Pélagie Gbaguidi: The Body as Archive

Zeno X Gallery | Sponsored Content

Pélagie Gbaguidi. Photo: © Axelle Degrave.

Pélagie Gbaguidi. Photo: © Axelle Degrave.

In many African countries, writer Julie Crenn notes in her profile of Beninese and Brussels-based artist Pélagie Gbaguidi, 'griots are the depositaries of oral heritage, and therefore of a great responsibility: they are tasked with ensuring that stories, events, traditions, and legends live on from one generation to the next.'

'Griots are nomadic figures who pass on narratives, iconography, metaphors, songs, music, and poetry,' she adds. Gbaguidi adopts the ancestral figure of the 'griot' to move between past and present histories, as well as upending colonial legacies in a multidisciplinary practice spanning painting, drawing, performance, and installation.

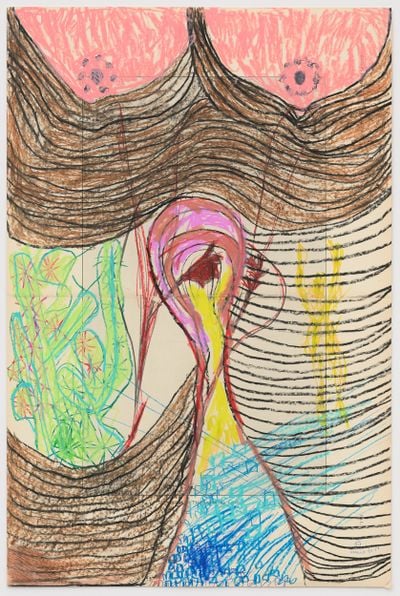

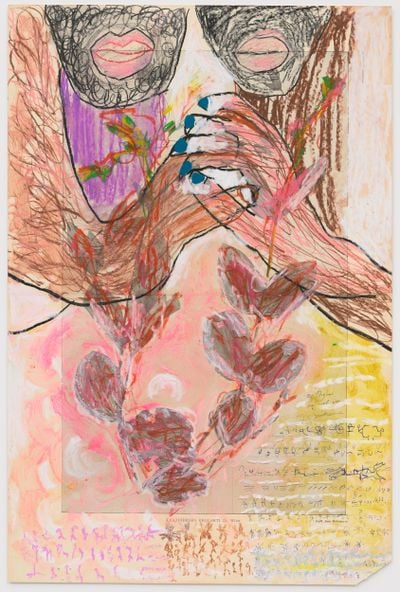

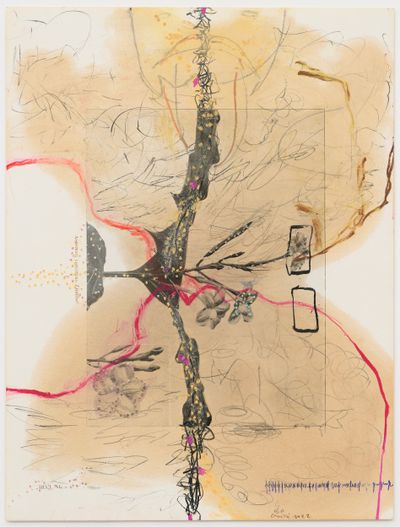

Moving freely between the pictorial and text, Gbaguidi's works are composed of evocations rather than recognisable representations. Across media, the artist uses memory work to probe given histories, with a focus on what is omitted and on what has not been recognised or recorded.

