Shahzia Sikander's Parallels of Interconnectivity

Image: Shahzia Sikander in front of her installation, Gopi Contagion, Times Square, 2015. Courtesy of Sikander Studio. Photo: Julie Holder.

Image: Shahzia Sikander in front of her installation, Gopi Contagion, Times Square, 2015. Courtesy of Sikander Studio. Photo: Julie Holder.

From being the first in a pioneering group of artists who breathed new life into the ossified tradition of Mughal-era miniature painting, Shahzia Sikander has left a trail in gouache across genres and cultures, gathering an astonishing number of accolades along the way.

Still smiling from what looked to be an exhilarating exhibit of her animation Gopi Contagion on the screens of New York's Times Square in October, Sikander spoke with Anita Dawood about her new exhibition Apparatus of Power (16 March–9 July 2016) at Asia Society Hong Kong.

Starting as an undergraduate at the National College of Arts in Lahore, where she began shifting the subject matter and composition of miniature painting into a new, contemporary context, Sikander's work has continued to experiment with dislocation. This used to be a rite of passage for any diasporic artist, but today, with a rising spiral of violence in the world accompanying the dislocation of ideas, ideologies and peoples from their social contexts, the 'unexpected juxtapositions' in Sikander's work have a particular relevance.

What does the state of hyper-connectivity that the world finds itself uneasily negotiating mean? How has history led us to this and who has the vantage point to write this history? These are some of the themes Sikander explores in her recent work through a formal visual language where, for instance, the collision of cultures and peoples resonates with animated physical encounters between ink and paper. For a society searching with increasing urgency for a context of its own, the historical gaze in Sikander's work strikes a particularly resonant note in Hong Kong.

ADWould you talk a little about the ideas behind your new work at Asia Society Hong Kong?

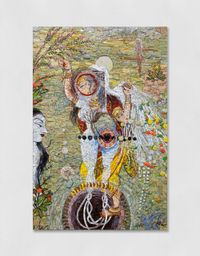

SSThe new work continues to engage the idea of inventiveness, in how a motif can communicate in multiple contexts, forms and formats. There is some investigation into the idea of myth and the notion of flight. One of the motifs introduced is Mi'raj, the physical and imaginative journey of the Prophet in the Islamic tradition, as a metaphor for the realm of imagination.

I am interested in the dislocation of objects and forms and how meaning is constantly in flux. Also the idea that a subjective realm exists within objective, physical bases and what something is 'like' becomes more than a physical attribute. It calls out the difficulty we have in accounting for our knowledge of what it is like to undergo experiences while we are undergoing them.

Early on in my practice I began developing a personal vocabulary, an alphabet of sorts, in which forms could serve as stock figures and no longer had to hold onto their original meaning. For example, the dislocated hair from the gopi figures, which interfaces in new ways in the current flight series. The gopis (female cow-herders in Hinduism, known for their devotion to the god Krishna) represent a feminine space, a multiplicity of female presence in a single frame.

Yet in Gopi Contagion, which was played on digital billboards in Times Square the month of October [2015], there is no direct reference to the female figure of the gopi other than the silhouette of her hair. The gopi-hair motif functions as a flock, reflecting the behavior of cellular forms that have reached self-organised criticality and resulting in a redistribution of both visual information and experiential memory.

ADYou have often been asked about why the miniature practice is so central to your visual vocabulary and in your response you have talked about how your practice encompasses many other influences. Could you say a little about the main influences on your work that come from outside miniature?

SSI gravitated towards miniature painting during a time when it was not popular or hip, locally or internationally, intuitively seeking a catalyst for opening new territories and dialogue. This impulse to go against the grain remains at the core of how I think and work. For me art has always been an instinct to imagine the future.

Ideas are a powerful entity and the choice of deconstructing miniature painting at a time when it was considered enslaved to craft and technique was radical.

That attitude of taking risks and listening to my instinct continues to inform me. In 1987 I started experimenting with traditional miniature painting in Pakistan by inserting the flux of the personal into a conventionally thematic space. No one had yet created a rupture from within the discipline to not only deconstruct but also dislodge it from its dominant history.

