Nilima Sheikh

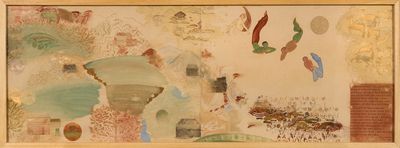

Nilima Sheikh applying stencil on her work. Courtesy the artist.

Nilima Sheikh applying stencil on her work. Courtesy the artist.

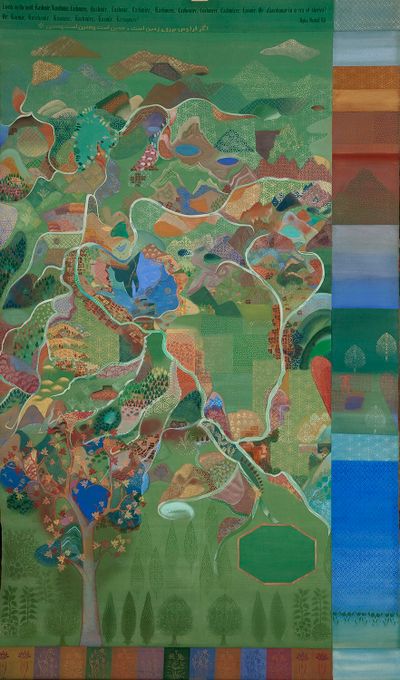

Nilima Sheikh says it was a different time then. Though always true, what she is describing is the specificity of her life as an artist in India. Born in New Delhi in 1945, Sheikh trained in Baroda, where she now lives. Her paintings contain world lexicons, written in a language she has developed over the last four decades. Integrating source materials that range from Turkish, Persian, and Indian manuscript painting, to literary excerpts from the poetry and writings of Mahmoud Darwish, Li Bai, Mirza Waheed and Chitralekha Zutshi, Sheikh considers how people identify with a larger collectivity. In layers, her landscapes trace contested histories of Kashmir, the partition of the Punjab, and violence against young Indian brides.

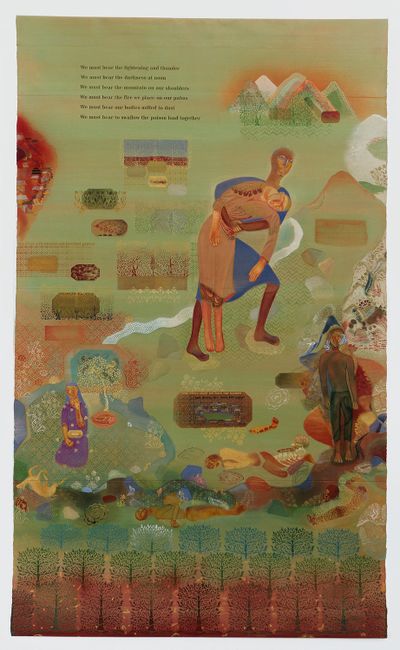

Two exhibitions at Mumbai's Chemould Prescott Road, one in 2003 and another in 2010, demonstrate the artist's concern with the tumultuous history of Kashmir. In the first exhibition, The Country Without a Post Office: Reading Agha Shahid Ali (9–30 April 2013), Sheikh engaged with the territory's upheaval by responding to the words of Kashmiri poet Agha Shahid Ali. This concern was furthered in her 2010 exhibition, Each Night Put Kashmir in Your Dreams (29 March–30 April 2010), a series of nine casein and tempera on canvas paintings. In 2014, this series was expanded with two new works, We Must bear and Hunarmand, on the occasion of the artist's first solo museum exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, Nilima Sheikh: Each Night Put Kashmir in Your Dreams (8 March–18 May 2014). Through the amalgamation of meticulous details—from literary quotations to traditional stencils from Mathura—Sheikh's paintings come together as sweeping landscapes that traverse a cartography of divisive politics. A beautiful example of this, titled Sarhad 2 (2014), was included in the exhibition Lines of Flight: Nilima Sheikh Archive at Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong (22 March–30 June 2018), along with a series of documents from the artist's archive that provided an in-depth understanding of her trajectory as an artist.

