Kristaps Ancāns: Propaganda Now

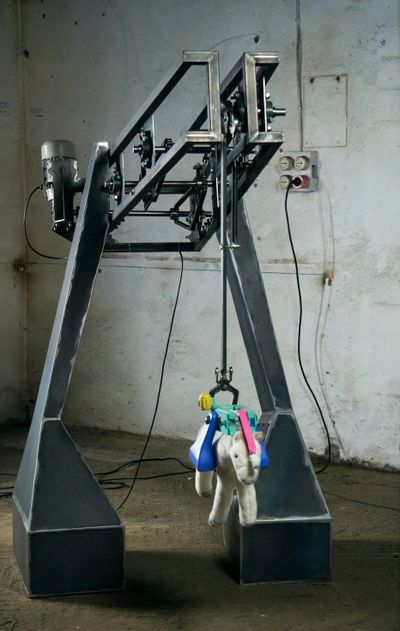

Kristaps Ancāns. Courtesy the artist.

Kristaps Ancāns. Courtesy the artist.

Latvian-British artist Kristaps Ancāns explores the relationship between humans, nature, and machines through an evolving conceptual game—an approach that the artist discusses in this conversation with theorist Boris Groys and curator Corina L. Apostol.

More specifically, Ancāns elaborates on what can't we just create (2021–2022), a site-specific installation consisting of monumental textual, photographic banners, and a large-scale sculpture, which previewed at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Daugavpils, Latvia, on 21 December 2021. The project is up through 30 June 2022.

Staged in the arsenal building of the Daugavpils Fortress, the project marked the first time the Centre exhibited outside of its premises, with Ancāns deftly making use of the abandoned Soviet-era building, which is covered in green mesh. With the ground frozen from snow and two bare linden trees nearby, a stark frame guided viewers' gazes across the scene.

On the building's external walls, two large banners hovered slightly above the ground. The title of the installation, in black typeface, is repeated in Latvian, Russian, and English, printed on a white banner mirroring the sheet of snow below. On the banner, the artist gradually fragmented the title to create a lyrical poem, forming new associations between acts of creation, possibilities of action, and patterns of thinking.

A tripartite banner, perpendicular to the latter, reveals a candid and unstaged portrait of a young woman named Nastya, who is putting together a toy dog from a Kinder Surprise egg. Facing the banner, a collapsed palm tree sculpture made from aspen, a local wood, rests between the linden trees, appearing fragile and solid against the harsh winter environment.

Vulnerability, playfulness, and stark contrasts balance the installation's double viewing positions, from the banners and their text and images to the sculpture and back, asserting the primacy of human bodies and how the construction of language impacts physical experience.

As a classically trained painter, Ancāns works with 'the context itself' to create site-specific installations as open-ended experiences. His projects embrace non-traditional installation materials and demonstrate a free-spirited approach, and a keen awareness of site-specificity reflected in the details of each piece.

For viewers, these projects generate a heightened awareness of seemingly quotidian buildings and sites. Among them, Have we all learned how to be human at home? (2021), installed over the threshold of London's domobaal gallery, is a sculptural installation consisting of a laser-cut steel arch from which the question has been carved out from rusted metal.

The installation facing passersby in central London was installed as pandemic lockdown restrictions eased across the U.K. in March 2021. With a touch of dark humour, its question functioned as a warning—an already critical situation was about to get worse. Conceptually, the work became an unstable sculpture, eliciting a flux of responses from audiences.

How do you help a butterfly with wet wings? (2021), a site-specific installation for the open-air exhibition Publiek Park in Citadelpark in Ghent, Belgium (2021) consisted of a white banner inscribed with the words from its title in bold, capital letters, draped above the gatehouse like a narrow billboard.

In the sentence, the word 'HOW' is crossed out with a red line resembling graffiti to introduce a double reading. For the artist, the question(s) irreverently summon the park's culture as a gay cruising area, while commenting on the fragility and resilience of L.G.B.T.Q.I.A. culture.

This deliberate use of double meaning also borrows from the world of advertising and signage, hinting at the malleability of language and its context-specificity. Such interplays between art and life, and language's influence on perceived realities, are at the crux of Ancāns' work.

