Patrick Sun: Collecting with Pride

Patrick Sun. Courtesy Sunpride Foundation. Photo: Amanda Kho.

Patrick Sun. Courtesy Sunpride Foundation. Photo: Amanda Kho.

Hong Kong-born collector Patrick Sun has been collecting art since 1988, when the launch of his real estate business led him to daily walks along Hong Kong's Hollywood Road, known for its antique storefronts and showrooms, where Sun developed a taste for Chinese painting.

One of the first works that Sun acquired was a painting by Qian Hui'an of two boys eating a stolen watermelon—a work whose connotations of brotherly love and forbidden fruit Sun describes as foreshadowing the Sunpride Foundation he would found in 2014 to support the rights of the LGBTQ community and its allies in Asia through art.

Since launching, the Sunpride Foundation has since worked on two major projects: Spectrosynthesis — Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now, the first LGBTQ-themed museum exhibition in Asia curated by Sean C. S. Hu and staged at Taipei's Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in 2017, and Spectrosynthesis II — Exposure of Tolerance: LGBTQ in Southeast Asia, which opened at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) in 2019. The Taipei show launched just as the High Court in Taiwan paved the way for the legalisation of same-sex marriage, presenting 51 works created by 22 artists from Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, and Singapore, over 50 years, from Tseng Kwong Chi to Samson Young and Wu Tsang.

Sun has talked about visiting MOCA to inconspicuously observe how visitors responded to the exhibition, and being especially moved by watching a mother describe Jimmy Ong's charcoal drawing of lesbian parenthood Heart Daughters (2005) to her son, explaining that in the world, 'there are men who love women, women who love women and men who love men.'

Sun, who has actively supported LGBTQ rights since 2002, would later describe 2017 as 'a year of liberation for the queer community—not just because of steps toward marriage equality in Taiwan and Australia, but also in the art world'. Marking half a century since the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain, institutions across the country staged LGBTQ-themed exhibition that year—part of a 'proliferation' of queer-focused exhibitions that year, which Sun saw as a testament to art's ability to trigger discussion, challenge norms, and 'help to change people's perspectives'.

It is on this ability that Sunpride Foundation's work in contemporary art is anchored: a mission demonstrated in Spectrosynthesis II in Bangkok, which was curated by a team led by BACC Chief Curator Chatvichai Promadhattavedi. Spectrosynthesis II was a more expansive affair in terms of regional representation, with some 100 works by 59 artists hailing from 15 countries across Southeast Asia. These included Anne Samat's Conundrum Ka Sorga (To Heaven) (2019), an androgynous figure shaped from woven materials and tags with the names of the artist's friends from the LGBT community; and black and white images from photographer Cindy Aquino's 'Bond' series (2013), which explores gender identities among lesbian women, and the bondage often worn under clothes to conceal femininity.

In this conversation, Patrick Sun reflects on his work with Sunpride Foundation, and what he has learned in the process of developing an institution that aims to open perspectives surrounding identity in Asia.

SBYou first started collecting in 1988 with an interest in Chinese ink painting. Could you talk about those early years, your first discoveries, and how your knowledge and understanding of art developed at this time?

PSMy first property development project was on Hollywood Road, an area in Hong Kong famous for curio and antique shops. Walking by these shops frequently got me interested in art. One of my first collections was Qian Hui'an's painting of two boys eating a stolen melon, which in retrospect, foreshadows my later interest in LGBTQ art. I have always supported gay rights movements, from fundraising events to participation in parades and pride activities. When I contemplated starting an art collection, I thought, why don't I merge the two interests into one? I see art as an alternative way to support the LGBTQ community, raising awareness and respect for gay people through collections and exhibitions. In 2014 I started Sunpride Foundation with a specific focus on gay Asian art.

SBHow did you make the transition from collecting modern Chinese painting to supporting LGBTQ-focused contemporary art through the Sunpride Foundation? Do you see these two parts of your collecting practice as connected, or do you see them as separate?

PSMy interest in traditional art gradually shifted, partly because of the difficulty in authentication, and partly because contemporary art seems much more relevant to my daily life. These two parts are largely separate, but not entirely so; for instance, in Qian Hui'an's painting I mentioned above and also in becoming friends with Sunpride's art advisor Mr. Michael Chen.

SBYou have said that the way you collect is geared towards staging exhibitions, with your criteria for acquiring work more focused on how a piece might fit into a show—was this always the case? Does this mean that you build your collection based on the shows you envision staging?

