Yuki Kihara's Paradise Camp

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH New Zealand Pavilion, 59th Venice Biennale

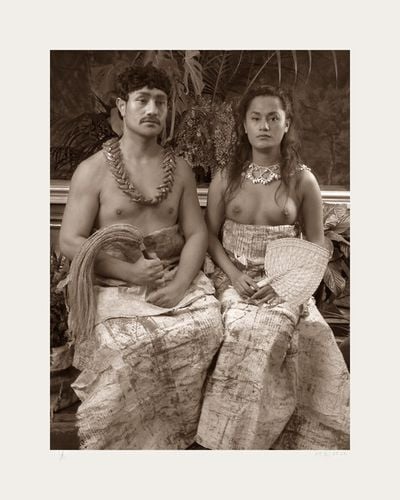

Yuki Kihara. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Evotia Tamua. Aotearoa New Zealand.

Yuki Kihara. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Evotia Tamua. Aotearoa New Zealand.

Sāmoan-Japanese interdisciplinary artist Yuki Kihara is immeasurably creative and unassailable in addressing some of the most urgent issues of the times—the environmental crisis, Indigeneity, and intersectionality—with exceptional flair, rigour, and humour.

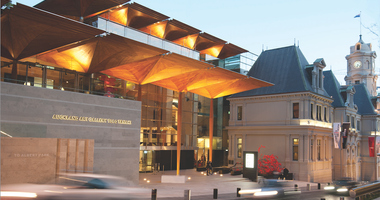

In September 2019, The Arts Council of New Zealand announced that Kihara would represent the country at the 59th Venice Biennale (23 April–27 November 2022) as the first artist of Pacific descent to be selected. New Zealand has been presenting at the Venice Biennale since 2001 with artists including Michael Parekowhai, Lisa Reihana, and more recently, Dane Mitchell.

Kihara declared: 'The glass ceiling has been shattered. This moment is so much bigger than me, especially for the Pacific art community. I am humbled by this opportunity and the platform that enables me to further amplify my practice.'

Kihara is Sāmoan and identifies as Fa'afafine, translated as 'in the manner of a woman', Sāmoa's third gender community to which she belongs. In 2008, Kihara had a solo acquisitive exhibition Living Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (7 October 2008–1 February 2009), where she saw for the first time paintings by Paul Gauguin.

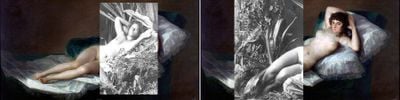

Recognising aspects of herself and the Fa'afafine community, Kihara formulated the concept Paradise Camp, an ensemble exhibition of three parts comprising 12 luscious photographs, an archive section of research images, and a single-channel video—First Impressions: Paul Gauguin (2018), in which a group of Fa'afafine discuss Gauguin paintings with hilarity, as they have essentially never heard of him.

Paradise Camp is further inspired by an essay titled 'He Tangi Mo Ha'apuani: Gauguin's Models – A Māori Perspective' by Māori scholar Dr Ngahuia Te Awekotuku MNZM presented at the Gauguin Symposium in 1992, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

In her paper, Te Awekotuku discusses how Gauguin deliberately painted his models to appear androgynous and exotic as a reflection of his personal and sexual fascination with the Māhu—the equivalent of Fa'afafine within the Indigenous culture of Tahiti, as described in his journal Noa Noa.

Kihara's Paradise Camp reflects on pertinent local and global issues from the unique perspective of Fa'afafine by creating an alternate, queer world that is both confronting and hypnotic in its humanity, whilst redrawing the afflictions of colonisation. Through Paradise Camp, Kihara amplifies voices within her own community, returning the gaze in a profound gesture of empowerment while camping the notion of paradise as a form of 'In-drag-enous'.

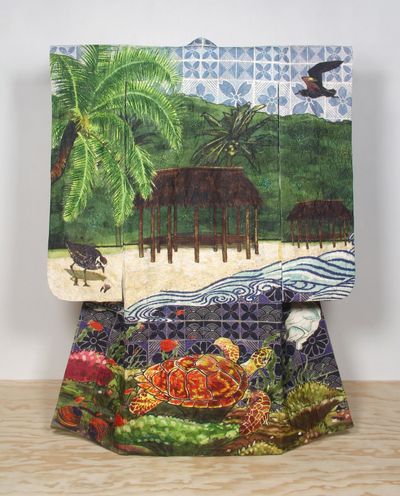

For the 59th Venice Biennale, Paradise Camp is presented at the Artiglierie building in the Arsenale complex against a vast wallpaper of an oceanscape and siapo pattern, the traditional Sāmoan bark cloth made from mulberry tree.