CAYou have trained both in painting and environmental art at the Art Academy of Latvia in Riga, Latvia. Probing the concept of classical training, you mentioned your primary material is the context itself. What made you question the limitations of painting?

KAPainting is a great tool for learning how to construct things. However, it holds many limitations, as the medium has been reconstructed, rebuilt, extended, and replaced. The word 'painting' itself has become embedded with so much context and holds so much energy that it already is a type of material.

What I like about the creative process is that you can create and construct by choosing materials: words, physical materials, locations, and so forth. It doesn't mean I can't use painting, only not as something that will frame my work before it is made.

In my mind, this format is so defined, in a way. I like to look for the format of the work to see where it will lead me and what kind of form it will take, even if, sometimes, it's not clear at the beginning.

In many cases, I use the principle of painting to construct my work, but look through its mechanisms when I am making the work, so the outcome is far from a painting. What lies in a public space closely relates to a landscape's relationship to objects brought into it.

BGFor the public art project what can't we just create, you use posters as a medium. Do they refer to an advertisement and/or ideological propaganda from the Soviet time?

KAI grew up with the aesthetics of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, without experiencing the Soviet period. In a sense, I lived with their forms without their contents. The poster medium itself has always been an advertisement, either for products or propaganda.

I am looking at how we can 'advertise' more questions, rather than make definitive statements.

Some people may say I am introducing propaganda on a monumental scale—of an inclusive, liberal society where people from different nations in the new East can live in one country.

In the last three decades, the new East was building up and trying to understand its identity, and I was doing the same with mine. The banner as a medium has given us an opportunity to go into public spaces, so what is the future of monumental propaganda?

Ultimately, I don't consider this work to be an advertisement or a Soviet propaganda poster. I am looking at how we can 'advertise' more questions, rather than make definitive statements.

We are allowed and able to construct questions without following the statements on banners as they did during Soviet times. The question on my banner emphasises the relationship between the different languages, and implicitly, between the communities in which they are spoken.

what can't we just create is, in a way, propaganda of our time, as I am allowed to question this relationship in the post-Soviet era and see how it has transformed.

BGWhat dictated the choice of location for your installation?

KAwhat can't we just create is situated in the city of Daugavpils, in the Latgale region of Latvia, adjacent to the Mark Rothko Art Centre. I was born not far from the city, so creating the installation in this very location has a very special meaning for me.

In a way, this environment becomes a very interesting material to work with. It's a very strange feeling as I would normally explore the world from the inside out. However, in this case, I was returning to discover something very close to me, and in a sense, to rediscover it.

It's like cutting your hand while working in the studio. You suddenly see how your skin bursts and how the muscles work; in the worst-case scenario, you even see your bone. We can look at our bodies from different perspectives. Sometimes it makes one sick and dizzy, as the cut crosses a boundary. But through this process, we discover our bodies while the accidental scars look alien.

The region you come from—the home, by definition—is at once a strict and fictional category. But when you make an artwork about it and use its context, it almost feels like you've crashed into a personal border—as if it's something sacred, and you have removed its aura. It's exciting and daunting at the same time.

This is the first time I have worked on a monumental scale in this location and used the city with its cultural heritage as material. I live between the U.K. and Latvia, so now I see this home context very differently than when I was growing up there. This work would be very different in any other city in Latvia.

During my first site visit, I was permitted to wander through the fortress, and while walking around, I saw an abandoned building with two linden trees. These trees appeared alien themselves—it looked like no one had planted them, and they had strange shapes.

I saw the apartment blocks of people living there, the massive car park, the Soviet-era military buildings next to the empire-era massive buildings that were created in a very short timeframe to defend the region against Napoleon's invasion, which never took place.

This environment has its own ecosystem, and I became intrigued about what is happening there; the nature is quite wild and overgrown with vegetation, and it feels transformed and rebuilt.

In a sense, the building itself indicated that there is a future, that something was going to happen there. It almost looked like a construction site; it suggested something about making, creating, and developing things.

CAFor this project, you recycled old, personal images of Nastya by mixing them with your own poetic texts. What came to mind first? The text or the image?

KAI think neither is more primal than the other. For me, it's more about completing an action: Nastya made a doggy, the palm tree is laying on the ground, what can't we just create?

