Yinchuan Biennale: 'Starting from the Desert. Ecologies on the Edge'

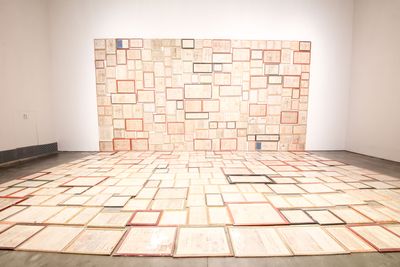

Kimsooja, Bottari (2018). Exhibition view: Starting from the Desert. Ecologies on the Edge, 2nd Yinchuan Biennale, MOCA Yinchuan (9 June–30 September 2018). Courtesy MOCA Yinchuan.

Hovering above sprinkler-coaxed beds of grass, the curved architecture of MOCA Yinchuan alludes to the topography of its more natural, flanking geographies: the desert and the marshland, divided by the Yellow River in China's northwestern Ningxia province.

Between sand and water, it is the desert that Marco Scotini, curator of the 2nd Yinchuan Biennale (9 June–30 September 2018), has chosen as the exhibition's starting point. Titled Starting from the Desert. Ecologies on the Edge, the exhibition considers how new ecologies might arise from nomadism, a 'wandering science', as Scotini describes it in his curatorial essay, that oppose the constant and stable structures of civilisation. 'The Edge' in Scotini's essay's title refers to the periphery of the desert, a point where diverse eco-systems may 'encounter one another and stratify'—as reinforced in the exhibition's focus on the western borders of China, with the work of 90 artists from over 30 countries and regions.

In recent years, Yinchuan has joined the ranks of China's 'smart city' pilot projects, where tech and infrastructure are entwined as a means of improving daily life; including solar powered waste bins that open as they are approached, and the more futuristic facial recognition on buses linked to bank cards. As a blueprint city, it comes as little surprise that MOCA Yinchuan is set an hour south of the city itself; the distance between the museum and the city proper speaks to its future growth. MOCA Yinchuan is the first contemporary art museum in northwest China, and is intended to move hand in hand with Yinchuan's infrastructure, implemented as a means of drawing in populations from rural areas.

As such, the Yinchuan Biennale is a stretch for anyone to reach, which pushes questions about how art might be created and exhibited in such zones. In his text for the exhibition's first thematic section, 'From the Nomadic Space to the Rural Space and Reverse: To Invent a Becoming Artist', art theoretician Lu Xinghua considers how the smooth field of the desert could be conducive to the will to experiment and create, forcing artists to become 'nomadic war machine[s]'.

The question of nomadism is addressed in a ground-floor gallery darkened by a portion of deep grey walls. A wooden, canvas-covered yurt sits beside nine metal pales filled with water, upon which are laid two wooden poles with what appear to be yak's hooves at each end. A sheepskin rug, bamboo mat and video depicting the yurt across Mongolian landscapes, are tucked into Enkhbold Togmidshiirev's installation My Ger (2017–2018), which constitutes part of the artist's decade-long focus on the structure and tradition of the Mongolian yurt. Over his career, Togmidshiirev has transported portable yurts across different urban settings around the world—initiating a contrast between their organic form and hard urban structures to highlight the way in which traditional, rural nomadism has become a foreign manner of existence in the contemporary world.

Placed behind Togmidshiirev's installation in an immense photograph by Kyrgystani artist Aliman Jorobaev, Oral Creativity (1990–2016). A man casts his hands away from his body, as if telling a tale left to the imagination of the viewer. The work is taken from an extensive series titled 'The Great Silk Road', in which Jorobaev explores the fragments of nomadic existence that remain between Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, despite the massive changes that have occurred in Central Asia in recent years.

Besides considering the desert as a 'smooth space of dynamic flows', Scotini also considers the extreme landscape as a means of emphasising human impact on the earth. Moving further inwards to the first gallery, a collection of comparatively bright, airy works in paler tones offer more distinct references to the landscape. These include an installation by Kiluanji Kia Henda, comprised of pieces including Rusty Mirage (The City Skyline) (2013), a series of photographs of sculptures created in the Al Zaraq desert in Jordan that hint towards the empty infrastructures that burst from inhospitable lands for the rush of capital. Another series of photographs shown by the artist is Instructions to Create Your Own Personal Dubai at Home (2013), which presents beer cans, matches, or circuit boards arranged in architectural structures as how-to guides to create DIY versions of landmark Dubai skylines in one's home.

The estrangement between humans and nature is emphasised in Zhuang Hui's installation Zhuang Hui Solo Exhibition, which was originally presented in 2014 at Platform China Contemporary Art Institute in Beijing as a one-week exhibition. Zhuang Hui, who comes from Yumen—a desert town on the northwestern edge of China—set off on a series of trips to the Gobi Desert, where he placed existing artworks and painted murals on ruined buildings, adding bursts of form and colour in an otherwise desolate landscape. He captured these interventions in a series of photographs that are exhibited along two walls at the far end of the gallery in this exhibition, sectioned off by a free-standing wall, at the back of which a large flag is propped up, depicting four men walking across a barren landscape while carrying a bright red block on their shoulders. As with Henda's work, the distance between humans and earthly matter is complicated in order to disrupt the relationship between the two.

Walking out of the first gallery and across the museum's atrium, a second gallery continues the section 'Nomadic Space and Rural Space' with a play with landscape, where viewers can climb on to a podium to observe a series of textiles laid out on substructures of many sizes, ranging from carpet works such as Hiwa K's For a Few Socks of Marbles (2012), to Alighiero Boetti's Senza titolo (1994), along with two polyurethane 'maquettes' from Piero Gilardi's 'Nature-Carpets' series, conceived as fragments of the landscape presented as hyper realistic slices of stony river beds.

