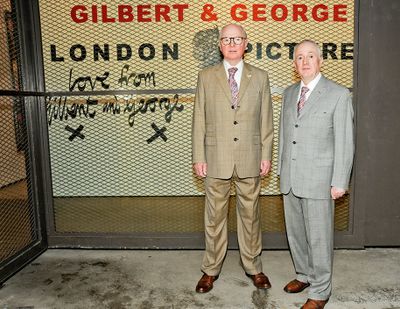

Gilbert & George

Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artists and Lehmann Maupin, New York/Hong Kong. Photo: BFA, New York.

Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artists and Lehmann Maupin, New York/Hong Kong. Photo: BFA, New York.

'Extraordinary!' is how George periodically punctuates his sentences, like a West Country boy still blinded by the city lights. Gilbert occasionally echoes him—his R's rolling off the Dolomites of his youth. Despite living in London's Spitalfields for half a century, no detail of urban life ceases to astound their collective curiosity. At once innocent and worldly, ancient and newborn, they seem as astonished as they are unfazed by whatever sight sears their conjoined retinas.

Indeed, the besuited lives of Gilbert & George are bound up in contradiction, and it is this defining feature that makes their work so compelling. Polite yet irreverent, regimented yet unruly, conservative yet deeply anti-establishment, these iconoclastic icons evade categorisation, which is ironic given the obsessive drive with which they attempt to archive the world around them. Like a scatological Mnemosyne Atlas—Aby Warburg's symbolic lexicon of reanimated classical imagery—their lifelong opus depicts grand themes, from theology and sexuality to patriotism and death, refracted through the microcosmic details of their ritualised daily lives.

I did not expect to like Gilbert & George. Even allowing for a hefty dose of irony, their political posturing struck me as flat-footed and arcane, while their Thatcherite brand of individualism remains anathema to me. But even a 'good leftie' like this one (thank you, George) can't help but admire their oddly framed quest for a democratised 'Art for All', and I respect their dogged defiance towards a liberal political culture that is often selective in its own commitment to such lofty ideals. Those of us who were privileged enough to receive a free arts education in the UK can look back on a golden age of access and opportunity, compared to the cascade of debt being inflicted on current cohorts. But 1960s Britain could be a pretty illiberal place too, in which the kind of grants and public funding enjoyed by subsequent generations of artists was simply unavailable to two gay men making objectless art. This hypocrisy irks them. As they proudly pronounce, 'We want our art to bring out the bigot from inside the liberal and conversely to bring out the liberal from inside the bigot.'

Ever the affable and courteous couple, what emerges from our conversation is an incandescent sense of purpose: a creative hubris that is as charming and disarming as it is myopic and obtuse; a butter knife-edge between the self-possessed and self-obsessed. And yet there's a tenderness and nostalgia that belies their outward conceit—in a simple description of the feeling of falling snow, or the forgotten lives contained within a chewing gum stuck to the street. For all their methodology and procedural dogma, Gilbert & George are quintessential romantics, now celebrating 50 years since first meeting in 1967 at St Martin's School of Art in London.