For the past three years, Kihara has been working with curator Natalie King, navigating delays, endless Zoom meetings, and scenario planning in the face of a global pandemic. Despite these challenges, curator and artist have developed a rapport across time zones and waterways to shape the project Paradise Camp alongside two global outreach programmes: Firsts Solidarity Network and Talanoa Forum.

Leading up to the opening of the 59th Venice Biennale, Kihara embarked on a dialogue with Paradise Camp curator Natalie King, discussing early influences, colonial portraiture, research methodologies, and empowering the Fa'afafine community in her new work.

NKYou were born in Sāmoa, went to primary school in Ōsaka (and speak the Ōsaka-ben dialect), and St Patrick's College Silverstream in Wellington before studying fashion at Wellington Polytechnic.

Can you discuss your ancestry and how you became an interdisciplinary artist?

YKMy Sāmoan mother met my Japanese father, who was a JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) volunteer in 1973, on Upolu Island in Sāmoa. Shortly after I was born in Sāmoa in 1975, my parents moved to Jakarta, Indonesia due to my dad's civil engineering contract, and subsequently to Ōsaka, Japan around 1980.

There, I attended kindergarten and primary school before my parents decided to move back to Upolu, to open the first Japanese restaurant on the island called Lesina's Lounge around 1989, which ran for almost 11 years. The restaurant served fusion Sāmoan and Japanese cuisine, catering for the locals. Moving around a lot as a child, I was exposed to diverse cultures and people. My first real job was in hospitality because I was made to work at the restaurant by my parents.

My parents wouldn't let me go to art school, so I ended up training as a fashion designer instead. I remember struggling as a fashion student because the training was geared towards graduates being 'industry ready' to enter a very conservative fashion industry, while I was more interested in using fabric as a sculptural material with fashion shows as a form of performance art.

The theatricality in my work partly came from growing up watching Fa'afafine beauty pageants in Sāmoa, which featured elaborate sets, drag shows, glamorous gowns, and costumes; they created a fantasy world literally from the ground up.

Students in my class were busy looking at Vogue and the bias-cut dresses of Christian Dior and Balenciaga, whereas I was looking at anthropology books, production techniques of Sāmoan siapo, and how Sāmoan migrants were adapting to their new environment in Aotearoa [New Zealand] through various forms of dress.

I could have easily bailed out of fashion school, which was overwhelmingly white, but I stayed and persevered. I told myself that if I can survive this, then I can survive in the real world by creating my own space, on my own terms.

NKHow has your training in fashion informed your constructed, theatrical, and cinematic scenes often shot in distinctive and historically pertinent locations?

YKAfter graduating in 1996, I worked mostly as a freelance costume designer and wardrobe manager for choreographers, theatre directors, and TV and film directors. I also staged fashion shows in raves and worked as a fashion editor for various magazines and newspapers until early 2000.

It was during this period that I was exposed to the creative processes of mise-en-scène to tell my own narratives. This was also a tough period in my life transitioning into living as a 'trans woman' because I didn't necessarily 'pass' as a woman due to my androgynous appearance. It became a barrier to getting jobs outside of the creative industry, so I was periodically on unemployment benefits, sometimes with just five dollars to my name.

The theatricality in my work partly came from growing up watching Fa'afafine beauty pageants in Sāmoa, which featured elaborate sets, drag shows, glamorous gowns, and costumes; they created a fantasy world literally from the ground up.

There were several Fa'afafine beauty pageants in the 1980s and 90s run by various charity-driven organisations, but the pageant that stood out to me is the 'My Girls' production during the 1990s, led by the late Moefa'auо̄ Tanya To'omalātai, a Fa'afafine pioneer who produced, directed, choreographed, and MC'd the pageant.

She was a multitasker who did everything! She was even able to have local politicians and archbishops as judges. I saw Fa'afafine pageantry not just as entertainment, but something that provided visibility for the Fa'afafine community at the time, back when they were used as scapegoats for causing AIDS and natural disasters by religious leaders and the media.

