Kim Tschang-Yeul: Art Without Ego

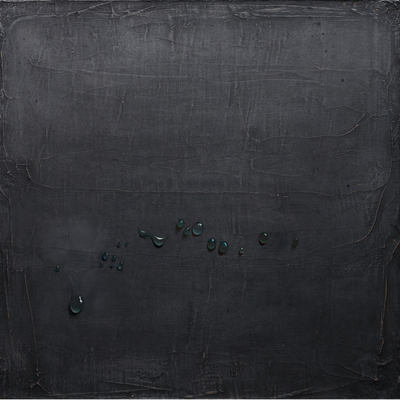

Kim Tschang-Yeul. Courtesy the artist.

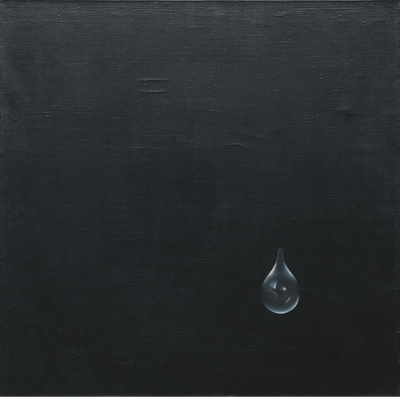

Kim Tschang-Yeul. Courtesy the artist.

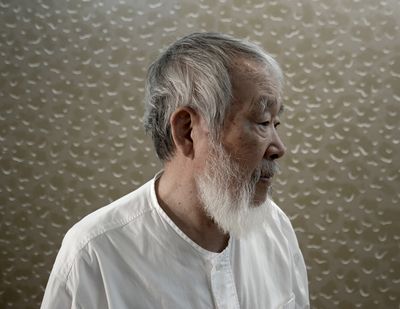

Kim Tschang-Yeul turns 90 this December, following an illustrious career that played a crucial role in bringing post-war Korean painting into the modern and contemporary art canon. Long celebrated for pensive depictions of water drops, the esteemed artist uses dual languages of abstraction and hyperrealism to articulate the psychological traumas inflicted by a tumultuous past. Last month, New York's Tina Kim Gallery unveiled its first solo exhibition of the artist's earlier works, titled New York to Paris (24 October–7 December 2019). The paintings on view provide a remarkable glimpse into a formative period marked by a transition from nonfigurative forms, and the debut of his signature water drops.

Understanding Kim's background is essential to grasping the meaning behind his contemplative paintings. Born in Maengsan, a town that is now in North Korea, the artist came of age in a historical time marred sequentially by Japanese occupation, communism, and civil war—the latter of which he witnessed from close range as a soldier. Following the war, Kim helped found the mid-1950s and early 1960s Korean Informel movement, which embraced abstraction as a turn away from traditional artistic norms. In 1965, a scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation enabled him to move to New York, where he became acquainted with the trends that pervaded mid-century American art. Kim, however, found New York inhospitable, and relocated to Paris in 1969.

The exhibition opens with a group of works created soon after this juncture in Kim's life. It comprises paintings wherein oozing forms protrude from various geometric configurations, and undulating lines wrap around nuclei of gradient circles. These compositions allude to the visual vocabularies of Minimalism and Op Art—most tellingly in the way that sparse backgrounds give way to swelling, ambiguous shapes; Kim fittingly referred to the canvases as 'paintings of the intestines', in light of their apparent biomorphism. The rippling of black and white lines also call to mind Op Art's play on ocular perception, acting as a precursor to the illusionist depictions of water drops that would define Kim's practice for over four decades to come.

An empty stretch of the gallery demarcates these earlier works from a pair of Kim's inaugural water drop paintings, first shown at Paris' Salon de Mai in 1970. Each featuring a magnified water drop on a stark canvas, the paintings' trompe l' oeil appearances belie a minimalist approach, in which gentle dabs of whites, blues, and greys are used to simulate translucence. The pair is followed by a succession of paintings created through to the early 1980s—some sparse, with others bearing tight clusters of droplets. In Il pleut (1973), tiny water drops slash across the surface of a wood veneer sheet. It directly references a concrete poem published by the avantgarde writer Guillaume Apollinaire in 1916, following his service in World War I. By replicating the poem, Kim paid homage to a Surrealist trailblazer who similarly lived through times of violent upheaval.

Although he has resided in Europe for the majority of his life, the artist infused his works with the Taoist principles of his upbringing, characterising water as an amorphous entity imbued with the power to dissolve and to purify. In working through the memories of a painful past, he found beauty in austerity, and solace in meditative repetition. Kim's pioneering approach to artmaking pushed abstract painting beyond its confines, and paved the way for new generations of artists working in an increasingly cosmopolitan world. In 2016, the Korean government erected a museum in his honour on the southern island of Jeju, to which he donated over 200 works from his archive. It stands as a testament to the important contributions that he made to 20th-century art, both in Korea and around the globe.

