Stephanie Syjuco on Rendering the Nation

Stephanie Syjuco. Courtesy the artist.

Stephanie Syjuco. Courtesy the artist.

For Stephanie Syjuco, the politics of an image lies in its rendering. Whether in a studio, via computer effects, or through the gesture of an artist's framing.

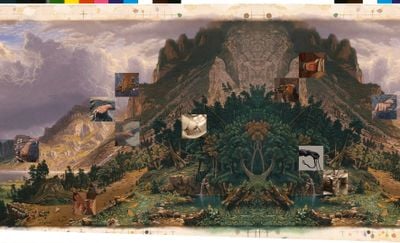

This politics is brought into focus in Syjuco's site-specific installation at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Double Vision (15 January–December 2022), which takes up the 50-foot-wide and 15-foot-tall walls that form the entrance to the institution's 19th-century collection of American art.

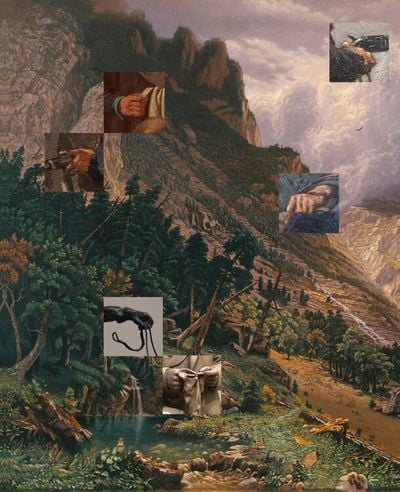

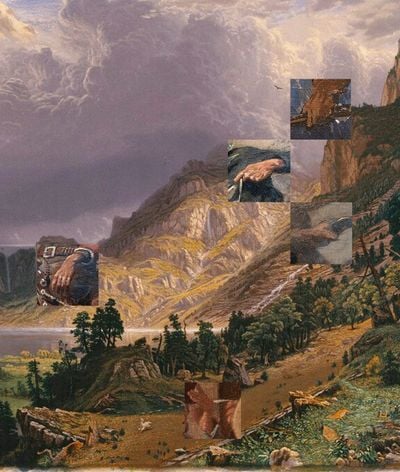

Critically engaging with the mythologies surrounding the American West expressed in the museum's collection, Syjuco has digitally altered landscapes by Albert Bierstadt and printed them on vinyl wall panels andfabrics. One landscape, printed with mirrored sections of Bierstadt's chromolithograph print The Storm in the Rocky Mountains (ca. 1868), is dotted with square images of hands photographed from paintings in the museum.

Bierstadt's The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Peak (1869) was printed on green panels for the second mural, which acts as the mount for studio photographs of bronze sculptures by Frederic Remington with the tools of their capture—colour correction cards, identification tags, measuring devices, even a museum worker's hand—in full view. The exposure of studio techniques is central to Syjuco's practice, which explores the construction of images—and in turn, identity—through a critique of historical representation.

Taking centre stage in The Visible Invisible, the artist's recent solo exhibition at the Blaffer Art Museum (17 October 2020–10 January 2021), were large room-scale 'still life' installations arranged on platforms.

Neutral Calibration Studies (Ornament + Crime) (2016) is a striking amalgam of objects and images, including an image of a Swedish Playboy model used to engineer the JPEG and a picture of Black Panther Huey P. Newton in a traditional Filipino rattan chair.

Likewise, Dodge and Burn (Visible Storage) (2019) brings together images referencing America's colonialist expansion in the Philippines with those of contemporary racial politics. Amid enlarged stock photos of tropical fruits, printouts of Philippine antiquities from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's online database, and a photograph of Japanese American women in a WWII internment camp, is an enlarged inverted colour calibration chart.

As with the installation's title, which refers to Photoshop functions for lightening or darkening images, the colour chart's presence, used to ensure monitors are displaying colour correctly, extends Syjuco's reading of empire's colour-coded narrative.