At the National College of Arts in Lahore, there was the master teacher Bashir Ahmed who had taught since 1976 and was exploring the miniature from within the thematic prism, and the conceptual painter Zahoor ul Akhlaq who was deconstructing it on canvas within the canon of Western painting.

I chose to work with traditional materials, from within the miniature painting methodology with the aim to subvert it with humour and self-critique. My thesis in Pakistan in 1987-90 and an entire body of work created in the early to mid-nineties in the US pioneered a movement which a decade later came to be known as the neo-miniature. Critical thinking, creativity and collaboration are the three tenets on which I have built my entire understanding of being an artist. Literature, biographies and historical writings influence me. I've always been an avid reader and reading is a fundamental part of the process of my work.

Derek Walcott, Gabriel García Márquez, Kafka, Susan Sontag, Qurratulain Hyder, Wisława Szymborska, Homi Bhabha, Langston Hughes and bell hooks are some of the thinkers who continue to influence ideas in my own work. I have also been deeply interested in the work of Andalusian theosophist Muhyiddin Ibn ՛Arabi. Artists whose works I have examined in different phases are Paul Klee, David Hockney, Eva Hesse, Nancy Spero, Martha Rosler, Caravaggio, Goya, Forrest Bess, Christoph Schlingensief.

ADWhat are the formal elements of the miniature that you feel have been constant in your practice, that you keep coming back to, or that took longer to get to, or were difficult to let go of?

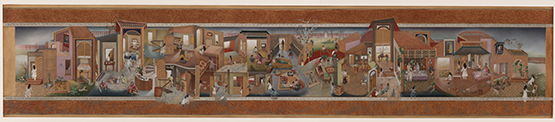

SSPsychology of color and compression of space, I'd say, I have explored consistently. If you look at my recent multi-channel work Parallax (2013), and Pivot, (2013) there is an uncanny similarity to The Scroll (1989–90). Both works were departures in terms of form and scale. The Scroll was a game changer in many ways.

Instead of depicting a contemporary version of a traditional ritual it explored the insertion of youth, the flux of identity, the narrative as a moving image and the picture plane as an infinite space. I was looking at narrative structures in film and cinema when I conceptually laid the foundation for The Scroll in the late eighties.

The departures or ruptures that happened were varied in both technique and form. By inverting the centre and margin relationships I dislocated framing devices to open up the narratives of gender and identity. Early influences were Satyajit Ray, Antonioni, Hitchcock and the film Metropolis used as a lens to explore Safavid painting's depiction of narrative, light and the mysterious interiority of space.

The Scroll had cinematic ambition in a small densely-packed space while Parallax is an entirely immersive visual and audio experience at 12 x 65 feet scale. In the way The Scroll merges multiple narratives into a single frame, Parallax employs inter-disciplinary thrust to juxtapose poetry, painting and animation to broadcast a heightened sensorial experience.

I am interested in disrupting a binary reading of any one particular event because I think it has the danger of being too simplistic and reductive.

ADYour work is often (although not always) characterised by its colour and complexity, but some years ago you did an unusual series of graphite portraits—Monks and Novices—that showed at Birmingham's Ikon Gallery in the UK in 2008. You had worked in graphite before but this series was a very different body of work—very sparse and powerful in its simplicity.

You have talked about how drawing is fundamental to your practice and I am wondering what your reflections are on that work now, and given how powerful the work was why you haven't wanted to work in that way again?

SSI don't consider the Monks and Novices series as a former way of working. The simplicity of graphite on paper was the best way to execute and represent the contemplative, focused minimalism of the subjects but if you're referring to portraiture, I've never moved on, so to speak, from portraiture. In fact, in the upcoming exhibition at the Asia Society there is a chamber dedicated to the running thread of portraiture in my practice including new graphite portraits. I continue to use portraiture as a lens to study human nature.

