Trinh T. Minh-ha: Making The Fourth Dimension

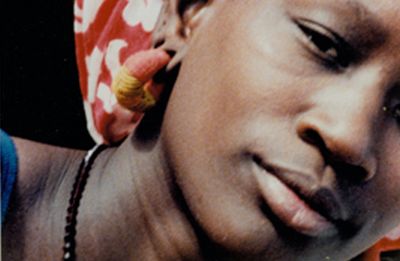

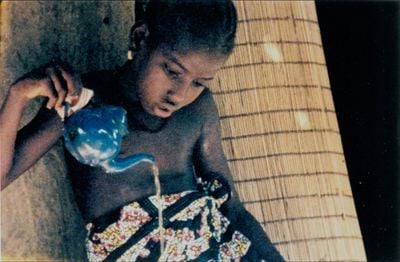

Trinh T. Minh-ha. Courtesy the artist.

Trinh T. Minh-ha. Courtesy the artist.

Vietnamese-born Trinh T. Minh-ha is a writer, theorist, composer and filmmaker whose practice, spanning some 30 years, is positioned within the fields of feminist and postcolonial studies.

A professor of Rhetoric and of Gender and Women's Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, Trinh studied music composition, French literature, and ethnomusicology at the University of Illinois after leaving Vietnam during the country's war in 1970 at the age of 17. As an exchange student, she attended the Sorbonne Paris-IV, and after finishing her PhD, she went on to teach in Dakar, Senegal for three years.

Senegal was the focus of Trinh's first 16mm film Reassemblage (1982), which documents the lives of women in rural Senegal. Reassemblage exemplifies the way the filmmaker approaches the subjects portrayed in her films—a position she has described as 'speaking nearby' rather than 'speaking about'. Trinh posits her works as 'boundary events', existing in a zone between labels—a place where new labels might form or dissolve or cross over one another, and which allows her works to evade categorisation. This is enhanced by reflexive cinematic techniques and editorial processes that challenge the traditional documentary form and deconstruct modes of thinking and looking at different cultures.

Since Reassemblage, Trinh has orchestrated a number of cinematic encounters with cultures from all around the world—including China, Vietnam, and Japan—and has more recently shifted to digital formats. The Fourth Dimension (2002), her first digital film, examines the culture of Japan through its art, culture, and social rituals and once more provides a multi-layered dimension in which to consider the effect of video on image making, as well as the use and passage of time in the moving image, and the act of 'seeing'. This conversation between Trinh and filmmaker Xiaolu Guo is an edited transcript of a talk held on 6 December 2017 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London as part of a retrospective programme of Trinh's work. The discussion zeroes in on the making of The Fourth Dimension.

These conversations are being published in the lead-up to Art Basel in Hong Kong this March, when ICA with M+ and Hong Kong Arts Centre will present Films by Trinh T. Minh-Ha at the Hong Kong Arts Centre, building on the recent retrospective at the ICA in London. This programme is organised in collaboration with the Department of Cultural and Religious Studies, Faculty of Arts, Chinese University of Hong Kong, and in association with Art Basel Hong Kong. The Hong Kong screenings will be followed by two discussions. On 28 March, a screening of The Fourth Dimension will be followed by a conversation between Trinh and artist Wolfgang Tillmans, chaired by artist Linda Chiu-han Lai. On 29 March, Trinh will be speaking with Professor Jia Tan and researcher Chương-Đài Võ after screenings of Forgetting Vietnam and Reassemblage.

XGThough it's your first digital film, I find such persistent, shared qualities between The Fourth Dimension (2002) and the first film you shot in Senegal, Reassemblage (1982), particularly in your aim to speak 'nearby' and not 'about' the culture that you are portraying. What has changed, or what has not, in your film practice since Reassemblage?

TMThe question of change or sameness is a little bit—to use terms of cinema—like stillness and movement. If we think of them as opposites, then we think, for example, of stillness as something that is rather stale, that does not change or move; and we think of movement as something that brings about change, that constantly renews itself.

For me, they are like two facets of the same coin. In stillness you can have full speed just like what video and digital technologies offer us, and in movement sometimes we appear as busy bodies, but actually we are stamping ground, staying in the same place. So it's not a question for me of changing or having something different. Change is always there.

Each of the films that I have made involves different encounters. For example, in Naked Spaces (1985), I journeyed across six countries of West Africa. In Shoot for the Contents (1992), I was venturing in China. And of course in Surname Viet Given Name Nam (1989), I was looking at something we could maybe call my own culture.

The more you look inside it the wider it gets—so what you think of as Vietnamese is not so Vietnamese after all, because the boundaries are constantly morphing. And with this we come to a film like The Fourth Dimension, and the encounter with Japanese culture.

In this encounter, am I an insider or am I an outsider? Asian cultures have a lot of inter-crossroads and similarities, but in terms of living in Japan—no matter how much you try to blend in, the outsider is an outsider.

