Who Is Melly Shum? On FKA Witte de With’s Name Change

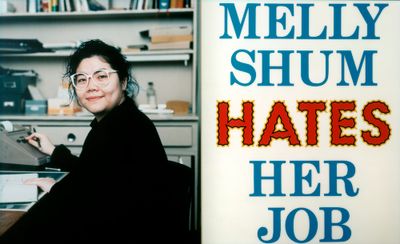

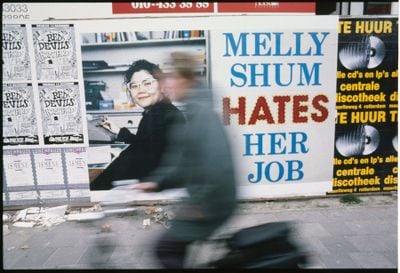

Ken Lum, Melly Shum Hates Her Job (1990) on the wall of FKA Witte de With, Rotterdam. Courtesy FKA Witte de With. Photo: Bob Goedewaagen.

On 2 October 2020, the institution formerly known as Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art (FKA Witte de With) announced its new name, Kunstinstituut Melly—the result of a three-year process initiated by an open letter sent in June 2017 by Egbert Alejandro Martina, Ramona Sno, Hodan Warsame, Patricia Schor, Amal Alhaag, and Maria Guggenbichler.

The letter questioned FKA Witte de With's ability to perform 'critical work' as an institution named after a cruel, high-ranking naval officer active in the Dutch colonial system, who took part in the siege and destruction of Jayakarta (current Jakarta), and punitive actions in the former East Indies. It was picked up in the national press and gained momentum.1

FKA Witte de With, located on the eponymous street, responded by opening itself up to discussion. The 'Name Change Initiative' was launched soon after Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy began her tenure as director in January 2018, and in May that year a policy of 'unnaming' exhibitions was instituted while a 'publicly-focused, and socially oriented' ground-floor space named 'UNTITLED' was opened.

In response to demands for transparency, FKA Witte de With disseminated reports concerning its process online on wdw.nl from 2018 onwards, and on change.wdw.nl since June 2020. Eventually, 'through a Public Input phase involving over 280 participants in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and Internationally',2 including 'an Online Survey and five Forums', a shortlist emerged with three potential names: KAT, kin, and Haven.3,4

But, according to the public reports, on 23 September 2020, 'an external Advisory Committee made up of 13 respected figures in the field of culture and emerging leaders in the arts . . . proposed Melly as an additional and better name' during a '"What's missing?" discussion-round' after KAT had been voted as the favourite.5,6

To better understand why 'Melly' prevailed over three publicly vetted options, we must inspect the origins of Melly Shum Hates Her Job (1990), Ken Lum's image of a young woman sitting in a cramped office, from which the name is derived.

When FKA Witte de With opened in 1990, Lum staged the inaugural solo exhibition, which included a commission for a billboard version of Melly Shum Hates Her Job installed at various locations in the city.7 The billboard on the outside wall of FKA Witte de With was removed after the show, but re-installed following popular demand.

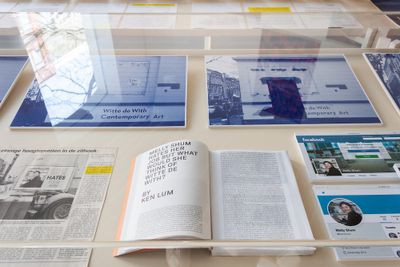

Fast forward to the onomastic crisis of the late 2010s. In April 2019, FKA Witte de With renamed its 'UNTITLED' ground-floor gallery space to 'MELLY'—a name, per the press release, coined by 'young Rotterdamers' who participated in a work-study programme at FKA Witte de With from September 2018 to February 20198. The press release explicitly references the ongoing Name Change Initiative, describing the renaming of UNTITLED as 'part of an identity proposal which, overall, emphasizes multiple viewpoints of collective experiences', while underscoring that 'MELLY does not replace the name Witte de With'.9

