Into the Blue: Dhaka Art Summit 2018

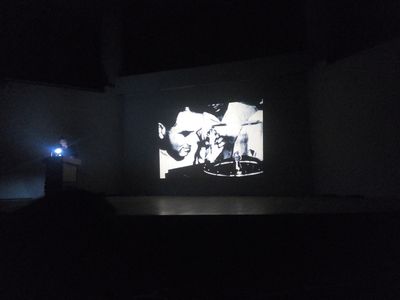

Ursula Biemann, Deep Water (2013) (Still). HD video. 9 min. Courtesy the artist.

By virtue of its approach—to present contemporary art from around the globe with a focus on countries usually left out of the art map—DAS challenges colonial cartographies by uprooting the notion that the West has always been the centre of art and culture.

'Water is declared the territory of citizenship', whispers a voice in Ursula Biemann's film Deep Weather (2013). A camera pans the Canadian Arctic's tar sands—a series of toxic lakes and darkened swelling seas—then moves seamlessly to the shores of Bangladesh, where climate refugees repeat the futile act of moving heaps of sandbags to line the rims of their homes, submerged due to rising waters as a result of melting ice from the Himalayas. 'Land is little more than a constantly fluctuating, mobile mass'—hushed words tell their own story about the dispersal of data, sonically transforming the narrator's nonchalance into an SOS. By placing two regions seemingly far apart into such proximity, Biemann rearranges the map by visualising networks of connection, complicity and control.

Deep Weather was a pivotal work of the fourth iteration of the Dhaka Art Summit (DAS, 2–10 February 2018), throughout which references to the colour blue, and the oceans and seas that are associated with it, became a consistent metaphor utilised to express fluid connections between things. The video featured in Bearing Points, organised by DAS's chief curator Diana Campbell Betancourt and staged throughout Shilpakala Academy, the national academy of fine and performing arts where the Summit is held. This curatorial presentation replaced what used to be the Solo Projects section of the summit, with 'large-scale thematic presentations' intended to orient viewers 'towards lesser explored transcultural histories of the region' by 'weaving together strands of thought' among the summit's 'nine other guest-curated exhibitions'.

Featuring some 45 artists, artist duos and collectives, from Rasheed Araeen to The Otolith Group (Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun), Bearing Points was divided into five sections, 'Dozakh-i-puri n'imat—An Inferno Bearing Gifts', 'Residence Time', 'An Amphibious Sun', 'There Once was a Village Here' and 'Politics: The Most Architectural Thing To Do'. Exhibited in 'Politics' was Studies in Form (2017-2018) by Seher Shah and Randhir Singh: blue cyanotype monoprints depicting brutalist buildings in London (The Barbican Estate and Brownfield Estate), Delhi (Akbar Bhawan), Dhaka (University Library) and Tokyo (Dentsu Head Office) alongside speculative architectural drawings.

Shah and Singh's futuristic nostalgia for these buildings—testimonies to the (failed) utopian ideas surrounding the engineering of society into a functioning whole in modernist architectural design—found their counterpoint in Munem Wasif's set of blue cyanotypes that comprise Seeds Shall Set Us Free (2016-ongoing). Shown as part of the section 'There Once Was a Village Here', Bengal's multi-purpose rice seeds appear like floating creatures in a viscous ocean. The prints at once reference the agricultural colonialism of monocultures and genetically manufactured seeds, which produces cycles of debt and despair, while proposing an alternate ecosophical cosmology by interpreting grain as 'a companion species to humanity'—complete with 'names, deities and spirits'—'around which the village organises itself'.

For Betancourt, works like these 'are blueprints for futures that no longer exist'. Their intention, she explains, is 'to look to the past to imagine our way forward in this populist capitalist world of binaries'. The same could be said of the Dhaka Art Summit, launched in 2012 and held biannually in Bangladesh's capital, Dhaka, under the Shilpakala Academy's roof. Alongside the nine curated exhibitions presented within the building this year were the Samdani Artist-Led Initiatives Forum, comprised of presentations from 12 local organisations; the inaugural Samdani Architecture Award won by Maksudul Karim, whose Shadow Boat consisted of a large upturned bamboo boat that doubled up as the Summit's Educational Pavilion; and a new iteration of the conference Critical Writing Ensembles titled Sovereign Words: Facing the Tempest of a Global Art History—a project proposed by the Office of Contemporary Arts Norway involving newly commissioned texts by Indigenous artists, law scholars and conservationists from around the world.