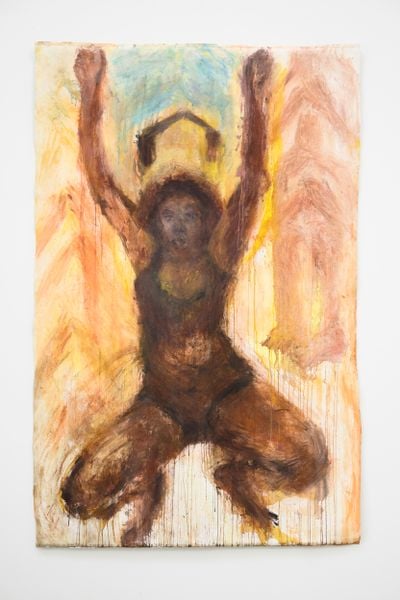

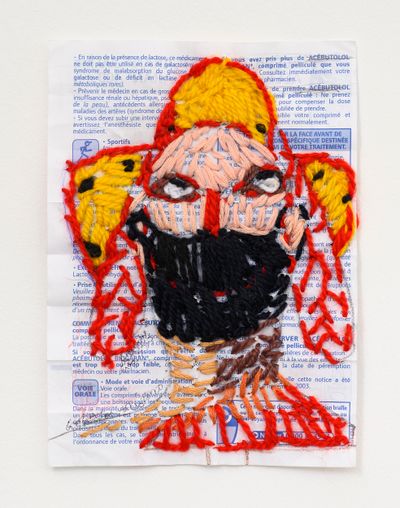

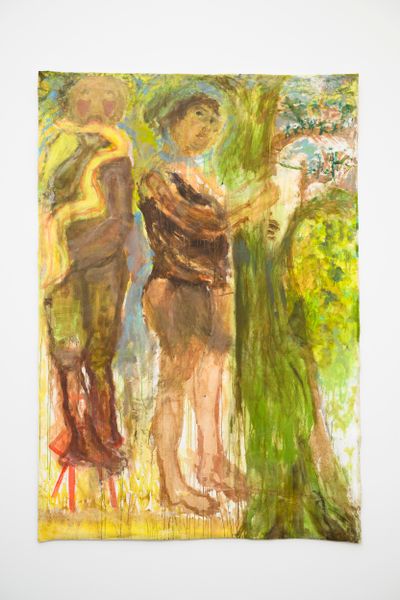

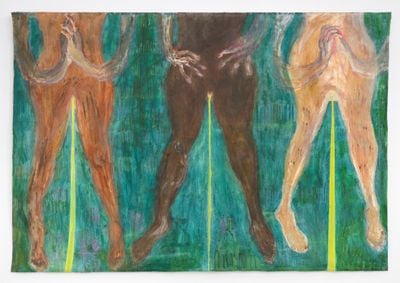

Acting as a link between past and present, the body is central to Gbaguidi's first solo exhibition at Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp (Le jour se lève, 16 March–29 May 2022) as as an archive and centre of exchange. Here, the body becomes a language that translates sociopolitical issues into a poetic choreography made up of paintings, drawings, and textiles.

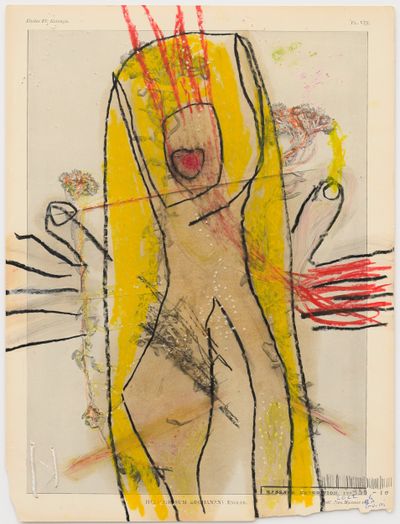

Among these, acrylic and pigment paintings on canvas in the gallery's second room, after which the exhibition has been titled, contain contours of the artist's own body upon which she has layered blurred, vivid hues, with figures reaching towards the sky or sun, as in the case of Le jour se lève: Unfinished (2021).

Whilst Gbaguidi looks to her own body as a repository of knowledge, she has also addressed official historical records in her work, including Le Code Noir—considered 'the bible of slavery' when it was conceived by the court of Louis XIV in 1685, and regulated the lives of slaves in all the French colonies until April 1848.

Following a residency at the Centre des Arts Contemporains in Nantes—an important city in the history of the French transatlantic slave trade—the artist made 100 drawings departing from Le Code Noir, which were purchased by Memorial ACTe in Guadeloupe, readjusting their meaning through images and texts to confront an ugly part of history that most want to leave unaddressed.

