Cosmin Costinas: A Walk Through the Kathmandu Triennale

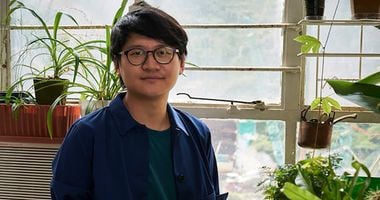

Cosmin Costinas. Courtesy Kathmandu Triennale.

Cosmin Costinas. Courtesy Kathmandu Triennale.

Cosmin Costinas, artistic director of the 4th Kathmandu Triennale 2077 (11 February–31 March 2022), introduces the entanglements and juxtapositions of cultural lexicons and aesthetic sensibilities across the exhibition in Nepal, conceived with co-curators Sheelasha Rajbhandari and Hit Man Gurung.

With a curatorial and writing practice centred on transnational exchanges and ways of conceiving of visual languages beyond borders, Costinas brought a blend of experience to this multifaceted edition of the Kathmandu Triennale, with works by over 100 artists from 40 countries, including Pacita Abad, Lam Tung Pang, Mohamed Bourouissa, and Ashmina Ranjit.

Held across five locations, including a UNESCO world heritage site and Nepal's first modern building, the Triennale discarded the Gregorian calendar date for its Nepali Vikram Samvat alternative in its title, 2077.

Running the Hong Kong-based gallery and non-profit Para Site since 2011, Costinas has long supported artistic practices that counter Eurocentric paradigms in his work, developing Para Site into a key supporter of arts practices in Asia, which was part of the organisation's mandate since its inception. Beyond a gallery space, Para Site offers grants, support, and fellowship programmes, including the yearly intensive workshop for emerging arts practitioners, 2046 Fermentation + Fellowships, and the NoExit Grant for Unpaid Artistic Labour.

While casting an eye on Southeast Asia, it is at the intersection of the global and the local that Costinas' work is located, with an interest in the region stemming from its capacity to reflect 'a kernel of the universal' and embody a myriad of perspectives. 'It is a question of responsibility, and even duty, to reflect the world in its complexity,' Costinas has said.

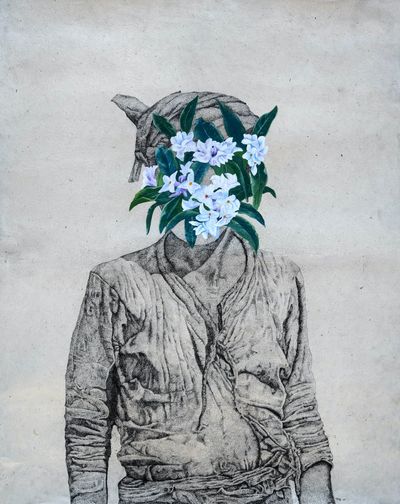

This focus on how objects and ideas connect to a 'broader cosmology' comes through in projects like the travelling show A beast, a god, and a line (2018–2020), which Costinas conceived for the Dhaka Art Summit (2–10 February 2018), before it was adapted for audiences in Hong Kong, Yangon, Warsaw, Trondheim (Norway), and Chiang Mai.

The practice of creating networks that move across time and space is something that defines Costinas' work, which in turn feeds into the 4th Kathmandu Triennale's expansive exhibition, and the connections and threads it draws between practices from across Nepal, its surrounding region, and beyond, which Costinas outlines in the discussion that follows.

SBHow did you get involved with the Kathmandu Triennale?

CCI've been connected to artists and writers from Nepal for a number of years now, as part of Para Site's focus on expanding the geography and networks of collaboration of the institution and the understanding of our region and its vicinity.

We wanted to create a platform that placed different artistic languages and practices in the same room and the same conversation, alongside the tensions that arise as part of that.

We were trying to connect with contexts around the world, which was always the main point. But within that we tried to imagine differently the axis on which Hong Kong is placed, starting with Nepal, which is a crucial part of our expanded Asian region. From the perspective of Hong Kong, Nepal is the home country of one of the city's largest migrant communities, which is not always acknowledged.

SBHow did you come together with co-curators Sheelasha Rajbhandari and Hit Man Gurung to develop the curatorial framework for the Triennale?

CCAfter I was appointed as artistic director for the Triennale, I invited them to be co-curators of the project, which was in my view, an organic development of our professional relationship.

Hit Man and Sheelasha were my closest collaborators in Nepal. I worked with them separately as curators and artists in different exhibitions. We had long established a dialogue among ourselves, and the themes of the Triennale were developed as a continuation of that dialogue.

SBThere's an interweaving of local and global here, and an interweaving of craft, traditional cultural production, and contemporary art production.

How did you conceptualise the curatorial framework and how does it unfold across each of the five venues?

CCThe curatorial framework came from our own interests, work, and research. Artists in the show work in very different vocabularies, but also in different economies of artistic production. We wanted to create a platform that placed these various artistic languages and practices in the same room and the same conversation, alongside the tensions that arise as part of that.

SBCould you talk about how different modes and practices are brought together in each venue of the Triennale?