PSThe Chinese paintings were bought for personal enjoyment. With Sunpride's collection, it would always be purchased with a view to an eventual exhibition. For example, prior to staging the show in Taipei, our focus was more on local and Chinese artists. When we planned for the show in Bangkok, our interest shifted to Southeast Asia.

SBGiven the way you collect, do you see yourself more as a hybrid collector-curator, an organiser and activist, or something else altogether?

PSI like the word hybrid, because I don't know how to categorise myself, and also because it infers diversification and inclusivity: two values that Sunpride Foundation supports.

SBOn that note, I wanted to discuss the two major projects that you have staged with Sunpride Foundation: Spectrosynthesis at MOCA Taipei and Spectrosynthesis II at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre. How involved were you curatorially in the development of these landmark shows for Asia?

PSDrawing an analogy to making a movie, I compare Sunpride's role to that of a producer. The curator is the director, so our role is to help facilitate his or her vision. What we have in our collection is a starting point for the curator to build on. Ultimately, the selection is his or hers, and a lot of works are borrowed and commissioned to help put together a comprehensive and coherent exhibition.

I see art as an alternative way to support the LGBTQ community, raising awareness and respect for gay people through collections and exhibitions.

SBI read that the Foundation had amassed about 200 works when you first approached MOCA Taipei, and the curatorial team were invited to expand on the collection, with artworks from other collectors, museums, artists, and galleries also included in the exhibition. How did organising exhibitions in government-supported institutions compare to your experience of market platforms like auctions and art fairs? How do you think these networks might evolve in response to the current pandemic?

PSThe art world has gone digital at an amazing speed because of the pandemic. This process is both timely and necessary, and provides unprecedented opportunities for Sunpride Foundation too. Whilst we continue to organise exhibitions in public institutions—because nothing compares to experiencing art face to face—we shall also explore virtual engagements of our previous and future exhibitions, perhaps with a new direction of curation involving artworks that only need to be present digitally.

SBYou have said that working closely with artists is very important—you want to make sure they are comfortable being included in projects that could out them, put them at risk, or frame their work in ways that they did not intend. On the Taipei iteration of Spectrosynthesis, you mentioned a discussion with Samson Young about how his work could fit into the show, since it does not specifically address LGBTQ themes, ultimately agreeing on the video of a choir performing without sound in Muted Situation #5: Muted Chorus (2016).

What have been some of the most profound conversations and lessons you've had from working with artists around the themes and concerns of Sunpride Foundation, and how has this influenced your approach to leading the Foundation's mission?

PSWhen I first met Danh Vo, I was basically starstruck and couldn't help blabbering on and on about my take on his work We The People (2010–2013), seeking his endorsement on my interpretations of liberty and commercialism. And Danh, in his usual cool but friendly manner, told me that his works are meant to raise questions instead of giving answers.

I have since learned to look at artworks beyond the obvious, as well as from different angles. Going back to Samson Young's work as an example, we used Muted Situation #5: Muted Chorus to illustrate an atmosphere of political suppression. Looking back now at times of pandemic, the work can be seen from a different perspective, talking about how we need to focus on the overlooked and undervalued when the dominant voice is subdued.

SBSimilarly, I wonder how your work with artists and institutions across Asia has revealed the lived picture of civil rights for LGBTQ and non-conforming communities across the region. What is the outlook in Asia, taking into account your hope that more conservative Asian countries will host LGBTQ-themed exhibitions in the future?

PSThe road to social acceptance for the LGBTQ community is never easy. While setbacks are expected, I remain optimistic that the more conservative Asian countries will eventually realise that they don't want to stand on the wrong side of history. I am encouraged by what happened in India. A year ago, homosexuality was illegal there, and then Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was overturned by the High Court. I expect other countries in Asia who are keeping this archaic colonial law will follow suit.

SBThis relates to what you have learned from audiences. As you have said, 'The law is one thing, but social acceptance is another'. Both Spectrosynthesis shows were focused on speaking to a broad public by exploring issues that are enduringly common—like family, identity, and tradition—within government-sanctioned institutions in order to further the visibility and rights of marginalised groups. In recent interviews, you shared memories of watching a mother explain Jimmy Ong's work in Taipei and taking your elderly father to that show's opening, during which he said you must be doing something right even if he didn't understand the art.

Looking back, what have been some of the key lessons that you have learned from audiences of both exhibitions?

