Beyond the bounty: Art outside Frieze London

1:54 London. Courtesy of 1:54. © Victor Raison.

Art fairs and the press that circulates them thrive on inflated market value and sky-high prices, fostering an elitist environment

'Do you see a room full of white people?' the gallerist asked, checking if the headset projecting Jon Rafman's virtual reality world populated by pale figures was working properly. I was seated on an enormous faux snake at Seventeen Gallery's booth at Frieze in London, surrounded by swanky art collectors and dealers muttering six-figure prices into cell phones. 'Yes,' I answered, peering into the goggles. 'But that's what I saw before.'

Once again, Frieze London drew hoards of the financially advantaged to Regent's Park, filling out the sprawling tents and easing gallerists' post-Brexit nerves. And while articles in major publications over the past weeks have mused at the art shopping habits of the ultra-rich, one can't shake the feeling that all the noise was a distraction from much more critical concerns. My own unease was echoed by an oft-revisited suggestion that Frieze Magazine's own Dan Fox made in 2012: 'when half the world doesn't have clean drinking water, a show about "the crisis in painting" can seem pretty decadent'. So too, can a trade fair commodifying artistic ruminations on subjectivity, while not so far away, men, women and children drown while fleeing war-torn homes, and when those who do arrive on dry land face incarceration, separation from loved ones and systemic discrimination.

Elsewhere on the planet, police forces wrestle with racism, childish misogyny passes for politics, devastating natural disasters ravage homes, Haitians suffer from another devastating outbreak of cholera and political activists are banned from speaking freely. It all seems a little indulgent to gleefully gossip about sales of million dollar paintings or complain that the fair 'just doesn't have the same vibe it did last year'. To be sure, many of the seemingly innumerable works at the fair addressed politics and social concerns, (a new gallery section titled 'The Nineties' recreated 11 seminal exhibitions from the decade that championed identity politics) but in the end, every work on view was intended to be sold to someone with a thick wallet.

This isn't to say that art isn't a meaningful and relevant entity in the face of crisis, but money and institutionally engrained privilege in the art world can often seem to operate in isolation from real life. Thankfully, other happenings around London presented alternatives to the exclusionary narrative.