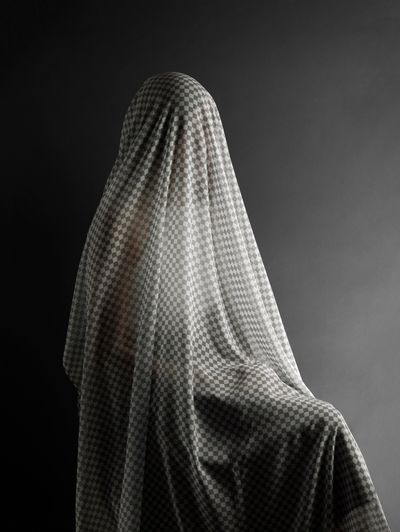

Syjuco hand-stitched the 19th-century colonial-era American dress and traditional 19th-century Filipinx 'terno' dress worn by the mannequins constructed from the same fabrics used for the backdrop of AV production. The former with green screen fabric used to create visual effects in film post-production, and the latter with the grey-and-white chequered pattern indicating a transparent layer in Photoshop.

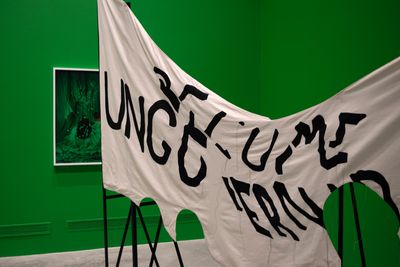

Both materials appear throughout Syjuco's work, including the 'Chromakey Aftermath' series (2017): monochromatic photographic studio compositions presenting props of protest constructed from green fabric.

In Chromakey Aftermath (Standard Bearers) (2019), two people in a green room cloaked in green fabric sit with their backs to the camera, each wielding a green flag. The image was among Syjuco's works shown on rotation in Low Visibility at Walker Art Center (5 February–21 November 2021), a group show confronting an era of surveillance with artists like Hito Steyerl and Walid Raad.

Also shown was the archival pigment print Total Transparency Filter (Portrait of N) (2017). A college-educated 'Dreamer'—an individual protected by DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), an immigration policy repeatedly threatened under the Trump administration—sits shrouded in sheer fabric printed in grey-and-white check.

Total Transparency Filter (Portrait of N) was first exhibited in CITIZENS, a 2017 solo at RYAN LEE Gallery, where Syjuco will open a solo exhibition on 6 January 2021, alongside a black curtain printed with 'I AM AN AMERICAN'. The statement references the sign a Japanese shopkeeper hung outside his Oakland store before forcible internment in the U.S. after the bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

Stories like these drive Syjuco's conflation of rendering and representation with the nature of national identity as a construction. A mix of reality and fiction that Syjuco pointed to in Rogue States, an installation of 22 flags hung from the ceiling of the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis in 2019, the majority based on those seen in Hollywood movies like Die Hard 2 (1990), to represent fictional, non-Western enemy states.

What is often omitted in such narratives are the colonial entanglements that define the United States, which drives the references to the Philippines in Syjuco's work more than her Philippine heritage.

In this conversation, Syjuco walks us through her latest installation, and reflects on how her practice has evolved in recent years to focus on the lived implications of nationalism in America.

SBFor your installation at the Amon Carter, you engaged with the museum's collection to create two digitally altered landscapes. That must have been an interesting space to enter, given the museum's collection and the invitation to reflect on it critically.

SSI was very excited to do a project in Texas at the museum, because unlike an invitation from the Smithsonian or a larger national museum, the Amon Carter is regional and has quite a specific focus in its collection. It is a museum of American art from a Texas perspective.

Then, there was the fact that they invited an Asian-American artist based in the West Coast to come and respond to their collection.

The Carter is so an interesting because it is in many ways a direct reflection of the original donor who started the museum with their selection of American paintings and sculptures focusing on notions of the American West.

Many of the works express ideas of moving westward, expansionism, and manifest destiny from the perspective of settlers and European migrants. It's founding core collection is very 'cowboys and Indians'.

I was invited by the museum's photo curator Kristen Gaylord to see what resonated with me from the collection. We originally thought I could respond to issues of immigration or colonialism in similar ways that I've worked with the Smithsonian's collection in the past, which is to mine their national archives and photographs.

