Kelly Akashi's Circle of Life Connects Body to Cosmos

Kelly Akashi's exhibition at François Ghebaly in Los Angeles, Faultline (5 November–4 December 2021), is a quiet derangement of mediums that colludes with the earth's physicality to aestheticise absent oppositions between life, death, and non-life.

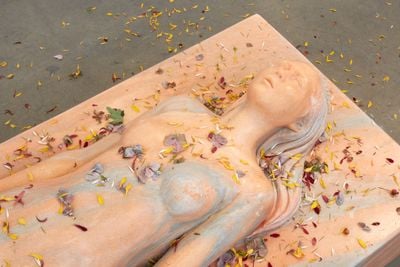

Kelly Akashi, Long Exposure (2021). Carved, polished, and waxed marble, plant matter. 81.5 x 184 x 76 cm. Exhibition view: Faultline, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles (5 November–4 December 2021). Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly.

The show begins in a room with vividly coloured photographic prints containing fine traces of crystalline structures. Akashi is an educated photographer, but these aren't quite photographs—she let crystals, which are not alive but certainly proliferate, grow themselves on film.

The images totally dement the expectation of two dimensions: trails of aggregation and involution create depth, hint at symmetry, and give way to lopsided tessellation. Geometries of motion promise further movement into details both like and unlike those which precede them.

The crystals look like they know what they're doing. The fractal singularity caught on film only one function of chaotic beauty's laughing participation in the routine elegance of math. Each print is called Formation, utterly distinct but properly named the same.

Dizzying as all that sounds, Six Beats of My Heart at the Scale of My Body (2021) grounds the viewer. An aluminium rendering of Akashi's measured heartbeat, it's a sculpture of a waveform, which is a picture of a pulse. Nearby, a webbed glass orb (Bloom, 2021) hangs from a bronze-cast hand.

Here, at the edge of the next room, emerges the unmistakable smell of something earthen. It's unclear what's emitting the scent, but its evocation of the dank margin between fertile and fetid feels appropriate to the space's lone visible artwork: Long Exposure (2021), a carved marble statue of Akashi's body.

The figure is prone, stiff, set in a block like a sarcophagus. Its appeal to death is not at odds with its life-like precision and the once-living flower petals scattered across it.

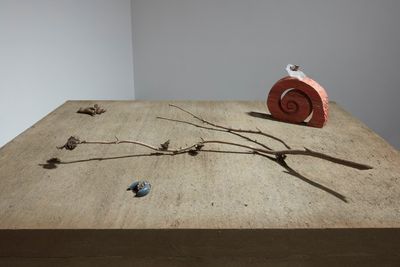

There is one more room, where it is evident that the muddy smell is coming from four enormous display pedestals made of compressed dirt. Dapples and cracks in sharply angled surfaces appear to release the aroma from well below the gallery's floor.

Objects sit atop the platforms: crystal hands with smooth edges, bronze hands with wrists ragged like ripped tendons, bronze tree branches—each called Witness (2021).

Some hands are ornamented with heirloom jewellery from Akashi's family, some proffer exactingly modelled sculptures of plantlife, some sprout plants from their flesh or emerge from stone. One poses a desert pinecone's needles like a spider, making pointed depressions on the pads of outstretched fingers.

A beeswax human torso pressed with thorny pieces of tumbleweed is called Heirloom (2021). Like the other desert botanicals in the room, the tumbleweed comes from Poston, Arizona, where Akashi's family was held captive because of their Japanese heritage in one of the United States' WWII-era concentration camps.

Akashi's work performs an always already existent alternative to the dualism of life versus death, and does so according to the specificity of her embodied self.

The press release for Faultline refers to mono no aware, the Japanese expression that is not quite adequately translated in such phrases as 'the pathos of things', or 'sensitivity to ephemerality'.

Akashi's work instantiates the concept with far more subtlety and rigour: not just a feeling to do with impermanence, but the sense that arises in the encounter between absolute flux and those aspects of its fleeting forms that come to self-consciousness.

It is the gentle gasp of the real as it affects its own nature with flashes of coherence, whether autopoetic crystal patterns or a knowing subject like the artist herself.

Physical and historical processes bear the universal whole and radical multiplicity at the same time and in the same space. The forces of the earth are the forces of the cosmos are the forces of history are the forces of a person; Akashi's work submits to and consigns the irreconcilability of these scalar fluctuations.

The art is indifferent to the linear passage through the gallery I describe—each artwork relates to all the artworks. The textures of the earthen platforms pronounce their detail as if familiar with the crystal prints. The beeswax figure echoes the marble, subject in their own ways to durability and decay; heirlooms signal generations of resemblances and divergences among selves.

The envisioned heartbeat recalls that nothing measured is inextricable from the character of its measuring apparatus, while any representation of the artist's individuated body both flattens and discloses the materiality through which she moves and from which she is distinguished.

Akashi's work performs an always already existent alternative to the dualism of life versus death, and does so according to the specificity of her embodied self. Her poetics dislocates scientific individualism and racist histories of power that depend on the disavowal of the ongoing differentiation of form by process.

Moving back through the gallery, the smell lingers, the flowers are a little more dead, and the prints continue to hang near the entrance that is now an exit. —[O]