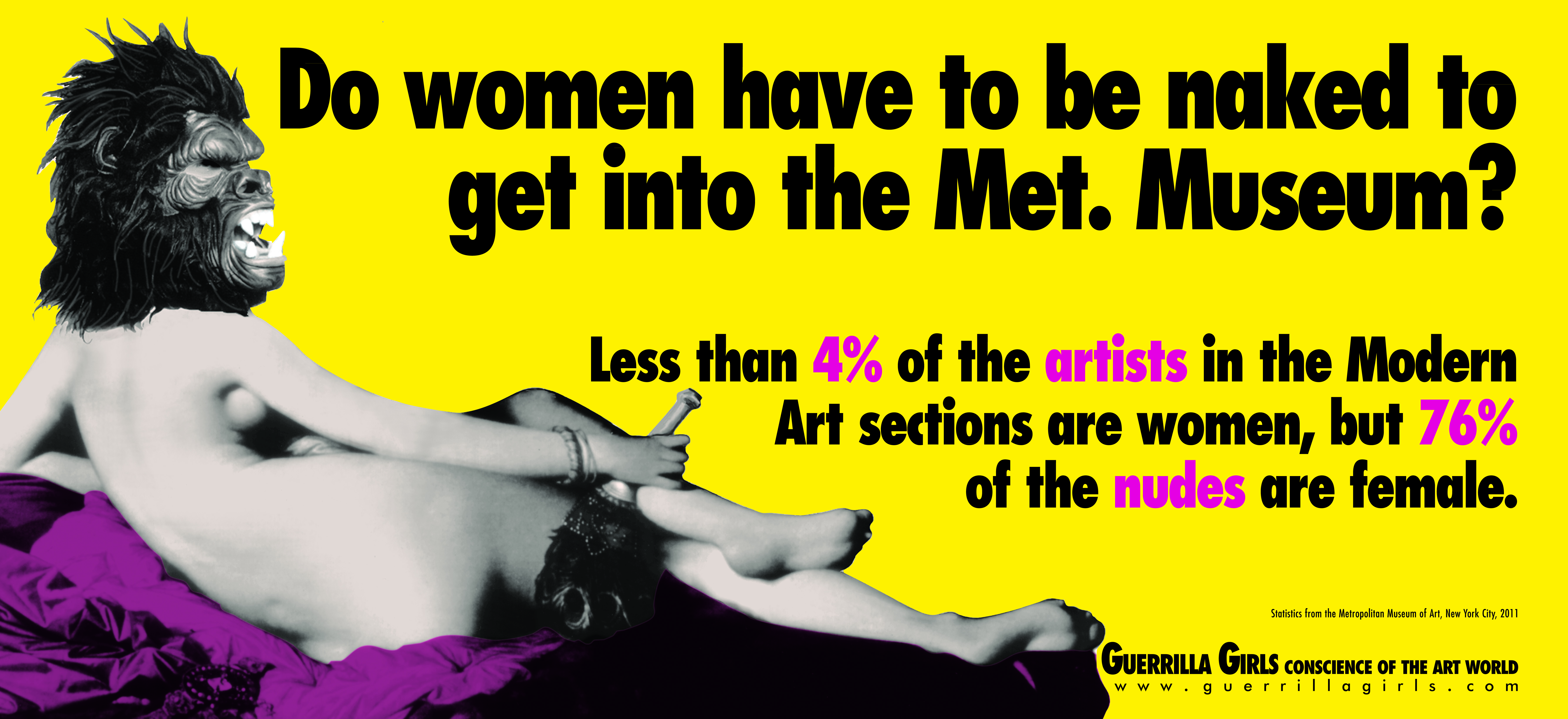

The Guerrilla Girls were in town for Frieze Week, revisiting their 1986 campaign Is it even worse in Europe? at Whitechapel Gallery (until 5 March 2017). Over the past 30 years, the group of anonymous feminist activists and artists have protested the pervasiveness of sexism in the art world, targeting museums, critics, dealers and collectors. In advance of their show at Whitechapel, the Guerrilla Girls sent surveys to nearly 400 European museums regarding the number of recently shown artists who are female or non-gender conforming, or hailing from Asia, Africa, South Asia and South America.

Some findings suggest moves in promising directions by directorial staff, though silences on behalf of institutions such as the Centre Pompidou, who in 2009–2011 staged Elles (27 May 2009–24 May 2010) an exhibition of art by women, point to possible 'tokenism'—a ticking off of the 'female show' without a real commitment to addressing imbalances. While only a quarter of the institutions answered the survey, the Guerrilla Girls have displayed a list of the non-responsive institutions on a large carpet on the floor.

During the fair, Guerrilla Girls also held a Complaints Department at the Tate Exchange (4–9 October 2016), at which visitors were invited to voice their criticisms about art, culture, politics and environmental issues. It's likely that they weren't in short supply; a survey by The Art Newspaper found that of all the solo shows on view in London this week, only 33% exhibited work by a woman.

Niklas Bartha of Bartha Contemporary, who did show two woman artists at their London space, noted that this was also reflected in the work on show at Frieze. Notably, the otherwise impressive exhibition Abstract Expressionism (until 2 January, 2017) at the Royal Academy of Arts featured an extensive hang of Eurocentric male artists such as Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt and Clyfford Still, with only a small handful of paintings by Joan Mitchell and Lee Krasner.

One of the most impactful exhibitions on view in London that week is untraditional in a number of ways: The Infinite Mix: Contemporary Sound and Image (until 4 December) is a tightly curated presentation in a former office building on The Strand—a temporary offsite space while the Hayward Gallery undergoes renovation.