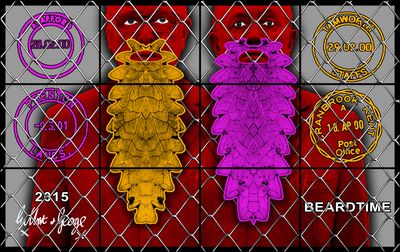

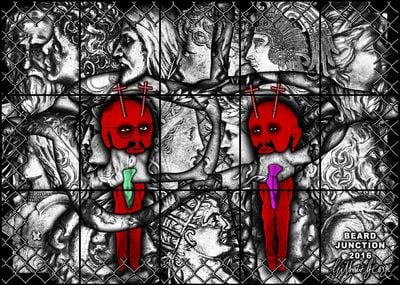

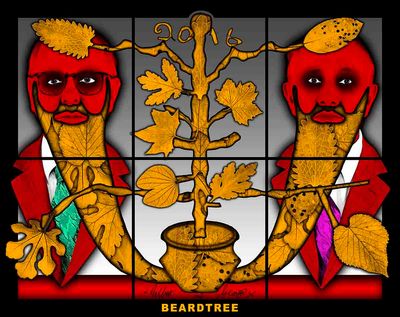

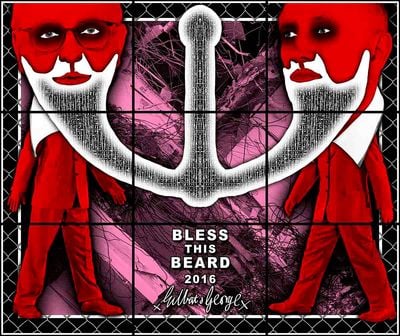

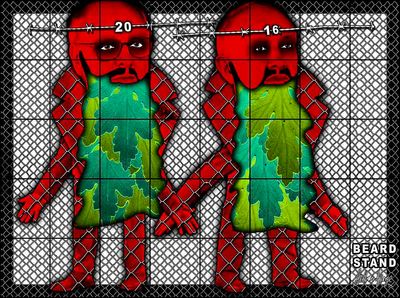

THE BEARD PICTURES at Lehmann Maupin, New York runs from 12 October to 22 December 2017. THE BEARD PICTURES AND THEIR FUCKOSOPHY is on view at White Cube Bermondsey in London from 22 November 2017 to 28 January 2018.

DBYou started out with The Singing Sculpture, a tableau vivant performance of Flanagan and Allen's duet Underneath the Arches, which you first performed as 'living sculptures' in 1970. Was there a moment after you started working together that you realised, 'this is us for the rest of our life'?

GGGeorge: From day one. It took over us. We didn't make that decision. It came over us like the changing weather. And, of course, because we weren't collaborating, the problem that exists with people who collaborate didn't exist for us. We were doing it as one artist.

DBDo you distinguish between your objects and your Living Sculpture?

GGGeorge: We feel they're all intertwined. We wouldn't see them as separated. People who have never been to see an exhibition of ours know something of what we're saying. It means something to them. It's not the form.

Gilbert: I think all the images become powerful. Even on a bus. People don't have to see the art. We create a kind of aura of—

George: Cultural ideas.

DBWhen you first came to London, did you find St Martin's School of Art a welcoming place?

GGGilbert: It was extraordinary. It felt like landing on the moon for me.

George: There's a little show in London of the first work we did when we came to New York, The General Jungle [The General Jungle or Carrying on Sculpting at Lévy Gorvy, 13 September–2 December 2017], and it has text on the bottom of the panels. One of the texts says: 'The total mystery of each man-laid brick.' And that's what we felt as country bumpkins coming to London. We'd see Euston Station, St Pancras, the Palace of Westminster, Charing Cross Road, Sloane Square. We still are amazed. All those basements, all those policemen, all those libraries. It's extraordinary, don't you think? What mankind did? And it continues. There's scaffolding all over the city as we speak. Extraordinary!

Gilbert: Not only that, an art school that was totally free. Not the whole of Saint Martin's School of Art, only the top floor: two rooms where artists and students were allowed to be totally free.

George: The advanced sculpture course.

Gilbert: That's it.

George: And it was free because Frank Martin, who ran it, had been in the Desert Rats, and he explained to us once why he ran the course as he did. It's because he had seen so much horror in the war that he thought people should come together. So when he ran the course, any student who applied, if they came from another country that wasn't on the course, he would take them in. 'Devon? Okay you can go in.' 'Oh, north of Italy? We'll let you in.' He thought that if all the students came from different places, it would be a good idea.

DBDo you think of art as offering a potential for catharsis? Is that something you see as one of art's functions?

GGGilbert: Yes. I really believe that.

George: We always say art deals with everything that's left over after the police station, the church, and the government. If you have a problem, if you break your arm, you go to the hospital. If you're robbed, you go to the police station. And if you're still not there, then it will be a book or a show or a gramophone record or something.

Gilbert: That's why people go by the millions to museums. They're all searching for themselves. They're trying to heal themselves, full of anxieties. Or because life is so boring. But it is a healing process, art.

George: We always say that somewhere on the clock—it doesn't matter where it is, in some distant city in another time zone, somebody's looking at a small painting by van Gogh and wondering why the trees are so gnarled. Still, it's speaking. It still means something.

Gilbert: And it's quite interesting because in some way art is still very primitive. It hasn't moved anywhere, from the first cave painting to the ones now.

George: Hunting and sex.

Gilbert: Hunting and sex. And that's quite interesting!

DBSince you had all this freedom at the top floor of Saint Martin's, did you feel lost when you left?

GGGilbert: Once they chuck you out, it's the real world. You have nothing any more. Before, we had a room to go up to; after that, you only had the streets of London. And that was the best idea! That we didn't have anything. We became it then. And for ten years, we did all our artwork in the kitchen. Ten years.

Gilbert: And that was the saviour of us—that we didn't have anything. That made us think differently.

George: Most students were part-time teachers before they even left college, to bridge the gap financially. Or they got a year in the English School in Rome, or you got a Gulbenkian Grant, or you got a subsidised studio from SPACE... None of that was available to us, even if we'd wanted it. We were only one year out of decriminalisation. Two applying for a job from the Greater London Council? An unthinkable idea.

DBOne year out of decriminalisation, but you found London a welcoming place?

GGGeorge: Wild, wild times we had!

Gilbert: Wild!

George: We'd go mad every night, we were crazy. All over the world.

Gilbert: London was extraordinary.

DBAre you still happily and productively lost, or do you feel found now?

GGGeorge: We want to win. We still don't feel we've won. That meeting we had in Italy recently ... We did an interview, and they were trying to understand why the artist does it. What is it? Is it a drive? Or is it a need? We gave some explanations and the audience all looked puzzled. And then we said, 'We do it because we want to win and be loved', and they all stood up and clapped. It was an extraordinary moment. And that's because it's what they want as well. Everyone. Or not?

DBCan you ever win at this game?

GGGeorge: We're still at it.

Gilbert: We can die!

DBYour current exhibition, The Beard Pictures, focuses quite literally on the changing face of your neighbourhood, from Bangladeshi shopkeepers to gentrifying hipsters. How has your own sartorial sensibility shifted over the years? At a certain time your suits would have spoken to establishment values; but now, for example, with the way Neoliberalism has appropriated a lot of the aesthetics of the counterculture, they read very differently from when you first put them on in 1969.

GGGeorge: We said that we never wanted to be normal because everybody is; and we didn't want to be weird, because all artists try to be weird. But we wanted to be weird and normal at the same time.

Gilbert: We had to remove ourselves to become visible. We wanted to be living sculptures, that's how we started out. Then we took it into the gallery; we became the centre of our art. That was the most important thing we ever did.

George: And it was like us, as poor boys, looking for a job. You always put a suit on if you apply for a job, or if you go to a wedding or a funeral. The suits are very much discussed within the cultivated art world; but outside that, suits are completely normal. When we walk the streets before breakfast everyone just says, 'Great suits, guys!'

Gilbert: They don't even have to know who we are.

George: Half the people who take photographs of us in the streets don't know that we're Gilbert & George, which is fantastic.

DBThey just think you're two well-dressed gentlemen?

GGGilbert: Awkward ones, yes!

DBI've heard you speak a lot about politeness, whether it's in the context of the press or elsewhere.

GGGeorge: Fucking press!

DBI'm intrigued by your embrace of politeness. I've always been struck by the way the British can be incredibly rude while maintaining a veneer of politeness. They're the masters of passive aggression.

GGGilbert: Brought up to be polite.

DBBoth in Italy and in England?

GGGilbert: Totally.

DBThat leads me to a broader question about your relationship to British class, which is such a specific and pervasive thing. Gilbert, you came from a family of shoe-makers in Italy, and you, George, came from—

GGGeorge: Darkest Devon!

DBAnd also from a single mother, am I right?

GGGeorge: Yes.

DBSo you, George, from within the British class system and you, Gilbert, from outside of it. How did you deal with class when you arrived in London?

GGGilbert: We never felt we had to deal with it in the art world.

George: Not in that sense, no.

Gilbert: I don't think there was ever a pressure.

George: Maybe because we always felt superior.

DBReally?

GGGilbert: We never had a problem.

George: We were both brought up to be better. The middle classes are not brought up to be better, but lower class people are brought up to improve themselves. We didn't have the safety net of the middle classes, as students—that was very important—who can go back and run Dad's pig farm or something. We didn't have that. We had to succeed or fail.

Gilbert: We had to succeed. We knew that we only wanted to be artists, and nothing else.

George: We have a term ... We talk about the frowning classes. They're the ones who might say 'Oh well you know that Gilbert & George, I'm not entirely sure of every single one of their ... I mean those excrement pictures!'

Gilbert: Sometimes we meet upper class people and we rather like them. They're more eccentric.

George: There are no frowning classes among the toffs. They're more open-minded and generous...

Gilbert: ...than the intolerable liberal.

DBWho always wears black?

GGGeorge: Exactly. Bloody Oswald Mosley blackshirts!

DBYou've said that you admired Margaret Thatcher greatly, that she did a lot for art, and that you're also fond of the Prince of Wales. What did they make of your work?

GGGilbert: I don't think they know anything about us, because we never went near them. We didn't ever feel we had to meet Prince Charles or the Queen or Maggie Thatcher. We're outsiders.

George: All lousy artists get invited to the Palace or to 10 Downing Street sooner or later, if you're bad enough. Really, if you take drugs and things.

DBBut when you say you admire them...

GGGilbert: I admire her because she changed England forever, Maggie Thatcher.

George: And not only England.

Gilbert: She arranged a free market economy that was not there.

DBSo is it the entrepreneurism that you admire?

GGGilbert: Yes.

George: All the artists caught on. They're Thatcher's babies, not us.

Gilbert: All the art world.

George: Though they don't like to be described as that.

Gilbert: All the galleries who made money came out of that.

George: We never met a person in another country who didn't dream of having Margaret Thatcher as their president or prime minister.

Gilbert: Whatever she thought of us, that's something different.

George: We don't care.

Gilbert: If the Queen likes or dislikes something, it doesn't mean anything.

George: We are subjects.

Gilbert: We are subjects.

George: It's not for us to have an opinion, like all these damn silly artists!

Gilbert: I mean Thatcher was anti-queer. But so are many others; 80 percent of the world is.

George: Roughly speaking, we support the Tory party because it's aimed at the individual, and the Labour party is roughly aimed at collectivism. It always goes towards that, even when they're both on the centre-right.

Gilbert: In the end, only the individual artist wins.

DBBut you both came from modest backgrounds, and I'm guessing you wouldn't have been able to afford the fees at Saint Martin's if you had to pay what this generation has to pay.

GGGilbert: I did pay. I paid 300 pounds at Saint Martin's School of Art. That was quite a lot of money, all my money in '68. And George, you had a grant, no?

George: I was really very lucky.

Gilbert: But you worked.

George: As well.

Gilbert: Non-stop, in the evening. Teaching hooligans.

George: It's not free. You can only have fees paid by a nation if the nation is very successful and making money.

Gilbert: But, I mean, we don't care. We always managed.

George: Self-supporting.

DBNothing from the state?

GGGilbert: No, nothing.

George: The Arts Council, British Council, nothing. Very few artists can say that.

Gilbert: Even institutions in England wouldn't buy our art for a long, long time. We had to travel the world.

George: To exist.

Gilbert: Even now we are still travelling the whole world non-stop, trying to sell our art.

DBWhat about the idea that capitalism gives an illusion of choice, but actually leads to the homogenisation of culture? We see that in every High Street in Britain. If I go up to North Wales it looks identical to a street in South London.

GGGeorge: Brick Lane's not like that. We just came back from Tasmania; Tasmania's like my youth. I know what you mean, though.

Gilbert: We never go to the West End. We have never gone into a big department store in 50 years, not once.

George: Artists can't be chain stores.

Gilbert: Well they are. That's why we try to keep outside with our art, our vision. We try to make a more personal art that's not part of the inner circle of art.

DBI wonder whether there's a danger of confusing equal opportunity with a levelling conformity?

GGGilbert: I never voted in my entire life. In the end, we only concentrate our vision through art. I think that's more important. If the Labour Party is in power, it's fine.

George: We took some of the best pictures under the Labour Party: the 'Dirty Words Pictures' (1977). Fuck, Dick, Shit, Lick.

Gilbert: We want to be individualists and we think collectivism and the Labour party, even now, especially now ...

George: The dream of the Labour Party is that the artist will sell works at a reasonable price to hospitals. And they do, the artists. They're queueing up to sell to those hospitals. Even if we wanted to sell to a hospital they wouldn't buy us. They wouldn't even accept them as gifts.

DBI'm interested in the systematisation in your work, this drive to keep things ordered. A lot of very busy people, high achievers, try to limit the number of daily choices they make—what socks they wear, what breakfast they eat—because it allows them to focus their creativity on the things that matter, on their work. But I know that you carry your systematisation over into your work as well. It's about the way you choose colours, the way you choose images, and that categorising impulse.

GGGeorge: It's very simple. If we're totally madly over-organised and regimented, we can be nuts in our pictures. But if our life was all confused and elaborate and complicated, we wouldn't have any empty head left to create a tree in. We need the simplicity.

Gilbert: We've never boiled an egg in 50 years.

George: No kitchen.

Gilbert: And we only make instant coffee. Water and instant coffee, it's all we have in our house.

George: The freedom of the head that we have is extraordinary.

Gilbert: We buy things that last maybe one year.

George: A dozen catering tins at a time.

Gilbert: A year of toilet paper. And we have seven shoes, and they're all exactly the same. One in, one out, one in, one out. So we never have to go to the cobbler, except maybe once a year.

George: They all wear out at the same time!

DBSo when you say that by simplifying your lives it allows your paintings to be nuts, am I right in discerning a distinction between the content—which, to use your phrase, is nuts—and the way you make it, which is very ordered?

GGGilbert: There are two parts that are very important. We have the period when we're taking the images—the research, we call it. And that could be maybe two or three months when we are trying to find out what our new interests are.

George: Without being too conscious.

Gilbert: We take maybe 10,000 images before starting to do designs.

George: We're looking for the moral dimension. We don't want an image just because it's nice or interesting or strange or mysterious. It has to have some actual human significance.

Gilbert: It has to ask questions: that's very important, and it has to disturb in some way as well. We want them to be pictures that maybe a collector likes, but will never take home. We like it when they run away from our pictures. That's quite good as well.

DBDo you consider your work shocking? How important is shock as a tactic?

GGGeorge: We never set out to shock. We wouldn't do that. I mean we're more shocked by the news every day than any art that we've ever seen. I don't understand why they're allowed to show 300 Hutu people floating down a river dead on the national news, and then say: 'Now we'll move over to the sports.' We're deeply shocked; we think that's horrific. And that's all the time, you know? A volcano eruption one day, a flood the next, wildfire.

DBDo you think about your work in the context of movements that were shocked by, for example, the slaughter of the First World War? In the context of, say, Dadaism or Surrealism?

GGGeorge: Not in terms of the art, no. I think we deal with the issues of war. I mean, we are war babies... But we don't have a favourite artist history, or stuff like that. We were socially involved with artists for a while in London, Paris, New York and Düsseldorf a lot; and they always talked about artists. We called it foreign wanking, always looking up to some dead foreigner. And we used to tell them, 'Those artists probably weren't anywhere near as good as you.' They suffer from adoring the expensive dead artists, and we always promised ourselves never to do that.

Gilbert: We made a very big point that what we do is ours, without looking to other art.

George: Art about art was the disease of the 20th century. Every artwork refers to some other.

DBReading about your process of working—of taking photographs and categorising, filing and archiving them—brought to mind Aby Warburg and his Mnemosyne Atlas. What criteria do you use in your own mind when you're archiving photographs?

GGGeorge: I think it's what we were saying before: it's the moral dimension. The most simple example is this. For years, we took images of the chewing gum on the street. It's very difficult to take them, because if it's completely dry, you can't actually see the dirt that's in the cracks. It's just a blob. And they only get dirt in the cracks when it rains. But if you take them then they're all shiny, it looks like a glossy nothing. So you have to wait for the rain to come, and then for the gums to dry, but not be too dry, and take them then. So we took them, and the next year we took some more. And we still didn't know why we were taking them, and that's why we didn't use them.

Then one day we realised that every single chewing gum comes from a certain individual person. They may be in prison, they may be dead. I'm assuming many of them are dead, as gum lasts for 20 years. Maybe that person was in love. It's extraordinary to think that every one of those has an amazing story. There's nothing that's not in a chewing gum.—[O]