Catherine Sullivan

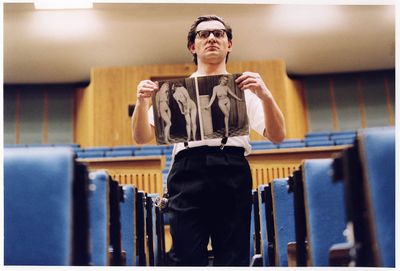

Catherine Sullivan. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

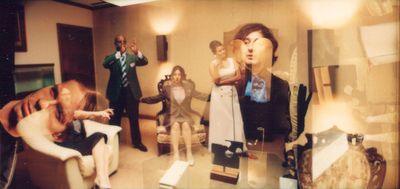

Catherine Sullivan. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Catherine Sullivan's artistic practice crosses genres and histories of art, theatre, movement, and performance, with poetry, literature, sound and popular culture, taking the actor as medium in the process. A former actor herself, Sullivan attended the California Institute of the Arts and the Art Center College of Design where she studied under Mike Kelley. To experience Sullivan's works is to become immersed in a visual composition made up of various performers, a range of cultural objects, social and political references, and plays of power that overlap and fold into one another with both appropriated and new gestures, symbols, and sounds that combine and permeate a new set of possibilities and questions. The compositions are saturated with historical connections and speculative visualisation.

Sullivan's art historical references mine specific avantgarde languages of movement and performance. Fluxus, Butoh—the form of dance theatre founded by Japanese choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata—and the legacies of artists such as John Cage, Joseph Beuys, and Yvonne Rainer meet with Jacobean drama, structured musical compositions, popular culture, and global political narratives that convey an uncertainty and awkwardness in their translations and obscurity. The two-channel video installation 'Tis Pity She's a Fluxus Whore (2003) fuses gestures and contexts, borrowing from events at the 1964 Festival of New Art at the Technical College of Aachen, Germany, where Beuys was attacked by his audience of students, and a 20th-century production of a 17th-century tragedy written by John Ford.

Themes of evolution, class, and the global economy come together in video installations like the The Chittendens (2005), with characters representing both the 19th-century leisure class and 20th-century middle management. The multi-channel video installation Triangle of Need (2007) involves various performers and collaborators, drawing on stichs from Edgar Allan Poe's poem 'Eulalie', along with a melody by Stephen Foster and a Neanderthal dialect, to formulate a non-linear dream-like journey along with the film's composer, Sean Griffin, questioning human progress in the process.

Sullivan's practice is acutely sensitive to intuition, and moves away from linear logic. Awareness is found in seemingly irrational gestures, sounds, symbols, and props that point to the register at which one could experience the work. The Startled Faction (a sensitivity training) (2018) debuted at Metro Pictures in New York (6 September–20 October 2018); it is a display of the artist's skill in orchestrating an elaborate polyphony of speech, movement, sound, costumes, location, cinematography, and editing styles. These are all synthesised into a series of scenes where a group of actors perform various office training exercises as a way to critically engage with the 'ambiguous labour' of women in the workplace—taking into account, for example, tasks often avoided by men, such as taking minutes of a meeting. Throughout The Startled Faction, Sullivan uses the soundtrack from Salt of the Earth: a 1954 American film based on true events and banned upon its release because it depicts a protest by Mexican-American workers at New Mexico's Empire Zinc Mine, for which women also joined the picket line.

In this conversation, Sullivan speaks about her practice and the making of The Startled Faction (a sensitivity training).

FKYour work allows for the experience of different spheres of existence and discourses by traversing cultural objects, history of art, socio-historical references or actual events, and products of ideology or normative power. These concepts and concerns overlap with one another and act in a polyphonic way. In addition, there are very specific art historical references, moments, and gestures in your work, such as the history of Fluxus and Butoh. How do you engage with and evolve these various genres, references, and systems?

CSThere are a lot of things in the world that I want to learn about, and projects usually start with that curiosity. Then I typically think in combinations of things that I think I know through direct experience or observation, and things that I haven't experienced directly but have concern for in the world. This usually converges with different trainings and pedagogies I've been influenced by in art, and the particular people I collaborate and create work with.

