Jennifer Higgie on Crossing Thin Skin Thresholds

Jennifer Higgie in front of Peter Graham, A Cave in the Mind of a Shadow: My Memory of Looking Upon Mantegna's Rescue of Lost Souls from Limbo (2023). Exhibition view: Group Exhibition, Thin Skin, Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), Naarm/Melbourne (20 July–23 September 2023). Photo: MUMA.

Jennifer Higgie in front of Peter Graham, A Cave in the Mind of a Shadow: My Memory of Looking Upon Mantegna's Rescue of Lost Souls from Limbo (2023). Exhibition view: Group Exhibition, Thin Skin, Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), Naarm/Melbourne (20 July–23 September 2023). Photo: MUMA.

'Perhaps every good artist has thin skin; hypersensitivity is necessary to the creative act. How else to make nuanced images or objects in response to an often-abrasive world?'

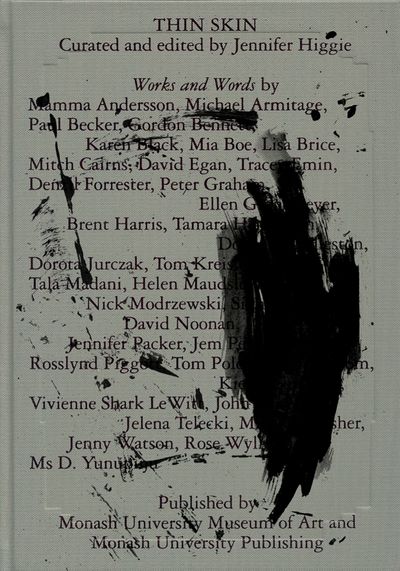

So opens Jennifer Higgie's essay for Thin Skin (20 July–23 September 2023), an exhibition presented at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) in Melbourne featuring 36 paintings that respond to the titular concept.

Curated by Higgie, the multi-hyphenate who led Frieze magazine's editorial direction for over two decades, the show is partly inspired by the research for her book, The Other Side: A Journey into Women, Art and the Spirit World (2023).

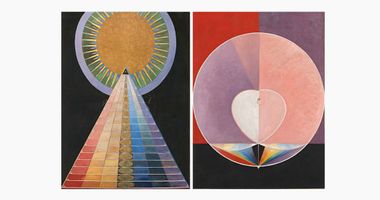

Fusing memoir, biography, and history, Higgie's book explores the influence of spiritualism in art history, delving into the lives and work of extraordinary women creatives such as 11th-century mystic Hildegard of Bingen and Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, who painted under the guidance of spirits.

While ideas that permeate The Other Side filter into Thin Skin, Higgie describes how the final exhibition also came together organically from studio visits and conversations with artists, some of whom are close friends.

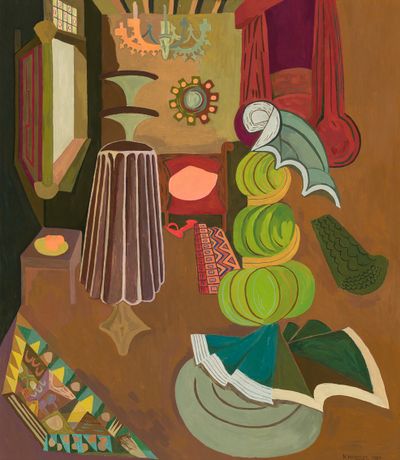

The result is a large but personal and intimate show of modern and contemporary paintings by artists who explore liminal space formally, psychologically and spiritually. Their works evoke ideas around paint and surface, body and environment, conscious and unconscious states, and otherworldly possibilities.

Described by Higgie as 'time travellers, moving across the membrane of history', artists include international names such as Tracey Emin, Michael Armitage, and Rose Wylie, as well as well-known Australian-born artists such as David Noonan.

In the accompanying catalogue text, 'A Nervous Canvas: Sixty-Four Thoughts on Thin Skin', Higgie includes her musings, as well as those of artists in the show, in a series of numbered short-form notes. Under No. 16, for example, Higgie writes, 'Skin is both a border and an insulator . . . it is a container for a soul; bodies are temporary, mutable, discardable. Humans . . . are only a breath away from shedding their skin and becoming something or someone else.'; while under No. 9, she quotes Australian-born artist Karen Black:

I think about the thin skin crusted over the wet blobs of paint in the work, or the thin layer between the reading of the work and the actual meaning. It can be punctured or held taut, wrinkled or smooth like our thoughts.