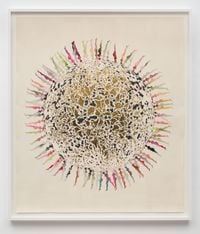

However, my use of portraiture is not literal. The approximation inherent in casting a relationship between the observed and the drawn is fascinating too. In my portraits of the heptagon for example, the variations themselves are about the fact that, as a shape, a heptagon can never be exactly reproduced. The idea about vantage point and inherent approximation is also present in storytelling versus history. Whoever gets to tell the story, often ends up owning history.

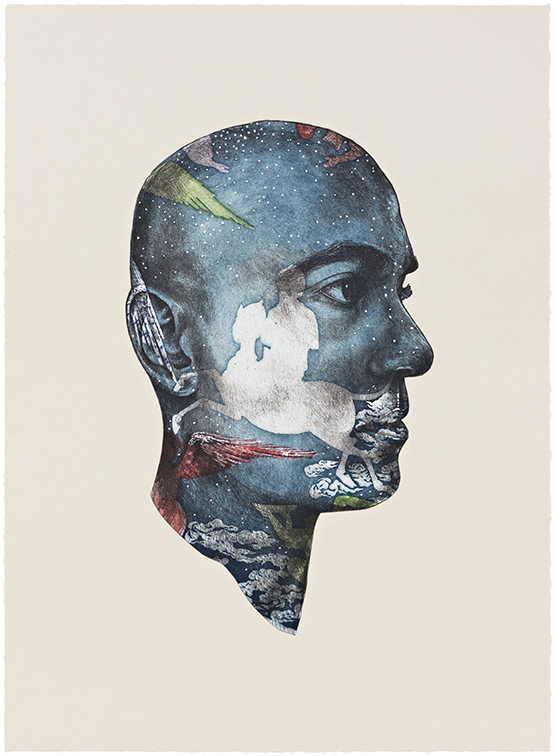

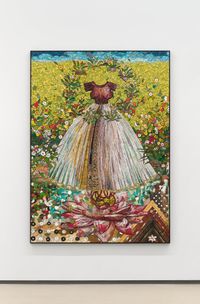

My painting The World is Yours, The World is Mine (2014), inspired by Gabriel García Márquez's style of storytelling is also a response to the events of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014. Its spread to Europe and the US introduced a narrative suggesting our unease with connectivity in a supposedly hyper-connected and globalised world.

To draw a parallel along the lines of interconnectivity, I focused on figures and portraits of Harlem Renaissance poet, Langston Hughes and hip-hop artist Nas, as two storytellers who have distinct relationships with lyric verse and who also serve to shape a collective narrative by uniting disparate elements. The painting led to a video animation, Gold Oasis (2015) with music by Nas. Both works invite viewers to reimagine historical content and entrenched symbols, and challenge and re-examine our histories.

ADYour installation work has often been in the form of building layers of visual imagery, experienced in three-dimensional space. These same ideas of visual layering are worked into your animations but in these you are more directive, drawing the viewer's attention to a particular element that you isolate and tease out, sometimes with humour.

Could you talk a little about the connections, if any, between your installation practice and your animation work?

SSThere certainly are connections between the two and both have origins in drawing. I began playing with scale simultaneously in undergrad at NCA [National College of Arts in Lahore] while learning traditional miniature painting. Early works in grid and mosaic format were ways of breaking down the form so it could be scaled up—similar to how a vector worked in later animation experiments.

In graduate school at RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] I approached the idea of the 'mural' as a 'wall drawing' or 'floor drawing'. I was intrigued by how sizing up impacted the visual vocabulary I was developing and what that could mean for miniature painting.

One can look at architecture as regional portraiture.

My 1995–97 exhibitions at the Glassell MFAH in Houston, Yerba Buena in San Francisco and The Drawing Center in SoHo were some of my first exhibitions of wall drawings in a museum. By then I was adding depth to my wall drawings beyond the two-dimensional sphere by creating ephemeral installations out of multiple sheets of translucent paper.

