Casablanca's Biennial Suffers Last-Minute Losses

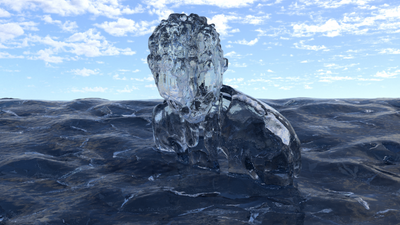

Héla Ammar, Bab B'har (The Door of the Sea) (2017). Courtesy the artist.

Casablanca is a city celebrated for its progressive modernist architecture. In 1917, it became the second city in the world after New York to adopt a comprehensive masterplan for its urban development. Today, this sprawling metropolis, the largest in Morocco, is viewed as 'a nexus of confluence for new international architecture and planning ideas that left a lasting mark in the city's physical and social fabric.' [1] Its coastal location as a gateway to both the African and European continents, no doubt formed a key point of consideration for the curatorial framework of the 4th International Biennial of Casablanca (27 October–2 December 2018).

Curated by UK-based art historian and curator Christine Eyene, the Biennial's title, Tales from Water Margins, references the The Water Margin—a 14th-century Chinese novel attributed to authors Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong. The story chronicles the prowess of outlaws operating from a marsh-edged mountain, using the 'in-betweenness' of the site to serve as both physical barrier and hideout in a battle against the tyranny of the Song dynasty.

The water margin serves as a metaphor for Eyene, who sees parallels with historical struggles, including the Maroon resistance that swept across the Caribbean and South America between the 17th and 18th centuries. Through an open call, 32 artists present projects across less than a dozen spaces located in proximity to the city's busy central intersection of Place des Nations Unies, including Villa des Arts, So Art Gallery, Thinkart, Instituto Cervantes, and San Buenaventura Church.

Overall, the ambition was to bring together relevant histories and contemporary responses to the natural borders between land and sea, including the relationship between current migrant crossings and the transatlantic slave trade, and the current global trend towards hardening national borders. Sadly, such broad curatorial intentions failed to fully deliver; the result—as admitted by the Biennial's organisational team during the press launch—of the last-minute loss of the Biennial's proposed public spaces due to inconclusive partnerships, including the central train station, Boulevard Felix Houphouët-Boigny, and Bab Marrakech.

This loss of exhibition venues led to a last-minute scramble to rehouse works elsewhere, creating the sense that the show was organised according to availability of space, which at times created a lack of cohesion. This resulted in a staggered unveiling of venues unfolded during the preview weekend in order to buy time to continue installing artworks, which meant that my experience of the show felt at once prescribed and incomplete, even if there are strong moments throughout.

The first space to open was Villa des Arts, a 1934 Art Deco villa run by the non-profit ONA foundation. Ibrahim Ahmed's South South (2016–2018) is located in the entrance hall: a sculptural representation for which Ahmed recast typical Cairo bricks from layers of textiles collected from all over the world. The work comments on the diversity of Cairo's Ard El-Lewa district, an area of the city which is currently home to many migrants and refugees who have brought with them many cultures. Raphaël Faon and Andres Salgado's computer-generated animation created from simulation algorithms, An Ocean of Memory (2018), is also on view in this space: at one point in the video loop, ghost-like bodies emerge out of the waters they then disappear back into.

The most rigorous and well-conceived presentation at this venue (and overall) is by London-based, Mauritian artist, Shiraz Bayjoo. Searching for Libertalia (2018) is a multimedia installation that relates to the artist's ongoing research into the legacies of European colonialism across the Indian Ocean region and beyond. Located in one of two adjacent rooms next to the entrance display, a two-channel looped video installation is arranged among vitrines and shelves filled with archive materials, photographs, and collages that include depictions of Sakalava royalty, sailors, and slaves in Ile Maurice, Dutch iconography, and general everyday scenes of colonial life, plus maps and lithographs dating to the 17th and 18th centuries. The video installation recounts three different stories that offer a point of entry into the history of Madagascar between the 17th and 19th centuries: Madagascar's struggle to 'liberate' itself from the Vichy administration; the free French army during World War II; and the story of Captain Mission, a character who appears in the book, A General History of Pyracy, supposedly attributed to author Daniel Defoe, in which 17th-century pirates were employed as fighters against European crowns. These histories intersect with Bayjoo's own psychogeographical approach to filming in Madagascar, where he retraced many of the sites from these accounts in order to present, in his view, 'a never-ending narrative of independence vs. unionism in the postcolonial story with reference to idealisms drawing from Negritude, Pan-Africanism and ultimately Fanon.'

