Hrair Sarkissian Redirects the Photographer's Gaze

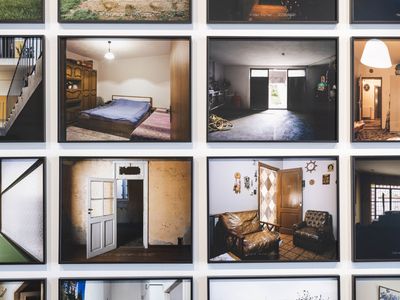

Hrair Sarkissian (2010) (detail). From the series 'My Father & I' (2010). 14 archival inkjet prints; 7 images: 20 x 30 cm each, 7 images: 28 x 35 cm each. Courtesy the artist.

Hrair Sarkissian (2010) (detail). From the series 'My Father & I' (2010). 14 archival inkjet prints; 7 images: 20 x 30 cm each, 7 images: 28 x 35 cm each. Courtesy the artist.

Hrair Sarkissian's first mid-career survey is travelling. The Other Side of Silence (30 October 2021–30 January 2022) opened at Sharjah Art Foundation featuring analogue photography, video installations, and sculptures produced over the past 15 years.

Recently shown at Stockholm's Bonniers Konsthall (27 April–19 June 2022) and headed to Bonnefanten in Maastricht (29 November 2022–14 May 2023), the exhibition includes Sarkissian's first sound piece, Deathscape (2021).

The exhibition title reflects the Syrian-Armenian artist's multi-layered approach to the image. His empty interiors and desolate landscapes, in which the human figure is often missing, are quiet encounters embedded with collective trauma and the unspeakable.

Harbouring a tenuous beauty beneath which hard socio-political realities lurk, his work alludes to histories that have been silenced: the Armenian genocide, ethnic cleansing, and forced disappearances in different parts of the world.

In Sarkissian's images, which are shot with a large-format camera, the artist captures the ravages of time and a peculiar duality between surface and content, the visible and hidden, and individual and collective grief.

Armenia, where Sarkissian's family is from, is evoked under a blanket of snow in his earliest work, 'In Between' (2006). Its landscapes return in his latest project Sweet and Sour (2022), a new commission by Bonnefanten.

Featuring his ancestral village Khantsorig in the Sasoun region (present-day Turkey), a place of legends and revolutionary myths, the project includes footage of Sarkissian's father upon seeing footage of Khantsorig, to which he has never been.

This is not the first time Sarkissian has collaborated with his father, Vartan Sarkissian, but it does redirect the gaze of the photographer as subject. In 'My Father and I' (2010), Sarkissian asked his father to take portraits of him for their last photoshoot at the Sarkissian Photo Center.

Formerly called Dream Color, it was first colour-photo lab established by Vartan in Syria in 1979, and where Sarkissian learned photography when he was young. The work includes Vartan's own black-and-white self-portraits from when he was a teenager. Documenting the end of an era, it traces a lineage of photography from the past to the present, from father to son.

The durational aspect of Sarkissian's work stands opposed to the seeming thoughtlessness of our click-happy digital age. 'Last Seen' (2018–2021), a new commission by Sharjah Art Foundation, references the online world while forming a counter-narrative.

As Sarkissian's most ambitious project to date, it comprises a composite of 50 photographs of the homes of families in Argentina, Bosnia, Brazil, Kosovo, and Lebanon, whose loved ones disappeared during times of conflict.

Sarkissian worked with NGOs in each country to locate the aggrieved families. Each photograph represents where their loved ones were last seen, laden with material culture, memory, and loss.

In a single shot, Sarkissian excavates the burdens of history and war, summoning a sense of presence in absence. Emblematic of latency, his work can be read as an act against all forms of cultural erasure. The artist elaborates on the influences behind his work in the following conversation.

NKThe Other Side of Silence gathers so much of your work in one place. How does one select work spanning 15 years?

HSWe chose works that relate to each other somehow. Directly or indirectly, they are addressing similar issues.