The result is a beautiful collection of ideas from a range of voices, which speaks to the connections between works and reflects the different possibilities for interpretation.

Accompanying these numbered thoughts is an evocative short story by Higgie's close friend and writer, Chloe Aridjis, which revolves around a young woman revisiting a family home. The story has a pervasive sense of otherworldly, ghostly mystery: a lace curtain is referred to 'as a membrane trembling between the past and present', while a metal gate shuts with a 'witch's breath'. At its ambiguous conclusion, the reader is left unsure about the world they have just been privy to.

In this interview, which took place in the lead-up to Thin Skin's opening, Higgie discusses the show and specific works in it, elaborating on her research for The Other Side, and shares stories about her enduring friendships with artists and writers.

ADTell me about how this show came about.

JHCharlotte Day, who was MUMA's director, invited me to put in a proposal; from there, the show came together organically. It is partially inspired by my research for my book, The Other Side: A Journey Into Women, Art and the Spirit World. But Thin Skin isn't gendered, and I wasn't interested in curating something illustrative of an academic idea.

What The Other Side explores, and what the show touches on, is liminal space. Thin Skin explores the idea of occupying a position on both sides of a boundary or a threshold, for example, formal ones between abstraction and figuration, and psychological ones, such as between conscious and unconscious realms.

For this show, I was also thinking of the boundaries between humans and animals, and the thin skin that separates people from each other. And then the idea of paint itself as a thin skin on a surface, which is what paint becomes when you apply it. It can also refer to political or personal states and objective and subjective takes on the world.

A thin place occupies the threshold between the physical world and the one that hosts spirits, dreams, the afterlife—a place where the distance between earth and heaven narrows.

I wanted to include artists I find intriguing, moving, challenging, and operating in this space that I'm loosely describing. I am interested in how they respond to this idea of 'thin skin' from different perspectives.

ADWere many of the works commissioned specifically for the show?

JHIt's a mix of works that I knew of already and works that I discussed with the artists that they shared for the show or made specifically for it. I did many studio visits and spent a lot of time talking with artists. Mia Boe, Nick Modrzewski, David Egan, Tom Polo, Kieren Seymour, Tamara Henderson, and Donna Huddleston all made work for the show.

I also asked David Noonan, a close friend of mine, to make a work for this show. We studied painting in Melbourne together in the nineties, and we moved to London together and shared a house. He made a painting for the show, Reverie (2023), and he has a show at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney called MASKEN(21 July–19 August 2023).

ADWhen you first started to pull this show together, was there one work you considered essential to it or that you began with?

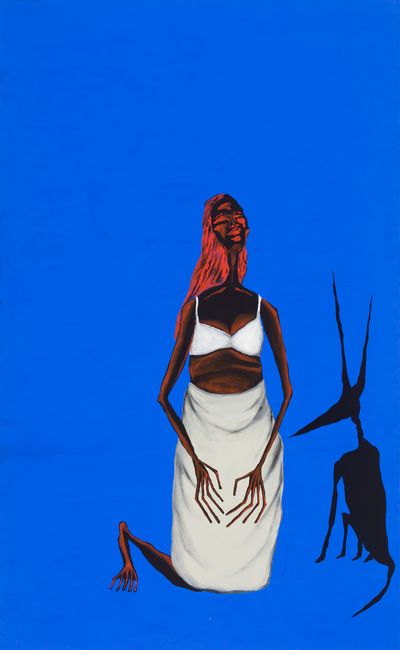

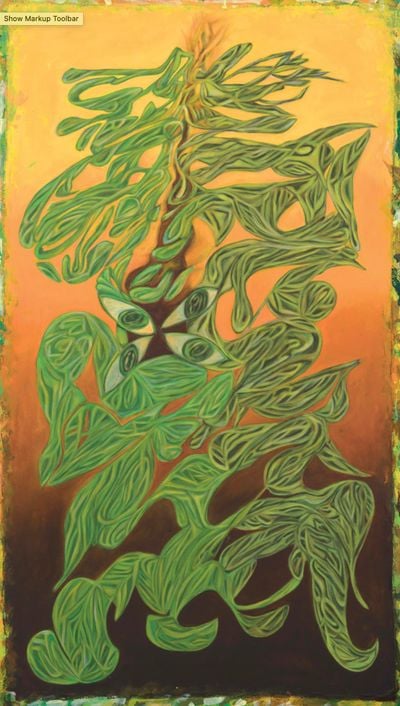

JHThere were a lot of works I thought had to be in this show. But certainly, there was one by Peter Graham that I knew immediately had to be in.