Action holds a central meaning and these actions are parts of one composition; removed from their context, they become like removed artefacts in museums and lose their relationship to the environment or are replaced by where they come from.

I like to put physical effort into my work, come to terms with it by getting tired, and build a strange relationship.

The text highlights specific actions that are already embedded in the image: 'HOT RACING' on Nastya's T-shirt, and the trilingual text I added. I choose which action should be highlighted and then sculpt the context in a particular way, or dissolve it.

In this installation, each of the elements marks a space—an area they create, where things can be moved, translated, and pushed around in this geometrical site of contexts. If you think about the site as a rectangle, which corner is more important? Is it the space, or the line that creates the perimeter?

BGIn the installation, you address the notion of creativity. Your heroine, Nastya, is creative because she made a doggy. How important is it to make things with your own hands in a tradition of handiwork?

KAWhen we work with our hands, we interact with the world, and we understand it better as we interfere with it. Even when we use the computer to type, we feel the keyboard hitting back—the plastic material—and we adapt to that system.

Nowadays, handiwork becomes more alien as we have machinery to do the work for us. How does that change our perception of the world?

I like to put physical effort into my work, come to terms with it by getting tired, and build a strange relationship. In my project, there is a combination of things I made by hand, such as the palm tree sculpture, and others, like the banner, that are made by machines.

New ideas come from your desire to experience something—whether it is a material, a form, or information—something you are excited about.

To what extent is the machine an extension of our bodies? By experiencing the material, you can understand it, and by understanding it, you realise what it can become—its potential. You try to win over the material; you fight it, and through this, you see how it changes or shifts your perception. This knowledge is crucial to me.

Through the photographs in these banners, I wanted to capture a moment of happiness expressed by Nastya putting together a Lego toy in an age where we do not always see the fruit of our work, as it mostly stays digital.

We can work on things for days, weeks, and months—the result is usually immaterial. When you create something, and it takes a representational form, even if it may be something quite childish, you see the progress and understand that you can generate something.

There are a lot of things that we create for which we don't see the outcome—it stays somewhere out there, in the system. The Nastya banners are not claiming that she is creative because she made a toy dog. Rather, they point to the fact that when you understand you have created something, regardless of the scale, it brings the joy of creation.

CAYou always carry a notebook with you, immediately ready to draw up another sketch for a new project. What are the primary sources for your ideas?

KAI carry it mostly to write or put down lines. It can be very simple lines that sometimes remain references for a thought or an idea. In the early stages, I use writing to pin down the beginning of ideas while I allow my imagination to carry on and speculate possible outcomes.

New ideas come from your desire to experience something—whether it is a material, a form, or information—something you are excited about. I think that's why you can't stop creating things, you get addicted to the desire to experience.

I like the union between exploration and experience. In my childhood, I used to read texts from different religions along with National Geographic magazines. That's where I first encountered the phrase 'artificial intelligence'. A question came to mind: do we also possess artificial intelligence if, according to most religions, we were created by a god?

I like to approach my way of thinking as a type of artificial intelligence—gaining new experiences, learning, and evolving. There are no limits or categories to what you can explore or experience.

BGIs it possible to be creative without producing anything at all?

KAAccording to the Bible, even if we have 'bad' thoughts, we create sins. It is paradoxical that certain cultural writings almost impose a limit on thought by defining it as 'good' or 'bad'. We can create worlds in our minds, play, and be incredibly creative with our imaginations.

While reading books, we construct our own worlds through the structure presented by the author without creating something material. That's why I like to work with text; it gives you the freedom to be as creative as you can stretch your imagination. Words are also very strong tools to make conflicts and wars, and move countries and borders, depending on the speaker.

Many things we produce are not related to creativity at all, like damage or destruction, even though destruction can be made in a creative way. Damage, or deformation, can be very simple and even primitive. In a postmodern world, they are used as a method to develop form as an experiment and see if the deformation or damage can generate new forms.

If someone with spray paint were to add another word to the banners, it might create something brilliant or just be an act of vandalism. We observe that damage does not always produce something new, and experiments of damage can stay just that.

It is possible to be creative without producing anything at all if you accept the void as another shape of the form. —[O]