At Manifesta 14, Stars Reach Down to Earth

Petrit Halilaj, When the sun goes away we paint the sky (2022). Exhibition view: It matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise, Manifesta 14, Prishtina (22 July–30 October 2022). © Petrit Halilaj. Photo: Arton Krasniqi.

Manifesta, the European Nomadic Biennial of Contemporary Art, is characterised by its choice of locale. Every two years, the exhibition locates itself in a new city to facilitate discussions around the broader context of Europe and its borderlines, and test what art can do when it engages with a context directly.

This year, the 14th edition of Manifesta is taking place in Prishtina, Kosovo, the smallest and youngest state of the Western Balkans, whose difficult past defines a fragile present and uncertain future. After the end of the Kosovo War in 1999, the province was temporarily governed by a special UN body and was only declared independent from Serbia in 2008.

Kosovo's declaration of independence was greeted with different reactions around the world, dividing countries based on who recognised Kosovo and who didn't. Since, Kosovo has been striving to become a multi-ethnic functioning democracy, while struggling with poverty, corruption, and the growing privatisation of public spaces.

It is this privatisation that Manifesta 14 responds to most prominently, in a show titled It matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise (22 July–30 October 2022), curated by Catherine Nichols.

Proving that art does not necessarily need a museum and can meaningfully co-exist with the city, its problems, and its people, the event spans over 25 venues, sensitively revealing each location's past, identity, and sometimes second nature.

At one of the main squares, a yellow house installed by Alban Muja occupies the roof of the former Gërmia department store, recently saved from demolition thanks to civic resistance.

Muja's parasitic architecture, Above Everyone (2022), speaks to the urban reality of Kosovo, where the public housing system collapsed after the war, forcing citizens who lost their homes to build vernacular housing structures on top of other buildings without legal permission.

Such architectural additions are common in the urban reality of the former Yugoslavia and across the former Soviet Union, making Above Everyone a statement for civic creativity, stressing the urgency for an open debate about the future of public buildings and housing.

Manifesta 14's visual identity, designed by Bardhi Haliti, smartly stands out in the cityscape through the use of intense green round dots on the pavement that mark routes to different locations.

Not far from Gërmia, another colour catches the eye—this time, the pink foil Ugo Rondinone has wrapped around the contested Monument to Heroes of the National Liberation Movement. Built in 1961, during Tito's Republic of Yugoslavia, the monument's abstract form intended to symbolise a forward-looking socialist society free of ethnic tensions.

The former Brotherhood & Unity square where the statue is located was renamed after Adem Jashari, a figure of the Kosovo Liberation Army, around 2000, and there have been persistent attempts to replace it with another dedicated to Jashari.

Rondinone's daring gesture of wrapping the monument in vivid pink material stirs the debate around commemoration in a changing society. Although the choice of colour is unexplained, it implies a demilitarisation and feminisation of its male and martial allusions.

A more subtle intervention in Prishtina's skyline that also evokes a de-militaristic stance is Flaka Haliti's Under the Sun – Explain What Happened (2022), which is installed on top of the emblematic brutalist building of the Palace of Youth and Sports.

In the afternoon, the panels glow and burn with the sun, forming an uncanny horizon haunted by the spectre of the past.

To make the work, Haliti appropriated ten plastic panels from a former KFOR military hangar, a NATO-led international peacekeeping force near the city of Prizren. After 20 years of sun exposure, the light-coloured panels have turned dark reddish-brown.

Haliti framed these panels with a scaffolding of metal silhouettes in the form of clouds that evoke military camouflage. In the afternoon, the panels glow and burn with the sun, forming an uncanny horizon—a reminder that the present is haunted by the spectre of the past.

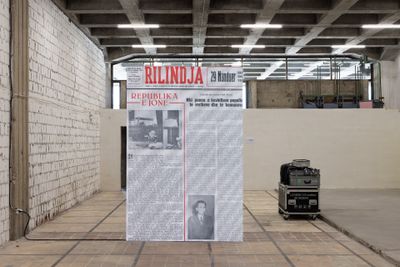

The memory of space is brilliantly approached in the site-sensitive environment by Cevdet Erek at Rilindja Press Palace, another icon of brutalist architecture that once hosted the Balkans' most-read newspapers. Like many buildings in Prishtina, it was privatised after the war, and served as a nightclub, among other things.