As an artist, part of the challenge of working on new commissions is also about understanding the limits of an institution.

When I got to the Carter, I became fascinated by their construction of American history by using artworks that romanticise the West, particularly paintings and sculptures by Frederic Remington and Albert Bierstadt. I chose them because of their pivotal position in American art history and how their works have become almost ubiquitous in the dominant visual narrative of 'the West'.

SBCould you walk us through the installation?

SSThe installation will be on display for one year in the main entryway that connects two of the major museum wings. It's the passage you first walk through to get to the main historical collection. For me, the project is an entry point to start a conversation that could tweak the way a visitor would see the rest of the museum.

There are two walls that face each other, each covered with large-scale digital wall vinyl murals of altered landscapes, to form a type of 'backdrop' for sets of photographs placed on top of them.

One wall reproduces a landscape in a chroma key green hue, and the other is a full-colour landscape with image panels of men's hands excerpted from paintings within the Carter's American West collection. The whole project is meant to reframe existing artworks in the Amon Carter through the critical lens of staging and construction.

The landscapes included as the backdrop in each mural are by Alfred Bierstadt, a German immigrant whose landscape paintings influenced the way the rest of the United States viewed the West.

One thing I struggled with was how to utilise and work with images from the museum collection that depicted Native Americans. I needed to figure out how to critically reframe their depictions, and differently from how Bierstadt did, which was as part of an idyllic, stylised landscape, like non-actors in the construction of the country.

Rather than erasing or removing their presence, I decided to heavily pixelate the original images so that the figures are difficult to identify, like what you'd see in contemporary anti-surveillance images—a kind of deflection of the gaze.

I wanted to frustrate the ability for an audience to consume the images as they were originally shown because the way these people were depicted was inaccurate and heavily constructed from a settler perspective.

SBThat idea of deflection recalls the 'Applicant Photos (Migrants)' series (2013–2017): passport-style black and white images in which heads are covered in patterned fabrics.

While one could construe these to be tribal patterns, they also look like the razzle-dazzle camouflage on World War II war ships. It's a kind of warding off through confusion; like anti-facial recognition technology.

SSIt's also a lot like an earlier work I made this year, Headshots (Witnesses) (2021), which heavily pixelates faces of Filipinos on display at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. It was a different way of shielding, without the hands.

By using contemporary digital pixellation, I wanted to bring forward a contemporary criticality, and not relegate these images to an ethnographic, white historical gaze.

History museums in particular tend to frame things as being resolutely in the past, which suggests that we have either learned from it, or we have moved beyond it. I wanted to introduce a level of contemporary obfuscation to bring these problematic histories of vision and depiction into the present.

SBThe idea of bringing history into the present comes through in the mural where you have a landscape printed on chroma key fabric.

That green-screen colour speaks to this act of rendering, which is amplified in the augmented landscape covered in men's hands that extends the metaphor. You've turned classic landscapes into a Photoshop interface.

SSYes, the 'man hands' come directly from the historical painting and sculpture collection on display, which falls directly into the timeframe of an overt Manifest Destiny in the United States. I walked through the galleries with my camera focusing on the hands specifically as a kind of metaphor for manipulation and action.

There's a mix of hands performing different actions, like holding onto reins or grabbing things; pulling, pointing, or signing. It's also not lost on me that these are men's hands in the paintings, and the men are the focus of how the land and peoples are 'tamed'.

I was also thinking about not only the physical aspects of this taming of the West through brute force or overwhelming strength, but also governmental and institutional legislation. Documents, contracts, and laws determine who this land belongs to, which nullifies the rights of indigenous peoples inhabiting it.

SBThe images framed by the green mural are of bronze sculptures by Remington, which you staged and photographed, right?

SSThere are four large-scale photographs of bronze Remington sculptures that feature hands coming into the frame, and these were carefully arranged and 'stage managed' to get the final images.

For me they are a way to challenge the iconography of the cowboy as a heroic figure that tamed the West, which is full of so many romantic notions, not just in Texas but across the United States.

