Sheelasha Rajbhandari and Hit Man Gurung take Nepal to Venice

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH the 4th Kathmandu Triennale

Hit Man Gurung and Sheelasha Rajbhandari. Courtesy the artists.

Hit Man Gurung and Sheelasha Rajbhandari. Courtesy the artists.

Curated by artists Sheelasha Rajbhandari and Hit Man Gurung, Nepal's very first appearance at the 59th Venice Biennale (23 April–27 November 2022) extends the project of the 4th Kathmandu Triennale, co-curated by the artists to expand Nepal's engagement in global discourses.

The Kathmandu Triennale followed the Nepal Art Now exhibition at the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna (11 April–24 November 2019), which included works by Rajbhandari and Gurung, who are also the founders of the artistic collective ArTree Nepal, which has supported local Indigenous practices since 2013—ones that have been difficult to preserve in the face of colonial histories and globalisation.

But while the Kathmandu Triennale brought together diverse artistic languages and placed equal emphasis on both new and traditional practices from across the world, Nepal's first pavilion challenges cultural misconceptions that have portrayed Nepal and the Himalayan regions as 'a mythical utopia, shrouded in happiness'.

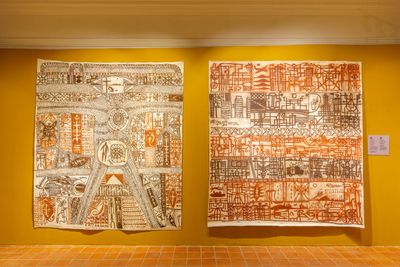

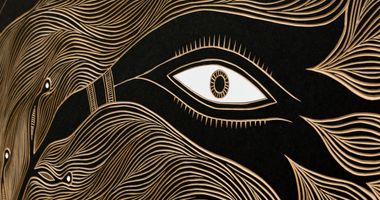

Titled Tales of Muted Spirits – Dispersed Threads – Twisted Shangri-La, works by Tsherin Sherpa, made with local Nepali artists, tell the stories of displacement and loss within local communities, and echo Sherpa's experience as a trained Tibetan thangka scroll painter whose subsequent move to California embodies a rupture with tradition.

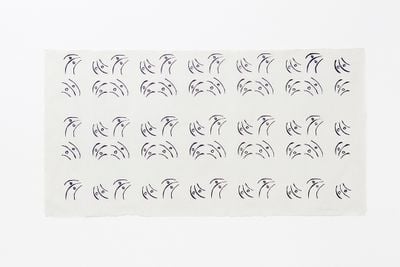

Rajbhandari, who trained as a sculptor working with techniques ranging from lost wax casting to stone carving, initially explored how the meaning of individual ideas and collective symbols change when placed in alternative contexts, before shifting her attention to social and environmental developments in Nepal with the onset of globalisation and cultural transitions.

With equal emphasis on the composition and decomposition of place, Gurung's documentation of the lives of Kathmandu residents traces shifting habits and customs with the onset of environmental pollution, mass migration, and consumerism, expressed across painting and the occasional performance.

Tapping into Rajbhandari and Gurung's existing interests in urban development, mass migration, and historical and geopolitical articulations of Nepal and its surrounding regions, the Nepal Pavilion conceives of its presentation in the context of former colonial influences on the region, which have disrupted local artistic and spiritual traditions by emphasising their potential as consumer goods for international trade.

In the following conversation, Rajbhandari and Gurung talk to Kathmandu Triennale artistic director Cosmin Costinas about their artistic practices, the collective effort behind the 2077 Kathmandu Triennale, the importance of reframing Eurocentric discourses, and Nepal's first pavilion in Venice.

CCCould you introduce yourselves? How did you become artists and where did you train? How have your practices evolved up to this point?

SRI trained in Nepal and am based in Kathmandu. My longitudinal research repositions quotidian and plural narratives by weaving folktales, oral histories, and performative rituals to juxtapose conventional historiography. This is rooted in the experiences of women and seeks to confront how female agency and corporeality become contested political sites for contemporary nation states.

HGMy works are concerned with the political, economic, and cultural forces transforming Nepal's physical and societal landscapes. I was born in Lamjung in Nepal and am now based in Kathmandu. I am particularly interested in the experiences of war, revolution, migration, and dispossession that have shaped the experiences of Nepalis across the world.

SRWe have actually been collaborating with each other since we were students in art school. In many ways, our practices and lives were affected by the political transitions in Nepal over the past three decades. We also felt very alienated by the vision of artists as limited to their studios. And as Indigenous artists, we were even more interested in exploring how to contextualise a history that was truly absent from Nepal's institutionalised narratives.

