Net Art's Archival Poetics at the New Museum

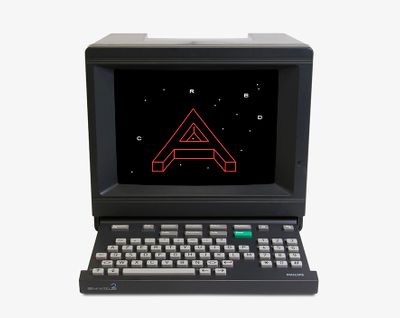

Eduardo Kac, Reabracadabra (1985) (reconstruction). Animated poem for Videotexto. Courtesy the artist.

How should net art be classified, historicised, and exhibited, when time has elapsed between its initial production and its latter presentation? On view at the New Museum from 22 January to 26 May 2019, The Art Happens Here: Net Art's Archival Poetics presents 16 seminal artworks from Net Art Anthology, an ambitious two-year initiative undertaken by Rhizome to research, preserve, and exhibit 100 artworks online, in an attempt to answer that question.

Curated by Rhizome's artistic director Michael Connor and assistant curator Aria Dean, the show is staged across the first-floor gallery of the museum, and situates artworks within the history of net art, a domain simultaneously tied to and excluded from mainstream discourses of contemporary art. The Art Happens Here is not centred around one specific period, but constructs an expansive and fluid timeframe instead, with dates of creation varying from the mid-1980s to the present day.

This approach to time is mirrored in the exhibition's exploration of media. Far from being limited to the browser or computer, the works on view run the spectrum of sculpture, installation, website, slideshow, video, merchandise, and other formats. Shu Lea Cheang's Garlic=RichAir (2002), for example, restages the original series of travelling performances—plus an interactive website—that featured on-site bartering, which the artist co-produced with CREATIVE TIME. In one gallery, an orange-paneled electronic cargo tricycle filled with heaps of garlic is installed, with one monitor showing how the plant is harvested, and another displaying scores from an online trading game. Deploying her characteristic cyberpunk sensibility, Cheang imagines a future where garlic functions as a post-capitalist currency that is traded online to forge communities, explore alternative economies, and further ecological awareness.

Just as Cheang's work hinges on the converging point of the virtual and the physical, the show's lack of medium specificity and chronological narrative seems to push back on the central platform where net art activities took—and take—place, apprehending the genre instead as a hybrid practice and thematising device. This approach is less interested in differentiating between what we now call net art, software art, new media art, and post-internet art, as it is in mapping out a more general field typified by its acute awareness of network culture at large.

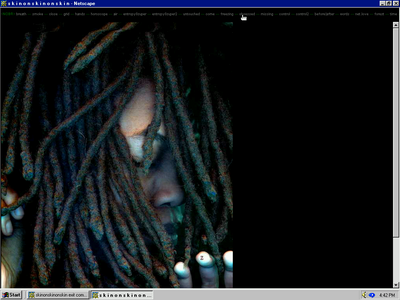

What does poetics of the archive refer to? One could perhaps begin by thinking about how artworks utilising certain technologies change, degrade, or dissipate over time. In fact, recognising the importance of preserving and archiving precarious works was what prompted the creation of Rhizome's Net Art Anthology in the first place. 'skinonskinonskin' (1999) began as a series of interactive webpages exchanged between artists Entropy8 and Zuper!, for whom poems, quirky hyperlinks, and animated gifs written using JavaScript, HTML, and Flash, were expressions of love, consent, and mutual exploration. Now, due to technological obsolescence, the website instead is accessed through a Windows 98 emulator, which is how it is displayed in the show. Furthermore, what used to be a private, intimate correspondence between the two has become a publicly available artwork online, where the imagery of a sleeping woman can be animated with a simple mouseover from anyone, thus acquiring an undeniably voyeuristic dimension.

