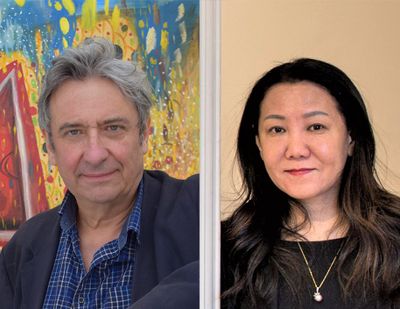

Andrew Stahl and Guo Xiaohui

Andrew Stahl. Courtesy the artist; Guo Xiaohui. Courtesy Malcolm Parks.

Andrew Stahl. Courtesy the artist; Guo Xiaohui. Courtesy Malcolm Parks.

The exhibition Beyond Boundaries at Somerset House in London (12 March–2 April 2019) marked the historic contributions of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing (CAFA) and the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, on the occasion of their 100th and 150th anniversaries, respectively. Spread across several rooms of Somerset House's 18th-century neoclassical West Wing, the exhibition brought together the work of 24 internationally acclaimed artists with close associations to these two significant institutions (Feng Mengbo, Geng Xue, Liu Xiaodong, Qiu Ting, Qiu Zhijie, Su Xinping, Sui Jianguo, Tang Hui, Wang Yuyang, Xu Bing, Yu Hong, Zhan Wang, Phyllida Barlow, Kate Bright, Susan Collins, Enrico David, Dryden Goodwin, Neil Jeffries, Lisa Milroy, Jayne Parker, Kieren Reed, Karin Ruggaber, Andrew Stahl, and Phoebe Unwin). Beyond Boundaries included painting, sculpture, installation, and moving image works, co-curated by CAFA's Guo Xiaohui and the Slade's head of undergraduate painting, Andrew Stahl, with artistic direction by Zhang Zikang, director of the CAFA Art Museum.

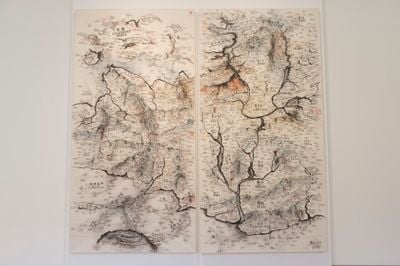

Though each institution is distinct in its history and context, the exhibited works share many formal interests and thematic concerns. Susan Collins' digitally constructed landscapes LAND, Jerusalem 25th November 2016 at 19.55pm and LAND, Jerusalem 7th November 2016 at 16.13pm (both 2017) share with Qiu Zhijie's imagined cartographies in ink an interest in both conceptual and concrete aspects of how geopolitical territories are formed over time. The subtly flowing and disappearing dancing figures in Yu Hong's hanging silk painting They Have Transformed Themselves (2018), like Phoebe Unwin's paintings Sweatshirt (2015), Head with Headphones (2015), and Building (2018) focus on the boundaries of figuration and abstraction, presence and absence. Meanwhile, an expressive use of material connects Phyllida Barlow's rough-hewn sculptures Untitled: brokenarch (2017–2018) and untitled: catch (2016) with Su Xinping's Wasteland No. 2 (2015)—an ambitious, sprawling graphite drawing of a landscape produced by subtly textured mark-making.

In this conversation, the exhibition's co-curators Guo Xiaohui and Andrew Stahl discuss the collaborative project's key ideas, CAFA's and the Slade's approaches to art education, as well as their own experience with the various forms of artistic and intellectual exchange—exhibitions, residencies, and formal study programmes—taking place between China and the United Kingdom.

The title, Beyond Boundaries, addresses the obvious geopolitical boundary between China and Britain. What other boundaries have you tried to address with this exhibition?

GX: The exhibition's title was suggested by the president of CAFA, Fan Di'an, and we thought it was perfect for the show. Beyond Boundaries marks a big celebration for both art schools—CAFA's centenary and the Slade's 150th anniversary. The exhibition is also about an exchange between cultures and celebrating these milestones together. With the explosion of information made possible by social media and new technology, we receive a lot of information and it feels like we face too much of it every day. I think it becomes critical to focus on how to select the information we need. I see technology as a new kind of barrier between how we relate to each other, culture, and reality. Historically, art has played an important role in bridging gaps, opening doors, and breaking limitations—and in this moment, it makes sense to have this exhibition given how globalisation has made conversations across cultures possible while making real, serious, and deep connection even more difficult.

AS: An important part of the age we live in is how quickly we can travel across the globe. It's not just email and social media that connects us, but the fact that we can easily visit different cultures physically and learn from each other and easily meet each other. It's extraordinary that all this physical work came over from China to be placed by the work of U.K.-based artists. A lot of the work in the show deals with the awkwardness, fragility, and subtlety of materiality, including the films. I think it's wonderful to bring the actual art together for this exhibition to ask questions. I liked the title Beyond Boundaries—it can also mean a vision beyond the normal or the imaginable.

