Xinyi Cheng and Alvin Li: On Intimacy and Waiting

In Partnership with Asymmetry Art Foundation

Xinyi Cheng. Photo: Shuwei Liu.

Xinyi Cheng. Photo: Shuwei Liu.

Paris-based painter Xinyi Cheng has come a long way since her early training in China's art academies, where Social Realism presided as the dominant mode. Cheng's atmospheric portraitures today actively look beyond the confines of reality, setting fictionalised sitters within atemporal spaces.

While initially trained as a sculptor, Cheng's interest in painting can be traced back to a young age. The artist recalls visiting Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris as a child and being taken by the Impressionist galleries, and particularly Monet's paintings, which inspired landscapes rendered in plein air. But after being discouraged by professors who urged for a more distinct visual language, she set aside naturalism, too.

Cheng enrolled at the Maryland Institute of Art, Baltimore, where she learned to incorporate minimalism and abstraction into her careful portraitures, which similarly reduce their compositions into elementary juxtapositions of backdrop and figure. 'I wanted to reject my past by not making anything look realistic,' Cheng says.

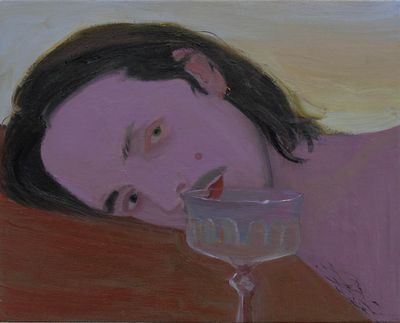

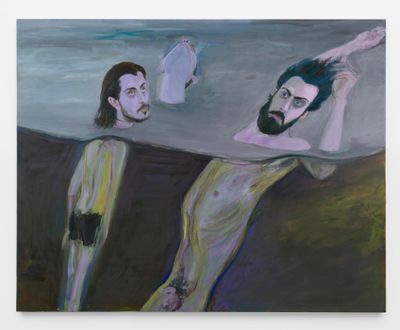

Photographed first, then re-imagined on canvas, Cheng's cast of friends and acquaintances are placed within atmospheric compositions overseen by a presiding stillness that lends each painting a surreal edge.

Set against soft grounds, young male subjects have become the focal point of Cheng's work since moving to Paris in 2017. Often nude or intimate, but left open to interpretation, they extend a fiction that earned the artist the 2019 Baloise Art Prize.

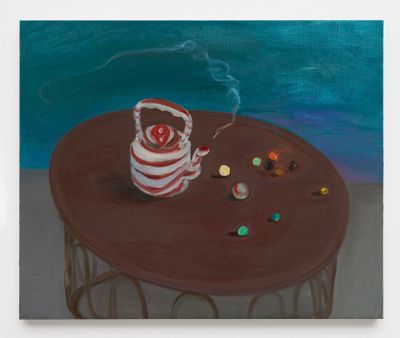

A survey of these works featured at Lafayette Anticipations, Paris, for Seen Through Others (2022–2023), Cheng's largest exhibition in France. Nocturnal scenes and domestic interiors populated by human and animal figures appeared as subconscious reflections of the psyche. In a muddy yellow room, a young man in leopard-print boxers is immersed in a phone call on a leather sofa (Landline, 2021). Midnight falls as two horses swim neck-deep in water (Swimmers, 2021).

In the following interview Cheng speaks with writer and curator Alvin Li, elaborating on her trajectory from Social Realism to atmospheric portraitures that abstract their environments, distinctions between the public and private, and how fiction helped her move away from realism.

The text is a transcribed and edited version of a talk between Cheng and Li which took place at The Courtauld Institute of Art in London earlier this year. It was the first in a lecture series initiated by Asymmetry Art Foundation, which invited dialogue between writers, curators, and artists from the Chinese-speaking community, and concluded with a symposium in May 2023.

Asymmetry was founded by art collector and patron Yan Du for the purpose of supporting Chinese-identifying curators. In addition to the lecture series, the foundation provides placements, research fellowships, and postdoctoral funding in partnership with organisations such as the Courtauld, as well as other leading arts organisations such as Delfina Foundation, Whitechapel Gallery, Chisenhale Gallery, and Goldsmiths, University of London. Other initiatives include art publishing projects, a library residency, and plans to initiate exchanges with institutions in mainland China.

ALXinyi, you dabble with sculpture and photography, but overall, you consider yourself a painter. Would you agree?