HGSuch themes also took a more concrete shape in our collective ArTree Nepal, which was founded in 2013. We continue to make art and build a community rooted in our political, ancestral, and Indigenous convictions.

CCIn your practices as artists, you have worked with Indigenous and feminist issues for many years, really trying to bring these perspectives into the conservative environment in which you are working. How does this translate into your work as curators for the Kathmandu Triennale 2077?

SRThe Kathmandu Triennale is an extension of our personal experiences. It is rooted in our relationship with various artists in Nepal and the work we've been doing for years, not only in terms of exhibition-making or production, but building a community and ecosystem dedicated to researching, observing, contextualising, and understanding the fabric of society. Such intersectional efforts were difficult to coordinate in the past—in many ways they were almost forbidden.

What we are taught by schools, the narratives propagated by our government, and the information circulated publicly are often refracted through a nationalist, patriarchal lens. In Nepal's context, it was only in the aftermath of the decade-long People's War (1996–2006) that we truly began to reposition and unravel this complexity.

It was a lot of learning and unlearning. This Triennale, the things we are talking about, and the people we are collaborating with are just part of a larger, ongoing, and perhaps never-ending process.

HGIt was also a strategic, political decision to bring together this exhibition as a collective movement. We were looking beyond singular, formalised practices, and intentionally incorporating a wide array of artistic lineages that survive despite being overlooked and undermined in readings of modernity.

There needs to be a decentralisation and deconstruction of all kinds of monolithic, homogenising interpretations of artistic traditions, which have heretofore been dominated by a myopic intellectualisation of what constitutes art.

CCDespite Covid-19, we've managed to do a lot of research together for the Triennale in different parts of Nepal. How do you think that translated into the exhibition and what kind of lasting impact do you think it will have on the realm of art after the Triennale, in the Nepali context?

HGOur plans were more ambitious. We were invited as co-curators in 2019. After the onset of the pandemic, we had to do some serious rethinking and scale down some of our goals. In Nepal, luckily, we had moments of respite when the lockdown was eased and we were able to travel to different parts of the country to meet community members, activists, artists, and friends who were all so instrumental in shaping the final form of the exhibition.

SRAgain, much of it unfolded organically. We tried to understand what the community sees or values rather than imposing our own perspectives. We also wanted to simultaneously challenge the projections of Eurocentric canons and the recent nationalistic historiography of Nepal's past.

It was a question of bringing in all this diversity, which has been historically and strategically marginalised. Because of Covid-19, initially it was challenging to re-orient ourselves. It did however give us time to rethink and communicate with the artists, as well as our internal team. It felt like a string of time that kept on elongating.

HGAlmost a week after the opening, more than 2,000 people were visiting the event every day, and many from outside Kathmandu. We feel that partly due to our prolonged engagement, the Triennale became a platform to express our solidarity and intertwine many discourses that were mostly being observed as independent and isolated phenomena.

CCI would like to insist on two things you mentioned. First is the question of the team—the way the Triennale was produced, installed, and manned was quite different from other international events.

The organisation was impeccable; artists felt like their work and time were respected, everything was installed at very high standards, and on time. The team was duly acknowledged and felt like they were a part of this effort. They were very much present in the exhibition, even after it opened, during guided tours, and so on.

Would you like to elaborate on the importance of building these relationships?

SRWe were really conscious about translating our artistic or curatorial intent within our management and having diversity within the team. Our personal experience as artists, within Nepal, and with previous engagements with international festivals also contributed to this dynamic.

To be frank, working in such large-scale productions is often unpleasant and rather toxic, especially for those who come from marginalised socio-economic backgrounds, so we were conscious about how not to repeat that.

HGWe value the team, so we prioritised fundraising for them in 2019. Team members are often relegated to handling production or logistics, but we wanted them to be involved intellectually and their inputs were important. We tried to facilitate a dynamic that fostered a shared sense of ownership and responsibility for our work. We also had a diverse team representing many Indigenous communities.

SRIt is important that the entire artistic ecosystem grows, and not just a single institution. There was a lot of invisible labour on our end, but we tried to make sure that everyone felt comfortable. Our curatorial team was also trained in different fields such as film, art history, anthropology, and journalism and their contributions added further depth to contextualising the nuances of each artwork.

CCYou also mentioned the Triennale visitors. What do you think the visitorship will be, and what kind of impact do you think the exhibition will have on them?

Could you speak about the different strategies we had in mind so that the exhibition would not only address a narrow cohort of privileged, urban, middle-class folks?

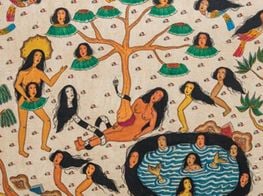

HRIn Nepal, art was for the most part patronised by the elite or ruling classes and enjoyed by few, so the effort is also to make different communities feel like they belong in this space. And such communities have continued to persevere and sustain lineages of traditions that have now come to represent their struggles for liberation, be it through tattooing, wooden carving, poetry, textiles, or film.