Organised by Hayward director Ralph Rugoff, the show includes works by Martin Creed, Stan Douglas, Ugo Rondinone, Kahlil Joseph, Jeremy Deller & Cecilia Bengolea, Rachel Rose, Cameron Jamie, Elizabeth Price, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Cyprien Gaillard. Borrowing the languages of documentary filmmaking, music videos and theatre, the works deal with tumultuous cultural histories, social tensions through a combination of moving image, sound and music.

The venue is a far cry from sleek white cubes and fair booths: the building's stripped concrete architecture alludes to its utilitarian past and looks to be in a perpetual state of reconstruction. On the ground floor, Stan Douglas' video Luanda-Kinshasa (2013) (presented at Art Basel Unlimited in Basel this June) recreates a legendary 1970s New York recording studio, famous for propagating the 'then-current confluence of American jazz, funk and Afrobeat' made possibly by the emergence of African nations on an international stage.

Through the hallway, Ugo Rondinone's THANX 4 NOTHING (2015) is an immersive video installation featuring several screens showing beat poet John Giorno theatrically reflecting on sex, death and betrayal. Further on, Khalil Joseph's dual-screen video m.A.A.d. (2014) is a portrait of black neighbourhoods in Compton made by combining disparate visuals (home movies, news footage, his own cinematic imagery) with music from Kendrick Lamar's 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city. The result is a chilling rumination on inner city violence, poverty and power dynamics. Upstairs, Cameron Jamie's Massage the History (2007–9) features footage of young black men in Alabama performing hyper-erotic gyrating dances with bourgeoisie furniture in middle class homes—surely I wasn't the only one reading an unspoken undercurrent of 'fuck elitism'.

Downstairs, visitors walk through a dark parking garage and into a basement room to view Cyprien Gaillard's Nightlife (2015), a 3D film which focuses on a bombed sculpture in front of the Cleveland Museum of Art, wildly blowing trees in Los Angeles and fireworks over Berlin's Olympiastadion, set to a looped mix of Alton Ellis' Black Man's World (1970) and_Black Man's Pride_, a remake from the following year. One wanders out of the garage, struggling to recalibrate, emerging on a different street altogether than where one began.

Down the street at Somerset House, the fourth London edition of contemporary African art fair 1:54 was on view from 6–9 October 2016. With more affordable works and in a more intimate setting than other fairs, the event is less of an investment frenzy than an opportunity for interested collectors to encounter works by artists beyond the roster now expected at Eurocentric fairs. Founded by Touria El Glaoui in 2013, the fair holds biannual editions in London and New York.

Curated by Koyo Kouoh, the forum programme included talks by African and African diasporan practitioners who explore contemporary art, design, architecture and urbanism. While works ranged from photography to sculpture to painting, standouts include Nathalie Boutté's ink on Japanese paper painting_African choir VIII_ (2016) and Michele Mathison's Plot (2015), a grouping of steel and plaster sculptures in the configuration of a small corn field, a comment on the difficulties of subsistence survival during troubled economic times.

At the Tate Britain, the Turner Prize exhibition was on view. Every year, the Turner Prize is awarded to an artist under 50 born, living or working in Britain, for an outstanding presentation of their work in the previous year. While the winner won't be announced until 5 December, this year's shortlisted artists, Michael Dean, Anthea Hamilton, Helen Marten and Josephine Pryde, have recreated the works for which they were nominated.

The first room houses Helen Marten's byzantine assemblages of everyday objects, also on view at Serpentine Sackler Gallery. Marten's works take hours to unfold, overturning expectations of daily materials through their surprising amalgamations of material and form. In the second room, Anthea Hamilton's giant polystyrene sculpture of butt cheeks spread apart by a pair of hands is based off a 1970s proposal by late designer Gaetano Pesce for the entrance to a New York apartment. The piece has made waves through the press, as if giant assholes aren't getting enough attention these days. The piece is reminiscent of earlier projects including Aquarius (2010), storeys-high banner in a car park depicting a nearly-nude man between whose squatting legs visitors could walk. On the other side of the wall, an almost too-perfect digital blue wall leant an impossibly utopian background to hanging chastity belts—or were they children's swings?

