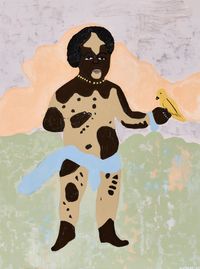

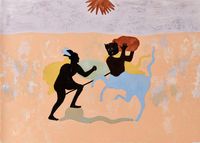

Goodman Gallery is pleased to present To live long is to see much, Cassi Namoda's first exhibition with the gallery.

This new body of work by Namoda offers a prescient reflection on life experience, thresholds, and the passage of time in Africa, using tableaus and forms that weave narratives of magic realism into the verdant Mozambican landscape.

The following text, a close collaboration between Namoda and writer Wesley Hardin, offer viewers their first entry point to the exhibition. Structured as a short poetic narrative, the piece provides a thematic accompaniment to the works on display. And in so doing invoke you to commit, in the words of the authors, 'to the vital and inarticulable labor of reading.'

Pry closed eyes open and it's violet outside.

Not the colour, but the word, like one consonant—hardly a syllable—separates you from...

It spans across the earth and sky, the violet, in long lashes. From one horizon's end to the other, and impossibly narrow, like delicate capillaries, or the wisp of a bomber jet as small as a dragonfly. In Namacata, a boy awaits the lull of the afternoon when, upon turning his mind's eye from the world at hand, he can see the violet veins in the earth and sky. Eyelids heavy, he spots the first lash—it snakes through the ground beneath his bare feet, and beneath his mother's. Beginning at sunrise, she has spent the morning working this patch of land beside the river, cleaving its salty soils and mixing them with the contents of her pockets: grains, tubers, silt. But the afternoon is his, and with the exquisiteness of a spider at the loom, and the power of dreaming that belongs only to the late day's sun, he begins his work also.

At each end of the earth, just beyond the last palms and hills in sight, he imagines a great and crude iron spindle. Shetani spirits awaiting at lands-end pluck the veiny tendrils that hang off the edge of the horizon and begin to coil them around each iron, like a spool. With one great turn of the spindles, the violet lash beneath his feet is tightened at each horizon and sprung up from the ground, taut and resonant, to the level of his knees. His mother does not take notice, although she too is caught in the midst of a transfiguration. Where once her hands grasped a trowel's wooden handle, a joint is now fused; flesh becomes wood; wood becomes steel; she has transformed into a jet-black crescent, a sickle with a glistening grey tip. And with each downward arc of her great extremity, she no longer sows her grain, but instead gently strums the violet string that is stretched across the horizons.

'...to see many things.'

The sound that comes from the strum is one you've heard before and I won't bother to describe it, but other things come too. First, water, so clean and restorative that it erupts from the vein in diamond panes like glass, and can be chewed, savoured, and swallowed. Then ivory orchids in an unfurling carpet, trembling just like the ones the boy's mother had once shown him in the forest, at the base of a rotted ebony. His mother's mother emerges too, stepping out from behind a palm to assemble a fragrant bouquet for her grandson, her body unlike the one he had glimpsed in the wooden box, with dark hair and full breasts. Then a stream of dazzling earths: ruby, silver, mercury. And a songbird and a jade mountain and a trove of plastic toys. These are the other sounds of God's instrument...

'To live long...'

Awaken, again, and it's peachy outside. Not the word, but the colour—today, the clouds are the exact shade of palm flesh. A man stands among others in a river: in fact, it's the same river beside the boy and his mother, only so many countless measures downstream that it's become an ocean. He lifts his waterlogged hands to find deep, thrombotic creases and veins, and realises now that he's a man who's been wading in this river of an ocean for a very long time.

Prostration. Procession. Prayer. For all, it's a day of cleansing. But before he can leave the river he must spend a moment submerged beneath the waves. They take their turns. Prostration. Procession. Prayer. He's next. The priest raises his hands in sanctification and the air solidifies into wax.

'To live long is to see many things.'

There it is—the question that masquerades as an adage: And what of seeing? Or the question beneath the veil of the first question: And, if long lived, what of learning?

Derrida, in the grips of deathly illness: 'So, to finally answer your question, no, I never learned-to-live' (2007, The Last Interview, Jean Birnbaum).

Pry closed eyes open. Eyes open underwater to the cast of moonlight; the garoupa clings tightly to its babe. How might it taste, this delicious un-beginning like bubbles frozen in dandelion honey?; how sweetly it must feel to eschew the cradle that is also the first grave. Together, in the crevasse, beneath the river moss, before the world. This life, so strange and precious, is not unfamiliar to symmetries.

Or are you not, at this very moment, awaiting a similar deliverance?

[BRISKLY]

This'll pass.

This too shall pass.

'Has it passed?'

It passed.

It's in the past...

All's grist to the mill and then the world turns.

Press release courtesy Goodman Gallery.

163 Jan Smuts Avenue

Parkwood

Johannesburg, 2193

South Africa

www.goodman-gallery.com

+27 117 881 113

+27 117 889 887 (Fax)

Tues - Fri, 8:30am - 5pm

Sat, 8:30am - 4pm