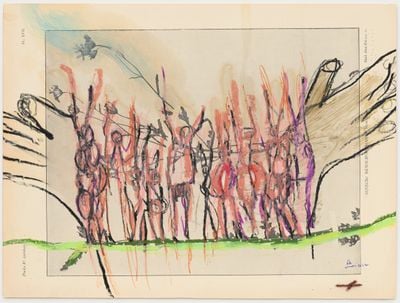

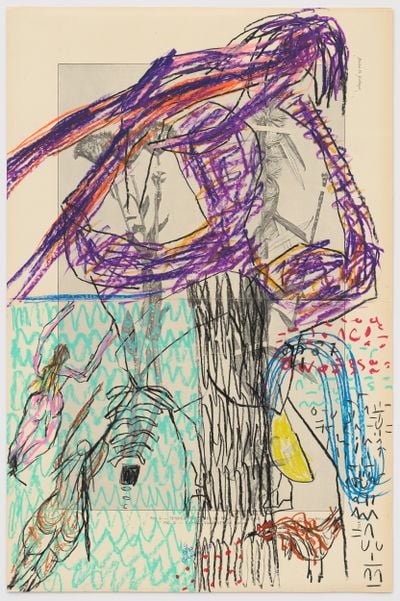

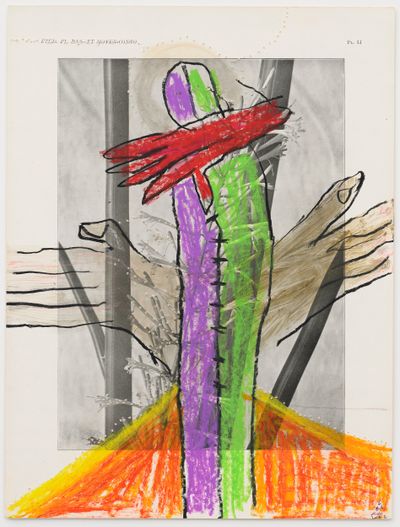

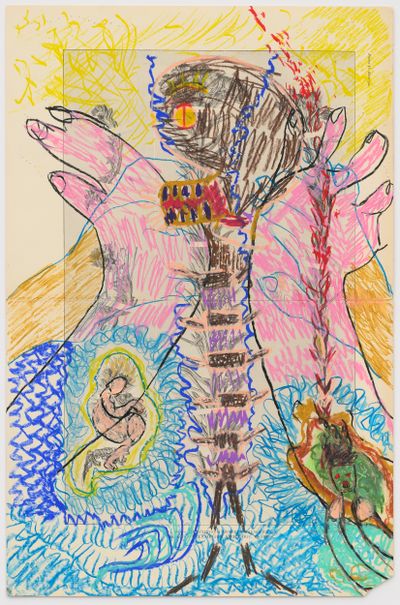

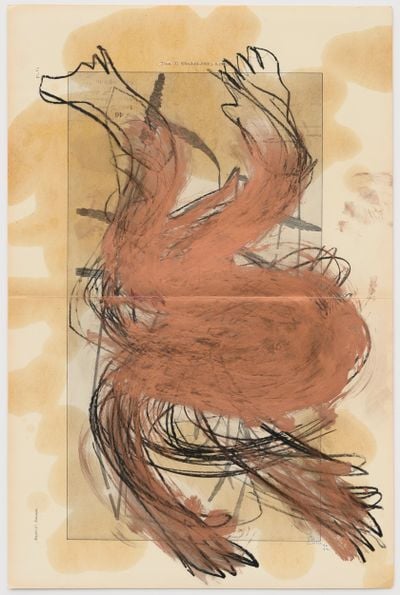

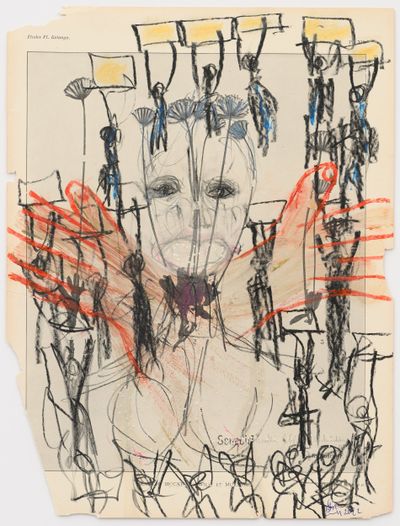

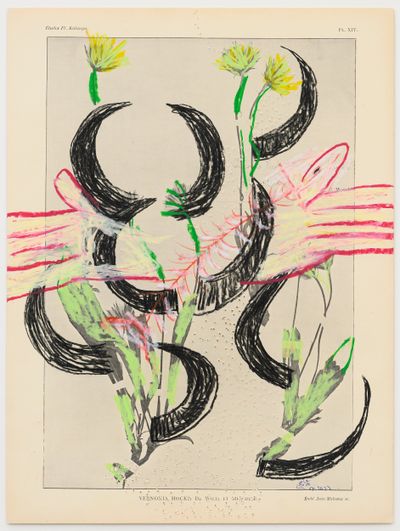

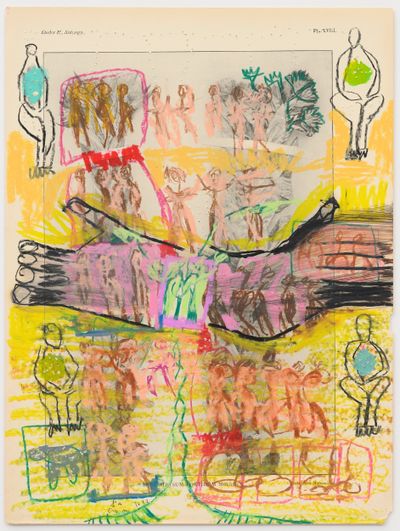

At Zeno X Gallery, Gbaguidi presents a series of drawings titled 'Chaine Humaine' (2022) on sheets of paper from an encyclopaedia of Congolese flora that she obtained from the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, near Brussels. Responding to these colonial efforts towards classification, Gbaguidi renders scenes of growth and movement, with occasionally violent clashes between figures upon the pages referring to collisions between individual and collective consciousness, and between repressed and current history in its decolonial process.

In the conversation that follows, Gbaguidi discusses her contribution towards this process, utilising griot methodologies to reveal how memory is constructed, written, and transferred from one generation to the next.

JDWhen did you begin to use the term 'contemporary griot' to describe your process, and how have its designations—of West African historian, storyteller, keeper of history, praise singer, poet, or musician—helped expand your art practice?

PGThe posture of the griot imposed itself on me like a revelation. In 2000 or thereabouts, the questions I began to ask myself were existential: How, as an artist and woman, could I give meaning to my life? How could I make a mark on time?

I am an archive, we are archives, and if we share them, we might better understand ourselves and the world we live in.

These questions were urgent in my consciousness, because we seemed to be arriving at a radical moment, when the digital revolution of the 21st century began changing our perceptions of reality. I began wondering how to analyse my own history, and in a broader sense, history in the contemporary art space.

I then considered my artistic language and the dimension of orality, remaining aware of mutations of oral traditions and the junction between new aesthetic forms of orality. Among the most prominent questions in my mind, was: What is the place of orality in contemporary society?