In this conversation, Sheikh, who trained as a historian before studying painting, discusses the development of her practice, explaining how ideas around collectivity and the landscape, not to mention the influence of literature, have shaped her work.

HCIn 1987, you were one of the initiators of what many now call the Four Women Artists exhibition, which showed watercolour works by Arpita Singh, Nalini Malani, Madhvi Parekh, and yourself. Later called Through the Looking Glass, this exhibition toured to five cities. How did this journey begin?

NSIn certain parts of the country's social fabric, feminism was present as an understanding, but in the cultural field, it had entered only marginally. The notion of women getting together to do an exhibition was fairly new, so when we were planning a large exhibition of women artists, we came across many issues that left us a little uncertain. Who is doing this exhibition? Are we doing it? Are we doing it collaboratively? Are we doing it as the people who are judging? The notion of curatorial intervention was relatively unknown in our art world at the time. We felt that it would be detrimental to the sense of solidarity with other women artists if we were to select some and not others. That became a crisis. So, when a friend of ours suggested that the four of us exhibit together, we decided to show it at places that were accessible, rather than at very private galleries. That's how it started.

HCWhat was your biggest takeaway from that series of exhibitions and how did your idea of art-making change?

NSI decided to give primary importance to works on paper instead of oil painting. This was a choice I had made a few years prior to that exhibition. I would get comments from artist friends who were well meaning but not quite on the same tangent as me. They would say, 'Ah, this is good but when are you going to start painting?' As if working on paper was not painting. It was a different time. Up until then, the format of the framed canvas on the wall had so marked the modernist experience of art in India. That was one aspect. Another aspect was that although we were not working directly in collaboration, the notion of a collective of women practitioners became very important to me for the first time.

HCHow do you think working as a collective influenced you?

NSAn artist usually works in isolation. When you're working in collaboration, the notion of creative authority has to stretch. I think that helped me a lot. The notion of having authoritarian interest in my work dwindled and the quest was to develop a language.

HCDo you feel ownership of your work now?

NSIt's not that I ever gave up that sense of ownership or authorship; there are times when I work in a very personal and private way. I see the work coming entirely out of my hands. But I've also tried to stretch that, especially in my larger works. For instance, I use stencils made by craftspeople that live in a town called Mathura in northern India, who create decorative motifs in the service of Lord Krishna. Collaboration in this case has been heavily loaded on my side, but I hope they have also enjoyed it and have been able to extend their practice through interaction with mine. These elements are not necessarily my own, but they add meaning in all kinds of ways; the additive mode of the work is extended by adding things to it rather than containing it.

HCWould you consider the way your works are stitched together as a kind of history painting?

NSNobody has ever said that to me in that way, but you might be right. In some ways, I stitch together stories and information in a way that allows different elements to build up over time. I like my paintings to contain references to different times and geographies. In that sense, I use history as an alibi to move beyond a notion of tradition prone to regressive manipulation, and as a way of structuring my work. My use of history is not terribly self-conscious or academic. It is a way by which I bring multiple registers into my work.

HCOn 27 February 2002, a train was burned in Godhra, causing the death of 58 Hindu pilgrims and kar sevaks returning from Ayodhya. This is cited as the trigger for the 2002 Gujarat riots: three days of inter-communal violence in the western Indian state of Gujarat. Following this, there were months of violence in Ahmedabad, and further communal riots against minority Muslims for the next year. How did this affect your relationship with Kashmir?

NSWhen the Gujarat Riots happened—though I don't call them riots, I call it genocide—I was planning a very large and ambitious take on Kashmir, which had interested me for many years. When the 'riots' happened—when the notion of home became comparatively fragile—I felt that I was not able to gather my resources to do a very large work on Kashmir, but that I could sit quietly in a corner and read poetry and work on that. That's how I got so involved in reading the poetry of Agha Shahid Ali, a Kashmiri poet whose writing I had known prior to that, but only properly read at that time, sitting in my studio. I wanted to be led by the hand of this poet and enter Kashmir through him. That dark period in Baroda made me think not only of Kashmir differently, but of myself and location differently.

