S.E.A Focus 2023: When Patronage Becomes Form

In partnership with S.E.A. Focus

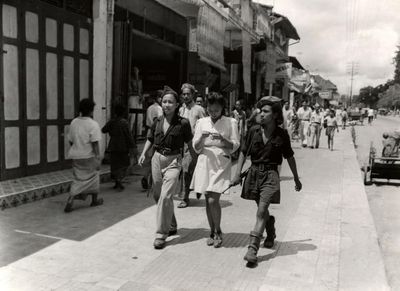

Left to right: Nathaniel Gunawan, Horikawa Lisa, Reuben Keehan, Margaret Wang. When Patronage Becomes Form: Who Is the 'Southeast Asian Collector'?, SEAspotlight Talks, S.E.A. Focus, Singapore (8 January 2023). Courtesy S.E.A. Focus.

Left to right: Nathaniel Gunawan, Horikawa Lisa, Reuben Keehan, Margaret Wang. When Patronage Becomes Form: Who Is the 'Southeast Asian Collector'?, SEAspotlight Talks, S.E.A. Focus, Singapore (8 January 2023). Courtesy S.E.A. Focus.

What does it mean to collect Southeast Asian art? How might a collection represent such a diverse region?

Through such questions, the S.E.A. Focus panel discussion 'When Patronage Becomes Form' sought out the unique positionality of the Southeast Asian collector.

Curated by Stephanie Bailey (Art Basel Hong Kong Conversations Curator), the panel discussion took place on 8 January 2023 and was part of the SEAspotlight talks hosted by S.E.A. Focus—an anchor event of Singapore Art Week and a cornerstone of the Southeast Asian art calendar.

Moderated by collector and art patron Margaret M Wang, the panel included Reuben Keehan, Horikawa Lisa, and Nathaniel Gunawan.

Keehan is the curator of contemporary Asian art at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) and has helped lead the curation of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) since 2012. Horikawa Lisa is the director of curatorial and collections at National Gallery Singapore (NGS) and was previously the curator of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. Gunawan is a prominent collector based in Singapore.

Prompted by insightful questions from Wang and the audience, the panel participants offered diverse local and international perspectives on curating a collection, including insights on the relationship between public and private and the impact of global aesthetics and geocultural frameworks on local structures.

The following text is edited and condensed from the answers provided by the panel in response to Wang's and the audience's questions during the live discussion, including Wang's invitation for the speakers to each introduce a work, artist or exhibit they have been particularly moved by. You can view the live discussion here.

Reuben Keehan on Artificially intelligent (2021) by Genevieve Chua

RKThis installation was featured in Brisbane's last Asia Pacific Triennial. Australia's borders were closed when the show opened. Queensland's state borders weren't open, so people from Sydney and Melbourne couldn't come. I was working with 25 artists; I had to work with every single one remotely.

Putting an exhibition together—particularly a large-scale production like this—is a lot of work. You can get exhausted in the lead-up when you need that energy. Normally, additional energy comes from working with the artists in the space. But in this case, I wasn't able to.

Genevieve had produced this beautiful work, and I could not have the joy of working with her in the space. Right now, I'm in Singapore working with STPI and Genevieve directly, installing her show in their Robertson Quay space. To connect with an artist again after three years—to work together in this space—has been so valuable.

What makes things energising for me is working with the artists. When we're working with collections, we're not just working with objects—we're working with their relationship to the artists, with different things that are coming into connection with each other.

Horikawa Lisa on the Rijksmuseum's REVOLUSI! exhibition (2022)

HLI have ongoing exhibition projects that deal with the transition from the colonial to post-independence period in Indonesia. As part of the research, I caught the REVOLUSI! exhibition at the Rijksmuseum last year. The exhibition was four years in the making, co-curated by two curators from Rijksmuseum and two others from Indonesia.

The exhibition tried to capture the experiences of the war for independence through different agencies and people who experienced the war, ranging from political leaders to ordinary citizens. The history is still fraught with painful memories for both Indonesia and the Netherlands.