Descending floor-level towards the back part of the hall, a wall sections off another series of installations, including Kimsooja's glossy, silken cloths in bright colours hung from wire, as if being left to dry. Titled Bottari (2018), the installation refers to the Korean cloth bundle of the same name that is used to carry objects such food or gifts. The fabrics used in the installation are Korean bedcovers made of fabric from the Ningxia region, which, for the artist, represents the cycle of life. ('[I]t is upon them that people are born, dream, love, rest and ultimately die,' suggests the artwork's description in the catalogue.)

Concealed behind the partitions containing this installation, Yinchuan-born artist Mao Tongqiang's project Leasehold (2009–2018)—a selection of his 1,300 land ownership papers of different periods—are packed together in frames of varying sizes on the wall and out, towards the viewer on the floor. Now obsolete, these once-treasured papers hint towards a time before the collectivisation of land ownership in China that occurred in the 1950s.

The focus on the third floor is organised around the themes of 'Labor in Nature and Nature in Labor', and 'The Voice and the Book and Minorities and Multiplicities', with each section containing a dense selection of multi-layered installation works. 'Labor in Nature and Nature in Labor' is consolidated in the first gallery here, which explores the vision of nature as separate from humankind, most powerfully in Pedro Neves Marques' film YWY, The Android (2017). A woman with long, deep brown hair, wearing a brown leather jacket stands surrounded by the green stalks of corn plants. She speaks, (as if to the plants themselves) about bodily rights, infertility, labour, and monocrop plantations.

Curving through the room, the archival-heavy installation Sowing Somankidi Coura, A Generative Archive (2015–ongoing), a long-term research project by Raphaël Grisey and Bouba Touré, explores the self-organised cooperative of ex-migrant workers and activists in France in 1977, Somankidi Coura, who founded the agricultural cooperative along Senegal river in 1973, after the Sahel drought. Using archives such as books, films, photographs, and letters, the installation weaves Pan-African history with the liberation struggles of workers in France with a communion over permaculture to construct a narrative of empowerment in a place of mass rural exodus towards cities or Europe.

Reflections on territorial abandonment appear again in the neighbouring room, where Francesco Jodice's Aral Citytellers (2010) highlights a series of drastic transformations in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan after the fall of the Soviet Union. These include the shrinking of the Aral Sea due to water diversions for irrigation; the dismantling of the top-secret Vozrozhdeniya island laboratories, an experimental centre for chemical weapons and now one of the most contaminated areas in the world; and the territorial changes that occurred around the Baikonur Cosmodrome, which was built in the Mongolian steppe by the Soviets in 1952 before coming under Kazakh territory after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The shifts of power that these three narratives represent is illustrated in three informative paragraphs on a single-standing wall, which sections off a corner of the room, with an image of a rusty, abandoned boat set against a pale blue sky taking up the wall's opposite side—hinting towards the once-thriving fishing trade of the Aral Sea. On the walls, translations in Chinese are accompanied by a further series of dusty, pale-toned images capturing the landscapes in question.

Winding over to the next gallery, another series of installations populate the section 'Minorities and Multiplicities', which includes Moataz Nasr's work Blue and White (2012): 30 ceramic vases that resemble blue-and-white Chinese porcelain with, on closer inspection, fragments of religious and political propaganda incorporated into their patterns, from 'Allah' and 'Al Jazeera' to 'Down with Military Rule'—loaded phrases referencing upheaval in the contemporary history of his homeland, Egypt. The blue-and-white pattern of traditional Chinese ceramics is one of the most emblematic objects of the Silk Road's material history, with many overlaps occurring between ceramics made in the Islamic world, China, and further afield. (The once-scarce cobalt pigment used to pattern Chinese wares was originally imported from Persia during the Tang dynasty, 618–907.1)

Language appears again in Mariam Ghani's The Garden of Forked Tongues (2016). Focusing on the northwest region, Ghani recreates a map of China in coloured chalk on a blackboard, in which sections are coloured to designate the country's linguistic diversity in 1987. As the chalk gradually fades from the wall while the exhibition continues, the work becomes a homogenous blur—representative of the erosion of linguistic diversity in China since 1987. With Xinjiang close by, where ethnic Uyghur and Hui minorities are currently experiencing a political crackdown in the name of social stability and a fight against radicalism, the work cautiously hints towards the impact of such control, focusing in this case on language.

The need for social stability in Xinjiang is related to its geographical position: home to some of the largest reserves of natural resources in China, in a region that sits on one of the most important pipeline routes into Central Asia (where its deposits of natural gas, oil, and nonferrous metals are exported). With China being the largest coal producer in the world, Navjot Altaf's three-channel video work Soul, Breath, Wind (2018), shown in its own room in the section 'Labor in Nature and Nature in Labor', highlights the displacement caused by mining to the local population and the impact on the ecology in the state of Chhattisgarh in India. In this pertinent exploration of the consequence of mining, the question of sovereignty over land and who has the right to it is raised throughout.

Returning to the museum's first-floor atrium, Beijing-based artist Song Dong's Biennale-commissioned work The Center of the World (2018) acts like a drawstring to the entire exhibition. A series of wooden steps diminish in size as they move upward, like a pyramid, until reaching a small, flat top, upon a sign reads in both English and Chinese: 'The Center of the World'. It is a refreshing relief to the sense of overwhelm that is inevitable when viewing an exhibition of such scale—a reminder that there is not one standpoint to encounter here, but many. —[O]