That month, the exhibition On Melly Shum, curated by Hernández Chong Cuy and Stijn Kemper, opened in MELLY, which clearly situated Melly Shum Hates Her Job as an original site of FKA Witte de With's identity. This could be read as a staging of a pre-set narrative. One report mentions 'the institution's naming case-study (from Untitled to Melly)', and points out that 'by now', Melly 'signifies not only a person but a process that the institution has undergone, both architecturally and socially from the "bottom up".'10

There is no evidence in the publicly available reports that the name was proposed during the public 'bottom-up' consultation rounds. These reports instead show that 'Melly' only first appears as a serious option during the meeting of the External Advisory Commission, when it was floated as 'what's missing', and was subsequently adopted. The change was officially ratified during a final public review,11 and the entire process was deemed 'co-constitutive'.12 Here was a new name referring to a woman of colour with an office job she hates—the ideal decolonial subject to adorn a prestigious art institution.

But what has been lost is the reason why FKA Witte de With's name was removed: because of who the person was and what he had done. So, the question remains: Who is Melly Shum?

I reached out to FKA Witte de With and Ken Lum to learn more. Initially, Lum evaded some of my questions, insisting on the 'model's privacy'. Upon further prodding, he confirmed that Shum was a former student and that this was her real name. 'I can't say whether she knows of the new name for the institute', Lum pointed out. 'She has made it clear her life is separate from the work' and 'prefers not to be updated' on it.13

Lum's narrative, which implies no explicit consent was asked on the basis of Shum's request for privacy, appeared at odds with the answers I received from Hernández Chong Cuy, which suggest that Shum was actively involved in the decision-making process both in 2018–2019 and recently14.

So, the question remains: Who is Melly Shum?

Yet, upon my repeated request to confirm Shum's personal and explicit consent, Hernández Chong Cuy responded with: 'we reached out to Melly!'15 without indicating whether an actual conversation or consent followed. In a later email asking further clarification, Hernández Chong Cuy stated that Shum was 'amused and supportive'.

There are two options here. Either my exchanges with Lum and Hernández Chong Cuy enhance a fictional narrative around a character named 'Melly Shum'—Shum has, after all, been referred to as fictional in numerous texts on the subject.

In that case, the two main parties involved in the name change would be the institution and the artist, with the institution expanding the myth around the work, enlarging the artist's cultural capital, and logically extending its investment into his work since 1990.

If either Lum or FKA Witte de With declare this to be true, the consent issue is off the table, but the question as to whether a fictional, imaginary subject of colour would be an appropriate donor of FKA Witte de With's new name as a 'decolonised' institution remains.

The second option is that Melly Shum is an actual, living person, whose name is now appropriated by an international art institution, without her consent. This is also a question of labour. It is understandable that Shum at some point refused to engage further with Melly Shum Hates Her Job and asked to be left alone. But does this warrant the appropriation of her name?

In an article discussing Melly Shum Hates Her Job, Lum commends FKA Witte de With for having 'absorbed [the] lessons from conceptualism'15. Perhaps the thorny issue of myth and consent could be circumvented by claiming that Melly Shum Hates Her Job extends to the institution, as if Lum's work first intruded through the ground-floor gallery before enveloping FKA Witte de With, miraculously turning the simulacrum on the outside wall into institutional signage.

Whatever the truth, it appears that FKA Witte de With 'absorbed' the 'lessons of conceptualism' so well, that it could not radically break with the colonial past that its original name (and quite a few tenets of conceptualism) implies. The same institutional gesture that takes on the name from a street sign on its outer wall in 1990, now appropriates the name of a work situated just around the street sign's corner.

Cannibalising its urban context, FKA Witte de With cannot not acknowledge its indebtedness to a tradition of conceptual art and is unable to resist its logic. This shows both the efficacy of Lum's work and the institution's ultimate failure to question precisely the mechanisms of appropriation, language, and abstraction that underlie it.

There are other points of friction. In his email, Lum states that Melly 'has made it clear her life is separate from the work'. But was FKA Witte de With not renamed precisely because of the life its former name signified? Is it not strange, then, that the institution has chosen the name of a work that is separate from the life of its subject, fictionalised or not?