NKThere is a fascination with place throughout your work, although people are largely absent. In 'Transparencies' (2012), which depicts abandoned construction projects in Amman, you treat the architecture like a human body. Could you elaborate on this decision?

HSI wanted to reflect on this aspect of being alone. The images look like they were taken on a different planet—they lend the effect of a placelessness that becomes visible.

NKIn contrast to the textured states of disrepair in 'Unfinished' (2006), which also depicts incomplete, forsaken buildings in Amman, 'Transparencies' are presented as ghostly, skeletal X-rays. What led to these aesthetic choices?

HSI have always been fascinated by abandoned construction sites, where there is a feeling of fear and solitude. In that respect, both 'Transparencies' and 'Unfinished' are empty and incomplete buildings.

But they also tell different stories, which is reflected in how they are presented. In 'Unfinished', I photographed details of unfinished buildings that transcend their locality. I wanted to move away from the Western eye of photographing buildings in this region that are obviously 'oriental'.

In 'Transparencies', the buildings are a failed housing project, abandoned when the global financial crisis hit. There is a background of corruption, both actual and ideological.

If there is someone standing in the image, it distracts from my message. The absence of humans can become telling.

The skeletal black-and-white presentation as negative images in lightboxes are like X-rays—you can see through them. It also makes them timeless; they remind me of the glass prints they made early in the history of photography.

NKThere is a similar sense of inaccessibility in your earliest work, 'In Between'. You mentioned that this series is a post-Soviet view of Yerevan blanketed in snow, which prevents us from seeing the reality. Can you say more about what this reality is for you today?

HSDiasporic Armenians grow up with an image of the motherland as this mythical and aspirational place, but the reality of post-Soviet Armenia is, as you say, very different.

I photographed 'In Between' when I first visited Armenia as an adult and realised how the country was collapsing, and people were suffering. The snow gives it this shiny and white gloss, but underneath, life is not as we have always imagined it. Unfortunately, I don't believe much has changed today.

NKWhy did you decide to create an image of unidentifiable places in complete stillness and without people?

HSIf there is someone standing in the image, it distracts from my message. The absence of humans can become telling.

NK'Execution Squares' (2008) marks the beginning of your relationship with the Sharjah Art Foundation, becoming part of the collection in 2009, after it was shown at the Istanbul Biennial the same year. What sparked this series about public hangings in Syria?

HSA memory that will always stay with me. I was on the school bus, it was around seven in the morning, and from the bus, I saw three people hanging at Maysat Square, near my parents' house. Their eyes were open and we made eye contact.

NKHow did you take the pictures?

HSThe hangings usually take place at dawn when few people are around, but the bodies are left hanging for a while. I took photographs of the squares in Latakia, Aleppo, and Damascus around the same time the hangings took place.

NKWas this part of healing the trauma?

HSI am not sure it did. At first, I tried to use photography to prove that there were no bodies there. But every time I pass the square, I still see them. I failed to erase them. When you see the empty 'Execution Squares', you start to look for the bodies.

NKTo what extent do you feel that places can embody violence, especially since so much of your work is about the impact of violence that is hidden?

HSOnce viewers become aware of the invisible elements behind my work, the physicality of the image is almost destroyed. The architecture and surroundings of the squares are no more than a backdrop once you see the bodies hanging in your mind.

NKIs this where photography fails?

HSI think this is where photography actually succeeds in showing how events can be memorialised in the physicality of a space.

NKThe architectures of loss are a common thread in your work, for example in 'Last Seen', which carries so much emptiness. It could be argued that the impact of wars never really ends. In a similar vein, is your work really finished when you complete a series?

HSWhen I finish a project, I never return to it. I usually work in series to shift the focus from individual stories to broader historical impact.

NKHow do you work on the photograph to reflect the residues of a former presence, such as the person who disappears, neither dead nor alive, who is part of the domestic space of the family that awaits them?

