I love their work, and they could be my borrowed father figures, but again, it was my way of usurping history though the mundanity of the everyday.

Humour is just one strategy to explore serious stuff. We can often laugh about things that we might feel uncomfortable to talk about more seriously. I've always known that closing a door on something doesn't mean it goes away. I'd rather open the door, go into the lion's den, and confront it. —[O]