Things often come together in obscure ways that might not cohere with what is understood as relevant knowledge about a place, event, or reference, and for a long time I have been conflicted about that. I've thought it was important to allow myself to make work about things that I knew something and nothing about. The hope would be that my own knowledges are kind of conspicuous in the work, and distant concepts or experiences are over- and under-imagined with varying degrees of true understanding. I've always hoped that this problem resonated with the confusion, contradiction, and anxiety that exists within and around my concerns to begin with, and that treatments could be broad and obscure and still bear some relation to the gravity of the references.

I guess it's always been a kind of cautious and anxious process of giving myself permission to make mistakes in some regards, and to allow people to look at the work and maybe see those mistakes, question them, my voice, and therefore maybe anyone's voice or authority.

FKHow would you describe your role within the group dynamic when working with performers, actors, and collaborators to produce your video installations?

CSWhat I don't know is shared with everyone else in the work, and this causes unexpected things to happen, which I try to embrace and enjoy, because I know when I am editing there aren't any more shared decisions. It's different with every collaborator. I worked for many years with the composer Sean Griffin. He and I were in dialogue about the elements of the work, or just the kind of artistic space we were trying to create through the references. He would generally have his own workflow as a composer, with his own research and musicological interests, and I would work separately to build the mise-en-scène. We would then bring everything into rehearsals and would try to be open and responsive to each other and to what the performers would do with the work.

Over the years, I've come to work with more of the same performers. In every project there are always newcomers and 'legacy players' who play a huge role in developing the material. My dream would be to have a company where all of these people lived in a closely tied network with a more regulated work flow. But I would say the production model sadly is more along the lines of independent film, albeit with states and behaviours that have to be developed through a more intensive rehearsal process.

Many earlier projects were devised with the ensemble through improvisation and different kinds of scripts, along with Sean's musical scores. With The Startled Faction, I knew I wouldn't have the kind of time with the performers, so I wrote a screenplay hoping that it would make rehearsals as economical as possible. I've always recorded final 'settings' of the material in rehearsal, and in this case I actually used those recordings to compose without the actors there. There was no surplus of material, and while I missed the volume of possibility that comes from devising, it felt good that the actors had a sense of the whole project in advance.

I also owe a lot of thanks to cinematographer Raoul Germain, who has shot just about everything I've done. He's always been totally unafraid to try things and embrace different aesthetics in the work, sometimes within the same shot.

FKHow did you develop the script for The Startled Faction? Could you talk about the roles you constructed for your performers in relation to themes of identity, gender, labour, repetition, redaction, and withdrawal, which the work addresses?

CSIt was a case where I knew who I wanted to work with, precisely. I knew the work of the cast very well; some people I'd worked with before. So a lot of it was really driven by their presences and specialties and how that particular group of characters would read.

It isn't important that you know what character someone is playing, but more that you know what their function is or what they are coping with given the conceit of these lessons. Two of the characters have their pathologies reversed or mixed up and the other characters train and simulate. When I looked at the ensemble—the gender balance, and also the racial balance—I thought the characters could be perceived as a specific group of people with specific physicalities and motivations, but also as a random group.

What I liked about the impression of a random group is that, often in these sensitivity training scenarios, there's a kind of random feeling that comes from being with people you've just met or are going to spend a short amount of time with. In these one-off situations, you are asked to function as a group, thinking together. I find it productively estranged and intimate at the same time.

FKCollective power and transformation are recurring motifs in your work. I am very interested in hearing about how actors must transform in order to 'survive'?

CSI think I'm interested both in how actors are contagious and can conjure different kinds of space between people, and how acting is a means to see behaviours and habits in historical time. I am also intrigued by things like Elias Canetti's account of hysteria, mania, and melancholia as transformations that resist power or being eaten. Ironically, I had an acting teacher who compared acting to big game hunting, but I identified more with the creative flight of prey. The issue of survival is more about the problem of self-possession, compounded by convention and cultural style.

I've always thought that actors are in a unique position to make observations about culture because they reanimate what they absorb and embody tropes in peculiar ways; I've always been interested in style as something that binds some actors but sets others free.

FKHow have particular discursive genres like dance, academia, sociology, testimony, and social justice—and I'm pulling from The Startled Faction's description here—informed the work?