How did you select the artists in the exhibition and who was involved in the process?

GX: Zhang Zikang and I worked together with the artist and curator Andrew Stahl from the Slade. We wanted to work with someone from the U.K. in order to have voices from both sides, but we also wanted a full collaboration so that we did not just focus on 'our side', or artists from our part of the world.

The approach to fine arts education in the two countries is very different. What are their respective characteristics and what role do these differences play in the exhibition?

GX: Yes, they are two very different systems. Art education in China is based on an old Soviet Union socialist model. It's quite different from the U.K.'s. From the 1990s, China went through some major changes and it saw a high rate of development in technology, including the introduction of the internet. At CAFA, the art education remained quite traditional, but the school also developed new programmes. For example, the recently established School of Experimental Art. It opened around five years ago, so it's quite new. Wang Yuyang and Qiu Zhijie are the heads of the school, which draws on older traditions while encouraging students to work with new media and technology. I think this interest in both old and new is reflected in the exhibition.

AS: The Slade is in some ways an argument about what contemporary art should be. We want to provide the critical framework to enable students to discover what is meaningful for them, to follow their own vision and conviction rather than tell them what to do. We encourage students to negotiate their way through the myriad possibilities by being exposed to the argument and discourse of contemporary art and art history. A crucial part of this process is the availability of ideas and possibilities using seminars, discussions, lectures, talks, exhibitions, workshops, and the feedback they receive on their practice as it develops, through both group and individual tutorials and the general studio culture generated by this forum of discussion.

Are there any plans for the schools to continue this dialogue subsequent to this exhibition?

GX: Yes, the exhibition is going to China in two years' time. CAFA has offered its museum, so we are working on getting funding for the British artists' work to be shown in China.

AS: As well as that wonderful opportunity that CAFA is providing, we hope to further academic collaborations, exchanges, and perhaps residencies—another important feature of art discourse today.

Could you tell us a bit about your respective careers and the interactions with China and the U.K. that have informed this exhibition and your practices more generally?

GX: I moved from China nine years ago and I took two MA courses at Goldsmiths. The first was Art & Politics, and the second was Cultural Studies. They both changed my perspective and gave me a wider view compared to before. I've also travelled around the world to see art, meet people, and learn. And my view has been that the West is yet to really understand the very best of Chinese contemporary art. For that reason, I'm interested in programmes and projects like Beyond Boundaries. I'm interested in bringing Chinese artists and their work here and taking artists from here and their work to China. I find this kind of exchange dynamic and invigorating.

AS: I have been to China a few times and have done residencies in many parts of Asia and Southeast Asia and I am aware of the wonderful way this experience can offer 'out of box thinking'. This has definitely affected my practice, which often focuses on the 'transcultural'. I am fascinated by different cultural discourses and how they can enrich each other.

During our tour of Beyond Boundaries, you mentioned that one of the Chinese artists in the exhibition is a former student of another artist in the show. What was your approach to curating in terms of generation and age?

GX: That's an interesting question. Actually, for the show's iteration in China, since we have a much bigger space we are thinking of bringing in more students from the Slade and from CAFA. We'll increase the artist list with students from both schools who have gone on to become notable artists. The Slade has produced many prominent artists lately, like Eddie Peake, Alvaro Barrington, Marianna Simnett, and quite a few CAFA students who have studied in the U.K.—like Lu Chao, who was one of Liu Xiaodong's students—have been gaining exposure. We are looking forward to bringing the show to China and involving an even younger generation of artists.

AS: Clearly CAFA has produced many wonderful artists—it is an amazing art school. The Slade selection does traverse a number of generations, but it focuses primarily on who is teaching there at the moment. I guess my list of whom the Slade has produced could include the three that Xiaohui mentions, along with many other young artists who are making their mark on the contemporary art scene in London. The previous generation also makes for amazing reading, for example: Cecily Brown, Martin Creed, Monster Chetwynd, Tacita Dean, Douglas Gordon, Mona Hatoum, and Rachel Whiteread. And the previous generation as well: Paula Rego and Nicholas Logsdail, the founder of Lisson Gallery, with whom Liu Xiaodong shows in London. I could go on forever, as every decade has produced many of the U.K.'s key artists.

Several of the Chinese artists had already worked and exhibited in the U.K., and the U.K. artists in China. Could you talk us through some of these existing connections?