XGI also want to ask you about your relation with your camera. In those films—including your fiction film A Tale Of Love (1995)—there is this uncertainty in the way the camera is operated that I find very interesting. You might pan the camera towards the left and we expect to find something extraordinary there, and yet there's a hesitation and you pan back.

In The Fourth Dimension I think your camera is much more certain than in your earlier films. But still you're not hiding the processes of zooming, panning, moving and trying to find your subject through one keen eye—so your process of filmmaking is completely visible for your audience and in a way the audience might feel as if they are operating the camera themselves. Can you talk about this?

TMYes, thank you so much, it's wonderful you have this feeling that you are operating the camera when you look at the film. The panning never goes from one specific point to another, which is what cinematographers usually rehearse at length so that they can give you a gesture that is impeccably confident.

In my case, it's the panning itself that is most important, so if you hesitate, it's your body movement that is manifested through the camera. In that sense it's not about going from one endpoint to another endpoint; it's everything that happens in between that's important.

When you pan, it's not as if what's in front of you is interesting—but the mere fact that you frame and you pan givesit full charge and intensity, so we look at it because the camera is capturing it.

The camera used in Africa was a 16mm that is often on a tripod or sometimes handheld, but in The Fourth Dimension I was using a palm-sized handheld camera and you can tell the movement is very different.

XGI'm of the generation that never shot film through a film camera. Shooting digital all my life has been both a blessing and a curse in a way; but you are of a generation that has had the privilege to use film cameras until suddenly you could use digital. How do you feel about this in terms of visual quality and your own relation to the camera?

TMIn terms of relation to the camera or to film in general, when you work with film there's no immediate quantification. You actually go through many phases and steps, whereas in video it's very intense because it's almost as if all of those phases are collapsed into one moment. So that's why, when I turned to digital technology, I had to deal with time.

To bring back Deleuze's three types of cinematic images—perception, affection, action—in the movement-image, and the difference he made between a cinema based on movement (movement-image), and a cinema based on time (time-image), I would say that all of my films are time-films.

The intensity of time and how we experience it is precisely what digital technology gave us. That's why I talk about speed in stillness. It's that kind of time.

XGIt really reminds me of Godard's Goodbye to Language (2014), and the intensity of the digital in his language that we're not used to; and also the vast transition between images and the video quality that he reinforced. I think that's what we feel in The Fourth Dimension, too. You made three digital films but all of your other films are on film, no?

TMYes. All the films before this one are 16mm or 35mm films.

XGAnother thing I'm very curious about is your intellectual heritage, or journey. You left Vietnam when you were 17, during the Vietnam War, and went to Illinois in the US where you studied music and literature.

TMWhile writing your PhD dissertation, you also left to study ethnomusicology in Paris, and then later on began your film career in West Africa recording tribal music and dancing in the 1980s.

XGThis is extremely unusual, especially when comparing your practice with that of Chris Marker or Jean Rouch, who came to China to record 'the other' or 'the otherness' away from Eurocentric culture. For me, it's a mystery how you operate with your own Vietnamese cultural heritage alongside the Western influence on your eyes and educated mind. Can you talk about this?

TMWhen Reassemblage first came out, the Asian-American communities were really not happy with it. They were very critical, and I often got the question: 'Why don't you make a film about our people, rather than go to Africa?'

Even today, I think many Asian viewers still have that question, and I think it's fine but in a sense I didn't calculate it. It just happened that when I was studying in the US, I was mainly sitting with international and African-American students, which led me to a very different path.

Also, the desire was not to stay in the US to find a job or go to France. I wanted to go somewhere else, and this was when Africa was suggested to me by my friends. But after I made two films in Africa, and I turned around and made Surname Viet Given Name Nam, it seems like the Asian-American community was a little bit happier with that situation. But for a very long time it was difficult.

XGAlso I guess there was a moment when feminist theory was coming to you, or you moved towards it. I remember I was studying at the Beijing Film Academy when I first saw Surname Viet Given Name Nam, but they didn't have Reassemblage, which might have been because of the nudity that it contains—there's still censorship in the Beijing Film Academy.

TMWhen I came to the UK and studied at the National Film School and saw your African films, it was a huge revelation for me in terms of what you were thinking and how you became who you are as an artist.

XGI really appreciate those famous words of yours concerning your intention to 'speak nearby' and not 'speak about' culture. I think that's an extremely different view from the male-centric judgment of culture—you have this position that is very clear, beautiful, and fresh.

TMI want to quote you here, from your book Cinema Interval (1999), where you say that 'most documentaries on Third World countries exist to propagate a first world, subjective truth'.

You also mention your American-centric anthropologist world and the so-called 'experts' of other cultures, saying that, 'They are so busy defending the discipline, the institution, and the specialised knowledge it produces that what they have to say on works like mine only tells us about themselves'.

XGCan you tell us about the difficulties that you've experienced as a writer and filmmaker in that world, over the years?

TMWell I think that if I've come to the point of saying things like that, it's also thanks to the hostility that my work received at the beginning. The first screening of Reassemblage at the 1983 Flaherty Film Seminar actually provoked such hostility in the audience, but fortunately for me, every time there is strong hostility, there is also strong defense.