By virtue of its approach—to present contemporary art from around the globe with a focus on countries usually left out of the art map, including Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam, Indonesia, Cambodia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Iran, Mongolia, and Afghanistan—DAS challenges colonial cartographies. It does so by uprooting the notion that the West has always been the centre of art and culture, and rerouting avant-garde experimentation through South Asia. The result is a diffusion of the dichotomy of 'East/West' entirely. 'South-Asia' is not only found within [the region's] geopolitically defined borders', writes Betancourt in her introduction to DAS 2018; South Asia is everywhere, she seems to say—and everywhere is everywhere.

At DAS 2018, this central idea was epitomised in Desmond Lazaro's Dymaxion Map III, Continents (2018), presented in an exhibition inspired by the work of architect Buckminster Fuller, Planetary Planning, curated by Devika Singh. (Not to mention the fact that many of DAS 2018's exhibitions and commissions will travel throughout 2018: Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran's ceramic sculptures articulating a cross-cultural religious fluidity will travel to Artspace Sydney, which co-commissioned the work, for example; and Reetu Sattar's performance, HARANO SUR, will be shown at the upcoming Liverpool Biennial.)

Planetary Planning featured 12 artists including Zarina Hashmi, Isamu Noguchi and Lala Rukh. It used Fuller's eponymous Nehru Memorial Lecture, delivered in Delhi in 1969, as a starting point. As Singh writes in her introductory essay, Fuller 'claimed that South-Asia could be conceived as a form of axis-mundi and a cradle for all humanity'. Works used the region's history of modernist architecture to create subtle, striking connections between lines and lineages while simultaneously dismantling them. Dymaxion Map III, Continents, for instance, depicts Fuller's vision of a world map, in which the Earth is flattened onto the surface of an icosahedron, so that it is aired out, with no right way up, eliminating directionality and dominant hierarchies. In Lazaro's version, this map is gold-gilded and references the artist's personal history of migration from Pondicherry in India to the UK, and the membranes of memory that this movement negotiates.

In total, DAS 2018 welcomed around 317,000 visitors. Yet, while much of the summit's 'success' is often judged by the arterati in attendance from American and European institutions, the real triumph is the large numbers of local school children that visit, many of whom rarely have a chance to engage with art in such diverse historical and geographical contexts, thus opening up radical ways of learning. Supported in large part by the patronage of the Samdani Foundation and assisted by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Para Site in Hong Kong, and TS1 in Yangon, all events were free to enter and consistently unafraid to be subversive.

Take the exhibition curated by Para Site's Cosmin Costinas: A Beast, A God, And A Line. The sprawling show—which will travel to Para Site (17 March–20 May 2018), TS1 (9–24 June 2018) and to Warsaw's Modern Art Museum (20 July–7 October, 2018)—features 49 artists from the Pacific to Madagascar. In the wake of imperialism, populism and fundamentalism, the exhibition (according to its curatorial statement) considers the 'connections and circulations' of ideas, information, objects, ideologies, skills and sorrows across the geographies of the Asia Pacific, taking the Bengal region 'at its core'.

Among the works on view were shawls embroidered by master weaver Zamthingla Ruivah, who embeds images of dissent in her fabrics to commemorate the violence inflicted on her native Nagaland in North Eastern India by the Indian army. The Luingamla Kashan (1990-present), for instance, are a series of shawls made in memory of Luingamla, an 18-year-old girl who was killed by the Indian army for resisting sexual assault. Sewn onto red cloth are repetitive, geometric motifs that represent animist symbols, which were lost when the community was converted to Christianity. Immune to the interpretations of the Indian government, the garment is an ultimate act of subversion that abstractly testifies to the support and unity that followed Luingmala's death. Today, these shawls represent a symbol of community, and are worn by women in the area as a sign of solidarity.

Also standing in peaceful protest, albeit as a reminder of a different historical struggle, was Manish Nai's Untitled (2017): five large sticks wrapped in compressed strips of burlap dyed indigo leaning upright against a wall. The work recalls the bloody history of indigo planting in Bengal, when the British turned farmers from food to indigo cultivation, offering loans at interest rates that left farmers, forced to convert their crop, in debt. (The frustration and despair caused by the resultant precarity swelled into an uprising in 1859 that was violently suppressed by colonial forces.)

