Nicholas Cullinan on Steering the National Portrait Gallery

Nicholas Cullinan. Photo: © Zoë Law.

Nicholas Cullinan. Photo: © Zoë Law.

This line, delivered by a Sicilian nobleman during the Risorgimento—the 19th-century movement for Italian unification that sparked a transition from the old order to a democracy—is one that Nicholas Cullinan now cites after taking the role of director at London's National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in 2015.

'If you love institutions and value tradition or history, you have to make sure that it's constantly reinventing itself at the present moment, so that it will survive,' Cullinan says. And he has done this with marked success, breathing new life into the institution through an engaging programme spotlighting hard-hitting artists while preserving its spirit.

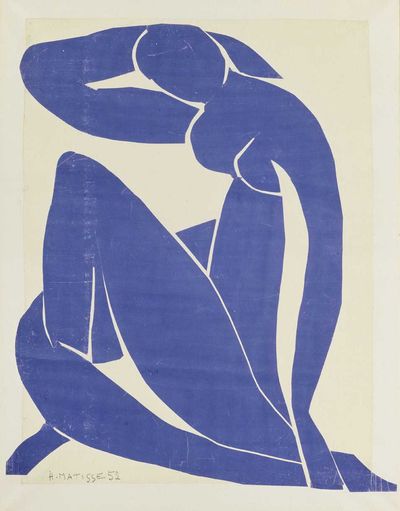

Prior to the National Portrait Gallery, Cullinan worked as Assistant Curator (2007–2009) at Tate Modern under the watchful eye of Nicholas Serota. The mentorship turned partnership (with Cullinan becoming Curator of International Modern Art) saw the pair roll-out exhibitions such as Cy Twombly: Cycles and Seasons (2008), Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye (2012), and the blockbuster Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs (2014). The Matisse exhibition was the most visited exhibition in Tate Modern's history, and spawned from posters of Matisse's 'Jazz' series blu-tacked on Cullinan's bedroom wall when he was growing up in Yorkshire.

After a two-year stint in the United States as Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at New York's The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cullinan returned to Britain to lead the National Portrait Gallery, taking over from Sandy Nairne after his 12-year tenure.

Cullinan's appointment was a sort of homecoming. Twenty-odd years ago, he walked the galleries as a security guard on Thursday and Friday nights to fund his studies at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

As the final two exhibitions of 2023—David Hockney: Drawing from Life (until 21 January 2024) and the Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize 2023 (until 25 February 2024)—open at NPG, Cullinan reflects on his years working with Twombly, the art of his transformative re-hang, and fashion designer Miuccia Prada's questioning of orthodoxy.

ADAlongside Nicholas Serota, you curated the 2008 Tate Modern exhibition, Cy Twombly: Cycles and Seasons and Twombly and Poussin: Arcadian Painters at Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2011, both in London. What was it like working with Twombly?

NCI was very young but aware at the time what a special and great privilege it was to work with him. He was an extraordinary artist and person.

The Dulwich Picture Gallery show sadly opened the week that Cy died. Pairing him with Poussin was probably quite surprising as you wouldn't necessarily think of those two artists together, but Poussin was one of Cy's favourite artists. There were some very interesting parallels between them, such as their devotion to classical antiquity.

I also learned a lot from Cy. He taught me about what really matters, about longevity, and how to keep your focus on the right priorities rather than get distracted by things that really aren't important. It was a real education at an impressionable age.

ADAt Tate, you also spent several years working with Nicholas Serota, who is a legendary figure in the London art scene.

NCNick has extraordinary discipline and focus. Like Twombly, he was focused on the right thing, which is primarily art and artists. In terms of being a museum director, Nick is sort of as good as it can get.

ADWhat lessons from him did you take with you to NPG?

NCI think it's important to note that you can never, nor should you ever, fully emulate someone. What is right for one person might not necessarily be the right style or approach for you. You have to figure out your own way of doing things.

What I think you can emulate, or rather admire, is someone's qualities. It's about diligence, having the right priorities, and doing things for the right reason.

ADYou've been at NPG since 2015, and this year headed up the re-hang, which has been met with a great response. How do you modernise such an old institution?

NCWhile there's obviously the re-hang, it's also about the complete transformation: the building, the brand, the museum's visual identity, and what we do in terms of exhibition programmes.

When I started almost nine years ago, I had a very clear sense of what I wanted to do. However, how you get there may not always be linear, and it's definitely not overnight. Rather, it's a question of gradually figuring out how to change things, while keeping the best of what's there.

There's a great quote by the Italian author Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa in his novel, The Leopard, which is about the Sicilian aristocracy and how these great families and houses survive or decline: 'If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.'

It's also true of institutions. If you love institutions and you value tradition or history, you have to make sure that it's constantly reinventing itself at the present moment, so that it will survive. The tension between how you preserve something, while ensuring it's still relevant and reaches new audiences is an interesting balance.

ADWith this revamp, what role do you see the National Portrait Gallery playing in the contemporary London art scene?

NCI think it's even wider than just London or the art scene. Given our remit since our founding in 1856, the National Portrait Gallery should be at the centre of conversations about Britain: what Britain is, its history, who makes it, and how that is changing.