We are not just isolated beings in different parts of the world. There are connections and similarities between people despite the presence of constructed borders and political differences.

SRWe already see that a lot of our visitors are not from the obvious crowds generally seen at exhibitions. Another thing people mention is how relatable the exhibition is and how they feel valued after seeing it, because they don't feel like their experiences are represented in mainstream media—their voices have mostly been silenced.

It's satisfying to get that kind of critical feedback from viewers. People also visited multiple times, often bringing along their families and friends to share what they saw and felt.

CCBoth of you have also travelled, worked, and exhibited internationally. We're in a moment of deep crisis for our understanding of global solidarity and the ideas we had about an international art world as a place to contest aspects of global society that were built within it are being severely questioned.

The current war is seriously threatening the idea of global exchange, accelerating towards an apocalyptic scenario of a global war—it's painful to say this would be the best-case scenario, this isolation of the different parts of the world.

How do you think the propositions of the Triennale, with its particular strategies of decolonisation and ways of bringing together different contexts in the world, would function in this rapidly changing international context?

HGIn many regards, most Indigenous and marginalised groups around the world have struggled with wars waged by those in power for millennia. Our and their communities have always been victims of this untenable, authoritarian system and power game. Solidarity in this light needs to be invested in dismantling the illusions of empire in all its manifestations.

SRI think we are living in a time of transition where the illusion that we, as humans, are progressively developing into modern civilised beings is clearly breaking apart. We are also being pushed into a corner to choose different sides of the same coin. It's about time we not only question or critique but replace the problematic systems within which we function.

We are not just isolated beings in different parts of the world. There are connections and similarities between people despite the presence of constructed borders and political differences, which, of course, are rooted in colonialism. We want to at least start building a solidarity in which we can imagine our collective future, where we can imagine ourselves thriving, rather than it leading to a dystopian finale.

CCWhen thinking about the public programme that has unfolded through the Triennale, and the conversations it has ignited, what afterlife do you imagine this Triennale in particular will have in Nepal and your own practices, for example through your collective ArTree?

SRMost participants in the Triennale are representing their own communities or sharing their own voices and experiences. We wanted marginalised voices and communities to reclaim their own narratives—it's inherently counter-institutional.

For us, Nepal's participation in Venice results from many years of under-appreciated labour by numerous artists.

Many of the individuals and groups we were working with, the Karnali Arts Centre, Indu Tharu, Bhakta Bahadur Sarki, and Sanghari Sanskritik Pariwar, have practiced independently outside the purview of Nepal's formalised art scene.

They are thriving despite economic and political pressures; in a way their afterlives have always existed independently of the Triennale. We did however bring together and acknowledge these diverse threads that were related but dispersed.

HGArTree is also focused on a collective Indigenous experience, and we hope that through our various engagements, we are able to intervene in the macro-level forces and conditions that shape our lived experiences.

Often we do not have the resources or spaces to talk to each other about how to move beyond our history of marginalisation. We hope that post-Triennale, we are able to sustain the rich conversations that have opened up about queering bodies, futurisms for Adivasi and Janajati communities, and a cosmology that is infinitely complex.

CCBoth of you will be continuing your curatorial careers by organising the first Nepal Pavilion in Venice this year.

Could you talk about your plans for the pavilion, how you have been working with artist Tsherin Sherpa, and how you think Nepal's participation in the Venice Biennale will impact your artistic practices and the Nepali art scene?

HGWhen we analyse the realities of the contemporary art world, which is always dominated by certain power structures, artists from places like Nepal are always left out from larger global networks and discourses. Even when we speak of inclusion in the art world, often it is only limited to tokenisms.

For us, Nepal's participation in Venice results from many years of under-appreciated labour by numerous artists. It is an opportunity to present how, over centuries, we have managed to sustain, transfigure, and extrapolate our traditions in ways that do not fit neatly into taxonomies fashioned by the West.

SRFurthermore, in times of rising nationalism around the world, it's also a time to re-evaluate the very idea of nation-building and nationalism. What does it mean for communities that have been nomadic and navigated boundaries for hundreds of years?

Tsherin Sherpa as an artist embodies such fluid negotiations of identities that are also reflected in his works. Venice will be a small attempt at debunking the imposed gaze in which the broader Himalayan region has been packaged as a romanticised landscape of spiritual wealth.

We are also looking forward to the possibility of collaborating and building networks with like-minded artists and communities rooted in ongoing efforts of decolonisation. —[O]