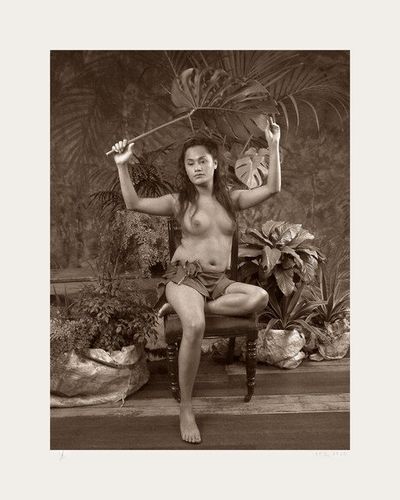

NKIn 2008, you held an acquisitive exhibition Living Photographs, at the prestigious Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, presenting a series of sepia-toned self-portraits 'Fa'afafine: In the Manner of a Woman' (2004–2005), which re-enact late 19th-century postcards of Sāmoan people taken by Western photographers.

Can you discuss your research into colonial studio portraits and gender classifications in this series, where you masquerade and perform a variety of genders and your identification as Fa'afafine?

YKWhen I look at early studio photography of Sāmoan people, Western photographers played multiple roles in how theatre or film productions were made, ranging from writing, producing, and casting to set design.

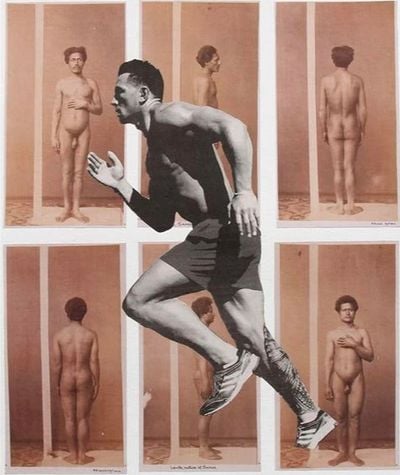

Informed by colonial stereotypes of gender, race, and sexuality, these photographers imposed their own biased views, which would result in the development of the 'dusky maiden' and 'noble savage' trope for commercial consumption by Western audiences to propagate colonial domination in the Pacific.

In Sāmoa we have four genders: Fa'afafine—'in the manner of a woman', which describes those who are assigned male at birth and express their gender in a feminine way; Fa'atama—'in the manner of a man', which describes those who are assigned female at birth who express their gender in a masculine way; Fafine, describing cisgender women; and Tāne, describing cisgender men.

Today, the term Fa'afafine loosely encompasses the Fa'afafine, Fa'atama, and LGBTIQ+ communities. In my Sāmoan passport, I'm recognised as a ʻM'. In my New Zealand passport, however, I'm recognised as a ʻF', which for me stands for Fa'afafine.

NKYou are an avid researcher and voracious reader, as well as a fellow at the National Museum of World Cultures in the Netherlands, with deep research augmenting your staged photograph, as with Epeli Hau'ofa's essay 'Our Sea of Islands' (1993), which was also reprinted in the 2017 Honolulu Biennial (8 March–8 May 2017). How does this essay resonate with you?

YKIn 'Our Sea of Islands', Epeli elaborates on the origin of the division within the Moana:

'Continental men, namely Europeans, on entering the Pacific after crossing huge expanses of ocean, introduced the view of "islands in a far sea". From this perspective the islands are tiny, isolated dots in a vast ocean. Later on, continental men—Europeans and Americans—drew imaginary lines across the sea, making the colonial boundaries that confined ocean peoples to tiny spaces for the first time. Today, these boundaries define the island states and territories of the Pacific.'1

I want to extend Epeli's idea about 'imaginary lines across the sea' to include the imaginary lines of race, gender, and sexuality that privilege whiteness, cisgenderism, and heteronormativity inherited from colonisers and missionaries who have marginalised Moana queer peoples for centuries.

When Sāmoa declared independence in 1962, the Fa'afafine community was left to fend for themselves against legislations formally introduced by the New Zealand administration, including the Crimes Ordinance 1961 act, which targeted the Fa'afafine community to conform towards heteronormativity.