So the audience was divided in two. At the time I had just come back from Senegal, and even though I knew the film was critical of the way anthropological films were made, I did not expect the audience to be right in front of me at the seminar. It was a very intense situation, and because of the continuous blows from one kind of audience to another, I have had to talk about the film lucidly.

This is not my way, because the films I make invite accidents, incidents; things that you have never thought of before, that resonate among themselves. It's about how you let the material come to you, how you do not simply impose a kind of subjectivity on the image, how you work with emptiness, how you work with the voice—all of this.

Because of the compartmentalisation of knowledge and the claim to expertise that keeps bringing up these divisions, one has to speak about one's work in a very lucid way. These are some of the difficulties. The way one speaks about one's work—even when you talk about your own work you don't indicate to people, 'This is what it is all about.' But you speak close to it, so it's the same kind of challenge as when you make the film.

XGRegarding your editing process, sometimes you create sound holes by cutting the sound off completely so that there is total silence, and then you might return to a completely different soundtrack.

The audience might be able to bear that kind of editing in a fiction film, but they sometimes cannot bear it in a documentary film, because it's supposed to be recording reality. I think this is a challenge to the traditional audience, and it really suggests the different ways of making film and the ideas that surround documentaries.

TMI don't do that to bother the audience. For me, it's about your relation to silence. There are many kinds of silences. Silence was very much a part of my every day in Vietnam, where something would be passed from one person to another in silence.

But every time I was silent in the States, people would be really bothered and unsettled and think that something was wrong or that they had said something unpleasant. But no, I was just really comfortable being silent next to another person. So this is how silence in a film can be amplified and in a way interrupt the viewing experience, and can become aggressive; but actually that very much depends on the viewer.

Viewers should assume their own representative space, in the sense that what they react to or what they see might say something about themselves. It's not always out there, with the film; it's a space that we share. So certain things came up because I decided on them, but other things appear with viewers in the way they consume images. And, depending on one's relation to silence, one may love it or one may hate it.

XGI want to come back to The Fourth Dimension, and the representation of rituals in Japan. In a past interview with film scholar Akira Mizuta Lippit, you said:

TM'What is spiritual is often identified, at least in the modern world, with mystification and institutionalised religion. A return to the traditions of old is also to be rejected as long as these are viewed only through activities of retrieval and of imitation rather than of creation in the present. This, I think, is the very problem we face today, both in the modern East and in the West, with our inability to see the spiritual in any other way than smugly and narrow-mindedly.'

XGCan you tell us more about what you think about the representation of the spiritual world in Japan, and its relation to your camera?

TMI would start with music. Music is not only in the notes that one hears or in the notes that are being played on an instrument—music is in the ear of the listener. The whole world is music, but we don't hear it. It's a little like the unseen or fourth dimension—we don't really hear it, but when we are in a certain state of mind and body, suddenly we hear it so intensely; every single little thing vibrates and it becomes so intense.

So I would say, similarly, spirituality is not just in the temple. Those who meditate know how much one has to sit with one's self in order to open up to the realm of silence—the kind of silence that is not opposed to sound, and how in that encounter one actually opens wide to the world.

This is a dimension of spirituality that I brought back when I said, maybe in order to see that spirituality we have to show the ordinary. Spirituality is not just confined to one thing, place, or person.

XGI also wanted to talk about your work as a theorist and a writer, and as a woman artist in this world. And as you mentioned, there is a difference between the written woman and the woman who is writing. This immediately made me think of Marguerite Duras, who writes about women and made a film about women, but she is also a historic female artist. Can you tell us about these two sides, and how you function between being a writer and a filmmaker?

TMThere are certainly a lot of similarities, but not in the same terms. I have spoken about how one goes into darkness to make film, and how one can demonstrate that knowledge is not what is most important in conveying a situation or even in giving information.

A film can be based on a situation of non-knowing. You can come in without luggage and be very fresh and invite people to watch a film that conveys everything that you see and hear as if for the first time. With writing, I never know what comes in the next sentence.

It's not like I have a plan that I sit down and follow, and yet unfortunately even now, when I publish books, I still encounter publishers who ask me to summarise them. It's mind-boggling, because if you already know everything that you are doing, you are merely illustrating thoughts you have already advanced. And when you explore, the question of language is at stake.

You don't explore with a language that is entirely familiar and expected. So even if you use exactly the same words as others use, the combination of these words solicit a different relationship.

When I do book readings, I've had women come up to me saying, 'You don't write like us.' And I ask, 'How so?' And they say, 'We just don't speak that way', and I'd say 'Oh, fortunately we don't speak the same way!' So if we don't speak the same way and we convey a different kind of relationship, obviously the question of language would have to be modified because language is not a mere instrument for thought or feeling; language is in itself a reality.

When one tends to take language for granted, what one can come up with is a situation in which one's subject is very progressive, but the writing is very regressive. So in a way it works against what you are trying to bring out. —[O]

—

A second conversation with Irit Rogoff, Professor of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, which took place on 7 December 2017, can be read here.