The Rijksmuseum curators interwove artworks, photographic archives, sound, and objects, providing a visual palimpsest of sociopolitical history and the struggle for independence. As I prepare for my own exhibition, that strategy offers me a lot of food for thought. Another remarkable finding was the sheer scale of the materials related to Indonesia that are in Dutch institutional collections. One cannot help but question why and think about the possibility of connecting such collections more with discussions in examining the legacy of colonialism and the decolonising drive generated within Southeast Asia.

They had one room dedicated to fine art. Compared to the other rooms, I would say that this room had the least energy—maybe because of the difficulty in sourcing artworks from public collections in Indonesia, or perhaps it reflects the state of research on this historical period. That provided a lot for me to work on and was something quite exciting.

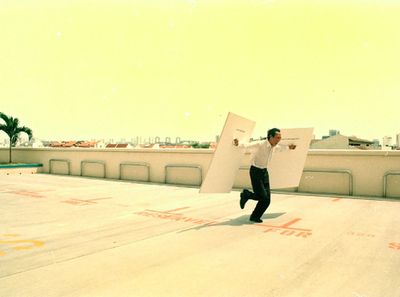

Nathaniel Gunawan on A Diasporic Mythology (2021) by Bagus Pandega

NGThe APT at QAGOMA was a highlight for me last year. I managed to catch it the last weekend, and I was stunned by this work.

I think it encapsulates what's so exciting, beguiling, and personal about Southeast Asian art for me. It looks very contemporary, but it plays a lot on the region's diversity and the whole Marvel Multiverse thing. It's a concurrent timing of Southeast Asia, what is constructed, and what's organic.

When you enter the installation, you walk into an orchestral performance. Pandega, a Japanese artist married to Kei Imazu, went to Tokyo and chanced upon a Taishogoto. It's kind of a forgotten instrument. He was fascinated by it, and it brought him to research forgotten Indonesian instruments and find notes they could make together.

As a visual centrepiece for the installation, he added tea plants to show the relationship between Japan and Asia. One of them pre-dates the occupation. The tea plant was brought by the Dutch from Japan to emulate the lucrative British-Indian tea trade.

We're dealing with so many layers. It made me realise that as a Southeast Asian, I'm also so mixed: Chinese by descent, grew up in Indonesia, my wife is Singaporean and part Indian. Seeing this experience encapsulated in an artwork against Brisbane's dynamic skyline was mind-blowing.

In the middle of the tea plant, he wanted to bring some contemporary humanity, so he added Indonesian performers' eyes. It's bringing a lot of things together.

On representing the diversity of Southeast Asia

RKSitting outside of Southeast Asia, our approach to coherently representing a heterogenous region is determined less by that regionality, a fairly recent construct that arose during the decolonial period, and more by proximity.

The APT has been presenting this kind of work since 1993. It sought to reconfigure Australia's cultural place from a regional perspective and reflect Australia's changing internal diversity. In the early editions, there was definite regionality. More recently, we've become interested in localities.

This idea of Southeast Asia is so firm within a geopolitical and a geocultural discourse that it has a material effect on the relationships between people. But there are other actualities, regionalities, and conceptions.

Of course, we have to recognise the overarching structures. This idea of Southeast Asia is so firm within a geopolitical and geocultural discourse that it has a material effect on the relationships between people. But there are other actualities, regionalities, and conceptions. We could talk about a whole range of historical matrices.

We try not to impose these structures on it. Within our Asia-Pacific department, we have curators of Asian art and curators of Pacific art, but increasingly we're finding that even that boundary is porous. If we look at linguistic and cultural links throughout the region, much deeper relationships can be examined within an exhibition or collection.

HLI struggle with the constraint of approaching Asia from an outsider's perspective, which has been prevalent in Japan. This concerns how the concept of "Asia" has been historically constructed and approached in Japan. My desire to approach the region's art from a different perspective prompted me to come to Singapore.

Even though we're a relatively new museum, the National Gallery's collection houses over 8,000 works spanning the 19th century to the present. Our collection started in 1960 with a personal gift of over 110 artworks from philanthropist Dato Loke Wan Tho from his collection, at a time when there were no national-level art museums in Singapore.

Our responsibility lies in destabilising the various fixed perspectives about what constitutes the country/region towards transnational and comparative narratives that go beyond that.