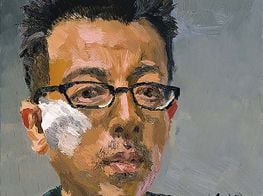

GX: Liu Xiaodong—who is one of the most prominent painters in China and in the world—made the paintings Egyptian Restaurant (2013), Egyptian Restaurant 7 (2013), Egyptian Restaurant 8 (2013), Two cups (2018), and Bananas and eggs (2018) here in London, where he is represented by Lisson Gallery. He often paints from life and the accompanying video in the exhibition, Half Street (2013)—directed by Sophie Fiennes—documents his time in London. One of the paintings was made on a street with large gatherings of immigrants, and another was made in an Egyptian restaurant. So there was already a connection to London and its many cultures.

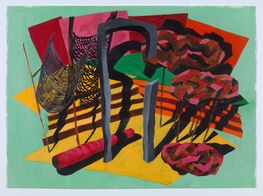

Andrew Stahl has spent time in Asia, and you can see the influence of these cultures in his painting, like the fan and symbols in Fan (2018). The video Seeing Hand (2017) by Dryden Goodwin is based on 1,000 drawings made as part of a collaboration between the artist and the cultural communities in the Chinese city of Xi'an.

AS: Lisa Milroy has also had a number of connections with China, and Kate Bright with Indonesia.

And some of the exhibited work looks beyond China and the U.K. altogether...

GX: Susan Collins' three photographs LAND, Jerusalem 7th November 2016 at 16.13pm, LAND, Jerusalem 25th November 2016 at 19.55pm and LAND, Jerusalem 28th December 2016 at 14.00pm of the West Bank—a part of the world connected to immense conflict—were taken automatically by a network camera over a period of months.

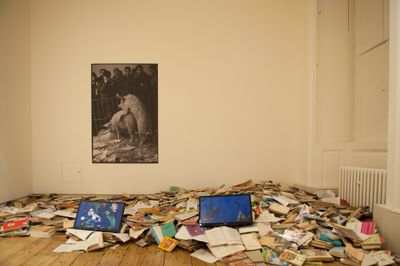

Xu Bing's A Case Study of Transference (1994/2018) was originally made in the early nineties while he was living in New York. I think of his work as a personal protest made out of frustration, anger, and anxiety from the difficulties of experiencing a different language and culture.

AS: As mentioned in the previous question, a number of the Slade artists, including myself, have done artist residencies in many countries. Looking beyond one's own cultural horizons for me has provided an amazingly rich challenge and lifelong connections with different cultures. I know that many of my colleagues feel the same. The question for me is: what do you do with this information and how do you learn from it and merge it with the culture you were raised in?

One of the central ideas is that of the artist-as-educator and art education more generally. Could you tell us more about this interest and the ways in which the exhibition approaches it?

GX: There is a tradition in China of artist-philosophers or artist-intellectuals and someone like Qiu Ting is part of this tradition. His work, made in the style of Song dynasty landscape artists, includes ink drawings accompanied by text based on ancient Chinese writing. This is in line with the idea of the artist being someone who not only makes images but one who formulates ideas in writing as well.

As well as being an internationally renowned artist, Phyllida Barlow is widely recognised for her important influence on a whole generation of artists through her teaching at the Slade, including former students such as Rachel Whiteread and Angela de la Cruz.

Also, someone like Sui Jianguo, CAFA's former head of sculpture, has made significant contributions to supporting art more broadly through his foundation in China. These artists have contributed to the arts in more ways than producing art; they've also played a role as educators and thinkers, helping to train and support younger generations of artists.

AS: I think what this exhibition demonstrates, partly through the quality and vivaciousness of the work on show, is that practicing artists play a crucial role in teaching art. Their excitement from their studio and their engagement with practice demonstrates to their students the excitement of contemporary art and being an artist. I think the range of work presented also illustrates the wonderful diversity of possible approaches and mediums available to young artists today in both schools.

Could you tell us about the process of putting the work of different artists together in this context?

GX: Many of the pairs emerged out of the formal affinities that the artists' works share. For example, the works of Phoebe Unwin, Sweatshirt (2015), Head with Headphones (2015), and Building (2018) work well together with Untitled #7 (weather) (2018) by the head of graduate sculpture at the Slade, Karin Ruggaber. Similarly, works by Jayne Parker and Lisa Milroy share a room and involve the relation between stillness and movement, creating a harmonious and intimate space for the viewer.

Wasteland No. 2 (2015) by CAFA's vice president Su Xinping is part of a 13-metre-long piece, but we couldn't include the entire work. His work has been paired with Phyllida Barlow's because the grainy surfaces of Barlow's sculptures look as though they were made from the textured grey earth of Su Xinping's landscapes in pencil. Both artists are also quite expressive in their use of their respective media.

AS: Certainly, the strong identity of the spaces and their physical features directed us in particular ways. For example, if there was a big ridge around the middle of the wall, we had to consider whether it was a suitable space to hang a painting. In fact, the beauty of the space and its strong identity helpfully limited the scope in a positive way and as Xiaohui says, some of the pairings were particularly successful and considered.