Although the act was abolished in 2013 and it is no longer illegal for Fa'afafine to publicly appear as women, homosexuality remains illegal. Sāmoa, however, has made strides to include the Fa'afafine identity in the Year 10 curriculum, and major corporations in Sāmoa such as Vodafone have welcomed Fa'afafine employees to wear puletasi—a customary dress for Sāmoan women—in the workplace, so it seems that we are making progress, which is great.

The Stonewall Riots of 1969, seven years after Sāmoan independence and credited as the start of the global LGBTIQ+ civil rights movement, have often overshadowed local stories of Indigenous queer peoples in the Moana, while sexual encounters between colonialists and the natives in the Moana have shaped Western notions of gender and sexuality including homosexuality and transgenderism.

There is a misperception in the West that often idealises Moana cultures as a model for how to embrace 'third gender' identities—Fa'afafine are seen as noble savages with a 'primitive' gender and sexuality, living close to 'nature', as measured against the 'civilised' Western heteronormativity.

This is also alluded to in the works of artist Paul Gauguin who deliberately painted androgynous figures or Māhū, which is an identity he was branded with. Māori people made a mockery of Gauguin when he first arrived in Tahiti, seeing him as Māhū due to his long locks of hair.

While Gauguin's work might offer a 'glimpse' into Moana queer culture during his time, it also romanticises the Moana queer experience without acknowledging the colonial experience that has shaped Māhū and other Indigenous gender and sexual minorities.

NKCan you discuss the genesis of the epic and elaborate project Paradise Camp for the 59th Venice Biennale, and the process of working as a director and producer by assembling a cast, crew, and sourcing locations, props, and equipment?

Fortunately, I was able to visit Sāmoa in March 2020 and witness the final phase of the photoshoot at various sites. What are the origins of the title? Can you elaborate on the recce, casting, facilitating partners, and designing costumes to repurpose and upcycle Paul Gauguin's paintings?

YKThe solo exhibition Paradise Camp presented at the Aotearoa New Zealand Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale in the Arsenale consists of a series of photographs, video, and archives that converge to highlight the optics of the Fa'afafine worldview—that there is more than meets the eye.

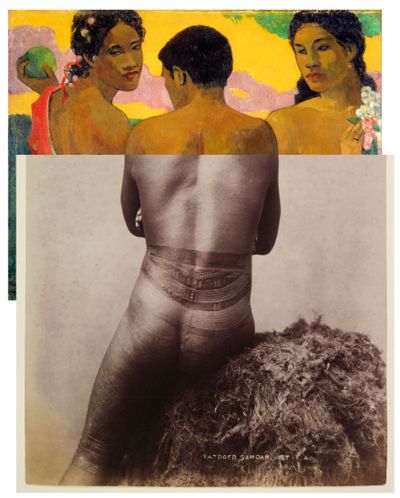

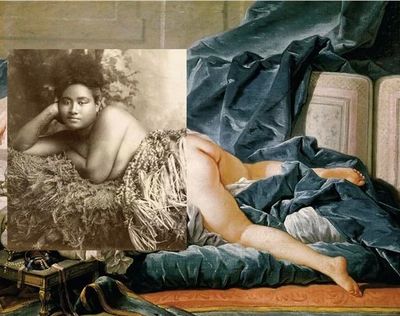

Just as Gauguin used Sāmoa as source material, disguised with Māohi titles, I did the reverse by repurposing his paintings created during his time in French Polynesia between 1891 and 1903.

Paradise Camp is also a provocation against the stereotypical ways we understand place, gender, sexuality, and their intersectionality: it aims to raise questions about how we can decolonise ways of being in the world.

Paradise Camp was created with Fa'afafine and Fa'atama audiences in mind and will tour Sāmoa after the Venice Biennale. The exhibition will be a space for continuous mediation where the Fa'afafine community can reflect on its past while offering a Fa'afafine worldview to those outside the community.

While Gauguin never stepped foot in Sāmoa, I have uncovered archival evidence revealing that he used colonial photographs of people and places in Sāmoa, which resulted in the creation of his major paintings.

Just as Gauguin used Sāmoa as source material, disguised with Māohi titles, I did the reverse by repurposing his paintings created during his time in French Polynesia between 1891 and 1903. Those works severed the exotic impulse of Western audiences by taking back the gaze, repurposing and upcycling his works to a higher quality, as you would in the context of sustainability, whereby old or discarded sources are improved, to convey the Fa'afafine worldview that is often marginalised.