Giving the theme of uprising and upheaval global resonance in this exhibition was Nabil Ahmed's three-channel video, Radical Meteorology (2013): an animation of the iconic 'Blue Marble' image from 1972, the first image of the whole planet—from the Mediterranean sea to Antarctica—taken from outer space. It was one of the most widely distributed photographs in history and especially significant in providing a sense of unity post-Cold War. Ahmed's animation is a slow zoom into Bangladesh, where the 1970 Bhola cyclone is brewing. (This natural event left half a million people dead or displaced and led to the Bangladesh Liberation War.) The work seems to suggest that the world, though presented as unified, is intimately entangled in violent upheaval. In this forensic investigation of a single geosophical image, the historiography of an image is put into question, imploring viewers to take into account the image-maker before concluding what is actually seen in a given representation.

This insistence on zooming in on the granular details making up the realities of an expansive and fluid world was reflected in the 4th Dhaka Art Summit as a whole, with exhibits that felt like deliberately mapped nodes designed to connect different spaces and times. This was especially palpable in curator Vali Mahlouji's stunning show, A Utopian Stage: Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis, organised by Mahlouji's non-profit curatorial and educational platform, Archaeology of the Final Decade. The exhibition unearthed archival material in the form of posters, films and audio recordings, diaries and drawings, from the Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis, which took place every summer in Iran for a decade between 1967 and 1977, before the religious decree that censored all culture. During its time, the festival brought together voices from Asia and Africa in direct contact with those from Europe and the Americas. (Now here's a 'scene and heard' if there ever was one: Ravi Shankar, Jerzy Grotowski, Robert Wilson, John Cage, Max Roach, Shuji Terayama, Vilayat Khan all shared a stage at the Festival of Arts, creating new work that remained taboo in their own countries.)

A Utopian Stage was compressed with awe-inspiring material, placing art historical movements in such proximity that the exhibition seemed to embody the movement of a whirling dervish. Supporting a series of Merce Cunningham film clips, for instance, was a series of live and improvised instructional sessions by the dancer Silas Riener, from the Merce Cunningham dance company, which followed through on Mahlouji's insistence that the archive is always alive.

At the height of the Cold War, Mahlouji explained in conversation, the Festival of the Arts—a 'post-colonial intellectual project' that 'aspired to provide opportunities for an inter-cultural juxtaposition'—sought to create 'a contrary utopian unity of disunities' that radically dissolved power dynamics between metropolitan and rural, and centre and peripheral. In the context of the Dhaka Art Summit, this radical dissolution was reflected in the present moment, with A Utopian Stage gesturing towards the Dhaka Art Summit as a version of this historic festival, albeit with a distinctly 21st-century approach. (The Shilpakala Academy has hosted the historic Asian Art Biennale since 1981; a selection of 26 works from its first four editions are on display at this edition in a presentation titled Asian Art Biennale in Context.)

Adding another layer of self-reflexivity to DAS 2018's programming was Matti Braun's lecture-performance, 'Vikram Sarabhai', presented on 4 February as part of the Illustrated Lectures programme. 'Vikram Sarabhai' used 35mm slides to tell the story of an Indian family, based in Gujarat, with a truly international vision. The family were made up of Mrinalini Sarabhai, an acclaimed Bharatanatyam dancer, her husband, Vikram Sarabhai, the founder of India's space programme, who also set up the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts with his wife in 1949. Their daughter, Mallika Sarabhai, is an Indian classical dancer and activist, and their son Kartikeya Sarabhai is a leading environmental educator and dedicated community builder. The slides Braun showed reflected on the family's friendships with India's former Prime Ministers Jawaharla Nehru and Indira Gandhi, as well as Mahatma Gandhi, not to mention international architects, dancers and artists including Alexander Calder, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Louis Kahn, John Baldessari, and many more.

The Sarabhai family villa was filled with commissioned art, and in his lecture, Braun imagined the conversations that might have taken place there as networks of ideas and empathetic transfers that preceded the internet, foreshadowing the possibilities of varied and coexisting truths. If there was and is any way to truly imagine post-nationalism, Braun's lecture seemed to suggest, it is through and within the fluid realm of art, where territories feel more like water than solid land. As a whole, DAS 2018 appears to have set sail with this idea; never claiming a centre, and dropping anchors at multiple harbours instead. —[O]

—

—