As I mentioned, the figure of the griot imposed itself on me, and it manifested in my works as an extension of African cultural heritage, but with an innovative desire to transcribe memory and collective trauma inherited from the colonial system into an artistic language.

I came up with the following statement to reflect this: 'The "Griot" questions the individual as he or she moves through life by absorbing the words of the ancients and modelling them like a ball of fat that it places in the stomach of each passer-by with the ingredients of the day. In the practical sense, it breaks the commonplace rhythm by inserting subtle incidents integrating its part of eternity.'

During my research, I became interested in the repercussions of this history on a psychological level. I undertook a work of transformation through my practice, transforming individual trauma into an archive, then into a collective excavation.

I am an archive, we are archives, and if we share them, we might better understand ourselves and the world we live in.

JDThere's also the question of the disappearance of figures such as the griot, and in a way, you're adopting and working in griot traditions. This helps keep traditions alive for next generations.

Given that West African traditions—and African traditions in general—relied so heavily on oral transmission, would you agree this was an appropriate framing of your use of griot as a working method?

PGYes, orality and transmission raise several questions around collective amnesia of this sensitive issue of colonial neurosis and its corollary of violence; of institutional racism.

How can we find ways to transmit today through the digital revolution? Is this important for the survival of the human species? As reflected in Édouard Glissant's archipelagic thinking, it is important in maintaining an ecology of wellbeing, thought, and relationships.

Through the griot, I am asserting myself so that this 'tipping' will not be forgotten. Several centuries ago, there was a clash of civilisations. Slavery, lasting four hundred years, has left traces, stigmata, wounds, and many more ravages. From there, colonisation became a continuum.