He hoped that one day his collection would be featured in a museum. The works he donated already included those from the region, works by Indonesian and Malayan artists. We are in a very interesting position—to present the art histories of various regional contexts through their connections or disparities.

We embrace the incongruity of the artistic production in the region. It's part of why you rarely see us doing a country-specific exhibition at the gallery. The Raden Saleh is presented alongside Juan Luna, or the history of Minimalism is viewed from a regional scope along with wider contexts.

Our responsibility lies in destabilising the various fixed perspectives about what constitutes the country/region towards transnational and comparative narratives that go beyond that.

On the process of selecting artworks and curating a collection

HLIt's very rare that I go to an art fair and find works to collect for an institution. It is a collective decision-making process. Every curator starts by preparing a proposal; the research involved in this process is very extensive.

The significance and acquisition price of artwork must be justified. Much discussion also takes place on how the institution will use these works for research and exhibition—we cannot spend public money for the works just to be stored away.

The extensive research that takes place in the pre-acquisition stage, including its provenance (where has the work travelled over the years?), has not been made public to date. Institutions like ours need to keep exploring ways to make that more transparent to the public.

RKWe do much the same. In addition to the object itself, there are rationales based on how something fits into the collection. We run through potential scenarios for collection-based exhibitions the object could fit within.

If it's an artist we hold in depth, we might think about the narrative of their practice or a particular context they're operating in that might be profiled. We might think about dialogues across media with other works in the collection or conceptual relationships. I enjoy that process as much as the research into the artist or the work itself.

In the last few years in Australia, provenance research has become a major factor. It's conceivable that we could be forced to decline very generous gifts if certain periods of provenance can't be established because objects are circulating that have been stolen or plundered.

It's imperative that one of the first things you do when visiting a place that you haven't been before is to look to the historical work and the way the practices developed to this point.

Working within an Anglo-Celtic institution in Australia, I always return to the APT's founding principles. One of those was not to use our aesthetic frameworks. Understanding how an artist's practice functions in its context is important.

I don't want to be one of those people with a European art history degree who uses that aesthetic framework to determine what I do in another part of the world, misrepresenting what's happening. Before specialist curators came into the picture, the APT would partner an institutional curator with somebody who really knew the context. In the dialogue between them, the work could be understood in a more nuanced way.

It's imperative that one of the first things you do when visiting a place that you haven't been to before is to look at the historical work and the way the practices developed to this point before deciding what to include in a collection. This is how to participate in a dialogue with the place.

On partnering with artists and developing relationships within and around a collection

NGI've been collecting for almost ten years since returning to Indonesia. My methods are more rudimentary than museum archiving and provenance. But people forget that managing—contemporary Southeast Asian art especially—is like walking blindfolded in a jungle.

I find it hard to believe someone who says this is a living artist's best phase. They're still producing work, sharpening their practice. How can you say it's their best? Unless you look to the market, which is an easier guide but not very fascinating. After a few years, I realised the works, as Reuben said, have to speak to each other.

Collecting contemporary art is a journey without an endpoint established. We are growing up with the artists, the galleries, the ecosystem. That's part of the satisfaction.

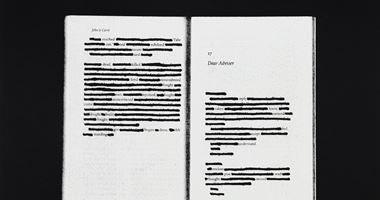

My collection is very rojak, all over the place. But I'm starting to find red threads—little satisfaction. The claustrophobia of one of Heman Chong's calendar paintings, 1984, led me to Oscar Muñoz's exploration of 1984, which has the same claustrophobia in the Latin American context.

I hang it next to Eko Nugroho, Indonesian reformists, political claustrophobes. It works. They speak to each other. I've gotten a few subplots like that; it's still developing. I like to think there's a long way to go in collecting, but the discoveries help. I try to write at least a paragraph about each work I've acquired as a personal archive on what attracted me to it.

Collecting contemporary art is a journey without an endpoint established. We are growing up with the artists, the galleries, and the ecosystem. That's part of the satisfaction. It also helps to speak with collectors with the same sentiments and impulses. It's a makeshift effort.