Paradise Camp as a concept was inspired by an unpublished essay titled 'He tangi mo Ha'apuani: Gauguin's models – a Māori perspective' by leading Māori scholar Dr Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, presented to the Gauguin Symposium in September 1992, at Auckland Art Gallery.

Te Awekotuku discusses how Gauguin deliberately painted his models androgynous and exotic as a reflection of his personal and sexual fascination with the Māhū—the equivalent of Fa'afafine within the Indigenous culture of Tahiti, as described in his journal Noa Noa.

Te Awekotuku makes similar observations about the androgyny of the models in Gauguin's paintings who looked like members of her whānau [extended family or community of related families], who were Takatāpui—the equivalent of Fa'afafine in Māori culture in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Following Te Awekotuku's essay, I looked at the Gauguin painting titled Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–1898) online and saw the figure in the middle being a Māhū. Upon further inspection of other figures in the painting and their poses, they strangely reminded me of similar poses in the painting Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1863) by 19th-century French painter Édouard Manet.

It was then that I had the epiphany to look at Gauguin's work with a critical eye to see what other similarities I could find, and sure enough I was able to uncover both direct and indirect links between Gauguin and Sāmoa that have never been seen before.

In a publication titled Gauguin and Maori Art (1995), art historian Bronwen Nicholson describes that in August 1895, Gauguin arrived in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland in Aotearoa New Zealand where he spent ten days en route to Tahiti for the second and final time.

During his brief time in the city, Gauguin visited Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and the Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira, where he recorded and made detailed sketches of Māori and Moana treasures and took a small but vital collection of new images, several of which later appeared in his major paintings.

I suspect that it was in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland that Gauguin picked up several photographs of Sāmoa taken by Aotearoa [New Zealand] colonial photographers, including Thomas Andrew whose photographs were circulated across Aotearoa at the time.

Eight years in the making, the 'Paradise Camp' photographic series and First Impressions: Paul Gauguin (2018), an episodic talk show, were both produced in Sāmoa, and involved the combined cast and crew, many of whom had never stepped foot on a film set before, gaining employment and new skills along the way.

Even though the cast may not have known who Gauguin was, there was a collective enthusiasm towards a major production of this scale, initiated by myself as part of the Fa'afafine community. Sāmoan cultural values were at the centre of our creative production.

For example, within the team, I invited Fa'afafine and Fa'atama elders as advisors to the project to ensure cultural safety. At the end of the photoshoot, the cast and crew assembled to offer speeches of gratitude and we sang a hymn to mark the end of our production.

NKParadise Camp comprises 12 new, luscious photographs with 11 shot on location in Upolu with members of your community in March 2020. Cindy of Samoa, a renowned performer and singer, appears in Spirit of the ancestors watching (After Gauguin) (2020) reclining seductively before a beach scene, under a palm tree.

You have replaced the spirit with the ocean, further enhanced by setting your photographs against a vast wallpaper of Saleapaga Beach, which was decimated during the 2009 tsunami. How has the ocean become emblematic of environmental crisis and small island ecologies for you?

YKThroughout history, small islands in the Moana Pacific have always been associated with the ocean as an intrinsic part of the island's identity. However, the way the Moana ocean is viewed, including its ecology is predominantly heteronormative.

In the book Evolution's Rainbow (2004), evolutionary biologist Joan Roughgarden argues that Charles Darwin's theory of evolution prioritises heterosexuality as solely responsible for the survival of species, including humankind, despite a plethora of examples in the animal kingdom that challenge this notion.

A prime example of this is the selection of coral reef fish residing in the ocean surrounding the Sāmoan archipelago that change sex, including reproductive function, and practice sex-role reversal, allowing their kinship system to become resilient species for centuries.

These include tu'u'u-lumane, or pink skunk clownfish, which are protandrous hermaphrodites—meaning they are assigned male at birth but can change sex; the mano'o, or broad-barred goby, which, when paired with the same sex can change to the opposite sex when they colonise a new coral patch; the sugale, or bluehead wrasse, for which female sugale can change sex later in life and become male; and the pusi, or moray eels, which are assigned as hermaphrodite at birth.

