Hilma af Klint: Back to a Future

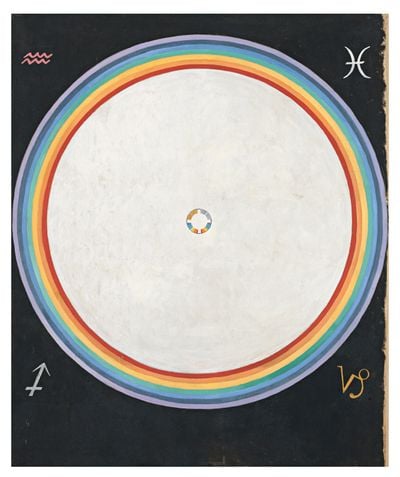

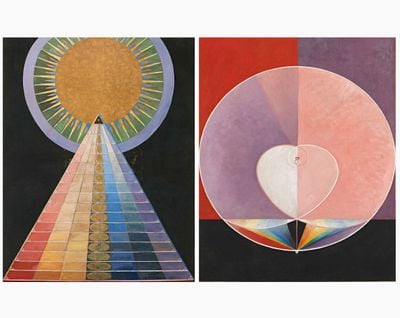

Left to right: Hilma af Klint, Group X, Altarpiece, No. 1 (1915); Group IX/UW; The dove No. 2 (1915). Courtesy the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photos: The Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden.

When Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at the age of 81, she left behind over 1,300 artworks—many of which she insisted could not be shown for 20 years after her passing—that have since expanded the canonical history of abstract painting in the Western world.

One hundred and twenty-nine of these works, among the 193 forming 'The Paintings for the Temple' cycle, are showing in Australia for the first time in Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), before travelling to New Zealand, where they will be on view at City Gallery Wellington between 4 December 2021 and 27 March 2022.

Created between 1906 and 1915, 'The Paintings for the Temple', which were the focus of an exhibition of the artist's work at Serpentine Galleries in London in 2016, marked a radical departure. Not only for af Klint as an accomplished realist painter—she graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1887 and sustained a studio practice in Stockholm—but for the legacy of European abstraction.

Af Klint's first forays into abstraction took place five years before Kandinsky created the first abstract picture in 1911; per Kandinsky's own written testimony, the original painting having been lost in the artist's move from Russia to Germany in 1921.1

The first of af Klint's abstracts—small canvases created between 1906 and 1907—comprise the earliest of seven series organising 'The Paintings for the Temple'.

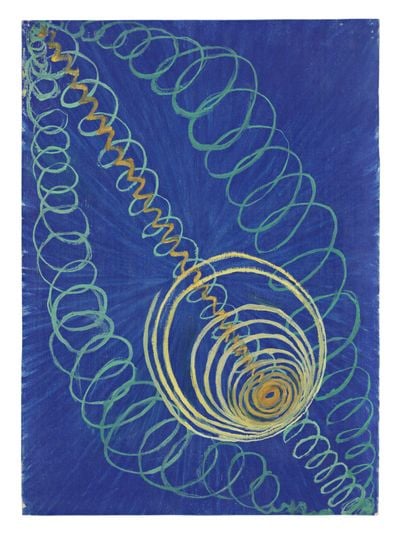

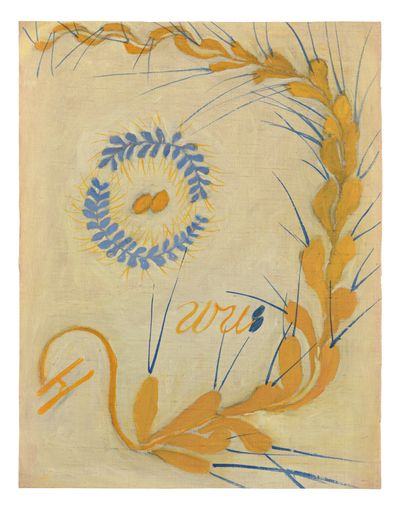

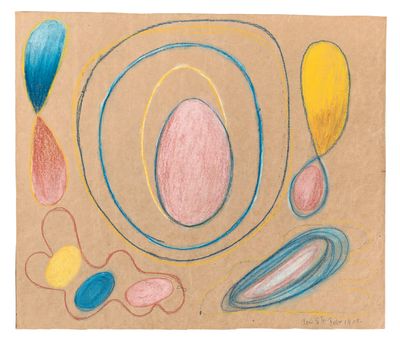

Collectively titled 'Primordial Chaos', the spiral, which af Klint used, filament like, to signify evolution, appears across diagrammatic compositions executed in shades of blue and yellow—the artist equated the former with femininity and the latter with masculinity—with green reflecting a synthesis of the two.