I reflect on the events of the past on today's society. It also makes me feel that we all failed as human beings. The figure of the griot has taken shape, like a postulate; at the crossroads of memory, history, orality, and image. This hybridity is a catalyst in my artistic approach.

My vision as a griot is a commitment to creating a bridge between traditional and contemporary realms via different media. I read all the signs together to weave a daily life that resists changes.

My work revolves around the idea of seeing speech and images as signs that need to be deciphered and transmitted. The poetry, drawings, paintings, narrative rituals, and photo objects all create open spaces from which I draw contemporary forms.

In this sense, my work reflects the urgency of expressing our experiences, to be witnesses of a narrative journey and to share it as material, because each told story is a gift for a new one.

JDHow do you reconcile working with trauma itself as a transgressive tool to keep the past relevant and not forgotten or misremembered? I am thinking here of your work deconstructing Le Code Noir, for example.

PGLe Code Noir is a historical document—a legal text of 60 articles promulgated by Louis XIV in 1685. It was considered the bible of slavery. It confirmed the foundations on which the master-slave relationship was to be forged over centuries, leading to dramatic results.

I became interested in Le Code Noir in 2004, and it was a crucial point of my journey. I heard about it long ago as a child in school, but it was very brief, so it got buried in the deep crevices of my memory.

In 2004, I was invited to a residency project linked to the Dakar Biennale at Le lieu unique in Nantes. There, I rediscovered Le Code Noir at a book fair in Nantes, which was the first slave port in France!

It was a revelation for me—a sepulchral place in France that was integral to the tragedy of the slave trade, being the departure point of slave ships destined to embark African slaves for exile and deportation between the 17th and 19th centuries.

I learned a powerful lesson from Nantes, that no matter how you try to escape from your past, it will eventually catch up with you.

I started to document the historical trauma between Africa and the rest of the world through the process of Le Code Noir in the context of different countries. I called them landscapes, or new visions of human geography.

Le Code Noir had a profound impact on me, and it is closely related to the concept of downfall. I reflect only on the mistakes of the past, to try to understand what we have fallen into.

Le Code Noir has become a research tool for analysing collective trauma inherited from continuous colonial violence.

To me, Le Code Noir is a tool to observe its reminiscences, distortions, and correlations with racism today and gender and social hierarchies. I began to confront this archive, to contextualise it through different periods of history before bringing it into the present and different places of memory.

I contextualised drawings of Le Code Noir in relation to Nazi Germany, producing a new series of 40 drawings. Then, a visit to an image archive at the Mauthausen Memorial in Austria led to a series of questions.

Other sites such as Gorée in Senegal, the Hector Pieterson Memorial in Soweto, South Africa; and The Door of No Return in Benin all also evoke the fall of colonialism.

Le Code Noir has become a research tool for analysing collective trauma inherited from continuous colonial violence—what Franz Fanon refers to as collective neurosis. It has become a work of introspection allowing for social, individual, and collective transformation; of excavation as social therapy.

In 2007, I was invited to the inauguration of the contemporary art space Casa África in Las Palmas, Spain. At the time, the Mediterranean Sea was being transformed into a marine cemetary. The bodies of refugees that ran aground on the sunny beaches began to install a malaise.

During my stay, I had a dream of shipwrecks coming to life and approaching passers-by, asking them for everything they had. They were saying, 'Give me your house; give me your car'. The cornered population gave everything it had; it was dispossessed.

JDYou have often used paintings and drawings to deconstruct stereotypes as they are projected onto ideas of articulating and understanding the nuances of Blackness and Africanness within the global.

In paintings and drawings from your project El Mundo Sans le Corps, exhibited at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in 2021, the physical body is reflected as a carrier of memories. How have archival materials assisted you in establishing your role as a griot, artist, and teller of stories?

PGMy answer could be summed up in the question, 'Do you hear the lamentations of the trees?' When my body becomes a ball of fat crossed by human geographies in a time shaped by a specialised syncretism—I mean, a mixture of past, present, and future—the artwork becomes a wave.

The toxic material—linked by the colonial archive—is being treated through rhymes that are sung through poetry, painted, drawn, and ritualised through performative gestures. Every drawing is a celebration that escapes trauma—a small victory over the psychological horror of our times.

JDFor the 6th Lubumbashi Biennale, you presented the expansive installation Echo museum – the archive and Udji Kinge—described as 'a video about performances in ore quarries, intended to reveal psychological spaces affected by social and political issues'.