HSI don't 'work' on the photograph. For 'Last Seen', I sat with each family for a long time, listening to their story. But in the end, I took only one photograph of the place where they last saw their loved one. The pain is the same from every angle.

NKA lot of your work is about the relationship of personal pain to macro-structures of power and violence—factors outside an individual's control. And it's as if this suspension of agency, this lack of resolution, manifests in the image.

HSI purposely don't give long explanatory texts of individual stories, I want to concentrate on the tragedy of the families' suspended grief. The only story I can give is the overarching, ongoing pain shared by families from different parts of the world.

I try to engage viewers behind the surface of what is visible, to re-evaluate larger historical and social narratives.

Although I wanted to know the history of how these mass kidnappings happened, for me, it was more significant that these families are still living in the house where their family members lived before they were kidnapped. They still want to know if that person is dead or alive. They want resolution. Life for them has stopped the moment their loved ones disappeared. They didn't move on and still live in that moment.

It was important to show how strong these women are. During the civil war in Lebanon, one woman's son said that he was going out for 15 minutes. He never came back. Her second son was hit by a mortar missile on the balcony. He was nine years old. The third son died in the basement of the shelter because of asthma. And she still smiles.

I don't have hope, nor did I experience her life difficulties. In Bosnia, they also found the remains of a woman's husband in different locations, but they didn't find his ankle. She is still not convinced he is dead. She wants to find his ankle.

NKIn contrast, 'Last Scene' (2016) depicts a certain serenity, featuring the locations that terminally ill patients in the Netherlands wanted to see before they passed away. How did this project come about?

HSI read about Stichting Ambulance Wens, a foundation in the Netherlands that provides terminally ill patients with transportation and medical volunteers to go see a place they've wanted to see for the last time. It made me question what I would like to see.

NKThere's a performative element in your carrying out this wish a year or two after each patient's visit and at the precise location where they stood. Why did you do this later in time and what did you feel?

HSI took the photographs on the same day and time as the actual visits took place. I wanted to photograph as closely as possible what they saw; it was therefore always one or two years after. I never felt that it was performative, but I can see how it can be interpreted that way.

NKCan you say more about the process of taking the picture?

HSI work with a large-format analogue camera—the process doesn't lend itself to a succession of multiple shots like with a digital camera. I frame the image with my eyes first and then set up the camera accordingly.

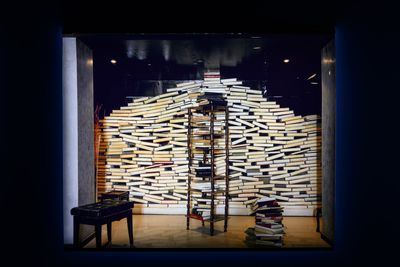

NKYour work also laments the demise of analogue photography. 'Background' (2012) is a nostalgic look at the disappearance of painted, scenographic backdrops in photo studios in Amman, Alexandria, Beirut, Cairo, and Istanbul, something that is happening due to digital photography.

HSFor me, it's about the death of an essential element of our daily lives and culture in the region: getting photographed in a professional photo studio. This was a profession that was very much alive until digital photography took over. I see its disappearance as a merciless phenomenon.

NKThis links to 'My Father and I', which comes to terms with the closure of your father's Sarkissian Photo Center. What was it like to have your father take these images of you?

HSDuring the session, my father and I had a very tense conversation, but neither of us actually said a word. Both of us were visualising the end of a journey—looking at this same moment with sadness and anger.

NKWhen your father decided to become a photographer instead a mechanic working in a garage, did he already have a passion for it?

HSNo, he wanted to get out of being a car mechanic in Aleppo. For the first 30 years of his career, before he opened the lab, he was a commercial photographer. He had always intended to become an artist, but he thought art would never put bread on the table.

NKIn Homesick (2014), was it cathartic to film yourself destroying a replica of your parents' apartment in Damascus? Was it a way of letting go of your home during the war in Syria?

HSI didn't want to let go of my home, I wanted to let go of the constant fear of our destroyed home. I wanted to break this image in my mind.