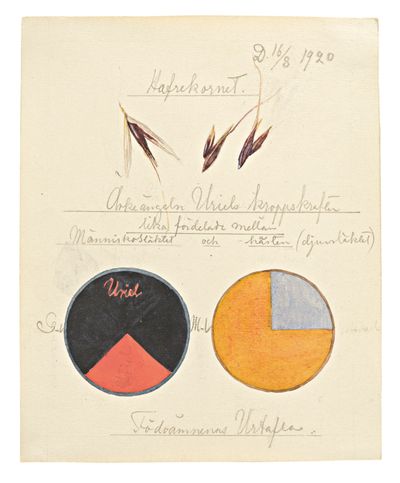

Cursive text appears across these works like energetic notations, pointing to another historical corrective. As curator Nicholas Chambers points out in the Secret Paintings catalogue, Marcel Duchamp and Picabia began to incorporate text into their paintings from 1913 onwards.2

In No. 19 (1906–1907), 'vus' appears, a word described by af Klint as 'darkness yet faith'; while in No. 5 and No. 7, the letters 'u' and 'w' appear, which af Klint defined as the spiritual world (U) and matter (W).3

'Primordial Chaos' speaks to af Klint's interest in scientific, technical, and philosophical innovations and publications of the time, from the founding of Theosophy in 1875 to the work of evolutionary scientist Charles Darwin and developments surrounding atomic theory, and there is a definite cultural throughline in her work.

The artist owned a copy of Theosophy co-founder Helena P. Blavatsky's 1888 publication The Secret Doctrine, the Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy, and was no doubt exposed to Charles Leadbeater and Annie Besant's publications Thought forms (1905) and Occult chemistry: a series of clairvoyant observations on the chemical elements (1908). As scholar Julia Voss points out, the Swedish translation of 'thought forms', tankeformer, appears throughout af Klint's notes.4

Amid these modern strides in scientific knowledge and spiritualist beliefs, af Klint sought to tap into the forces that compose the unseen world, merging scientific theories and observations of nature and spiritualism to create an abstraction rooted in a unique, organic vocabulary.

For many years, af Klint described her painting as 'mediumistic', and saw herself as a conduit for higher energies, not to mention spirit guides, High Masters, who actively instructed her. Between 1896 and 1908, she joined four other women to form The Five, who engaged in séances and automatic drawing and writing. In 1904, she joined the Theosophical Society, and in 1920 became a member of the breakaway Anthroposophical Society.

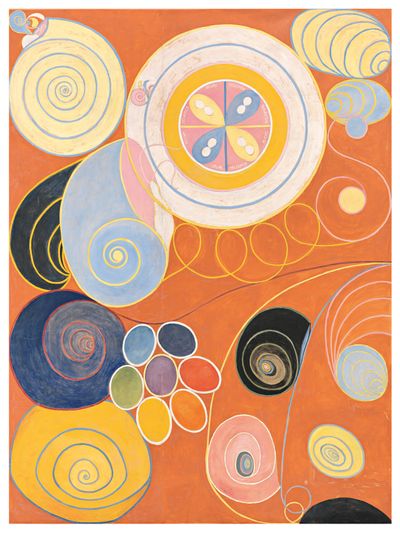

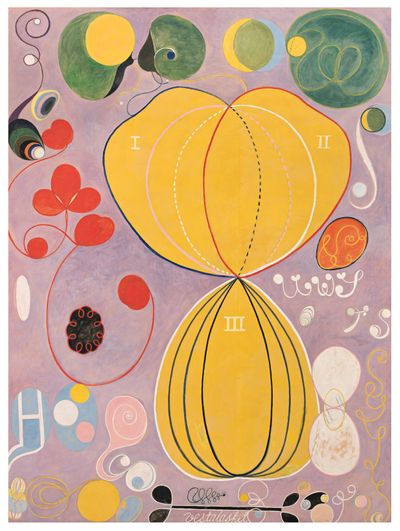

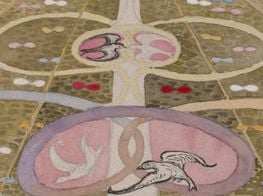

Af Klint's earthly cosmology is enshrined in 'The Ten Largest', a series of tempera on paper paintings mounted on canvas created between October and December 1907, just seven months after af Klint took the leap from realism to abstract representation.