CSThere were a lot of direct conversations with women about their experiences, and other testimonies that came from reading comment threads in articles about women and labour. Some of this led me to discourses around emotional, invisible, and gendered labour. Arlie Hochschild's book The Managed Heart (1979) resonated with something I was calling 'ambiguous labour'—labour that leaks through the workplace often at the expense of women and people of colour. I had a long-standing interest in left-wing dance from the 1930s and choreographers like Anna Sokolow, Sophie Maslow, and Jane Dudley, who were explicitly concerned with workers' rights and engaged with their concerns through abstraction and dance aesthetics associated with that period.

I'm interested in the interaction between aesthetic and political motivations in art and how they sometimes obscure each other in productive ways. The Startled Faction simulates symptoms of ambiguous labour and develops them in terms of scale and visibility; sometimes it looks like dance. The female characters are coping with the cruel possibility of redaction and withdrawal to resist ambiguous labour, and the 'curriculum' in the sensitivity training is developed around those possibilities.

FKHow have you placed particular histories and their products together in The Startled Faction, and how do you bring to light various cultural issues in a language that is pointedly artistic? I also wonder how the legacy of European avantgarde theatre, dance, and performance fits as both a subject matter and mode of working in your practice in general.

CSI've always tried to locate the work in stylistic contradictions between modes of performance that are considered to be objective—and maybe in some sense, more politically viable—and artistic impulses that are highly theatricalised, my belief being that both are prone to convention. I've tried to look at this in terms of my own baggage, education, and preferences over the years, but I think people still hold assumptions about what political art should look like and how going deeper into the theatrical dimensions of representation threatens the political immediacy of artistic work.

I've tried to create space in The Startled Faction to test the viability of assumptions about how politics or social concern is transformed into art, and that has meant allowing influences that might be ideologically conflicting to play through each other. The gradual estrangement between visual art, performance art, and theatre in the 20th century always interested me as a symptom of an inherently troubled relationship between people performing and people watching them perform.

FKI am interested in your process of composition when working in a multi-channel installation format, which functions like expanded cinema.

CSThe multi-channel situations have been a way for me to give the viewer freedom to look at random things the way I do when I watch theatre. There are more frames to get distracted by and absorbed in based on what you might have an aversion to or interest in.

FKAlso, when developing the The Startled Faction, did the behaviour of participating performers transform what you initially set out to produce?

CSIn terms of scripting and composition, one challenge was the material I created with Cristal Sabbagh, who works in a Butoh milieu. She conjures specific physical states and her movement follows from deep concentration and absorption in them. It was a challenge to give her the necessary space and duration to create such movement and to stage it for the camera within the confines of what was supposed to happen in a given scene. She was totally responsive to modification, but there were so many great things coming out of the rehearsals when she could work in an open duration.

There was the problem of what had to be covered in terms of a script that also had dialogue. Movement forms which had their own internal structures had to be set with dialogue and the film's coverage of each scene. My previous approach was always to shoot in longer takes using a Steadicam, but there needed to be much more discipline in this case given time and resources.

FKThe work contains dramatic content set against imagery, sounds, and speech inscribed with sociopolitical histories. I'm thinking of the appearances of the Domino sugar bag, or the protest plaques that read, 'We are tired of living in debt'; there are references to gun ownership, and Indigeneity, too. The soundtrack seems to act as a set of instructions for the performers—it includes musical and audio excerpts of crowds, characters, and protesters from the film Salt of the Earth, and the repeated use of the song 'The Nitty Gritty' by Shirley Ellis.

Could you describe how these histories come into contact with one another, and how you resolve them, in an artwork that lives in the present?

CSI rely a lot on anachronism. There is one character in the film played by Zachary Nicol, who is conspicuously younger than the rest of the characters but brings in a lot of older references. He has a monologue written by Ira Gershwin called 'Modernistic Moe', which lampoons left-wing dance because its abstraction and modernity alienates the very masses it wants to reach. What you see in the film is this young, very contemporary looking man, speaking Ira Gershwin and getting behind it. He also initiates the dance sequence for 'The Nitty Gritty'__, which is a song from 1963. There's coherence in what he says given his function in the piece, but an incongruity in the sense that the youngest person is animating some of the oldest voices.

The 'curriculum' in the film also comes from the 1954 movie Salt of the Earth, and I created arrangements from the film's soundtrack. This becomes part of an overall texture populated by bodies that live in the present and animate voices and sounds of a contestation from the past that reminds us of unfinished business for the future. So, there's a kind of communion between the past and the present through the specific bodies of the performers, and hopefully this creates a unique space detailing a past and present that are highly relevant to one another. —[O]