SBWhich is so problematic, isn't it? I once reviewed a show pinned to the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), a classic Western, and the basic premise was the question of whether America was built by the criminal or the lawmaker.

It seems a paradox or a self-fulfilling prophecy that the cowboy, who represents this rebellious lone wolf, becomes the embodiment of the nation, which presupposes this idea of rebelling against the state, the law, or acting in a way that does not conform to it.

SSThat sounds about right!

SBWith that in mind, I look at your pictures of the hands grasping Remington's sculptures, and it makes me think about colonial theft.

SSWell maybe in a reverse sense, because all the hands coming in belong to museum staff. The one with the green gloves is a professional museum preparator's.

I was using the tools and apparatus of the museum, as well as working with the staff, to pose with these objects, because I wanted to show the very human stage management and care that happens in the construction of the story of the American West.

When you to go into the museum's vaults and see the artworks and how they're stored, protected, and cared for, I see that care as a metaphor for the stewardship of the narrative of the founding of America.

The 'story' as told through these artworks and exhibition displays is completely cared for and managed. And that storyline is problematic as well as potentially promising if critically examined and challenged.

SBI love how you extend the past into the present through idea of tactility and ambiguous acts of care. Could talk about how you worked with staff and how they felt about being involved in the stagings you set up? It feels like you were workshopping with the museum itself.

SSI feel really lucky because it takes a certain kind of curator to work with an artist to produce a new body of work based on a museum's existing collection. It's different from just pulling in or curating an existing artwork.

You have to be flexible and able to negotiate together. Working with the staff and curator at the Amon Carter was really wonderful and I felt really supported in trying out ideas and brainstorming possibilities.

They were really open, and I feel honoured to have been invited to do so. We could have chosen several different pathways and themes for the exhibition, and it was an exciting and productive way to work.

As an artist, part of the challenge of working on new commissions is also about understanding the limits of an institution. The Amon Carter is aware of how its initial collection reflects its founder's perspective, but is open to critical engagement with it. I don't think they would have invited me to work with them if they weren't open.

In contrast, I have experience working with other museums and organisations for whom compromise or rapid conceptual pivoting had to take place for things to move forward. There are indeed many hands needed to make a new body of work about—and within—an institution, and they are all important in the process.

SBThat makes me think about Langston Hughes's poem 'Freedom's Plow', in which he talks about all the hands that made America.

By bringing the staff into the frame, you bring up their assumed role as instruments of an institution: individuals who often get pulled into a macro-critique of nationalism or state power that they may or may not align with.

SSYes, they also have to wrestle with the legacy of what they were given. The things we inherit are still things we can choose to engage with or accept. I like to be optimistic in thinking that even an institution devoted to a very particular story has the capacity and willingness to shift perspective.

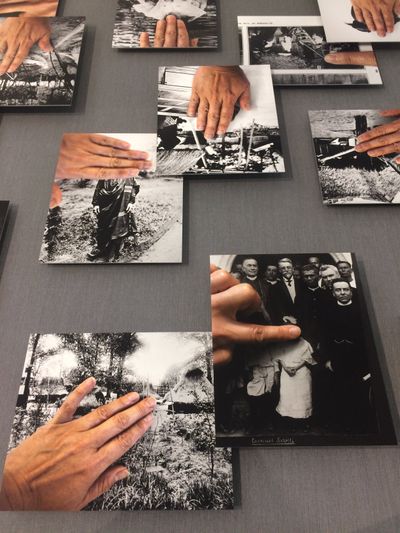

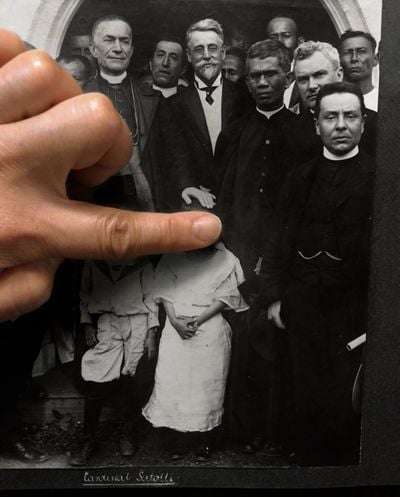

SBWith that in mind, the presence of hands in this installation connects with the images you created for Block Out the Sun (2021). For this project, you spent time in the archives of the Missouri Historical Society and the St. Louis Public Library ahead of your exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis.