It could be that the pull of this codex from the past, in which earth is rendered a universe unto itself, has more to do with persistent applicability than divination.

Monumental in size, these works, which af Klint described as 'evolutionary', chart the four stages of life—birth, youth, adulthood, and old age—using a fluid lexicon of organic shapes and lines that code the energy of existence into a naturalistic geometry.

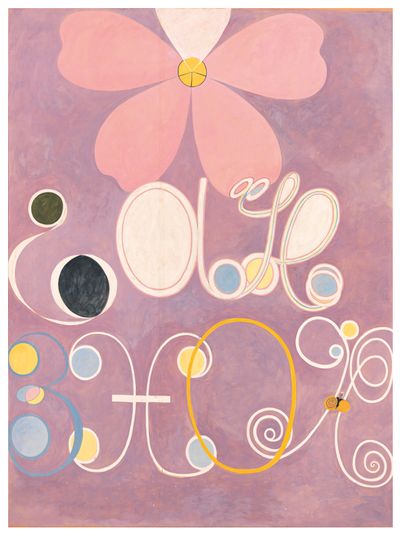

A large five-petalled flower blooms at the top of the canvas in No. 5, Adulthood (1907), below which cursive letters double as coiling vines, their negative spaces harbouring colours that pop out of a lavender dominion.

The artist's glossary offers frames of reference for the 'HoH' in view: 'to believe in a Spartan and loving manner', 'the wheat', 'Vestal and Ascetic', 'a time of work', and 'an image of good influences during the course of evolution'.5

Another influence in af Klint's journey to abstraction can be found in her family history, said to be composed of admirals, commanders, and cartographers from the 1700s on, including a grandfather responsible for charting the Sea atlas of Sweden.6

'It's tantalising to imagine the maps studied and created by af Klint's ancestors as a blueprint for her art practice,' writes Chambers: 'the combinations of image and text describe the physical world in a manner that can't be directly observed, just as af Klint's artworks chart a spiritual realm beyond the reach of our senses.'7 Take the solid and dashed lines in No. 7, Adulthood—at once a diagram and cartography.

Af Klint completed 'The Ten Largest' in 1908, returning to the studio in 1912 after spending four years caring for her blind mother, where she completed the final 82 works in 'The Paintings for the Temple' cycle in three years.

Among them are those composing 'The Swan' series. The first canvas of the group, The Swan, No. 1 (1914–1915), is divided by a horizontal line at which the beak and wing of a white and black swan meet like a yin-yang. The composition heralds earthbound ruminations on duality and synthesis that proceed as the series evolves into hard-edge abstraction. In The Swan, No. 17 (1915), for example, a circle against a red background is divided by thick lines of contrasting colour.

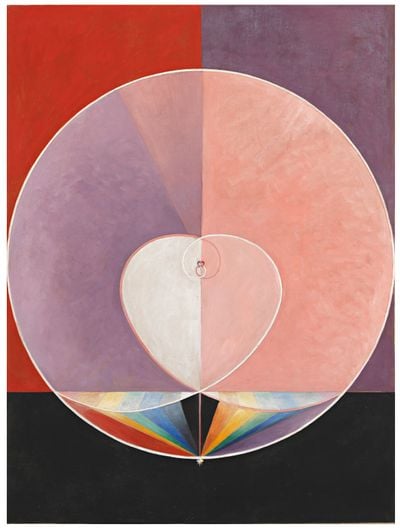

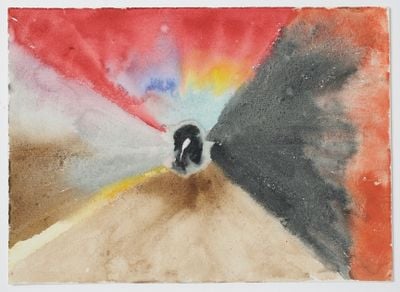

'The Paintings for the Temple' reach a striking crescendo in the final group, 'Altarpieces', created between October and December 1915. Three giant compositions comprising oil and metal leaf on canvas visualise thresholds into higher states of consciousness.

In Altarpiece, No. 1 (1915), a central lane divided into vertical lines of colour moves like a stairway to heaven from the bottom of the canvas up to its focal high point: a golden circle from which sharp rays are encapsulated by bands of earthy green and mauve.