There are over 900 fish species in Sāmoa, many of which are being threatened by global warming. As the survival of the planet relies on the biodiversity of all underwater species, the plight of non-heteronormative underwater species serves as an allegory to the Fa'afafine experience.

NKCan you also discuss your climate change workshops with the Sāmoa Fa'afafine Association?

YKParadise Camp explores how Fa'afafine, Fa'atama, and LGBTIQ+ communities address a variety of issues including climate change in Sāmoa. A recent scientific report jointly released by the Australian and Sāmoan governments describes Sāmoa as being at the frontline of climate change, with frequent cyclones, rising sea levels, and extreme weather patterns inflicting extensive damage on the islands, which is a trend projected to continue.

As an extension of Paradise Camp, I assisted a workshop led by the Pacific Climate Change Centre and the Sāmoa Fa'afafine Association held on 29 October 2021 with an aim to empower the Fa'afafine community with knowledge and understanding about climate change to build resilience and become a better-informed community.

NKCindy also sings on the newly commissioned soundtrack to Paradise Camp. How important has it been to involve your community and create a Fa'afafine utopia or Paradise Camp universe?

YKParadise Camp is an exhibition that prioritises the Fa'afafine community as its primary audience. And for the Fa'afafine community to feel that Paradise Camp is theirs and that they are being represented in the exhibition, we have involved them from the beginning with a series of consultations in addition to including them in the production of the work, both behind and in front of the camera.

I wanted to counter many photographs of Fa'afafine in the public domain that are mostly captured by white documentary photographers, which are voyeuristic and do not empower the Fa'afafine community but degrade them. I am thrilled that Paradise Camp will tour Sāmoa in 2023.

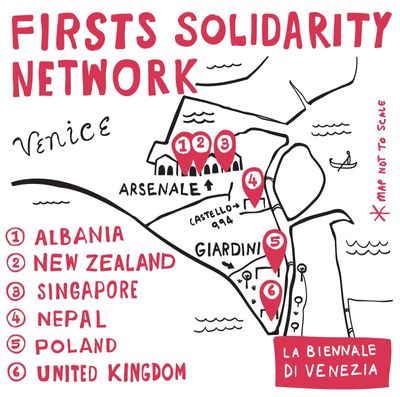

NKYou are the first Pasifika, Asian, and Fa'afafine artist to represent New Zealand at the Venice Biennale, which you have referred to as a moment of 'turning the page'. How is the experience of being a 'first' leading to the Firsts Solidarity Network?

YKFor me, being acknowledged as the first artist representing New Zealand at the Venice Biennale who is Pasifika, Asian, and Fa'afafine comes with a responsibility to ensure that I keep the doors open for other marginalised communities to come through. In addition, presenting at the Venice Biennale in the Covid-19 environment comes with many challenges.

With that in mind, I've formed the Firsts Solidarity Network group—an artist-led initiative of artists who are first-time representatives from marginalised or under-represented groups in their respective countries, or a first-time participating country in the Biennale, to offer Venice visitors a route to discover these 'firsts' at the global art world event.

For artists and curators, the network offers practical advice and camaraderie among participating pavilions. In addition, I hope the Firsts Solidarity Network encourages discourse around pertinent issues such as the internal structures of national pavilions and their commitment towards the equitable representation of artists in their respective countries.

NKWe live in times of global violence, political tension, communal disparity, and ecological mayhem. Paradise Camp addresses urgent issues of environmental crisis, small island ecologies, and intersectionality. How have you woven these concerns into your new work by focusing on the local and global?

YKI am particularly interested in exploring the intertwining of divinity, earth, and climate change in the photograph Genesis 9:16 (After Gauguin) (2020). The title of my exhibition is intended to 'camp' the notion of 'paradise'. Paradise Camp adds the Indigenous in drag, which I call 'In-drag-enous'.

The Pacific region has become synonymous with images of unpolluted and vacant white sandy beaches that are constantly recreated by the tourism industry. They are also commonly featured on screensavers of millions of people around the world, becoming ironic and cliché in popular culture.

However, those clichéd images of white sandy beaches are real places in Sāmoa with real people who've lived there for generations, faced with real-life issues such as climate change—given that almost 80 percent of Sāmoa's population live along the coastal areas.

Scientific data shows that the global average for sea-level rise is 2.8 to 3.5 millimetres a year, compared to Sāmoa's sea-level rise measuring up to 4 millimetres a year.