When I started my research, I saw Pete, an old friend, in his studio. I was staggered by his work—it is so brilliant.

The work that had to be in the show is called A Cave in the Mind of a Shadow: My Memory of Looking Upon Mantegna's Rescue of Lost Souls from Limbo (2023). It's a huge painting that is partly autobiographical. Pete describes his work as a kind of absurd self-portrait showing the interior of an enormous head form when a specific memory came into being. In his words, 'the image displays like a cross-section of my head'.

It relates to him seeing an extraordinary Renaissance painting by Andrea Mantegna, Descent into Limbo (1492). It also relates to another experience Pete shared about a crisis he had as a teenager, which has inspired much of his work. Walking along the street, he saw his shadow refracted before him like he'd been splintered into many beings. He has also always been interested in magic, and in Mantegna's painting, this magical figure is preparing to descend into an underworld.

I was interested in this idea of the thin skin between the present, the past, and the future—how one always affects the other. Pete was looking back to being a teenager and having a sort of crisis of self, but he was also looking back to this experience of seeing Mantegna's work, and he was trying to understand this all against the context of the pandemic—during this terrible crises moment when he painted the work. Many of Pete's paintings could have been in the show, but I thought this was a particularly extraordinary one.

ADYou talk of this connection between past, present, and future. In curating this show, it sounds like you were delving into your past, speaking with old friends and bringing their work together to create a show for the present.

JHAbsolutely. The selection process was very organic in that I spoke to artists and listened to what they were interested in. Many of them suggested artists whose works are in the show as a result. For example, Mitch Cairns told me about Tom Kreisler, a brilliant Argentinian-born New Zealand artist.

ADMany artists in this show work in Melbourne, but there are also artists from overseas, like the British artist Rose Wylie.

JHRose is now in her late eighties, and if you live in Australia, you may have only seen her work in reproductions, so I thought, how wonderful if we could get a work here in the show. I produced a video on Rose Wylie in her Kent studio in 2013. She is a wonderful person, and she was excited about this show. She made a painting for it, Wet Concrete and Thin Paint (2022).

ADThin Skin is the show's title, but the idea of 'thin places' also comes up. Can you discuss this concept?

JHWhen researching The Other Side, I came across the concept of 'thin places'. It's a vague term, and it isn't entirely clear where it originated, possibly in English or Celtic mythology. It refers to locations with unique or peculiar energy—magical places.

A thin place occupies the threshold between the physical world and the one that hosts spirits, dreams, the afterlife—a place where the distance between earth and heaven narrows. In thin places, the ephemeral is made tangible. It is a place where the veil between this world and the eternal world is thin.

ADSpeaking of different realms, in The Other Side, you talk of experiencing a ghostly presence, which seems to have impacted you.

JHI grew up Presbyterian, but I've never been particularly religious. I have always been interested in and open to the idea that the world has different kinds of energies. I don't know anyone who hasn't experienced coincidences or strange prophetic dreams or had a sense of knowing someone immediately—just quite vague things.

When I was around 20 and in undergraduate art school in Canberra, I lived in this house with a group of girls for a year, looking after it for a professor of anthropology. When the professor handed us the keys, he said, 'I think there is something you should know'. He explained that the house was haunted by the man who built it and died in one of the rooms in the 1920s.

The act of making art is in itself a sort of alchemical transformation—it's turning one thing into another.

We thought perhaps he was a little mad, and we were not worried at all. It was a beautiful, sunny, cheerful house full of beautiful art. But weird things happened—thumps on the floors, bed springs squeaking, a bookshelf moved across a room. It was pretty extraordinary. Not scary—just odd. A lot of the mysterious sounds happened during the day. The professor told us that this was quite a playful ghost.