HLThe material produced while the work is being acquired can become of historical interest. I've seen wonderful exhibitions of one object with a massive paper trail. It's a valuable part of social and cultural history—an insight into what people were thinking.

During my first research trip for the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, I found photos of the curators in their underwear, in hotel rooms, and sleeping on planes. It's an incredible addition. Kuroda Raiji—the chief curator—also showed me his VHS archives.

There was documentation of performances by Southeast Asian artists in the 1990s in Fukuoka, where many things were happening. Open City Tenjin, a biennial commission of ephemeral pieces, was in the city, and so was the fourth Asian Art Show.

In addition to the performance documentation, Kuroda left the camera on for the events' combined artist party. It's interesting to see the network in the room. Lee Wen, Navin Rawanchaikul, Masato Nakamura, Mona Hatoum. There's a whole range of people.

It's a legendary video, a moment of history. Nakamura-san and Navin created exchanges. Lee Wen went and joined command N with Nakamura-san. Nakamura-san showed at Taxi, Navin's gallery space. We're collecting objects, but we also collect ephemera, moments, and oral histories. Integrating them into exhibition-making is exciting.

It brings history to life in the same way that an artist-run exhibition, a guerrilla performance, or an opening where everybody's in the same room can make us feel. It was exciting then and needs to excite a new audience as well.

On the impacts of local private collections and foreign frameworks on public collections of Southeast Asian art

HLCaroline Turner said in the nineties that we've come a long way. Our team of curators have been building on the work done by regional and international scholars to look at art histories from various angles that extend beyond Euro-American referential frameworks.

We have ten members in the Acquisition Committee, all of whom are external specialists comprising art historians, curators, artists, and collectors. We are mindful of having our committee's perspectives be as diverse as possible—the gender ratio, the countries of specialisation, each with their respective contextual backgrounds. They help us approve acquisition proposals and provide objective layers in the review process.

The challenge lies in making visible a public collection's value: the research it can generate, the new discourses that can be produced, and safeguarding care and conservation of artwork.

Private collectors and private museums in the region have a critical role in constructing art histories and providing space for art and collections. We work closely with private collectors. Sometimes, given that many modern artists in my field carry national significance in their respective contexts, it can be challenging to seek support from private collectors to release their works to a national institution in Singapore.

The challenge lies in making a public collection's value visible: the research it can generate, the new discourses that can be produced, and safeguarding care and conservation of artwork. I must admit that occasionally, I wonder if the conventional, historical practice of Singapore institutions collecting regional artworks is sustainable and whether it can benefit from re-thinking. Perhaps some ways are yet to be explored in sharing knowledge and even co-partnership with regional institutions in collecting works from the region. I do not have an answer or solution for this now, but I do dream about this.

On rationality and irrationality in gathering and presenting a collection

NGIf you don't know the history of an artwork, it just becomes a venerated object. At the same time, thematic or emotional shows can balance it out. I think it's also necessary to bring up diverse experiences, not as a politically correct thing, but for different emotions. Emotions have been subjugated under irrationality in art, but even as spectators, they hold some importance.

Collecting regional artists is a necessity. If we don't, who's going to do it? One forgets that artists are living, working people. They have families. It's their livelihood. You can't divorce that from their practice.

Collecting regional artists is a necessity. If we don't, who's going to do it? One forgets that artists are living, working people. They have families. It's their livelihood. You can't divorce that from their practice. I like getting to know them, and I have a responsibility.

That's why it's all about context. It is strange that people collect an Amoako Boafo and just put it in front of their console. But if you put it against Bagus Pandega, and they talk about diaspora, that's interesting, a dialogue. The context will support the object beyond its luxury or market value.

RKThe process that Lisa and I have been talking about is not necessarily rational, but it is a rationalising process. It's how we take all of the research and the reflexivity that can go into engaging with artists' practices and allow for this element of intuitive response.

This is the thrill, the singing of the work. Like Bagus's work—when you see this cacophony in the space and things moving. All these crazy things are going on in the work; they hit you at a level you don't immediately rationalise.

We smuggle this little kernel of irrationality into the institution. We can contextualise the work, but it's important to maintain its spirit, then lie in wait for someone to have the experience.