In choosing a familiar 'conceptualist' continuity, FKA Witte de With has committed another act of symbolic violence: the truncation of Melly Shum's full name. With her clearly Asian surname, the signifier of otherness, removed, only a supposedly universal and ethnically non-specific, yet Anglophone, first name remains.

This omission is not innocent. It was first made possible through a switch from 'UNTITLED' to 'MELLY' (note how much compensatory work the all-caps are doing here) on FKA Witte de With's ground-floor gallery, to then be translated (and further downscaled) to the 'Melly' of the institution as a whole. From 'Melly Shum' to 'MELLY' to 'Melly'. One wonders how such gesture, in the words of Hernández Chong Cuy, 'responds to the claims raised by the larger decolonial movement'.

Has FKA Witte de With failed 'to come to terms with its own internal contradictions'? Did it fall prey to its desire to have a good name that represented its engagement with society, its internal complexities, while also honouring its situatedness in the vibrant heart of Rotterdam?

Perhaps that structural desire to belong—a belonging denied to so many and viewed with suspicion by others—is what made this enterprise step into precisely the pitfalls it conspicuously, but perhaps also superficially, sought to avoid.—[O]

1 See, for a detailed timeline, 'Timeline #1: Debates about the Institution's Name and Actions of its Name Change Initiative', [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/timeline1/]

2 FKA Witte de With, 'Report #8', change.wdw.nl, 23 September 2020, [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/report8/]

3 FKA Witte de With, 'Report #9', change.wdw.nl, 26 September 2020, [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/report9/]

4 FKA Witte de With, 'Report #12', change.wdw.nl, 2 October 2020, [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/report12/]

5 Ibid.

6 FKA Witte de With, 'Report #8', change.wdw.nl, 23 September 2020, [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/report8/]

7 Ken Lum solo exhibition, curated by Chris Dercon and Jon Tupper (8 December 1990–20 January 1991), [https://www.fkawdw.nl/en/our\\\\\\\_program/exhibitions/ken\\\\\\\_lum]. See also: Ken Lum, 'Melly Shum Hates Her Job But Not the Witte de With', in Everything Is Relevant: Writings on Art and Life (1991–2018) (Montreal: Concordia University Press, 2020), p.198–202. The original essay, published in Zoë Gray, Nicolaus Schafhausen, and Monika Szewczyk, eds., 20+ Years Witte de With (Rotterdam: Witte de With Publishers, 2011), p.36–43, was titled 'Melly Shum Hates Her Job But What Would She Think of Witte de With?' So it appears that in the nine years that passed, Melly Shum made up her mind.

8 FKA Witte de With, 'UNTITLED is renamed MELLY at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam', 7 April 2019, [https://www.wdw.nl/files/press\\\\\\\_release\\\\\\\_MELLY.pdf]

9 Ibid. The case study is also mentioned in 'Report #7', change.wdw.nl, 22 September 2020, [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/report7/]

10 FKA Witte de With, 'Report #10', change.wdw.nl,–27 September 2020, [http://change.wdw.nl/reports-media/report10/]

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ken Lum, email to the author, 5 October 2020, 15:04 CEST. Lum confirmed for De Volkskrant that 'his former student leads a withdrawn life in Canada.' Ashwant Nandram, 'Het kunstcentrum in Rotterdam, voorheen genaamd Witte de With, gaat Kin, Kat of Haven heten. Of Melly?', De Volkskrant, 27 September 2020, [https://www.volkskrant.nl/cultuur-media/het-kunstcentrum-in-rotterdam-voorheen-genaamd-witte-de-with-gaat-kin-kat-of-haven-heten-of-mellyb522f293/]

14 Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, email to the author, October 6, 2020, 08:44 CEST.

15 Ibid.

15 Ken Lum, 'Melly Shum Hates Her Job But Not the Witte de With', Everything Is Relevant: Writings on Art and Life (1991–2018) (Montreal: Concordia University Press, 2020), p.200. My emphasis.