Physicists say that we don't really understand what time is—that it is possible time isn't linear; there could be tears in the fabric of time. You can't study art history without being aware of spirits, ghosts, angels, gods, transformations, and so on—these things have significantly impacted the history of art. The act of making art is in itself a sort of alchemical transformation—it's turning one thing into another. So this idea of other realms has always interested me.

ADThe Other Side delves into the influence of spirituality on art history.

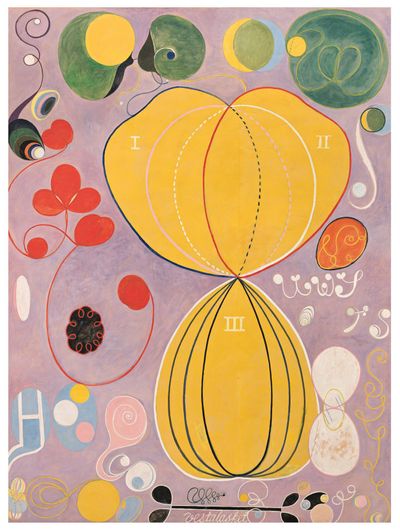

JHWhen you look at the early innovators of so-called abstraction, they were influenced to varying degrees by spiritualism, and many were fascinated by Theosophy. Wassily Kandinsky wrote Concerning the Spiritual in Art in 1910, and Piet Mondrian had a lifelong connection to spiritualism and philosophy. Paul Klee was interested in spiritualism too.

These artists were included in Alfred Barr's Cubism and Abstract Art in 1936 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was the first significant exhibition of Barr's that focused on the formal idea of abstraction, but it overlooked the influence of spiritualism. He famously said that 'artists had grown bored with painting facts... they were driven to abandon the imitation of natural appearance'. That couldn't have been further from the truth.

Were they saying that spirits were dictating their hand? Perhaps as an excuse for making the works they made. Maybe it was easier to say you were just a vessel.

Barr's statement opened up the idea of formalism and ignored the idea that abstraction might be a form of more complex representation—a means of representing an inner world, for example. In many ways, Barr tried to excise the history of spiritualism from the origins of these artists' works. And the idea that people like Clement Greenberg were propounding was that Western Modernism was about rationalism, about anti-religion. It was a clean, sleek, reasonable new world where art moved its colours and form around to express something rational.

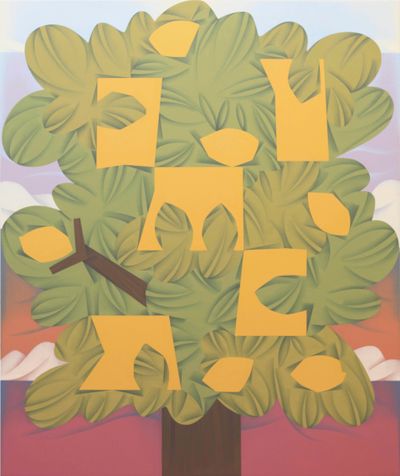

ADThe Other Side looks at artists like Hilma af Klint, who were making work and were very much influenced by spiritualism, but whose contributions were overlooked.

JHWe now know that art history is not carved in stone. It's a work in progress, and now we are looking at the contributions of pre-Modern artists like af Klint and Georgiana Houghton. Many women artists in the 19th century were dabbling in and influenced by spiritualism. Women's interest in spiritualism can be connected to the suffrage movement. At the time, women had so little agency. They didn't have the vote; they were not allowed to work or have their own money, and so on. They would form these female-led spiritualist groups where they had some autonomy. Were they saying that spirits were dictating their hand? Perhaps as an excuse for making the works they created. Maybe it was easier to say you were just a vessel.

For the book, I was mainly doing my research in and around London; however, spiritualism had an impact on artists all around the world. I gave a talk at the National Museum of Australia. After the talk, Jenny McFarlane gave me her book, Concerning the Spiritual: The Influence of the Theosophical Society on Australian Artists: 1890–1934 (2012). I wish I'd had it when I was researching my book. It's about the influence of the Theosophical Society on Australian artists. It's fascinating. So many early modernist Australian women artists were influenced by spiritualism. I touched on this lightly in my book, but I realise there's a bigger story to be told.

