At the 23rd Biennale of Sydney, Sustainability Is Action*

Leeroy New, Rhizome Colony (2017). Exhibition view: Wonderfruit Festival, Thailand (14–17 December 2017). Commissioned by Wonderfruit Festival, Thailand. © Wonderfruit Festival. Courtesy 23rd Sydney Biennale.

Before being deregistered 40 years ago, the Australian trade union the Builders Labourers Federation led a series of campaigns alongside community members to halt overbearing, environmentally unfriendly (or even ugly) urban developments that went against the wishes of those communities—like One Barangaroo, an enormous tower that opened as Sydney came out of a long lockdown.

Known more generically as crown casino (and majoritarily owned by Mariah Carey's ex fiancé, James Packer) the building overlooks the reformed sloping parkland of Barangaroo Reserve, a vertical dark apophyllite shaved down like Greenland ice.

This, rather than anything else, is my first impression I glean of the environs hosting Sydney's 23rd Biennale, rīvus (12 March–13 June 2022), presenting 330 artworks by 89 participants organised by artistic director José Roca with curators Paschal Daantos Berry, Anna Davis, Hannah Donnelly, and Talia Linz.

Envisioned as 'conceptual wetlands', the theme—rīvus translates to 'stream' in Latin—or themes, are salient. As I write this, Sydney meets the fifth month of El Niña. Each year, as if on queue, water becomes topical for good reason. Whether this reason is 'for the good of the population' is less certain.

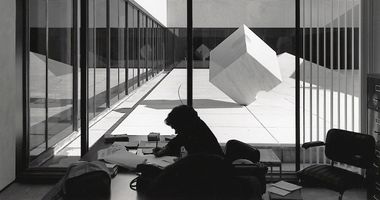

A viewer walking up to Stargazer Lawn at Barangaroo may pass Leaf Work (Derrigimlagh) (2020) by John Gerrard, an enormous six-square-metre reflective cube displaying virtual planes that stimulate real landscapes made with technology from the gaming industry—sensational, as if the enormous silver balls in the middle of Adelaide's Rundle Mall had a proximate older brother who studied 'abroad'.

At the Stargazer Lawn, The Great Animal Orchestra (2016) by Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists is housed inside a white and rectangular tent, as if hosted by Belgian chocolatiers, though it is actually sponsored by Fondation Cartier, which is from a different part of Europe.

Krause set out to do soundscape ecology in 1986, when the climate crisis was more Rachel Carson (think pesticides and Agent Orange) than Anne Carson (eschatology and mass extinction), and used his animal recordings to lure a humpback whale that accidentally entered San Francisco Bay back into the Atlantic Ocean.

With each change to a recording of a different habitat, the mood shifts explicitly.

Darkness blankets the interiors of the tent, save for light seeping narcotically from the entryways and iPhones—like that of the attendee to my right, inexplicably scrolling through Toyota images—and the spectrogram visuals to our front.

The 'animal orchestra' is made of field recordings and audiovisual representations of sonic footprints. The pitch and brevity of each animal sound is voluble; with each change to a recording of a different habitat, the mood shifts explicitly. Evoking either a Windows Media visualiser, a cardiogram, or an unhinged iVoice message from your last best friend, lines turn into print-like shapes—etchings, even—if you squint.

To see these musical patterns in the useful format of data is clarifying: the notes and pitch of birds like the red fox sparrow or the long-tailed jaeger are perfectly syncopated in the same way as a contemporary piece of music: played in common 3/4 or 6/8 time. Each beat has a point—hardly random.

The Biennale continues at the Walsh Bay Arts Precinct, originally the first site of commerce in Sydney, where the darkened antechamber suspended above water before Pier 2/3 contains Ghost Reef (2020–ongoing).

A collaboration between the Embassy of the North Sea and Xandra van der Eijk, several large, rectangular screens hang from the ceiling showing animated video collages of reef sections, hyper-close and reminiscent of perennial, herbaceous flowers. A nose away from the images, a view may become covered with the dappled light of nearby projectors, meeting an inspired frisson, as if daring viewers to do the predictable thing and take a selfie in the wall mirrors nearby.

This unlit antechamber functions like the mouth of a weir, carving open the way to the main body of the pier where afternoon light generously alights upon any work contained within. Slumber Party (2022) by the collective Casino Wake Up Time immediately singles itself out. The iron skeletons of four different antique single beds sans cloth or duvet are positioned upright, diagonally, so that their ends meet in the centre.

