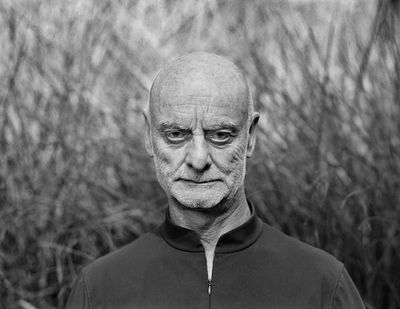

Dr Uli Sigg

Image courtesy of Dr Uli Sigg.

Image courtesy of Dr Uli Sigg.

When Sydney art dealer Ray Hughes visited Swiss collector Uli Sigg at his Mauensee residence near Lucerne some years ago, a mutual friend asked the dealer how the visit went. 'Did you feel comfortable and find a place to kick your feet up and read?' 'No, to both,' answered Hughes, 'it seems there was only art everywhere.'

Sigg has enjoyed a distinguished career—first as a businessman in China with the Schindler Group to create what would become the first joint venture with the Chinese government; then as Swiss ambassador to Beijing in the mid-eighties. But it is art that has defined Sigg's life more than anything else.

Over a period of four decades, Sigg managed to put together one of the world's most impressive and encyclopaedic collections of contemporary Chinese art. Comprising over 2,200 works by some 350 artists, it is considered to be the world's largest collection of contemporary Chinese art to date. His consuming passion and drive for Chinese art has made him one of the most renowned figures in the contemporary art world, to say nothing of the Chinese contemporary art world. 'My China stories are in the art works', Sigg once stated. And indeed they are. In fact, one may argue that within the collection is the history of modern China.

I was in China as a businessman and diplomat so I saw very different realities, and contemporary art was just another access for me, but I always thought about how to integrate it into the full Chinese picture. So, I was always able to contextualise the work, not just within art, but also in Chinese society and all of this. Which was very important for me, personally.

Sigg is the antithesis of the loud, brash, show-me-the-money insta-flipper collector that has sadly come to influence the art market these days. For him, the art is everything. The collector, as Sigg would insist, is nothing. The 69 year-old collector has been engaged with and heavily invested in Chinese art and culture since his first business trip there in 1979. He witnessed first-hand the development of Chinese contemporary art—from repressed underground experimentalism to heady global art market domination—in tandem with the country's social and political changes. And he played a crucial role in bringing Chinese artists to the West. In 1997, Sigg established the Contemporary Chinese Art Award, a biennial competition that launched the careers of several Chinese artists and brought international curatorial exposure to the Chinese contemporary art scene. It's not for nothing that he's earned the moniker 'ambassador of Chinese art'.

In 2012 Sigg donated the bulk of his collection to Hong Kong's M+ museum of visual culture, where he serves on the acquisition committee. His 1,510-piece donation, valued at the time at HK$1.3 billion, was one of the most significant made to a museum in recent years. It certainly marked a turning point for M+ and also for Hong Kong's bid to be a cultural capital. Now exhibiting in Hong Kong, M+ Sigg Collection: Four Decades of Chinese Contemporary Art gives the Hong Kong public its first glimpse into the collection that will form the backbone of the museum's permanent collection.

M+ Sigg Collection: Four Decades of Chinese Contemporary Art is surprisingly the first to narrate one of the most remarkable events in the last 100 years of art history in a concentrated, chronological, and hopefully crystallised way', states former M+ Executive Director, Lars Nittve in the foreword to the catalogue for the exhibition. Comprised of selected highlights from the Sigg collection, the exhibition features 80 pieces (paintings, installations, photography and video works) by 50 artists (including Zeng Fanzhi, Wang Keping, Song Dong, Ai Weiwei and Zhang Peili) presented in chronological order across four decades of Chinese history.