ADOne of the threads relevant to The Other Side and Thin Skin is the idea of magic. You talked about Peter Graham being interested in magic. And the award-winning writer Chloe Aridjis, who holds a doctorate in 19th-century French poetry and magic from the University of Oxford, wrote a short story for the catalogue. Can you discuss how Chloe came to contribute her story to this show?

JHChloe is a close friend of mine. She's an extraordinary novelist and thinker; her father is the famous Mexican poet Homero Aridjis. He was good friends with the great surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, and Chloe grew up going to Leonora's for afternoon tea. She has this incredible flat in London, which is crammed full of books, paintings, and sculptures, including Leonora's work.

Chloe straddles the worlds of magic, surrealism, and literature. I thought it would be wonderful for her to write something strange and evocative. I sent her my essay and images of the 36 works in the show, and she wrote a short story inspired by these images. It is a beautiful response to the works.

ADYour essay for the catalogue is titled 'A Nervous Canvas: Sixty-Four Thoughts on Thin Skin'. Tell me about this title.

JHI loved the idea of the 'nervous canvas'. I came across this amazing research project, a sort of speculative meditation on the idea of thin skin, by art historian Mechthild Fend on the history and representation of skin in 18th- and 19th-century France. It described medical texts from the later 18th century characterising skin as 'nervous canvas', which could be associated with Jean-Honoré Fragonard's 'Portraits de fantaisie' ('Fantastical Portraits') series, mostly dated 1769.

ADThis show feels very intimate and personal. Another person involved in Thin Skin is your sister Suzie Higgie. Her band, Falling Joys, has a song called 'Jennifer'—about you, I assume?

JHYes, that song is about me. I have dedicated my book to her too.

ADHer music introduces your podcast Bow Down, and she has created a soundscape for Thin Skin.

JHIt was an idea from the MUMA team, who suggested we commission Suzie to do a soundscape. She worked with musician Tim Oxley, and they spent a week composing while looking at images in the show. They came up with this wonderfully evocative sonic response to the works. It will be played throughout the galleries. I'm thrilled that Suzie's in it.

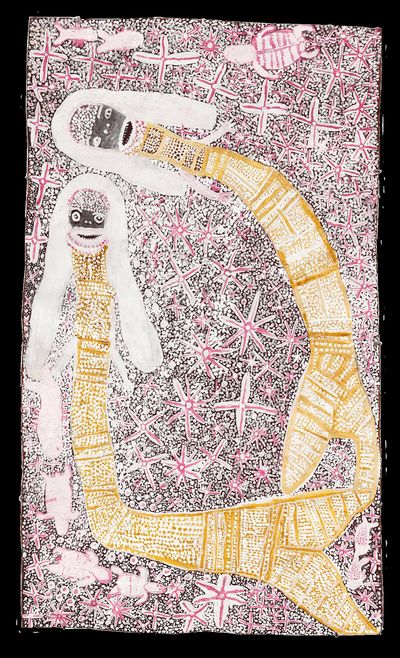

ADThere is an incredible painting by Ms D. Yunupingu in the show. Can you discuss this work?

JHPeter Graham told me about this amazing show, Bark Ladies: Eleven Artists from Yirrkala (2021), at the National Gallery of Victoria, which featured artists from Arnhem Land. I hot-footed it to that show which blew me away. As a result, we have work by the late Yolŋu elder Ms D. Yunupingu in Thin Skin. (As she passed away last year, she is only referred to now by her surname.)

Her painting Two Sisters Together (2021), made of earth pigments and recycled toner ink, gave me shivers. It tells the story of her conception as a mermaid and her family's journey in canoes from Marchinbar Island to Yirrkala in East Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. She explained:

'One day, my dad sees the tail of a mermaid and thinks he has seen a fish, so he walks closer and closer and closer and silently puts the woomera into the spear ready to throw. He throws the spear at the mermaid, but she jumps into the water . . . Later when he gets home and lies down and falls into a deep sleep . . . In his dream, he sees the mermaid and realises it is no ordinary fish.'

On waking, his wife confirmed she was pregnant, and they understood the mermaid was the spirit of their unborn daughter, Ms D. Yunupingu.

Thin Skin feels like a very large conversation, with one thing leading to the next. That has given me a lot of joy. It was less about me deciding what would be in the show and more about being led by artists to find out what should be in it. I think it has created an interesting conversation between generations, cultures, and works. —[O]