We're in a unique position as we're not just about art and artists, but also about the sitter and therefore biographical history. We have always been very keen not to change the gallery into something else, but to affirm what's unique about it.

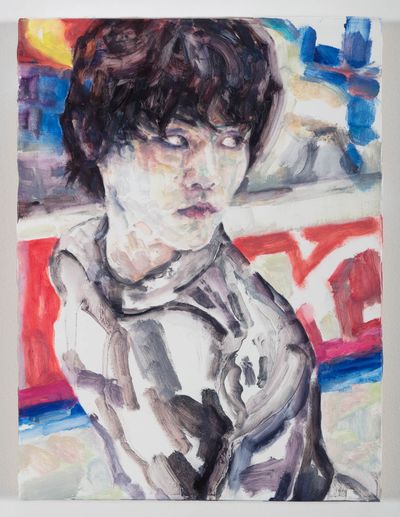

ADYou've re-energised the museum by spotlighting hard-hitting artists such as Elizabeth Peyton, Cindy Sherman, and Tacita Dean. How hard is it to balance a programme that's cutting edge but also accessible?

NCIt's not hard if you start with the right intention. I never think about whether an exhibition is going to be a blockbuster. Of course, certain names with big recognition and appeal are going to bring in more visitors. Start with an idea, execute it as well as you possibly can, and communicate it to the widest and most diverse audience. That's the most important thing.

I think the Tate Modern exhibition, Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs is still the most popular in the museum's history, with over a million total visitors—500,000 in London, and around the same when it travelled to the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

That exhibition began with a very simple idea. When I was a teenager growing up in Yorkshire, I used to have packs of small posters that you could buy on Impressionists or Jackson Pollock on my bedroom wall, including Matisse's 'Jazz' series.

We did that exhibition for the immediate joy that these works brought. It seems that many people felt that, and that's why the exhibition caught on fire.

It works the same if you do an exhibition with an artist that's less well-known. People don't want to be given what they know all the time—discovery is important.

ADHave any exhibitions shocked you with their popularity?

NCWhen I started at the NPG back in 2015, I remember asking my colleagues about doing an exhibition of Nicholas Hilliard, the British painter famed for his miniature portraits. The gallery has a great collection of miniatures, but there hadn't been an exhibition for a while.

Despite an initial worry that miniatures were a thing of the past, we pushed on with the exhibition. Mounted alongside another miniature practitioner, Isaac Oliver, it did incredibly well, not just among older audiences, but the younger generation as well.

I think often when you're told things as orthodoxy, you have to question it. Over the years, I've worked with Miuccia Prada and her foundation in Milan. I think a lot about what she said to me once about her designs and art collection: 'I've never understood why things that are coarse and banal are meant to be popular, and things that are more refined and difficult are meant to be unpopular. All I've ever wanted to do with my fashion designs and my art collection is to make intelligent things attractive.'

And that's exactly what she's done. You can take something that people would normally avoid or find boring or unappealing, and if you communicate it and do something interesting with it, you can make it a desirable thing.

ADShould museums accept gifts from galleries, which are often stipulated for collectors to gain access to in-demand artists?

NCIt's important to remember that in the art world, we all work side-by-side. If you work for a museum, and you're doing an exhibition with an artist, or acquiring a work for the museum, you're always working with a gallery. Although I'm very happy to work with artists, galleries, and collectors, I would never do something because it was stipulated or because I was being pressured. It's important to have your own integrity and autonomy.

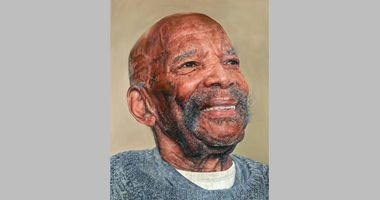

ADIs there a portrait in the re-hang that you catch yourself returning to?

NCMany jump out when I wander through—not literally, that would be scary. For me, the amazing Portrait of Omai (1776) by Joshua Reynolds included in the re-hang is an incredibly important work as it was a huge undertaking and, as such, an important acquisition.

However, there are also old favourites from when I was a student working as a guard at the NPG. In 2002, the NPG hosted an exhibition on 18th-century British portrait painter George Romney. I fell in love with Romney, and included his 1784 unfinished self-portrait in a show I put on at the Met (Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, 2016) on unfinished works, and now it's in the NPG collection.

ADYou worked as a guard?

NCLike many students, I worked all kinds of part-time jobs when I was studying at the Courtauld. When I wasn't working at Boots Opticians on Kensington High Street, I worked at NPG on Thursday and Friday evenings.

Between 2001 and 2003, I was a visitor service assistant, which meant I was basically in the galleries guarding the paintings and talking to the visitors. It was fantastic.

ADI loved that book All the Beauty in the World (2022) written by Patrick Bringley, a security guard at the Met.

NCYes, I've read it. It's very good. There's also a great film called Museum Hours (2012), which is set in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

There's something really interesting about being sat there for hours in a museum with often incredible works of art and people walking by. You're observing, while also being a bit invisible. I'd recommend anyone to do it, you learn a lot. —[O]