You photographed archival images of the notorious Philippine Exhibit at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, which presented a human exhibit of over 1,000 Filipinos from at least ten different ethnic groups from the Philippines, with your hand covering each figure.

SSThat's a really good connection, because to work on-site, whether it is with the archives at the Smithsonian or at the Amon Carter, you're confronted with historical images that are unchangeable.

You literally cannot remove anything from the archive no matter how problematic it is, because the whole point of it is to provide a record, a stewardship of knowledge at that time, and from that particular perspective.

Given the fact that these archival ethnographic photographs are unmovable, how can you speak back? I was really struggling with what's possible, and the only thing I could think of was something quite personal, which was touching the photos, which is really kind of bad.

The work was at once a protective gesture, an attempt to connect a hundred years later. By physically blocking the gaze with my hands, which is a pretty blunt instrument. I am blocking the consumption of images of Filipinx being posed in ways meant to be 'instructive' to the white American audience.

Their display really was less about educating the public and more about constructing a mythology of progress and evolution, with the photo's brown subjects obviously inhabiting the lower end of that spectrum, and the colonial American forces on the higher end.

SBIt's interesting you say it's bad to touch the photographs. It reminded me of Renzo Martens' film White Cube (2020), when Matthieu Kassiama visited New York for an exhibition at the SculptureCenter.

While on a tour of the Met, he came across artefacts stolen from the Congo, and he began speaking to them and gesturing towards touching them. While he knew he couldn't touch these objects, he was also claiming his right to touch them.

SSIn my case, the photographs I was touching weren't considered important enough to wrap up since they were copies of the originals. They were just all there in the file folders, so I just kind of did it.

Then again, I've been thinking a lot about the claim to ownership of images and their appropriation, which speaks to the gesture of directly touching the photographs.

In terms of my Amon Carter show, I would say 80 to 90 percent of what I've produced is a form of critical appropriation and repositioning. There are a couple interventions that include my hands or other people's hands, but ultimately, I'm excerpting and layering. I'm trying to use what is there to re-represent an institutionalised story of America and show how vastly constructed it's been.

I like to be optimistic in thinking that even an institution devoted to a very particular story has the capacity and willingness to shift perspective.

The framing of this story is supposed to be viewed in one way, but if you spin it, you can look at it through the lens of those who did not create the narrative. Then you get a completely different story, which is less about heroism and triumphant expansion, but of the stage managing and construction of empire.

That fascinates me so much as an immigrant American, because to a certain extent, I love the scripted promise of America. But like everyone else, I also inherit its failings and I'm constantly amazed at how excluded I am from its discourse and idea of itself.

SBBy entering the museum's collection and unfolding it, you also insert yourself into the constructions they represent, including the story of America, as you say.

SSThe story of America has always interested me because it's one of self-invention, and I don't mean that in a positive way. I mean the entire narrative is constructed in a very exclusionary way as to who founded the country, who makes up the country, and who's an ideal citizen.

I'm from California, which is where I grew up, though I'm originally from the Philippines and my family migrated here. I went through the whole naturalisation and citizenship process to become a U.S. citizen.

Interestingly, there's also a long history between the Philippines and the United States in terms of empire, colonialism, and economics, so these two countries have been linked for much longer than most people realise.

This history is such an unknown part of the American imagination, it's been completely forgotten. I look at this wilful forgetfulness as an extension of American manifest destiny.

Beyond westward expansion, the United States subscribed to the notion that it could keep expanding overseas, which then fed into its foray with Philippine colonialism and becoming an American empire. It was like, 'We can do this, we did this already with North America, and it makes perfect sense.'