PSI am overwhelmed by the positive response from the general public. One lesson I learned is that you should never underestimate the intelligence of the public. In the struggle for legal sanction, we often hear government leaders making excuses that the moral majority is not ready for changes. In fact, it is up to a responsible government to lead the way for a more equitable society for everyone, including the LGBTQ community.

SBWhile both exhibitions were well received by art critics, some pointed out the relative disparity in gender representation, with a noted dominance of male-identifying practices represented; how might you respond to that point?

PSWe actually made a conscious effort to include more female and transgender artists in our Bangkok exhibition. In some cases, even though the artist is male, we tried to show works with female subjects as an overall effort to achieve a more balanced presentation. There is certainly room for improvement, and we shall continue to make such an effort.

I remain optimistic that the more conservative Asian countries will eventually realise that they don't want to stand on the wrong side of history.

SBLikewise, you have also talked a lot about the significance of Taiwan when it comes to the history of queerness in Asia; how might you respond to critiques that the Taipei show did not delve into this history enough?

PSI think our curator Sean C. S. Hu did a wonderful job in presenting a timeline that includes the history of LGBTQ movements in Taiwan as well as other parts of Asia, highlighting relevant artists and exhibitions preceding our show at MOCA Taipei. If we have not been as thorough or comprehensive as expected, we humbly accept such critiques and welcome any corrections or amendments.

SBDo you have plans for follow-up exhibitions for Spectrosynthesis, or do you have other projects under development? How might the current crises of pandemic and social unrest feed into those plans? I read that you were hoping to stage a project around the Gay Games, slated to take place in Hong Kong in 2022, for instance; a city where you were born, but which is enduring a prolonged period of political instability.

PSWe plan to organise another gay-themed exhibition in Hong Kong during the Gay Games because sport works in the same way as art in promoting inclusivity and tolerance. As for the prolonged period of unrest, I believe in the tenacity and resilience of Hong Kong people and a brighter future for everyone there, including the LGBTQ community.

SBIn 2018, you wrote a reflection on the year for the ArtAsiaPacific's Almanac, where you mention a number of queer exhibitions, including The Other's Gaze at the Museo del Prado in Madrid, which involved curators installing texts next to works in the museum's collection to highlight their queer aspects and histories, such as identifying a sculpture of Antinous as a representation of the Roman Emperor Hadrian's lover, or an acknowledgment of Caravaggio's sexuality. 'This, of course, truly reflects how integrated gay people are in society', you wrote. 'We're not all together, fenced into one area. We're out there, part of the community.'

What other exhibitions have been particularly meaningful and inspiring to you and your work?

PSIn 2017, Queer British Art 1861–1967 was hosted by Tate Britain to commemorate the 50th anniversary of decriminalising homosexuality in England. My colleagues and I went to London to meet with the curator Clare Barlow and learned a lot from her in various aspects of putting together a show of this scale.

In particular I remember Clare telling us that she spent a lot of time talking to LGBTQ organisations and we tried to do the same when we hosted Spectrosynthesis I & II, using my connections in the community built through many years of supporting the gay rights movement.

SBFinally, I wonder if there are any works in particular that give you comfort or strengthen your resolve when it comes to the work you do, or indeed navigating trying times, and what makes them meaningful for you? I understand you have a Keith Haring-Tseng Kwong Chi collaboration sitting above your desk, for instance...

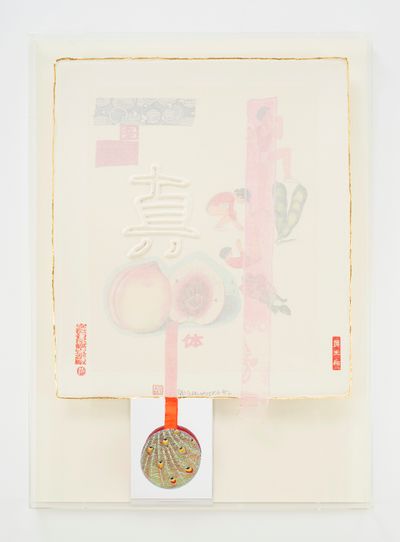

PSHanging outside my office door is a collage by Robert Rauschenberg with images of a split peach, embossed Chinese characters, an embroidery of a peacock feather, mirror, gymnasts, and so on.

Read in context of the artist's sexuality, these images are even more interesting with their queer connotations. Titled Truth (1982), it reminds me of the lies and pretences all gay people have to go through, the slanders and misunderstandings we are subject to, and how lucky some of us are to be able to stand Out and Proud.—[O]