On the first floor, rooms are dedicated to solo displays, one of which is Bosphorus (2011–2018), a film and sound installation by Magda Stawarska-Beavan and Joshua Horsley that focuses on Istanbul's infamous Strait as both a literal and metaphorical border between East and West. Next door, Cristiano Berti's installation Futile cycles Boggiano (2018) consists of a family tree and portraits: a snapshot of a larger research project into the name Boggiano, which could have links with an Italian immigrant who settled in Cuba at the end of the 18th century, and the slaves who worked on his coffee plantation.

Outside the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Casablanca, Thierry Geoffroy presents Emergency Room (2018): three tents emblazoned with graffitied text, such as 'BORDER BORDELLO,' placed outside the exhibition venue. During the preview, the artist held a 'critical run' around Daniel Buren's public sculpture D'une arche aux autres, travail in situ, Casablanca (2015), located nearby in the garden of the Sacred Heart Church—a critique of high-profile public art commissions in a city where its own Biennial received little governmental support. The school's entrance hall has been turned over to participating students from the school, with whom Geoffroy collaborated. Here, they express issues of social concern, from the urban experience to gender relations, by scribbling phrases across the walls in graffiti-style, including 'We Cannot Predict The Power of Waves', 'No Rush Equals No Stress', and 'Art Is Not Supposed to Be Beautiful, It's Supposed To Make You Feel Something'.

At GVCC, the oldest gallery in the country with a history rooted in presenting major works by Orientalist painters, the main rotunda space hosts a display centred on migratory flows and their influence on place. Drawing on the artist's French, Haitian and Italian roots, Raphaël Barontini's two medium-sized collage textile flags, presented alongside a sound piece by Mike Ladd, constitute Idole Déesse (2017), a striking reflection on the urban and cultural fabric of the Saint-Denis suburb in Paris. The flags depict fragmented classical, African bodies and masks against a cosmological background, fusing together disparate cultural heritages. The works are also a reflection on Barontini's view of his neighbourhood as 'a kind of assemblage of sorts that is always in transition, once associated with the French royal house, now working-class, multi-ethnic and creolised.'

Expanding on this sense of historical interconnectedness is Circulations I II III (2018), a new sculptural installation by Emo de Medeiros installed nearby, which includes 14 clay shields bearing the insignia of different army corps stationed in Africa during the Roman period, along with classic Sufi geometric motifs, thus traversing time periods and connecting histories across the Mediterranean and North Africa.

Aside from the main curated sections by Eyene, a mini-exhibition guest curated by New Zealand-based curator Ema Tavola is showing in the Arab League Park. Titled A Maternal Lens, the show includes artists Margaret Aull, Leilani Kake, Julia Mage'au Gray, Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai, and Vaimaila Urale. Installations, video works, and sculptures explore pacific bodies with artists who are mothers, with the aim to highlight the universality of motherhood, bring to the foreground contemporary debates on the labour of artists who are mothers, and connect Morocco to New Zealand through a collective cultural heritage of the cosmos from the Pacific Island nations of Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and Aotearoa New Zealand. The gesture, as with the exhibition as a whole, expresses the concept of the 'water margin' as a space where boundaries are blurred.

But despite the impact of the works on view and the expansive global perspective on offer, this edition of the Casablanca Biennial fell flat—an opinion that I underscore is based on my experience of the preview weekend and the disruptions that befell the institution, which have hopefully been resolved. That being said, most venues I visited felt accessible only to 'those in the know', with limited signposting and posters throughout the area that the Biennial is being staged, suggesting a general lack of interaction with the city at large; a missed opportunity, if not a victim of circumstance. —[O]

—

[1] For an overview of the history of urbanism in Casablanca, see Patrick Calmon de Carvalho Braga, The History and Legacies of Urbanism in Casablanca, Cornell Blog, http://blogs.cornell.edu/crp2000-modernity/2013/11/19/the-history-and-legacies-of-urbanism-in-casablanca/, published 19 November 2013.