Grouped into three periods—1974-1989, 1990-1999 and 2000-2012—the show reflects on the development of China's art scene and the relationship between art, society and politics. Each period addresses major milestones in modern Chinese history: the end of the Cultural Revolution, with small works by Zhang Wei painted in secret; the Tiananmen crackdown, with photographs by Liu Heung Shing depicting the bloody aftermath; and China's sprint towards globalisation and economic power in the 1990s and 2000s for which a new generation of artists, like Cao Fei and Yangjiang Group attempt to address the environmental and social impact.

The M+ Sigg Collection was previously presented at the Bildmuseet at Umea University in Sweden in 2014 and at the Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester in 2015. As well as the Hong Kong exhibition, portions of Sigg's M+ collection will be on display as a joint exhibition by Kunstmuseum Bern and Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland. Added to this is a film on Sigg's collection, which has just screened in Bern and will soon be screened at Hong Kong's Art Basel. It looks like the spotlight has found and indeed made a star of this unassuming and softly spoken champion of Chinese contemporary art.

I caught up with Sigg on the eve of the Hong Kong exhibition to discuss his experiences as the world's pre-eminent collector of Chinese contemporary art, and the latest M+ exhibition.

At first I was looking with a Western eye: I was looking for art that could contribute to the global artistic discourse. But of course that is what I couldn't find. Only when I decided to take a more documentation approach—a collection which allows you to read the story of Chinese contemporary art, because nobody had been doing this—only then did I start looking for works which were very important to Chinese art history. So that's really the difference. I had to change the focus to whatever was important for Chinese art history.

DAHow did you start collecting Chinese contemporary art? When you first started looking at Chinese art there weren't any galleries in China, and certainly no Chinese art market.

USI started in 1979 when I was first there with Schindler, but I wasn't really excited with what I saw at the time. I looked at a lot of work, but I didn't collect it. But then by the late eighties I started to look at it a little deeper. I felt that art had found its own language. It wasn't until the nineties that I really started collecting. By then I moved around China very freely. I moved everywhere, even though a lot of art was semi-underground. The constraints were not like the eighties where I was always observed and followed. In the nineties I could just get in my car and travel where I wanted to different artists' studios.

DAThe earliest works in the exhibition, paintings by Zhang Wei who was part of the underground 'No Name Group', date back to 1974 and 1975, post-Cultural Revolution. There was a great deal of artistic repression then and art was being made underground. Were you aware of the political and social significance of the works you were picking up then?

USYes. I'm a researcher by nature, and I was fortunate enough to buy the results of my research. Of course, maybe that's the difference to the people who move exclusively in the art world. I was in China as a businessman and diplomat so I saw very different realities, and contemporary art was just another access for me, but I always thought about how to integrate it into the full Chinese picture. So, I was always able to contextualise the work, not just within art, but also in Chinese society and all of this. Which was very important for me, personally.

DAYou came from a very Western-centric discourse and understanding of art before moving to China. How did you initially view Chinese art? Did you have specific criteria in mind when you started collecting art or did this evolve with time?

USWell, in the earlier years—and you also see it in the collection—I found a lot of the art derivative of Western art, because it was the first time artists could do autonomous art. They could decide what to do, they could leave the language of socialist realism, so they experimented with the little information they had about Western art. So, for us it looked very boring. It took quite some time until a language appeared that was not derivative. And at first I was looking with a Western eye: I was looking for art that could contribute to the global artistic discourse. But of course that is what I couldn't find.

Everything was 50 years too late, 70 years too late. Only when I decided to take a more documentation approach—a collection which allows you to read the story of Chinese contemporary art, because nobody had been doing this—only then did I start looking for works which were very important to Chinese art history. But they didn't have to contribute to this global art discourse at the forefront of Western art.

So, that became a very different focus, and that had me collect very different things. I was collecting backwards, like the No Name Group. It made more sense. But before, if you were looking for the forefront of contemporary art, all this was not of much relevance. So that's really the difference.

I had to change the focus to whatever was important for Chinese art history. Of course ideally it would also contribute to the history of global art discourse, and there are many works that do, but there are also many works that don't.

DAWhat difference do you see between the pre '89 artists to today's new generation of artists?