In Brutal Times (2022), the artist engaged with the abandoned section of the building, where he installed a large L.E.D. screen with rhythmically changing pages of the Rilindja newspaper, and a sound-and-light composition suggesting an underground techno party.

If every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end—and not necessarily in this order—Manifesta 14 focuses on the moments between.

At the Grand Hotel Prishtina, Manifesta 14's central venue, bright golden stars appear to be falling onto the tall building's façade. The poetic title of this light installation by Petrit Halilaj, When the sun goes away we paint the sky (2022), appears as signage in Albanian on top of the building.

Before the war, the Grand Hotel had been a prestigious five-star hotel, hosting important political and cultural events, as well as one of Kosovo's main contemporary art collections. Today, its semi-abandoned state makes for a ghostly and nostalgic atmosphere.

In reflection of this derelict monument, Halilaj invites Prishtina's citizens to wish on the falling stars materialised by the work, daring them to imagine a better future. The gesture connects with Manifesta 14's engagement with long-term infrastructural projects led by design-and-innovation firm Carlo Ratti Associati, which utilise the methodology of open-source urbanism, based on civil participation and feedback to create lasting change in the urban and social fabric.

Working with public space is not easy: things can change unexpectedly and it's impossible to control fully, even as shared spaces fall prey to privatisation and commercialisation. If one decides to work in public, one has to acknowledge the reality that public life and its spaces might be more radical than art can ever be.

With that in mind, Manifesta 14's central exhibition, The Grand Scheme of Things, unfolds across eight floors of the Grand Hotel with a curatorial strongly inspired by multispecies feminist Donna Haraway's ideas of making more-than-human worlds.

Each floor revolves around one particular notion—transition, migration, water, capital, love, ecology, and speculation. While such a structure insists on distinctions, themes entangle with one another through artworks.

Some of the strongest positions within the show come from Kosovo and its diaspora. The joyful, surreal paintings by Kosovo's most prominent modernist Nusret Salihamixhiqi (1931–2011) fuse together plant, animal, and machine spirits.

Equally surreal, yet much darker, are large-scale canvases from 2020 and 2022 by Brilant Milazimi, which depict figures with unnaturally long limbs and teeth, evoking traumatic yet fascinating dissociations.

Made between 2013 and 2022, Artan Hajrullahu's small-scale drawings feature familial, domestic scenes, giving special attention to quotidian acts of eating watermelon, sleeping on a couch, taking a bus, or kissing.

'Your enthusiasm to tell a story' (2015–2022), Dardan Zhegrova's installation featuring life-size voodoo dolls with oversized eyes and big hearts, invites viewers to lay down and listen to each doll's voice.

These inanimate objects reflect the fluid boundaries between self and other and conjure moments of empathy and strange intimacy, appealing to the pleasure the supernatural world can provide.

Poetry permeates the work of Driton Selmani. In his series, 'Love Letters' (2018–ongoing), plastic bags displayed on the walls behind plexiglass stress their archaeological character as artefacts. Each bag ignites poignant snapshots of the present that contrast the longevity of the material, which is believed to take as long as 1,000 years to degrade.

Freedom of travel cannot be taken for granted for Kosovo citizens, as visa procedures often create stretches of suspenseful waiting. there are crossroads where ghostly signals flash from the traffic (2022) by Edona Kryeziu, explores Kosovo's geopolitical position and its symbolic distance to the E.U. in a meditative setting—a two-person swing hangs from the ceiling surrounded by columns of boxes and parcels.

An acoustic landscape fills the room mixing field recordings from Sounds of Kosova (2001), an album recorded by students of the Center for New Music in Prishtina just after the war, with sounds gathered by Kryeziu herself during her travels to and from Prishtina.

Across interventions like these, Manifesta 14 finds balance in the delicate interplay between its geographical context and artworks, creating meaningful moments that embrace uncertainty in a place in transition.

With that in mind, it's important to note that some of Manifesta 14's projects, like the Centre for Narrative Practice, which is home to Manifesta's rich education programme, intend to continue beyond the 100-days of the exhibition.

If every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end—and not necessarily in this order—Manifesta 14 focuses on the moments between. Because some ends have to be untold before new beginnings can emerge.—[O]