You've included some of Barlow's paintings in acrylic along with a great range of other kinds of painting. What are some of the approaches to painting adopted by the artists in the show?

GX: Yu Hong often paints female bodies as they grow, change, and transform. Her paintings comprise fabric dye on silk banners, but unlike previous installations, we have exhibited them without the weights at the bottom that stop them from moving. Instead, we've let them sway and move to evoke movement in the painted figures who are in gymnasium class. Yu Hong's technique is similar to traditional ink drawing where the artist cannot make changes and has to work decisively.

Tang Hui is the director of the Department of Mural Painting at CAFA. His work looks at collective and personal memory through the symbols and monuments of socialism. He often paints monuments reserved for leaders, but he makes the figures ordinary people. Tang Hui is also interested in Chinese traditional painting and Buddhist cave painting, both of which he combines with more modern painting techniques.

And there's Qiu Ting's Chinese ink calligraphy—a technique that is a lot like painting in its expressiveness. The piece was originally framed, but it was too difficult to ship with a frame. The artist was happy to hang it like an unstretched canvas and it looks quite contemporary in this state.

AS: There is a wide range of painting in the show, from the more realist paintings of Liu Xiaodong to the sensual paintings of Phoebe Unwin, which focus on figuration and absence but with hidden worlds of colour and feeling. From Su Xinping's beautiful and powerful flowing horizontal landscape pencil drawing, to Lisa Milroy's paintings, which reflect on the transformation of touch and the materiality of paint being transformed through both presence and absence into emotional and personal imagery. My paintings and sculptures reflect a slightly expressionist approach where the works carry the emotions and feeling of the artist, but also refer to the flowing of thoughts—things that can be identified. This is an influence from long Chinese scrolls, which you can walk alongside, finding and unpicking magical worlds. Similarly, Neil Jeffries treads on the boundaries between painting and sculpture with memorable and multi-layered wall pieces forged out of tin, while Kate Bright's vibrant Peony Tree (2019) has an intensity of colour and presence.

There's also a wide range of other kinds of mediums, from work using new media and technology to different kinds of craft. There's even a sculpture that began its life as an interactive piece. Could you talk us through some of these other approaches?

GX: Wang Yuyang's Breathe—Finance Department (2014) is a breathing replica of an office. The furniture in the installation has been fitted with devices that make each object's surface pulsate like a living body. It's an uncanny take on contemporary China's relationship to capitalism made by the School of Experimental Art's deputy dean.

The work of Zhan Wang is a series of 3D-printed sculptures based on the artist's reflection, captured over time. These sculptural impressions have been presented on plinths on which they rotate to give a constantly shifting view. The sculpture at the entrance by Sui Jianguo is also 3D-printed. With the help of 3D-printing technology, the details of a small clay sculpture have been magnified to emphasise the relationship between body, memory, and the object he created, which preserves—as a kind of handwriting—the artist's fingerprints and palm lines in the shape formed by his act of grasping at a fistful of clay.

Geng Xue was a student of Xu Bing's. She studied ceramics and used the medium to create the stop-motion video, Mr Sea (2014). Geng uses ceramics to craft a tale reminiscent of the stories found in the Qing dynasty collection of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio, merging storytelling with an exploration of the medium's visual language.

Enrico David is a well-known artist who taught at the Slade and he'll be representing Italy at this year's Venice Biennale. His works often engage traditional craft techniques. David's elegant but eccentric figures often involve a deep psychological meaning and a kind of inner fantasy.

Finally, Not Only Together (2019) is a sculpture by the head of the Slade, Kieren Reed, in collaboration with Abigail Hunt. It originates from an interactive sculpture presented at Tate Britain where the audience could manipulate the wooden pieces. Sadly, because of limited space, the version in Beyond Boundaries isn't interactive in the same way.

AS: An interesting feature of Wang Yuyang's office for me is that technology moves so fast that the office seems to become outdated. This is because it derives from office equipment from a few years ago and reflects on the speed of technological development. This may be incidental, but it gives the room a nostalgic twist as well as its brilliant breathing surprise. I wonder what it will look like in 100 years' time!

The work of Dryden Goodwin links drawing and film with a strong sense of place. It has wonderful echoes of memories, and the room he has created takes you to another place and time, as does the extraordinary film Mr. Sea (2014) by Geng Xue. Phyllida Barlow's work is often monumental and wonderfully full of unexpected awkwardness. Her smaller sculptures are presented precariously on stilts but have a beautiful materiality that links them to the work of Su Xingping.

For me, a key thing about Kieren Reed's installation was his delight in allowing his sons to assemble the piece, while still overseeing the process over the phone. It's this embracing of distance and creating a language and system of production that reminds me of Systems artists who used chance—dice throwing, and so on—to remove the artist's ego from decision-making. —[O]