Fa'afafine are often known to be first responders to natural disasters, particularly during the devastating tsunami in the Aleipata district in 2009, where Fa'afafine were pulling bodies out of the rubble and assisting families with young children to settle into the emergency shelter. However, many Fa'afafine refrained from using the bathrooms at the shelter because they weren't gender neutral.

This is just one of many untold stories from the Fa'afafine community that are often ignored in the development of national disaster management planning.

In response to this dilemma, I've been working closely with the Sāmoa Fa'afafine Association to host a series of climate change workshops targeting the Fa'afafine community, so we can address these issues by developing solutions that can be implemented nationwide.

This is partly the reason why I created the work entitled Genesis 9:16 (After Gauguin). In the Bible, 'Genesis 9:16' describes the rainbow as a symbol of the sacred covenant between the divine and all living things on earth. Although I am not a practising Christian, I believe this covenant is pertinent for Sāmoans living on an archipelago at the frontline of climate change, where sustainability is an issue.

Fonofono o le nuanua: Patches of the rainbow (2020) features members of the Aleipata Fa'afafine Association dressed in rainbow-coloured costumes, and repurposes and upcycles the composition of the painting Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? by Gauguin.

The title of my work, however, is lifted from a poem by Sāmoa-based poet Reverend Ruperake Petaia, which alludes to the Sāmoan concept of Vā fealoaʻi, which means to nurture the space between things, a space that connects and mediates relationships between people and between people and nature.

The poem 'Fonofono o le nuanua' (Patches of the rainbow, 1951) addresses Gauguin's questions indirectly, especially in the context of sustainability. Even though others might see the rainbow as a reference to the Gay Pride movement, my intention is to highlight the syncretic spirituality in Sāmoa, which fuses a Sāmoan Indigenous worldview with Christianity.

NKIn the Sāmoan context, the rainbow symbolises a portal into the spiritual world. In the final image of the 'Paradise Camp' series, you return to the studio and cast yourself as a Gauguin self-portrait in an ingenious reversal and transformation with prosthetics.

This seems like the penultimate decolonial gesture of masking, disguise, and parallel acts of creation. What gave you this idea for Paul Gauguin with a hat (After Gauguin) (2020), and how did you feel?

YKMy idea was to subvert the art historical canon dominated by artists who are dead white men. On a much more personal level, I often think that the left side of my face appears more masculine than the right side, so I wanted to confront and overcome my insecurities about not 'passing' enough as a woman in public.

The more I disguised myself, the further it revealed my thoughts about colonially constructed boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, and geography.

Making this work, I felt nervous, excited, and exhausted at the same time. It made me think about mortality and the legacy one leaves behind while I was bringing Gauguin back from the dead.

The more I disguised myself, the further it revealed my thoughts about colonially constructed boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, and geography. RuPaul once said that drag doesn't hide but rather it reveals who you are.

NKWe are planning a Talanoa Forum in October called 'Swimming Against the Tides', which is a phrase derived from Māori filmmaker, Merata Mita. How important is it for you to have outreach programmes as part of your presentation at the Venice Biennale?

YKI've put together the Talanoa Forum to further the conversation about intersectionality between identity politics, decolonisation, and climate change, which are themes that are also explored in Paradise Camp. I also wanted to find a way to bring grassroots community leaders, activists, artists, scholars, and policy makers who may not have heard of each other but are all interested in the same ideas and synergies that might come out of that talanoa.

Talanoa is a pan-Polynesian word used to describe a process of inclusive, participatory, and transparent dialogue. Using talanoa as a point of conceptual departure, the theme of the Talanoa Forum, ʻSwiming against the tides', is lifted from a quote by the late Māori New Zealand filmmaker Merata Mita, whose work explored the political tensions in Aotearoa New Zealand during the 1970s and 80s, which brought issues such as Indigenous sovereignty and gender equality to the fore.

Mita's words orient the talanoa to explore how localised strategies including art, activism, and policy are being developed to address global concerns of our times. —[O]

A version of this conversation can be found in Yuki Kihara: Paradise Camp, edited by Natalie King, published by Thames & Hudson, April 2022.

1 Epeli Hau'ofa, 'Our Sea of Islands', A New Oceania: Rediscovering Our Sea of Islands (1993): p.2–17.