I feel this resonates with Achille Mbembe's book Necropolitics (2011), where colonial occupation is addressed as a matter of seizing, delimiting, and asserting control over a physical geographical area—of writing on the ground a new set of social and spatial relations.

In my view, there is still a disconnect between the extractivism of materials, environmental degradation, and its relationship to the spaces we inhabit; or rather, spaces being the raw material of sovereignty and the violence it continues to carry with it.

Could you expand a bit on the importance of what you have described as 'the urgency of starting a decolonial ecology'?

PGAs I mentioned, Le Code Noir functions as a memorial object that carries the traumas of the slavery era but also functions as a pedagogical tool to understand the mechanisms of enslavement and the fabrication of ideologies of race; of social categorisations.

Regarding ecological aspects, I have developed a related line of research by considering nature as a physical and organic archive.

In this sense, the discovery of the prehistoric sites in Sterkfontein deeply inspired me, and has an even stronger resonance today in the register of decolonial ecology—referencing the work of Malcom Ferdinand—and how nature is a witness to all these tragedies and crises we are going through. They all have their roots in this period of devastation that begins with imperialist conquests. All these links are invisible, however, because we compartmentalise different struggles.

Anti-racial, feminist, and equal rights and freedom struggles should find a common ground, because they ultimately stem from the violence of colonial heritage and imperialism as current markers of global economic, identity, and ecological crises.

These are key issues in the decolonial debate today. It is also important to become aware of the impact of the system of natural resource predation on bodies—that green energy sacrifices human lives in the name of 'technological progress'.

My work revolves around the idea of seeing speech and images as signs that need to be deciphered and transmitted.

In the mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo, women, children, and men are illegally extracting minerals, working with their bare hands, without protection in the sun, to reduce large stones to gravel. They fill buckets that they sell to survive. Three hours of work to fill a bucket costs 20 cents.

Finally, our 'eco-responsible' actions are linked wherever we live on this planet to make an economy of relationship—a moral ethic of mental wellbeing.

JDIn the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, how have the intersections of contamination, containment, and politics of segregation informed your current work?

PGOne of the most tender images I saw in the street of a village of 4,000 inhabitants during lockdown, while on an afternoon stroll with a friend, was a couple both wearing pyjamas. They walked supporting each other. They were protected by a great aura. Going out in pyjamas seemed to me to be the greatest victory over conventional attitudes. He had widened the walls of containment.

At a time when it was difficult to find answers to the torments caused by the health catastrophe, I began to talk to the flowers in my garden.

During this time, I was reminded of Jacques Derrida's inquiries into sovereignty. I was not in search of sovereignty; rather, I was in demand for dialogue with nature, in demand for care, in demand for mother earth's reparation. This question came to me: what do the flowers think of our malpractices towards nature?

The features of my drawings brought me back to the essential, and reactivated the sense of the collective. They allowed me to make more room for the invisible and put it naked. Reborn by the elementary gestures of everyday life and conversation.

We all know where the policies of ultra-surveillance, control, supra-security, and the separation of one group from another have taken us. One of my latest projects, Hunger, created with a collective of artists called On-trade-Off at Z33 Hasselt, raises the issue of hunger in the world. The starting point of this new research refers to the question: Why do we not talk about the causes of poverty?

Through his work, Argentinian philosopher Walter Mignolo poses the question: What kind of knowledge do decolonial thinkers want? We want knowledge that contributes to eliminating coloniality and improving the conditions of life on the planet.

For example, a hegemonic political concern is the fight against poverty. Most research into poverty explains why we have poverty in the world. Decolonial knowledge, on the other hand, aims at revealing the 'causes' of poverty rather than accepting it as a fact, producing knowledge to improve living conditions on the planet and producing knowledge to reduce its spread.

From there, I wish to deconstruct preconceived ideas to continue the process of decolonisation, to achieve a transformation on this taboo phenomenon by defusing the ideas cemented on three central issues: hunger, poverty, and capital.

In my solo exhibition at Zeno X Gallery, Le jour se lève, the question of pain and the continuous and latent violence linked to collective neuroses is raised.

In this exhibition, I ask the following questions: How can we exist without dominating others? Why does society need human capital? What is the link between the object and the subject in the capitalist world? —[O]