I also know historically there was a lot of pushback, so it wasn't necessarily a done deal in terms of American politics to expand globally, but it was the logic of manifest destiny that justified U.S. expansion into Hawaii, the Philippines, Cuba, and the many other places we euphemistically called and still call 'territories' or 'protectorates'.

These events of early American Manifest Destiny and then overseas expansion are linked, but what's interesting is that in the American imagination, they are seen as very separate moments.

The framing of this story is supposed to be viewed in one way, but if you spin it, you can look at it through the lens of those who did not create the narrative.

At the Amon Carter, I think a big question in the back of some people's minds must be, 'how do all these cowboy paintings and sculptures relate to a female Asian-American artist who hails from the Philippines?' And my answer is that, in many ways, it's a direct line and legacy as to why I am here as a colonial descendent. I really want to challenge the siloing of concerns and foreground the history of U.S. imperialism.

SBWhat comes to mind is A. Sivanandan's famous response to racism in Britain: 'We're here because you were there.'

SSI think that's the point of Manifest Destiny. Manifest Destiny never denied it was doing what it was doing. In my understanding, it was conceived almost as a divine right.

SBBringing back these histories of U.S. imperialism returns to the point you made about how you are an American citizen and a part of you believes in that promise. And yet that question of citizenship—who is an American—is so contested.

It goes back to that Langston Hughes poem, if all these hands made America, then why can't all these hands be it?

SSI think that's a beautiful thing to pull in, because to tell you the truth, I'm not sure how much the average viewer thinks about that idea, of what America is and what it can be, and it would be nice to keep putting in this notion of possibility, and not just indictment in those discussions.

It's really difficult to encourage people to feel like there's still a way out of where the country finds itself now.

Of course, these ideas of nationhood are really complicated, and people have really different perspectives about history and how we should move forward. That's why I'm curious about the reception, or rather its multiple perceptions, of my work at the Amon Carter.

Texas has recently enacted some of the most restrictive anti-abortion laws in the country, as well as laws governing how history and race is taught in its schools. The title of one of my works—a landscape mural covered in hands—is called Manhandled, which relates it directly to a patriarchal system that was set up along with white supremacy.

I'm curious how different viewers are going to think about the work or even how people will phrase or not phrase certain things. I think the exhibition title Double Vision is really apt, as it hints at both complexity and also the potential for obfuscation or shifting perspective.

SBThat relates to the way speech is policed and controlled and the assumptions often made in liberal democracies that restrictions on speech only happen elsewhere.

SSI hadn't thought about that in the larger global context, but it makes perfect sense because if you're not a part of an originating power structure—which here in the U.S. is essentially white supremacy and patriarchy—you will get further if you use metaphor.

Given the fact that these archival ethnographic photographs are unmovable, how can you speak back?

But I would also say that this way of speaking around a subject has been the case for artists of colour in the United States for a very long time, especially if you want to get into places that have traditionally excluded you. You have to be a little shady in terms of how you position things.

That said, I have noticed in the last five years in the United States, as an artist and academic, there is more freedom now to use terms like white supremacy outright. That's actually really new. Ten years ago, you wouldn't be able to say that phrase so openly, like somehow it didn't exist.

SBI suppose this also feeds into your curiosity about how your work will be received in Texas, given the legacy of that state and the work you do around white supremacy?

SSIt's fascinating, right? I hope we won't have to use euphemisms when discussing this work and that it can be visually critical on multiple levels.

SBBut does that also create a discursive framework around the project, in that it becomes open to interpretation?

SSHopefully, which is interesting too. I wonder what it will be like for those who aren't familiar with the rest of my work or previous projects, if those hidden things that could inform a reading of this installation—like a knowledge of how I use sampling or obfuscation in my work—might come through.

SBI wonder if you could answer that. Where would you place this project in the trajectory of your practice and what has it revealed to you?

SSIt's a good question. About four years ago, after the previous presidential election in the United States, I really pivoted my work. Prior to that I was dealing a lot with general issues of culture and globalisation, really broad notions of East and West.