The museum will rationalise it for you. There are registration and conservation professionals who look after the work. There are dedicated floor staff who protect the work and talk with visitors. Our finance team reports to the trustees, who report to the government that we are acquitting our funding responsibly.

Then somebody out there will see the work and have a profound emotional response to it—laughter, rage, tears. We smuggle this little kernel of irrationality into the institution. We can contextualise the work, but it's important to maintain its spirit and then lie in wait for someone to have the experience.

HLIn recent years, we have seen new acquisition proposals that may not neatly fit into the Gallery's conventional collecting focus—for example, works that fall in between fine art and craft categories or seemingly traditional objects that signify engagement with modernity. The approving authority could see it as incongruent. But it reflects how our thinking is developing. Room to expand with a seemingly incongruent approach provides the institution energy for renewal and rethinking.

On emergent themes and motifs, and hopes for the future

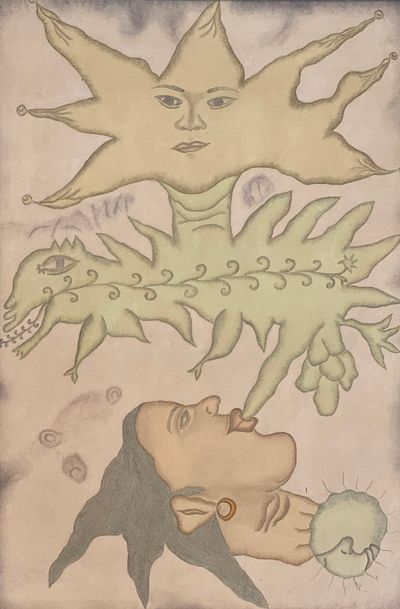

NGOne theme is rediscovery—rediscovering hidden narratives or artists on the fringes. Last year was really good for I Gusti Ayu Kadek (IGAK) Murniasih from Indonesia. She's a self-taught artist. She does very fantastical, grotesque, bodily, and bright paintings.

Imagine if this was shown 20 years ago. In Indonesia, the gallery would have been shut. But now it's shown in Gajah Gallery in Indonesia, and Museum Macan brought one of the bigger collections to the public without demonstration.

It's refreshing that we can discover artists with more controversial content in Southeast Asia. But it's worrying that many young collectors don't appreciate Indonesian art from the sixties or seventies. That's where institutions come in, and NGS is great for that. We have more academia also, publishing, and art history from the region.

I don't understand why my son returned from primary school one day, telling me he likes Kandinsky. Why is the local school teaching Kandinsky, not Georgette Chen or Cheong Soo Pieng? Why is Western instead of local art in the curriculum? If we don't study it, who's going to? Especially in Indonesia. Singapore can't do everything for the region.

HLI have mixed feelings, having seen the debates around documenta and REVOLUSI!. But I was encouraged by the last few days of documenta. The organisers could not have as many roundtable discussions as planned, but the intellectuals, artists, activists, and collectives continued the conversation.

We're already seeing artists from documenta extending the "lumbung" approach in their own ways. I'm excited to see how that will unfold. Perhaps it's an inspiration for new alliances to be formed between the collectives, private and public, as well as in public institutions within and beyond the region, for Southeast Asia, and even for both modern and contemporary fields.

RKI had some reservations when Ruru were appointed that this would be the framework Southeast Asian art would be viewed through for some time and that it would be difficult from a European perspective to talk about artists or collectives from Southeast Asia without referencing it. Things turned out much more complicated than I imagined.

For better or worse, this documenta's proposition, its organising principle, and its collective apportionment of resources are out there. People will learn from the experiment and find other ways to apply it. That's one thing to be optimistic about.

As Nathaniel was saying, the other thing that I've been optimistic about is how formerly marginalised topics and individuals have started finding avenues to come to public attention and be placed in dialogue with other modes.

More senior artists, women artists, and artists who might have been relegated to the category of craft. It doesn't just increase the number of forms that are accepted as contemporary art; it broadens the range of people who can speak.

That representation comes not from some altruistic sense of goodwill. The work is speaking with its own urgency. These communities are clamouring to be heard, and they're finding ways. That is something else to be optimistic about. —[O]