Layering worked as a strategy to juxtapose overlaps of culture, politics, art, history and social commentary. The intent is to transform motifs and cultivate new associations for trenchant historical symbols and this way I can service more than one vantage point. I am interested in disrupting a binary reading of any one particular event because I think it has the danger of being too simplistic and reductive. Instead, I explore how to complicate this through unexpected juxtapositions and by using interdisciplinary perspectives.

My digital work preserves the performative act of drawing on paper as well as the physical encounter between ink/gouache and paper, and layering also becomes a tool to create volume in information and content. The audio is layered in tracks and moving between various visual and sound layers allows the experience to contract and intensify.

ADArchitecture seems to be a recurring trope in your work. The Scroll, your thesis work, was set in a series of interconnected architectural spaces. So much of your practice has the appearance of being fluid and open but there are often structures, walls and other architectural elements within your compositions that can appear to constrain. Will you talk a little about this interest in architecture: where it began and how it informs your work?

SSI have been interested in architecture since I was a student. Spaces, literal and figurative, inform me. Physical structures are rife with history, especially if the design reflects a culture's aesthetic rather than the architect's; or if design elements are symbolic of something or someone, and so many buildings of a certain era are.

One can look at architecture as regional portraiture. So too, there is often unmined political lore surrounding architectural relics and because I'm interested in dissecting historical narratives, including or introducing an architectural ingredient to a composition can be a mechanism to hint at context within the overall subject.

The intent is to transform motifs and cultivate new associations for trenchant historical symbols...

ADAsia Society Hong Kong is architecturally an unusual and interesting space. Given your interest in architecture, how, if at all, has this influenced or informed what you are presenting at Asia Society Society?

SSIt is not just the architecture of the space but its history that interests me equally. Built by the British Army in the mid-nineteenth century for explosives and ammunition production and storage, the Former Explosives Magazines [Compound] at the old Victoria Barracks is among the few still existent today. Their design reflects functional practicality in that the vaulted ceiling would draw the force of an explosion vertically instead of laterally, and their thick granite walls kept the interior humid, a necessity for the ammunition.

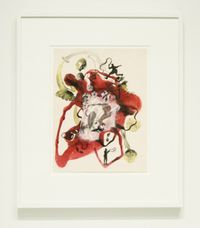

The site served as housing for British soldiers between 1843 and 1846 before it was transformed into a production and processing plant for artillery. The protagonist in my work The East India Company Man (2010), is precisely the official who would have once lived here. The Last Post (2010), deals with the history of colonial struggle and international trade in India. The animation takes as its subject an 'exploding' East India Company man, a riff on the figures of authority associated with the British trading company of the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries.

ADYour exhibition at Asia Society 'explores the colonial complexity in the region' and in particular the opium trade between Britain and China. What aspect of the region's colonial past has sparked your interest and been the starting point for your investigation into it?

SSColonial legacies and the effects of partition have been a subject matter for my work for years and the impact of the East India Company specifically has dominated recent studies of mine. Their trade strategies from the seventeenth century continue to inform today's commercial activities and some of the biggest corporate monopolies operate under some of the same entrenched mechanisms. The animation, The Last Post, specifically addresses China, the opium trade and the exploitative means by which demand for the commodity was established. The title of the work refers to the English bugle call.

Commemorating the soldiers who die in war, it also signals a call for the end of the day. Here it refers to the collapse of the Anglo-Saxon hegemony over China. The protagonist, an East India Company man, appears in various guises throughout the piece often as a lurking threat in the imperial rooms of the Mughal Empire, which once ruled much of South Asia. The Company man was also a visible figure in China during the Opium Wars of the nineteenth century.

Historically, the movement of objects such as in trade and colonial occupation allows their meaning to shift as they enter different contexts. In that respect issues around identity are constantly evolving. The Strait of Hormuz and Hong Kong are similar in that they were both entrepôts and centres for maritime activity for the British East India Company at pivotal points in its history.

Parallax, examines mechanisms of power and ideas of conflict and tension over the control of strategically desired geography, a place where one-fifth of the world's total oil passes. Historical events that create tumult in colonial territories, naval warfare, the East India Company, imperial air and land travel routes and maritime trade all underlie the work. —[O]