Then, it shifted. I realised that I had neglected to interrogate my own spaces, my own realities of—say being an American and what it means to be an American at this very point in time—and the ways I had been indoctrinated by certain institutional narratives.

I'm implicated in the construction of these narratives as much as they have shaped me, and though I can attempt to critique them I have also, to a certain extent, normalised their power structures.

I think my Amon Carter show ties directly with a previous project called The Visible Invisible, which I did in 2018. I made a set of green chroma key dresses in the style of historical American garments using the same fabric used for backdrops in AV production.

I learned 19th-century sewing techniques to hand sew these dresses and went through the whole complicated process of making these garments from scratch because I wanted to be implicated in the literal construction of this American iconography.

It all relates to this focus I have on looking at the construction of the United States and the construction of America's identity of itself, which includes its colonial histories that are so often ignored.

SBIn Dodge and Burn that really comes through, because you have those dresses staged in a studio set, with the grey and white chequered Adobe filter backdrop and chromakey fabric, which circles back to the Carter installation as a rendering of a country.

SSExactly. It's about manipulation—whether of the image or the people, which is what produces a history or a story. But unfortunately, I think that in the United States, there's a very limited space for how artists of colour are allowed to make work with these concerns in mind.

SBLike the classic problem that artists who are non-white aren't able to speak to the universal.

SSExactly. A lot of people expect me to make work about my Filipino identity. But what is interesting is that with projects like Block Out The Sun and the work I've done at the Smithsonian, where I specifically hunted for evidence of Filipinos and Filipino Americans in the archive, audiences in the United States assume that the work represents a search for my heritage or identity

But it is absolutely not about that. It's actually about how the empire views its colony through its archive. And that's a totally different from wanting to excavate anything about my personal heritage.

SBKeeping it to a narrative of your heritage denies the broader story of America that you are confronting. On that note, you have an exhibition at RYAN LEE Gallery, and also mentioned you were participating in an exhibition at the Singapore Art Museum. Could you introduce what you will be showing and how they extend the themes in your work?

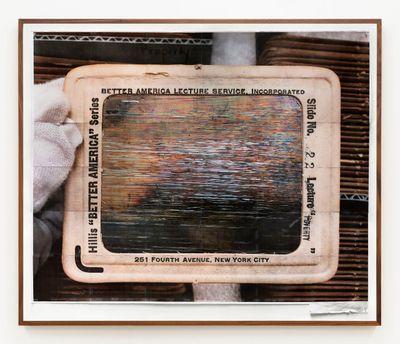

SSMy solo show Latent Images opened at RYAN LEE Gallery in New York earlier this month and features photos and an installation developed over the course of two years. Both the Amon Carter and RYAN LEE shows deal with museum collections, but quite differently.

For Latent Images, I photographed and reprinted documents and images in the archives of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and am presenting them as large-scale blow-ups that show a fragmented and incomplete story.

In some cases, I print my images as crappy laserjet prints, then tape and tile them together before rephotographing them again at high resolution. So there's this shift in resolution from down to up, up to down, and then back again, in order to point towards how the meaning of an archive is also told, retold, mediated, embellished, and interpreted.

And then in the centre of the gallery is a large platform-based work with loose prints arranged on them like a working table of sorts—a visual display akin to an index of an archive.

I'm also 'bleeding' into the archive as well, and you can see in my prints that my shadow is overlapping some of the documents I'm shooting, and you can see my hand poking around like an interrogator. It reminds me a bit of a forensic activity.

What I've learned from working on both shows is I really love diving deep into institutional collections, rummaging around, and pulling forward alternative readings. It's all so rich and waiting for a re-telling! It feels endless.

In Singapore, I'm in conversation with the Singapore Art Museum to participate in a larger exhibition on Southeast Asia photography that is both historical and contemporary.

I really appreciate that as an artist of the Filipinx diaspora, there can be an extension of inclusion in terms of who constitutes Southeast Asia—that because of migration complexities and opportunities, many folks reside outside of its regional boundaries but still have ties that can be traced and connected: the global and the local collapsed by economic and cultural reality. —[O]