Also on view were Josephine Pryde's six kitchen countertops, leaning against the wall like minimalist sculptures and printed with the negative forms of domestic objects. The shapes were exposed by sunlight in Athens, London and Berlin between the time of the artist's nomination and the opening of the exhibition, symbolising the impending end of easy mobility within Europe. In the centre of the room, Pryde's The New Media Express in a Temporary Siding (Baby Wants To Ride) is a model train, the carriages of which have been tagged by graffiti artists from the cities in which the work has previously been exhibited. For its iteration at the Tate Britain, the train is temporarily still, a state which The Guardian's Adrian Searle likened to a 'metaphor for Britain today, stalled in a siding ... a fun ride to nowhere.'

In the final room, Michael Dean's (United Kingdom poverty line for two adults and two children: twenty thousand four hundred and thirty six pounds sterling as published on 1st September 2016) (2016) is a room-filling installation with corrugated metal sheets and twisted abstract sculptures grouped together suggesting an urban wasteland. A gleaming copper heap in the centre of the room is a pile of pennies amounting to £20,436; it is the annual income for a family of four living on what the British government deems the national poverty line. For its iteration at the Tate, Dean has removed one penny from the pile, an ironic gesture towards the impossibility of maintaining a dignified quality of life for four on such a small sum. With it's ramshackle sculptures suggesting rundown neighbourhoods, the work is an anesthetisation of poverty, a monument to economic inequality. Much chatter suggests that Dean will be the likely winner of the prize. Interestingly, the reward for the Turner Prize is approximately £4,500 pounds more than his piece displays. In the hallway outside of the exhibition, a bulletin board invites visitors to write and post their comments about the show. Sentiments are mixed: referring to Dean's work, one visitor wrote 'How can we believe that 19.3 million people living in poverty in the 5th richest country in the world is acceptable?' while another scrawled 'YES FOR BRITISH ART, NO FOR RIDICULOUS ART, YES FOR BREXIT NOW, TOMORROW IS BETTER!'

Reminders of Brexit can be found all over the city. In his solo exhibition An Autumn Lexicon (29 September to 20 November 2016) at the Serpentine, Marc Camille Chaimowicz's installation Enough Tiranny (1972–2016) conveyed a sentiment common among Europeans today: with disco lights, discarded records and forgotten underwear littered across the floor of a dark room filled with the sound of dated rock n' roll music, the installation had the depressing vibe of a party that's ended. Britain seems to be suffering from the same hangover; the pound has plummeted, the future of trade and migration is unstable, and an uncomfortable air of xenophobia lingers. Things are even worse for refugees hoping for a chance at a new life in the UK. This year, Theresa May removed the post of minister for newly arrived Syrian refugees, lumping it in with a different office's duties while thousands are left in dire and immediate need.

In light of such troubled times, it should be mentioned that Frieze Magazine has published articles about the presumptive blow to international funding opportunities and decreased mobility for artists within Europe. Still, art fairs and the press that circulates them thrive on inflated market value and sky-high prices, fostering an elitist environment where a visitor is always ignored for a more important, richer, and more privileged patron. The bored and disinterested looks on the faces of the gallerists who are forced to interact with regular people reflect the true attitude of this art world: money talks, and there's likely no place more privy to such elitism than here. Even access to the tents on opening day are timed and tiered by wealth. Granted, all criticism must take into account that the fair is a trade exposition, the role of which is to ensure sales. Yet the question must be raised—can the magazine complain about socioeconomic uncertainty when its affiliate operates one of the most wealth-worshipping events in the country? —[O]