XCYeah. Yesterday when I was crossing the border from France to the U.K., the customs officer asked me what I do and I told him I'm an artist. He asked, 'What kind of art?' I said I'm a figurative painter. And he asked if he could see my work. But I actually studied sculpture in college.

ALIn Beijing, right?

XCYes, at Tsinghua University's Academy of Arts and Design. I also did the required training before going to a Chinese art academy. When I was in high school, I spent three years drawing and painting life models, and then four years in college sculpting life models. But I don't do these anymore.

ALSo when you moved to MICA, you left sculpture behind and really got into painting?

XCI was already painting on the side. My parents took me to Paris when I was 12, we visited the Musée Marmottan Monet, where there is a huge collection of Impressionist paintings and I fell in love with Monet. My college training is in Social Realist vein, but I considered myself an Impressionist painter on the side. I was quite serious about it, but I didn't really find my voice.

In my third year of college, I brought my landscape paintings to a professor and asked for advice. He said, 'They are nice, but 95 percent of our students can paint like that. So, what's your point?' I was heartbroken. I didn't want to paint landscapes or in plein air again. I thought I needed to get out there, so I applied to grad school in the U.S. I knew I wanted to split from both Social Realism and Impressionism.

ALWhat were you exposed to at MICA? What are some early experiments you undertook?

XCWhen I arrived in the U.S., I didn't know much about contemporary painting. I knew about Lucian Freud from my training in China because he was considered the greatest figurative painter of the century.

At MICA, I got into the multidisciplinary programme, where I studied with sculptors, video artists, and conceptual artists. There is a painting programme, where most artists paint in the abstract style. Through them, I learned about painters like Agnes Martin, Frank Stella, and Josef Albers.

ALYou said no to realism but stuck with figuration. Could you say more about that?

XCI am interested in people, and it didn't take me long to realise that I still need to paint them. I see figuration as a vessel to paint emotions. I tried to be an abstract painter; I did one or two paintings, but I don't know how to do it, so I stuck with figurative painting.

At the time, my teacher Frances Barth introduced me to interesting American modernists like John Graham, Marsden Hartley, and Bob Thompson. I wanted to have fewer figures and draw their outlines, so they can become abstract shapes. I wanted to reject my past by not making anything look realistic; through not painting shadows, not having volume in the figures, and doing everything through colour and shapes.

ALDid your peers and professors encourage you in this direction? I believe in the early 2010s, and even now, there was an insistence on dealing with one's Chinese background or Chineseness.

XCI feel like in school, you always have to justify yourself. I did feel pressure and tried to come out with something to say. At the same time, I didn't want to make a painting with a five-minute introduction that gives a background on what I am making.

For me, displacement means creative freedom, like being able to be somewhere else, to be able to transcend something.

First, I didn't feel like I had anything insightful to say about China at that time. Second, I believe the work must speak for itself. I didn't want to worry about it. As a figurative painter in a graduate programme, I found it hard to deal with the judgement, 'your painting looks decorative'.

ALYour paintings now have a really focused subject matter: people and things you encounter in everyday life, which you then cast in fantasy scenarios. Could you speak more about your working process as you've matured and the relationship between photography and your paintings?

XCI take a lot of photos as references; I don't want to paint from life ever again and I don't have a photographic memory. I then make drawings based on the photos to reduce elements. Everything in the drawing is what I'm excited to paint. It's like collages in my mind.

ALI'm interested in what you just said about reduction. Was it a response to the comment about being decorative?

XCYeah. I felt like fighting against that kind of comment required my making more precise decisions in the paintings. For everything I paint, I need to know exactly how it's going to function and that everything feels necessary in the image.

ALWhat is your relationship to your subjects? You said you don't really have models at your studio, you just take photos. And most figures are friends or people you know well.

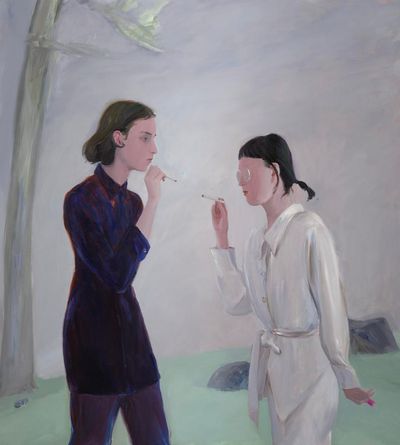

XCYes, I paint people I know. Sometimes, I have a situation in mind that I want to paint, and then I invite people to my studio and ask them to enact the situation. I capture them drinking and smoking cigarettes. Then, I make drawings based on the photographs.