In this conversation, Kim discusses his beginnings in New York and Paris, early influences, and the formulation of his famed water drop paintings.

VCThe exhibition at Tina Kim Gallery begins with the paintings that you made in New York City, which feature spherical undulations and oozing forms. Aside from their biomorphic appearances, is there a reason why you refer to them as 'paintings of the intestines'?

KTYBefore coming to New York, I was involved in the Korean Informel movement, which was very much a reflection of my experiences during the war. I described some of my works as representing bodies run over by tanks—my work made in New York is a transformation of that.

VCWhat would you say were some of your key influences in developing your work during this period?

KTYWhen I came to New York all I seemed to see was Pop Art. Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol. I didn't really like Pop Art, but in retrospect I can see that it influenced me. In New York I felt estranged by the materialism of society and by the art that embodied this society. I did become friends with Nam June Paik during that time and seeing his first performances showed me how free you could be.

VCWhat compelled you to relocate to Paris and stay there for many decades?

KTYWhen I was a teenager, a teacher had told me that to become an artist, you had to learn French and go to France. That's what I ended up doing. I learned French before I learned English. Moving to France was not easy though. At that time, in 1969, all the artists were Marxist intellectuals. I didn't relate to them. I felt quite isolated. And then I met my wife Martine.

VCYou debuted the first water drop painting in 1970 at Paris' Salon de Mai. I've heard an anecdote shared by your son Oan Kim, but would love to hear it from you firsthand: how did you arrive at the initial impulse to paint water drops? How were the paintings received—both critically as well as by general viewers?

KTYI discovered the water drop one morning after working at night. Quite dissatisfied with myself, I had splashed some water with my hands on the back of the canvases. And I noticed that the water drops stayed there and were shining on the canvas. It was extraordinary. I thought: that's what I have to do. I wondered if I could make art out of this.

At that time, I wanted to break away from the experience of the war. When I discovered the water drop, I thought I had found a playing ground that could be my own. It also reconnected me back to eastern philosophies like Taoism and Zen Buddhism. My first show at Knoll International was very well received. Poet Alain Bosquet wrote a very good review in the newspaper Combat and a lot of people came, including Salvador Dali, who wrote in the guestbook, cela égale en magnificence la Gare de Perpignan—this equals in magnificence the train station of Perpignan!

VCOne of the things that I find most stunning about your work is the remarkable contrast between how they appear from a distance, versus up close. The water drops are hyperrealistic, but the brushstrokes become totally abstract once you approach the canvases. Did this technique come intuitively to you, or did it take some refining?

KTYAt first my approach was more hyperrealistic. Even though I was never interested in hyperrealism, I used an airbrush. But as time went by, I wanted to explore more of the possibilities that painting had to offer. My childhood hero, and the reason I became a painter, is Leonardo da Vinci.

VCThe exhibition wall text opens with a quote from Lao Tzu, the father of Taoism. It reads: 'The supreme goodness is like water / which favours everything and doesn't compete with anything.' Could you describe how—or to what extent—your paintings embody Taoist philosophy? What other philosophies influenced the development of your work?

KTYI've said often that painting water drops is a way of erasing my ego. This is an idea close to Taoism and Zen Buddhism. In the West, I feel that Marcel Duchamp and Dada came closest to these philosophies.

VCThere have been lots of writing and discussion about your artistic practice and adult life, but not much has been said about your childhood and adolescence. Were you interested in artmaking at an early age?

KTYWhen I was five years old, my grandfather started teaching me Chinese calligraphy. He kept praising me, so I kept practicing. I think that's how it all started. My uncle, who was a sort of mentor for me, also had reproductions of paintings by Millet and Monet on his wall. One day in the library, I read a book called The Lives of Great Men. Among them was Leonardo da Vinci. Reading about him made me realise that being an artist could be a great and noble thing.

VCIl pleut (1973) references a work by the avantgarde writer Guillaume Apollinaire, from his book of concrete poetry titled Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War 1913–1916. Although they are not included in this exhibition, the strategic use of words brings to mind your later paintings, which meld water drops with Chinese characters. Could you talk about the influence of Apollinaire's use of the written language in your work?

KTYApollinaire was a great poet. I used to write poetry myself and I published a few poems during the war while I was stationed in Jeju Island. I've used this poem several times as direct inspiration for my work. It is a very beautiful and metaphorical poem about the drops of rain, in a style he invented: the caligramme, which is a combination of calligraphy and ideogram—something I feel close to.

VCTo end with the present: the past years have witnessed a significant surge of interest in modern and contemporary Korean art, both globally and domestically, in which your work plays a role. How do you feel about this development?

KTYI always felt an inferiority complex towards Western art and culture. I feel proud that Korean artists whom in the past have greatly suffered and worked very hard, are finally getting some recognition. —[O]