HCYou have many source materials, from Turkish, Persian, and Indian manuscript painting to the scroll and mural paintings of China and Japan, and the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish, Lal Ded, and Li Bai to the writings of Mirza Waheed, Salman Rushdie, and Chitralekha Zutshi.

NSThey jostle with each other.

HCMy favourite work by Darwish is Memory for Forgetfulness, which expresses sentiments similar to that which you just mentioned: all you can do is be in that moment. How do you feel about the relationship between your work and literature?

NSSometimes I feel that the best paintings in the world are illustrations. The paintings of the lives of Christ and Lord Krishna have interested and moved me very deeply. I have never had a prejudice against literature and painting connecting with each other, or being part of each other's contexts. But the reductive pedagogy of modernism was the norm when I was growing up into my own. Looking at examples of pre-modern painting, reading writers like Abanindranath Tagore, and being supported by the ideas of my mentors, including my husband Gulammoahmmed Sheikh, I learned that literature and painting need not impinge upon each other. No work worth its salt is threatened by its relationship with another form of art. This idea was enhanced when I was working in theatre. Initially, the actors were very reluctant to act in front of my painted backdrops because they thought something would be removed from their bodies. But I think that they then realised how much these contexts can facilitate expression.

HCHow do you pick the quotes that you integrate into your work?

NSThe first time I used text very consciously and deliberately was when I did the series 'When Champa Grew Up' in 1984. Much later, when I was doing a large set of works on Kashmir called 'Each Night Put Kashmir in Your Dreams', the paintings were hung like scrolls, and on the back of the canvases I inscribed a large amount of textual references. In a way, those references became my bibliography: my reading material. They were things I was reading while I was researching and making the series. Sometimes the text was related to the painted image on the front, sometimes only tangentially.

HCWhat does it feel like to inhabit your landscapes?

NSI got to know the land [of Kashmir] as a young person by walking. We used to go on treks across the valley and its mountains, often off the beaten track. At that time, the notion of trekking in the mountains for pleasure and discovery was not common, but we had friends who could guide us in the right direction, so we did it every summer. My mother was very interested in botany; she was a naturalist in many ways. This experience of seeing a world into which we could walk and discover became my first guide in my search for pictorial visualisation. The land became a frequent starting point for my work.

HCDo you see the landscape as a protagonist in your work?

NSNot only as a protagonist. There's an interchangeability with the characters. Sometimes the landscape is the protagonist and sometimes it reverses into becoming the mise-en-scène. It goes back and forth. I often shift the scale around when I paint. The landscape becomes contextual to the figure it is framing, or one figure might change in relation to another figure that is close to it. I find landscape a way of giving my characters autonomy, as well as connecting them.

HCThere are so many different kinds of feminism. I want to ask about yours. Since the showing of Four Women Artists, many things have changed in the world and in India. Has your idea of feminism changed?

NSI think it changes all the time. There are certain things that have happened that I did not understand back then. When I started painting and exhibiting I was in my mid-twenties. My husband—who was a little older than me—had taught me art history at art school. Our circle of friends contained a lot of male artists who were confident and fairly developed in the forms they were working in. Though we were all good friends, I felt my life was different to theirs. I had my first child a year after I was married, so I felt that my experiential world was different, and that I needed to portray that differently. I needed to develop a language for that. I didn't think I was making some kind of feminist statement at the time, but in retrospect I could perhaps refer to what I was doing as radical. At the time, there were complaints coming from senior artists about how I put my children into my paintings.

HCWhy not?

NSExactly! Those were the concretising moments for me. Doing the series 'When Champa Grew Up' was a very definite decision to work on a subject that had become a very pressing problem in our society: the brutalisation and torture of very young brides to extort more money from their families, often leading to murder. It was a phenomenon called dowry deaths. It was a time when a lot of information about it was coming out in the national press. It might have been rampant prior to that, but there had not been enough awareness. When I decided it was necessary for me to work on the topic, I was unsure how to do it. I needed to find the right language. It is one thing to want to work on something and another to find the language to say it, because you don't want to make what you're saying banal and trivialise the issue. You have to find the right way of talking about it. In that sense, the feminisation of my language has in some way contributed to my feminist ideas. It's not so separate from the language that I use.—[O]