ALAre there elements from your training in realism that have remained?

XCI think it made me more confident. Painting a good face and hand is very hard. I kind of labour and spend a lot of time trying to figure out how. At times it looked ugly, but I had the confidence that I could figure it out, so all those years painting life models helped in some way.

ALYou've established your relationship to the figures you paint—not models, but characters that you cast and subject to a process of fabrication. Would you agree with this description?

XCThe people I paint play a role in the painting. They are characters.

ALMost of the scenes you paint are quite intimate; they're between lovers or close-up shots of kissing and touching. I think you paint with the understanding that these intimate moments will be exhibited in public. Do you take pleasure in this public display of intimacy?

XCI think it remains intimate. When I started to make some of these paintings, I didn't have a lot of shows. The people I painted were people I hung out with. They came to my studio to see the painting. I feel like that was intimate, for sure. Then I got opportunities to show at galleries and museums. I had this question for myself: if intimate paintings are shown in a public space does the intimacy remain?

Then I went to see the Edward Hopper show at the Whitney Museum on a busy day. I put my headphones on and walked through the galleries. When I saw the physical painting, I still felt a connection. It was still a one-on-one relationship.

But when the image of the painting is posted on Instagram and spreads on social media, then the relationship changes and gets complicated. Because when you see a painting, your reaction to the painting is very physical, which doesn't translate to digital media.

ALI'm interested in how your working relationships with your characters, who are close friends, almost become a microcosm of your understanding of the social. This feeling of intimacy can be very fragile, and the slightest infringement can feel like a betrayal or violation. Why do you choose this way of collaboration?

XCFirst, I adore and admire the people I paint. I know they are very kind people, very beautiful, and so they are not boring for me. I feel like knowing them gives me so many ingredients and feelings. But now that I've made these paintings, I feel like I made a representation of them. I'm grateful that they trust me and let me do things with their image. I want to create situations and turn them into very rich characters.

When I was in Baltimore, I wanted to say goodbye to everything I had learned, so it felt like I was learning a new language.

Alvin, you've written an essay for my catalogue and a feature on me for Interview Magazine. Those features are also portraits and your interpretations of me. I felt like, in some way, it was okay. But you also write erotic stories. Your characters are more real than mine, with real names, places, and feelings.

ALI cannot resist this kind of public display of extremely private intimacy. It can be ruthless in that sense. One of my favourite writers said writing is a predatory activity: you always use what's immediate to you. But it's really about the line between friendship and artistic freedom. When you pass judgement that you know will break a friendship, do you still do it for artistic integrity?

XCIt's so hard. What do you think?

ALAs you've read my story, you know I always pass judgement on characters because it helps form the subject. But your relationship with characters comes from a place of admiration and trust.

XCI think so. I want to take care of my characters. My goal is not to make charming, good-looking figures in my paintings but I make sure they don't look bad. I want them to be interesting and rich.

ALIn your earlier work, you almost exclusively painted male subjects, which can be read as an attempt to investigate power dynamics or avert the male gaze. Would you agree with this description?

XCI don't feel comfortable saying I paint from a female gaze. It's hard for me to understand what that means. I loved some of Courbet's paintings from the 1860s, which are very magical. I don't want to take the opposite of that perspective or paint masculinity as a general idea. I feel like there is a wide spectrum of what it means to be male. That's also why I got into painting characters.

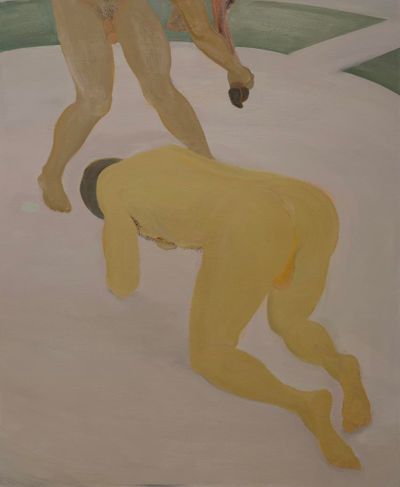

For instance, I made Fremdschämen in 2016. According to my German roommate, it means you feel embarrassed on someone else's behalf. The painting was inspired by a Spanish movie from the 1990s called Jamón Jamón. In it, two guys—one of them played by Javier Bardem—get into a fight over a girl.