It is said that af Klint's spirit guide Amaliel commissioned 'The Paintings for the Temple' during a séance with The Five in 1906—what af Klint would later call 'the one great task that I carried out in my lifetime.'8

Of the group, only Cornelia Cederberg agreed to assist af Klint on 'The Ten Largest'. The others were apparently worried that the scope of the project could lead to insanity; a fear that recalls a curse said to inflict lunacy on any sculptor who depicts the six realms of Samsara in Buddhist lore.

The line between madness and faith is indeed fine, as is the burden of belief when dealing with things yet proven. With hindsight, the sheer conviction with which af Klint viewed her 'experiments' as 'pioneering endeavours' that would 'awaken humanity' once 'they were cast upon the world' is an admirable demonstration of belief given the tepid response her work received in her lifetime.9

That conviction could easily have been misconstrued, or dismissed, even after af Klint's death. Before the Hilma af Klint Foundation collaborated with Moderna Museet in 2013 to stage the first in-depth af Klint retrospective, for example, the institution rejected an offer from af Klint's estate to receive her entire body of work. (Eventually, the foundation was established in 1972 by af Klint's nephew, Erik af Klint, to manage the artist's legacy.)

Titled A Pioneer of Abstraction, the 2013 exhibition hosted by Moderna Museet later travelled to the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, Museo Picasso Málaga, the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, and Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Norway. Moderna Museet presented an exhibition of the artist's work again between 4 April 2020 and 11 April 2021—the most recent exhibition to precede the staging in Sydney.

Within these showings are visions of the future, like a watercolour colourfield explosion from 1922; each work part of an artist's confident, and experimental trajectory.

In 2018, af Klint's insistence on keeping her work together, to be shown in a future time when the world would be ready to receive it, would result in a moment of startling affirmation, when the Guggenheim in New York staged a critically acclaimed exhibition of her paintings titled Paintings for the Future.

The museum's coiled form and white interiors echoed a design the artist sketched out in 1931 based on a prophecy from her spirit guide Georg in 1904: that 'The Paintings for the Temple' would be shown in a spiral-shaped temple with white walls. But, as former frieze editor Jennifer Higgie writes, 'this is perhaps less of a coincidence than it might initially seem'. Solomon R. Guggenheim's art advisor Hilla Rebay was a Theosophist, and asked Frank Lloyd Wright to design the museum as a temple.10

Even still, there remains a mystery in the work of af Klint. An enduring sense that this time capsule of what an artist heard, saw, and thought a century ago, has something to tell—and maybe challenge—those who view them now.

It could be that the pull of this codex from the past, in which earth is rendered a universe unto itself, has more to do with persistent applicability than divination. In 1919, af Klint described a time destroyed by war that created voids from which new ideas could emerge—that is, 'if there were sufficient faith in human imagination and the human capacity to develop higher forms.'11

There are traces of planetary thinking in af Klint's practice, as an artist who gave a cosmic bent to forms of post-representational universalist modernism that emerged around her in the 20th century. The invitation to connect endures. —[O]

1 Julia Voss, 'The first abstract artist? (And it's not Kandinsky)', 25 June 2019, Tate Etc., https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-27-spring-2013/first-abstract-artist-and-its-not-kandinsky

2 Nicholas Chambers, 'A wonderful linguistic system: Hilma af Klint's notebooks and text paintings', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.63.

3 Ibid.

4 Julia Voss, 'Hilma af Klint, painter and revolutionary mystic', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.43.

5 Nicholas Chambers, 'A wonderful linguistic system: Hilma af Klint's notebooks and text paintings', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.59.

6 Nicholas Chambers, 'A wonderful linguistic system: Hilma af Klint's notebooks and text paintings', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.55.

7 Ibid.

8 Sue Cramer, 'Hilma af Klint: The secret growing', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.23.

9 Sue Cramer, 'Hilma af Klint: The secret growing', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.22.

10 Jennifer Higgie, 'Becoming one again: The role of gender in the creation and reception of Hilma af Klint's art', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.69.

11 Julia Voss, 'Hilma af Klint, painter and revolutionary mystic', exhibition catalogue for Hilma af Klint: Secret Paintings, Art Gallery of New South Wales (12 June–19 September 2021), ed. Sue Cramer and Nicholas Chambers (2021): p.48.