NKCan you say more about the separation of the work into two parts?

HSThe two parts are very distinct. One is the crumbling architectural landscape, which is actually a series of still images rather than a video. The other is the emotional landscape of me wielding the hammer.

NKWas this one of the first times you used video and why?

HSYes. When I finally felt able to address the war and unending violence in Syria in my work, I expanded into different formats. I started to develop new concepts for the difficulties I encountered and used photography to reflect these thoughts.

I've worked with moving images in two projects: Homesick and Horizon (2016), although, subconsciously I kept looking and thinking as a still image-maker. Yet my approach remains unchanged; I try to engage viewers behind the surface of what is visible, to re-evaluate larger historical and social narratives.

NKWith Final Flight (2018–2019), which explores the movements of the endangered northern bald ibis, you have varied the installation by including a video, a print, a relief, and seven casts of a 3D skull. How did your interest in the northern bald ibis begin?

HSThe northern bald ibis is one of the rarest birds in the world. They were the last known living descendants of ibises depicted 5,200 years ago in the oldest Egyptian hieroglyphs. The ibis is also mentioned as a sign of fertility in the Old Testament, while Muslims believed that the migrating birds guided pilgrims during their hajj [pilgrimage] towards Mecca.

I saw ourselves in these birds through their migration, extinction, and being killed by hunters, or electric cables.

After having been declared extinct in 1989, in 2003, a surviving colony of seven was discovered in the Syrian desert near Palmyra with help from the local Bedouin population. The tiny colony was intensively studied and protected until the war in Syria broke out in 2011. It disappeared again around the time Palmyra was destroyed in 2014.

After reading an article about the northern bald ibis in Syria, their existence and disappearance, I was struck by the similarities with stories of what Syrians were enduring during the war. I saw ourselves in these birds through their migration, extinction, and being killed by hunters, or electric cables. So I got in touch with Gianluca Serra, the ornithologist who studied the birds in Palmyra, and lived there for nine years.

NKHow did you find one of their skulls in Andalusia?

HSWith the help of Gianluca, we tracked down several zoological and natural history museums where the skulls are held. In the end, a zoo in Andalusia kindly allowed me to borrow a northern bald ibis skull to enable the 3D scanning.

NKSound has entered your work rather recently. Where Homesick is expressive and visceral in its sound, Deathscape is more abstractly violent, surrounded by black panels that relay recordings of the unearthing of mass graves from the time of Francisco Franco's fascist rule in Spain. How did you reach this point of eliminating the image?

HSWhen I was realising Deathscape, it was evident to me that I didn't want to include visuals, so I only relied on the sound from the exhumation process. I wanted audiences to conceive their own visuals based on what they were hearing. My images are about repression and silence, and here, the sound envisions the image. They are two sides of the same spectrum.

NKHow did you create the sound during the forensic archaeologists' digs?

HSIt was not possible to attach microphones to the archaeologists' bodies, so I worked with a sound engineer who arranged microphones inside the grave. And sometimes we used microphones attached to a very long arm to get closer to the tools used.

NKYou've been working with your father in Damascus and showing footage of your ancestral village Khantsorig for Sweet and Sour, a new project you will be showing in Bonnefanten. Can you say more about the project?

HSI went back to my grandfather's village in eastern Anatolia. He had a family there before meeting my grandmother. They were killed during the genocide. He was never able to return from Aleppo, where he was working. He never heard from his family. My grandmother also lost her family and they never spoke about this to their children.

I went to the village last year and shot scenes from the Sasoun region, one of the places where 90 percent of Armenians were killed. I will show these to my father, who has never been there and film his facial expressions.

NKSo the face becomes an emotional landscape. Can you say more about your process of filming in Khantsorig?

HSI got myself a video camera, but I use it like photography, so it records moving images as if they were still. What I do is find tiny details in the image that change or move, like a cat crossing the frame. There are no humans in these images. —[O]