One guy gets really injured; he kneels and dies. I found that very violent, masculine, and absurd. I wanted to paint this exact moment, but didn't have a personal relationship with the characters, so I asked people to model for me. I happened to observe the testicles sagging and wanted to paint that.

ALYou've recently started painting female subjects as well as other life forms such as dogs. I know that every choice you make on your canvas is so precise. Can you speak more about this decision?

XCI wanted to paint female figures for a long time, but I couldn't find an entry point. The technical development was really important. When I was in Baltimore, I wanted to say goodbye to everything I had learned, so it felt like I was learning a new language. I didn't know how to paint a face, so I avoided it. Then I learned. I also learned to paint the body, but I didn't know how to paint clothes, so everybody was naked.

When I was working on For A Light II (2020), I went to the Louvre and got a close look at this beautiful Watteau painting. I loved how bright and alive the fabric felt, so I taught myself this painting language.

Back when I didn't know how to paint clothes, I didn't want to paint a female figure as she would have to be naked. I wondered if it was possible to make a non-sexualised female nude. I didn't know how, so I didn't do it. Now that I can paint clothes, I feel like my vocabulary has grown and I can paint subtle emotions.

ALThere was a female nude in your most recent show at Matthew Marks Gallery in New York City.

XCYes. I recently painted a female nude inspired by The Origin of the World (1866) by Courbet at Musée d'Orsay. In my painting, I wanted to include the face rather than the genitalia, but also to paint a figure that is asexual. Painting a compelling female nude that is not sexualised was a struggle.

To have something exciting going on, I distorted the hand in the foreground. I've always loved Georgia O'Keeffe's landscape paintings in which she paints the mountains and bushes like a body, and I felt like maybe I could paint a body like a landscape. Well, just the pubic hair area.

ALYour motifs really matured and developed in tandem with major social-political changes in recent years such as the #MeToo movement and the recent pandemic. Minor feelings and private matters really came into public purview. Have these shifts informed the choices you make in your work?

XCCovid-19 really changed how I work. I used to make paintings about social situations: people smoking, drinking, flirting, and getting close to each other, but when everybody wears a mask for two years, it's impossible to make anybody look interesting, in my opinion.

So I made paintings of animals and lone figures. For the first time, I wanted to make paintings about existential crises or the abstract idea of disappearance. In Whirlpool (2022), I wanted to make this person disappear in the whirlpool and make it look cosmic. So yes, the pandemic really changed how I work.

ALXinyi, you've lived in America, and have been in Europe for a while. On the topic of location and displacement, whether personal or on the level of your practice, what can you share with us?

XCI made a decision to move to Paris. I'm very happy to be there because the city is beautiful. This aesthetic is important to me because, personally, I can't imagine working in the Social Realism aesthetic anymore. In Paris, I can also look at great art at the Louvre and Musée d'Orsay.

ALThe catalogue essay I wrote for your solo show Seen through Others at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris looked at the theme of waiting in your paintings, and how the characters embody a state of idleness. You make this idleness seem okay, like they are at play. They are smoking cigarettes and waiting for nothing, in many cases.

While I was writing, Xinyi, you pointed out that more than a state of being idle, it's a state of being displaced. Could you speak to this idea of displacement? Is there a degree of self-reference?

XCI feel like the displacement in the painting is me working against being naturalistic and realistic. I don't want to have a defined space and spend most of the time working on the background. I look for a certain texture or colour that I feel is right. For me, displacement means creative freedom, like being able to be somewhere else, to be able to transcend something.

ALWe return to your rejection of realism and your pursuit of the creative in how and what you paint. Could you share some of your influences? I know Roland Barth's A Lover's Discourse [1977] is huge for you. In recent paintings, you reference Lu Xun's writings as well.

XCI made a painting on Lu Xun's Old Tales Retold, which he wrote in the 1920s. There was one story called 'Forging the Swords', which was really compelling to me. Because it's an old tale—unrealistic and mythological—it gave him the freedom to reflect on social and political events. I found that to be very inspiring.

ALAre you working on anything that takes up this aspect of myth-making?

XCYes, but I've had problems telling stories in my painting because I'm afraid of being illustrative. In the last two years, I feel like I broke free from this fear. What matters is how you tell the story. You can tell it with a lot of passion, so I am interested in working with allegories of old tales in the future. —[O]