USWell now of course artists have fully caught up. Where once there was a time lag, of course they have now mastered all media, they have no issues with techniques and have access to information. And this is all reflected in the art. And some of it, as we discussed earlier, comes across like this global mainstream.

And tradition, or dealing with tradition has gained a lot of weight. In the 'eighties nobody would ever want to hear about tradition—it was all about Western conceptualism—whereas now a lot of artists are disillusioned with this Western conceptualism. That's a trend emerging from the last few years. Very diverse directions and strands and all media.

I'd much rather have a whole institution decide how to deal with the collection, rather than just me myself. And there's also a question of means. I have decided I'd rather put my resources into collecting than building this great monument to myself.

DAIs there a particular memorable anecdote or encounter with an artist that springs to mind about any of the works in the exhibition?

USThere are a million moments, but there's this work in the exhibition by Ai Weiwei—an installation with 4,000 axes [Still Life]. I wanted to offer Weiwei more money than he actually wanted. He wanted a really ridiculously low price. I felt it should have been much higher, and he said to me, 'It doesn't really matter if you or I own it. That's irrelevant and just a blip. These axes have been here for 10,000 years, so what's the human life span? What does it matter who owns it? You take it.' So I did and now I have passed it on to M+. I also don't matter. It was an interesting way of thinking about art and its long-term relevance, if it ever has one.

DAPrivate museums are sprouting up all across China. Given your world-class art collection, why did you forego the private museum route?

USA number of reasons. But mainly, I'm very much a fan of the public institution. I think only the public institution can provide the long-term guarantee that it will continue to exist and it will be 'the' public memory. I have seen a number of private museums come and go in China. Maybe the owner goes bankrupt, maybe the owner decides to hang around with film people, not the art people, so then the money goes there. And you are hostage to the taste of the one person. Maybe that's the main issue. I'd much rather have a whole institution decide how to deal with the collection, rather than just me myself. And there's also a question of means. I have decided I'd rather put my resources into collecting than building this great monument to myself. I'm not so important in this. The collection is much bigger than me.

Of course I built it and there are traces of me in that collection, but it is much bigger than I am. I think it's an important document to the Chinese culture, whereas I personally am not.

DAIs the show travelling to other cities?

USI think M+ is negotiating to take the show to Japan, Korea. It will travel in Asia.

DAThere is also another exhibition taking place simultaneously in Bern.

USYes, but the Hong Kong collection is more chronological while the Bern exhibition is an overview of the collection in the last ten years. In Bern it's a much more recent and younger exhibition, going back only to 2005.

People must go to Bern. It's a really good exhibition. It just opened with 800 people coming to the opening.

DADid you ever encounter resistance or find it problematic being a foreigner championing contemporary Chinese art?

USIt was an issue early on when I created the Contemporary Chinese Art Award in the very early stages in 1997. There was a debate that I, as a foreigner, shouldn't be able to decide what's meaningful art or less meaningful art in China—because there was no art award then. This was the first one and I did it to create a more domestic discourse and to bring in important foreign curators [such as Swiss curator Harald Szeemann who went on to include 20 Chinese artists in the 1999 Venice Biennale] so they would see Chinese contemporary art, because at that time nobody had a clue about Chinese contemporary art.

That's hard to imagine today. But that was a debate then. I had to explain myself, why I did this and why I should have a say in this—not the only say, but a say, because I had seen more of China than most Chinese back then ever could. In the eighties and nineties people couldn't travel freely around.

I had to go around everywhere, but they couldn't. And I had seen and met with thousands of Chinese artists, many hadn't. So I did this award to collect a lot of material at the time when there were no books, no catalogues, no internet. So I saw more material than almost everyone I know. I had to explain all this so everyone would understand. So yes, there was a moment where it was a problem, whereas today nobody disputes this. —[O]

M+ Sigg Collection: Four Decades of Chinese Contemporary Art

23 February to 5 April, 2016

ArtisTree, 1/F Cornwall House, Taikoo Place, 979 King's Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong