Hetti Perkins Introduces the 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial

Hetti Perkins (Arrernte/Kalkadoon peoples), in front of Uta Uta Tjangala (Pintupi people), Untitled (1984). © Estate of the artist. Licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd and Doreen Reid Nakamarra (Pintupi people), Untitled (2005), National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra. © Doreen Reid Nakamarra/Papunya Tula Artists/Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

Hetti Perkins (Arrernte/Kalkadoon peoples), in front of Uta Uta Tjangala (Pintupi people), Untitled (1984). © Estate of the artist. Licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd and Doreen Reid Nakamarra (Pintupi people), Untitled (2005), National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra. © Doreen Reid Nakamarra/Papunya Tula Artists/Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd. Courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

In August 2020, Australian writer and curator Hetti Perkins was appointed as the curator of the 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial: Ceremony (26 March–31 July 2022).

Since, Perkins has navigated lockdowns, delays, and Zoom studio conversations, taking the time over the last two years to build on informal relationships with artists and listen to stories from multiple Indigenous communities around Australia.

At its core, Ceremony embodies 'personal acts of faith, intimate rituals, [and] mass protests'. It is testament to the survival of Indigenous peoples' land and communities, their tenacity, and capacity for innovation and adaptability.

First shown at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, the Triennial will travel to the Samstag Museum of Art, UQ Art Museum (19 August–26 November 2022), followed by Shepparton Art Museum (18 December 2022–26 February 2023), ensuring audiences from different states in Australia can see the exhibition.

Thirty-five cross-generational artists—with 16 drawn from collectives—have been selected for the exhibition, none of which have been included in past editions. Perkins has also invited local Ngambri-Ngunnawal custodian Elder Matilda House and her son Paul Girrawah House to realise a public installation of traditional Aboriginal tree scarring in the sculpture garden, which will remain on permanent display at the National Gallery of Australia.

Prior iterations of the Triennial include Defying Empire (26 May–10 September 2017), by curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the National Gallery of Australia, Tina Baum (Larrakia/Wardaman/Karajarri peoples), unDisclosed (1 May–22 July 2012) by Carly Lane (Kalkadoon peoples), and the inaugural Culture Warriors (13 October 2007–10 February 2008) by Brenda L. Croft (Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra peoples).

During this year's exhibition, one of Australia's enduring protest actions, the Tent Embassy, will celebrate its 50th anniversary. As a symbol of Aboriginal protest for sovereignty and the right to self-determination, the legacy of the Tent Embassy continues to assert the inalienable connection of Aboriginal people to Country.

Perkins draws direct influence from this event, as well as her childhood in Canberra, where she witnessed fervent activism, the formation of her mother's garage gallery, and the creation of Lake Burley Griffin in 1963, which lamentably caused a ceremonial ground to flood near the National Museum of Australia.

As the oldest daughter of renowned activist and soccer player Charles (Charlie) Perkins, Perkins began her career at the Sydney gallery of Aboriginal Arts Australia working with artists in remote and rural community centres.

Soon after, she joined the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative as curator, whose founding members included Fiona Foley, Tracey Moffatt, Brenda L. Croft, and Michael Riley, among others.

Since 1987, the Co-operative has formed a unique space within the arts ecology to support, promote, and protect future artists, and challenge preconceptions around urban-based Aboriginal art.

Between 1989 and 2011, Perkins worked as senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. During this time, she curated major survey exhibitions of Indigenous art, including Australia's representation at the 1997 Venice Biennale (15 October–17 November 1997), alongside Brenda L. Croft and Victoria Lynn.

Since starting her career, Perkins has published extensively on Aboriginal art, co-editing Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius (2000) with Hannah Fink, and Crossing Country: The Alchemy of Western Arnhem Land Art (2004), both released in conjunction with exhibitions at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Perkins has also produced the renowned ABC T.V. series, art + soul, in which she travels to Australia meeting artists in their homes, studios, and on Country, often with their family and communities.

In this conversation, Perkins speaks with Australian writer and curator Natalie King about the concepts behind Ceremony, her childhood musical inspirations, and how biennials and triennials bring wider recognition to local artists today.

NKYour curatorial statement is presented as an open letter, which is a tender and intimate way to prepare a curatorial concept. How did you arrive at the idea of the open letter?

HPThe open letter was originally for Artonview, the National Gallery's magazine for their members. It's an informal and rather ambiguous way of presenting the show, which offered people a platform to freely interpret the concept of 'ceremony'.

Ceremony can be enacted in all ways: in private, performed in the studio, the home, or in someone's mind; or it can be a public participatory process. The Tent Embassy in Canberra, for instance, incited a demonstration as a form of ceremony, with its own set of protocols defining who has the authority to talk, while reflecting a community working together in shared aspiration.

NKIs the letter addressed to your community, your family, or the artists?

HPPeople often come to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art with preconceptions about what they might see. The letter is an appetiser for works that they might either find unexpected, or relational. Works that relate to other Aboriginal artists' works across the country, regardless of what medium they're working with.

NKHas the concept of 'ceremony' been percolating for a long time? How did you come to this as a framework?

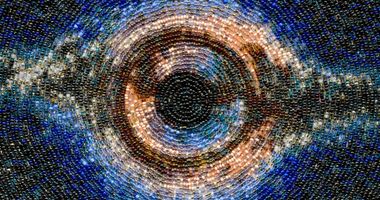

HPI've been interested in the idea of iteration. When you iterate something, you can enter a different internal state, like a ritualised protocol achieved by saying or doing something again and again.

It's an interesting way of understanding the space artists go to when they create a work. Watching some artists paint in the Western Desert, I felt like something was being channelled through the artist's body into the work and cycled back again.

The key idea with many ceremonies is that they are regenerative, healing, and continuous. I wanted to highlight that the art being made today is still grounded in the concept of ceremony, in addition to Country, culture, and community. It's a point we need to reiterate, even after all this time.

After invasion, we can carry on and flourish, maybe go in different directions, while being a part of what has come before.

Incidentally, I also began to think about the Joy Division [New Order] song, 'Ceremony' (1981). Growing up and going to school in Canberra, that kind of music was a very big part of my life. Although Ian Curtis, the lead singer of Joy Division died in 1980, the band had already made a provisional recording of the song, which became New Order's first release. After this cataclysmic event, something new was created that was a part of the old.

NKThat's a beautiful connection relating to an anthem from your own history in Canberra. It's like a soundtrack from different parts of your life.

HPCertainly, Joy Division, and that kind of music, was very big in my life growing up in Canberra. I found that sort of protest, anti-establishment-esque music was very relevant, alongside more expected anthems like Warumpi Band and Midnight Oil songs, whether it's part of the Aboriginal rights movement or nuclear disarmament.

NKSongs can also be thought of as spoken word poetry or activist poetry, which is so important. I think of Romaine Moreton and how words can be defiant.

HPLanguage is very important. One of my original ideas was to have a concert, a choir of sorts, like a sing-in, because sound can penetrate past cops and through walls to get a message across. We have an amazing history of protest music in this country by Australian artists such as Yothu Yindi, Midnight Oil, and Col Joye.

NKCan you elaborate on your personal history in Canberra alongside the legacies of activism and the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in the city? How have these informed the project?

HPI wasn't born in Canberra, but we spent a lot of time there. My dad, Charlie Perkins, worked there because he wanted to be close to the heart of political power. There wasn't a separation between the personal and the political in our family.

Ever since I can remember, I've been going to demonstrations and meetings, not knowing what people were talking about necessarily, but just being part of that world. It's something that was very normal for us.

Mum was pregnant with me when Dad was on the Freedom Rides [protests in Southern America in 1961 contesting segregated bus terminals]. Politics and activism have been an intrinsic part of my life, and my siblings'.

Mum also had a little gallery in the 1970s in Canberra, held in the garage under our house, because there was no National Gallery. I think she converted the garage into a gallery space because she wanted us to have that cultural context, not just our particular cultural heritage, but Australia's more widely.

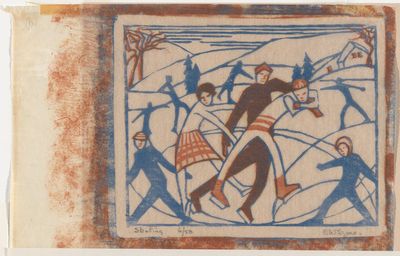

I was only ten at the time, but I spent a lot of time in that space looking at beautiful paintings—Papunya boards, bark paintings, and amazing weavings—all the incredible things that were being made around that time.

I was around the Tent Embassy protest site when it was established 50 years ago. There were lots of protests and demonstrations then, including the one on what is now called Capital Hill, where the new Parliament House is.

When I first asked artists to participate in the Triennial, I gave them a couple of sentences about what ceremony means to me, including the following words: active, activate, activists, as well as the idea of iteration.

The show is in Canberra, on Ngambri and Ngunnawal country, which is a politically contested place many of the artists have never been to, despite being the place where decisions affecting their lives are made, like The Intervention [policies enacted on Northern Indigenous land that impacted welfare distribution, health services, and education] and land rights protests.

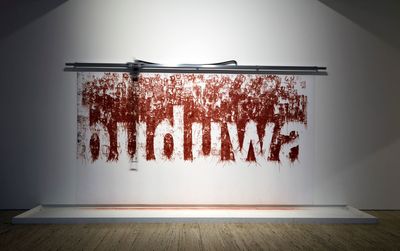

Yarrenyty Arltere and Tangentyere artists from Alice Springs are presenting a soft sculpture version of Parliament House—a black Parliament House complete with a coat of arms and placards.

Another significant work is by Dr Matilda House and her son, Paul Girrawah House, who are doing the tree carving project on the gallery grounds, with a view to extend the work's reach to include the Parliamentary Triangle as a marker of local custodianship and local lore.

The National Gallery of Australia is right next to Parliament House and the High Court as part of the Parliamentary Triangle, which has its own governing authority. Coincidentally, I grew up with Aunty Matilda who was a very good friend of my dad's. I went to the same school as her kids which is a nice personal connection for me.

NKIt seems important to show in and beyond museums, as an enduring legacy.

HPYes. It is a wonderful legacy project because the lake isn't real and was created in 1963 and flooded a ceremonial ground, where the museum is located.

NKCan you elaborate on some of the key commissions and dialogues that you might be setting up? Are you clustering works, or thinking of presenting particular artists side-by-side?

HPI was very keen to resist the idea of a 'National Indigenous Art Triennial', as I did not want it to be a traditional survey show. I wanted to see how this edition could respond to the previous ones and stake its own claim.

Some artists had never been to the National Gallery, much less had their work shown there. Some had never been to Canberra.

I began with the premise to only include artists who hadn't been in previous editions. I was very keen to invite artists whose work had struck a chord with me in some way, but also works that really showed the breadth of 'ceremony'.

Nicole Foreshew, for instance, wanted to work in memory of a late artist from the Warmun community who was a mentor and collaborator. The two had formed a friendship, an alliance of sorts, that was very much cross-generational and cross-cultural.

As the older lady has passed away, in some ways, this is a chapter in that story by including the work of someone posthumously.

Hayley Millar Baker's film, on the other hand, is a cinematic work featuring Hayley herself, but also a portrait of the world inside her head: the things she experiences and the personal, intimate, and domestic rituals she maintains in terms of her engagement with the spirit world.

Gutingarra Yunupingu is a young Dhuwala filmmaker. He works in Yirrkala but his homeland is Buymarr. He's presenting a work about his identity as a saltwater person and representing himself as an ancestor being within the saltwater Country.