Casino Wake Up Time is a collective of Bundjalung and Kamilaroi women from the inland New South Wales town of Casino, which may explain why 'riparian zones, freshwater flow, kinship of plants and revitalisation of women's cultural weaving practices', imbibe the soul of the work—to quote the artists' statements.

Below this makeshift kiss of dormitory beds are a thoughtful miscellany of mats, adornments, and baskets weaved from native plants and weeds that came together, the artists say, over the course of the pandemic and its respective waves; specifically, the kinds that are well known for filtering detritus from rivers.

To the installation's immediate left, an ecological initiative by the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, Living Seawalls, displays a sequence of 3D-printed panels Untitled (2022), reflecting similar proofs, or ethics. Concrete shapes look to be nonagonal, at a glance, lined up and conjoined. Multiple fat screws drive their way through the bodies of each, further contemporising their rippled structures.

A video shows that these sculptures link together for practical reasons, as makeshift artificial habitats, or 'anthropogenic substrates', filmed underwater. Pictured in this footage, concealed cement forms are now enveloped with mosses. Fish with lunatic faces motion themselves in and alongside.

The seemingly waterlogged beams holding up the greater space of Pier 2/3, now softened by time or indifference, play friends to installations of great size in the main space. Hanging ascetically from these beams are patches of wool, cotton, and silk on cloths, inked with abstract black rubbings applied by the artist's community to seem abruptly interspatial, sewn and strung together.

The artist Aluaiy Kaumakan is from the Paridrayan Community of Pingtung County in southern Taiwan, affected by the destruction caused by Typhoon Morakot in 2009. The event affected streams of life through an annunciation of various physical facts. The devastation made a return home an impossibility for so many, but for the artist, the chance of revisiting in a more spectral sense was its own brief possibility.

In an alcove to the right of this work, hidden behind the kind of cloth that might suggest an enormous photobooth, a single-channel video by Hanna Tuulikki, Seals'kin (2022), shows Tuulikki singing to seals in a bay, before dressing herself in some kind of onesie, ostensibly meant to resemble them.

A sincere reference to Scottish folklorian rituals of grief, Seals'kin's very literal claims to 'mimesis'—as the brief patiently explains—falls just short of being affected. In a sense, this speaks to the axioms of the 23rd Sydney Biennale overall.

In its curatorial statement, rīvus points to the way a body of water could go so far as to litigate on behalf of itself, as per the concerns of a recent piece in The New Yorker, or the ways a forest in Appalachia might be 'granted rights'. A litany of rhetorical questions are whispered to the disembodied viewer. 'Can a river sue us over psychoactive sewage? Will oysters grow teeth in aquatic revenge? What do the eels think?'

This has the enjambment of a nice poem that could find a home in some literary journal. Nonetheless, questions seem posed without acknowledging that the hyperliberal language of human rights, so often prized by the Hillary Clintons of the world and used stickily here, have yet to adequately protect these ecosystems in a way that matters.

There are 'streams' that technically represent the few discernible lines of free-space snaking through this show, which collect and finish with the pronunciation of three works. Melissa Dubbin and Aaron S. Davidson's THE CLOUD IN THE OCEAN (2022) is a series of glass bulbs and tubes, some shaped like intestines, all connected to each other.

The tubes lead water upward, around, and below into a shallow bubbling tank of saline solution on the ground, simulating the transfer of heat from the ocean floor. Borosilicate glass blown by hand is neatly arranged to create its own network, the whole standing around nine-feet tall.

If the latter's logics are organic, Moré Moré (Leaky): Variations (2022) by Yuko Mohri to its left, hosts a series of unfortunate events—building, repairing, tinkering, edifying, levering, reusing, alleviating, and rerouting water. It is not, in its own way, coded as thinking.

An umbrella barely catches water that pours into a canvas bough strung to the ceiling that drips into a funnel before being carried upward through a transparent hose. A series of levers carry the water as if through the framework of a primary school scientific experiment while an invigilator stands to the side, motioning attendees away from stepping too close.

There's a reclamation going on here that is almost skeletal, with varying 'uncontrollable and nonhuman' elements cooperating, evoking kitsch as much as it does evaporation—a self-contained ecosystem within the larger, symbolic ecosystem of the Biennale. To quote a friend deliberately misquoting RuPaul, 'We, as gay people, get to choose our own biennial theses.'

If I've sounded uncharitable, I don't mean it. Care is threaded throughout rīvus and its assemblies of work that contemplate disaster while considering the soul inside disparate environmental forces that suspend it. 'Sustainability should be an action, not a theme,' a wall text states. It's hard not to agree, though the very best advice is rarely given to ourselves. —[O]