Olia Lialina's nostalgic piece Give Me Time / This Page is No More (2015) is a literal take on the act of archiving. Consisting of a set of slide projections, Lialina selected websites that were either under construction or abandoned on GeoCities, a web hosting service that is now defunct. The slides were selected from a broader archival project orchestrated by the informal Archive Team, for whom Lialina and her partner, Dragan Espenschied undertook restoration. These fragments of 'digital folklore' dive back into a time when the web was not yet monopolised by sleek, minimalist, market-driven content. Before the widespread popularity of social media platforms, these websites were important outlets for personal expression, with distinctive amateurish, DIY styles including neon colours, gifs of dancing skeletons, and kitsch comic sans fonts. Salvaged from eternal obscurity, anonymous pages that read 'I will be back soon...I mean it' seem to be permanently suspended in time, as if the user could be back any minute.

As net art's core concerns shift over time, and techno-utopian ideals regarding the radicality of the open net prove to be a lost cause, it is evident that generalised emphasis on decentralisation, anti-institutionalisation, and individualism that defined the 1990s and onwards have become more dispersed, directed, and culturally inflected.

Morehshin Allahyari's series 'Material Speculation: ISIS' (2015–16) presents intricate and miniaturised 3D printed sculptures: products of painstaking research conducted to replicate a number of traditional artefacts destroyed by ISIS. The semi-transparent resin reveals SD cards embedded within the sculptural body—they cannot be accessed without breaking the models open. In mainstream media, 3D printing is often portrayed as a revolutionary and democratising enterprise, as its supporting software is generally shared across open-source platforms. The data in Allahyari's project is intended to be released at a future time through an institution in the Middle East, and considers how digital technology could give new life to destroyed heritage. The decision to withhold most of the research from online circulation emerged from the realisation that this very technology is mostly inaccessible to people in that region, largely due to a skewed digital infrastructure or information vacuum.

While Allahyari's multifaceted work underscores the ambiguities of an emergent material practice by thoroughly utilising it, Bogosi Sekhukhuni's dual-channel video installation Consciousness Engine 2: absentblackfatherbot (2015) delves into an affective rumination on the potentiality and limitations of technological intimacy, without engaging with the actualities of machine intelligence. He stages two avatars in order to simulate a dialogue that took place in an online chat between the artist and his father: two eerie floating heads converse with one another in artificial text-to-speech robot voices, shifting from mundane topics like favourite types of music, to philosophical questions concerning human consciousness.

Whereas some are intrigued by manifestations of networked technologies in the cultural sphere, artist duo YoHa (Graham Harwood and Matsuko Yokokoji) hark back to the calculating machine and its software counterpart as a means to explore sinister connections between forced labour, corporations, and information processing. In their installation Lungs (2005), a computer is set up to display an array of vital inputs on 4,500 slave workers forced to work at an ex-munition factory in Karlsruhe, Germany, such as age, gender, height, and weight; while an application calculates the workers' lung capacity and simulates a sound equivalent to the last breath of air they emitted. As the chilling, rhythmic vibrations echo across the space, sets of data are animated and made human, just as software prototypes have rendered countless bodies inhuman.

If the deliberate refrain from historical and discursive framing in The Art Happens Here has succeeded in creating a more inclusive and laidback curatorial platform through which to consider net art and its legacies, it has also weakened aspects of its execution by omitting crucial points of political and cultural contextualisation. Miao Ying's 2007 work Blind Spot, for example, consists of an open Chinese dictionary with certain words covered with white tape lit from above. Taking on a repetitive, labour-intensive exercise over a period of three months that embodies the censorship prevalent with the Chinese internet, Miao manually blocked out every word that she discovered has been black-listed on google.cn. Without further explication and documentation, the work risks painting a black-and-white, Black Mirror-esque picture whereby state dominance strips users of any agency. Not shown or mentioned is the myriad of ways that Chinese users have developed tactics—including wordplay—to circumvent censorship and contribute towards various activist movements.

As the title of this exhibition suggests, net art is happening in the here and now and is subject to rapid dynamic change; so much so that works in this genre are replete with their own mythologies that take much time and effort to research and decode. Each time a work is exhibited, it automatically becomes an act of re-enactment, re-performance, and re-iteration. As of 2019, Google.cn has ceased to exist, and artificial intelligence has been widely integrated into corporate data collection and mass surveillance. By embracing the nebulousness and vitality of network culture as a whole, The Art Happens Here offers a diverse showcase of critical projects, while highlighting inherent paradoxes within such showcases of net art at large. —[O]