Dylan River, who is also a filmmaker, is presenting a large-scale photograph revolving around the Old Telegraph Station in Alice Springs, which was a half-caste Aboriginal children's home, where his grandmother was brought.

Policies like removing children from native camps and their families have impacted the transmission of culture across generations. Dylan's work overcomes that, while still connecting to the essence of 'ceremony'.

NKHow did you conduct your research, given the limitations of Covid on mobility?

HPI happened to be in Alice Springs just before everything shut down. I was visiting Kunmanara Carroll, who has since passed away; his family provided permission for his work to be shown in the Triennial. Otherwise, I relied on Zoom, informal telephone conversations, and building a really strong network to ease the stress everyone was already feeling.

Some artists had never been to the National Gallery, much less had their work shown there. Some had never been to Canberra. I tried to create a sense of cultural safety while staying open to innovative ideas.

NKYou establish informal relationships and trust with artists, while working with a large, hyper-regulated institution. How do you navigate that and advocate for the artist?

HPAs curators, a lot our work is a duty of care for others. Our role in many ways is to be a buffer. We filter some of the challenges to protect the artists and their creative space.

The event is held in Canberra, so it's even more bureaucratic, being so close to the heart of white government and a colonial administrative system. We tried to create a space for artists to feel comfortable, as it is not an easy place for them to speak truthfully and unfiltered.

Rather than commissioning individual writers to write about the artists' work, I thought we would produce interviews to include the artist's voice. It's such a privilege to be able to have these conversations and share them. Who better to explain what ceremony means to people and allow audiences to gain a depth of understanding than the artists themselves?

We're talking about turbulent times. For Indigenous people in this country, it's been turbulent centuries.

We filmed with artists where we could. Others, we haven't been able to access because of border closures, which is quite sad; I really wanted to visit and was looking forward to going to Milingimbi Island and other places.

NKWhat is your perspective on biennials and triennials, given that you curated the Australian Pavilion at the 47th Venice Biennale, and there's hundreds of biennials and triennials in Australia and internationally?

What do you think the role of a triennial is, and how do you think the National Indigenous Art Triennial sits in that ecology?

HPWe don't look enough at our own region, not only the First Nations, but our Pacific First Nations family. There's not enough recognition of those amazing artists, and that we are part of this place, the world, and this country.

NKThe whole solidarity between artists, communities, and First Peoples.

HPIt's difficult for First Nations peoples to do their own thing, because most are struggling to get by. Opportunities to work outside the mainstream are rare when the artists belong to communities that, through colonisation, are not well-resourced to do things independently.

I think art is generally under-resourced. Everyone I know is doing it for love, not money.

NKWhen I think of ceremony, I think of bodies, rituals, and performances. Are you planning any performances?

HPYes. Some will be filmed, or on film. Dancer Joel Bray, for instance, is creating a film. For the opening weekend there are a few things that we have yet to confirm. It will probably depend on Covid travel restrictions. Otherwise, with the Ngambri and Ngunnawal House family, we've been speaking about ceremonial opportunities available in addition to tree scarring.

S.J Norman will perform his work for a short period following the opening in Canberra. Robert Andrew will also install one of his writing machines, which is about ten metres long.

NKYou have written about the notion of 'radical agents'. How do you understand the concept of agitating within institutions?

HPPeople working inside institutions or mainstream culture can be radical agents within organisations; things change when the status quo or the D.N.A. of how we think, act, or appear changes.

There are different forms of activation, coming back to the Tent Embassy and what Canberra means.

NKWould you say there is an underlying sense of hope or restoration?

HPThe fact of survival is hopeful. Our culture has been key to our survival and has sustained us. However, the threat of climate change to our country—and to us—doesn't make me feel hope. We're talking about turbulent times. For Indigenous people in this country, it's been turbulent centuries. —[O]