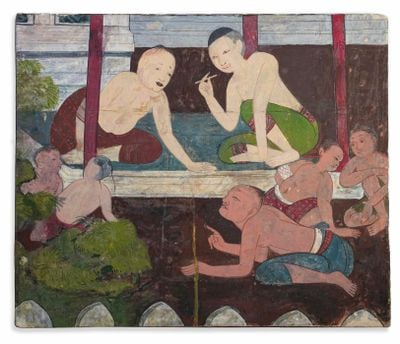

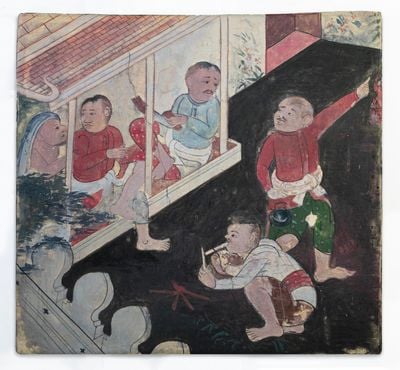

CCThe main tension happens at the Patan Museum, where different lineages are brought together in often unexpected ways. The rooms that primarily address artistic languages start with a work by Sakarin Krue-On from Thailand, who has reproduced scenes from murals of Buddhist temples in Bangkok as a series of small and delicate paintings.

In the murals of Buddhist temples in Bangkok and other religious contexts, you have scenes depicting the life of the Buddha and others representing lives of commoners, which are usually rendered at the bottom of the religious scenes. He's very interested in how these scenes depicted contemporary life to painters, rather than that of the Buddha. Most of these are 19th-century labour scenes.

That work was the starting point for our statement of interest in artistic languages, which is trying to place them in the context of the actual historical circumstances in which they are produced and more specifically, within the economies behind artistic practice and the life of the maker.

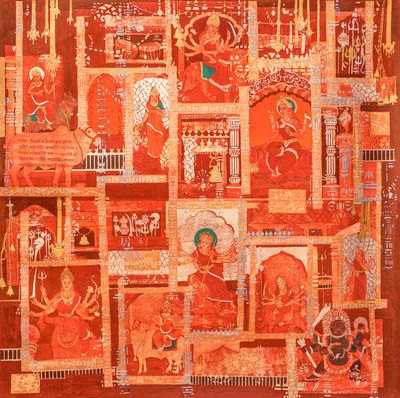

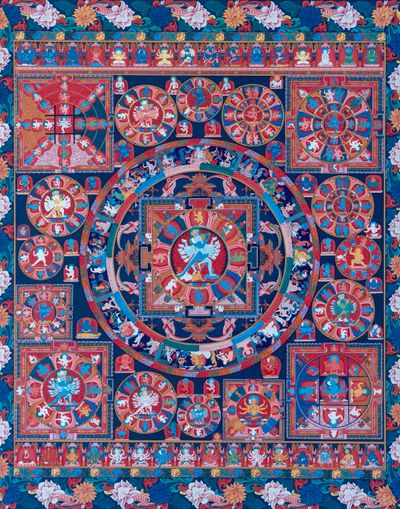

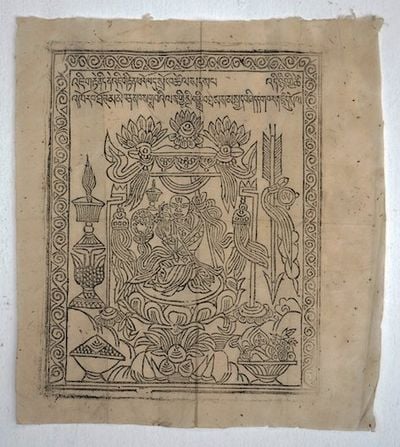

Then we enter a bigger room where we have these arresting works by Lok Chitrakar, probably the foremost Paubha painter in Nepal, which is the high-painting language of the country—one of the oldest painterly vocabularies that is still practiced, and the source of Tibetan Thangka painting.

Next to this, we have a reproduction by Jivarama, who was a master of Paubha painting from the 16th century. We try to show the historicity of the Lok Chitrakar work, as there is a clear dialogue with the Jivarama reproduction, and we also have a digital version of Jivarama's notebook, which has been fundamental to the development of this artistic language.

It was important for us to show that we were not regarding lineages as immutable ideas of things that exist outside of history.

Next to it, we have an unfinished work by Lok Chitrakar, 20 years in the making. It shows the incredible length of the process behind these works, and how they function in a different economy than contemporary artists', who tend to produce objects at a different speed and time investment.

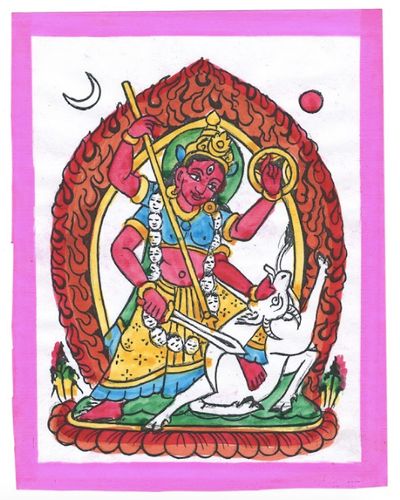

Besides Paubha painting, male Chitrakars were also in charge of a very specific healing function—to treat people who had the painful condition known as shingles, by painting two lions around the eruptions.

One can see it as a magical technology, even if there is an entire conversation about how natural pigments used to make the painting have analgesic properties.

But most interestingly, in our view, is the fact that in the caste system, the Chitrakars, who were a caste of painters, and the family name of Lok Chitrakar, were quite low in the hierarchy, not unlike the position of artists in most social hierarchies in the world.

Healing practices were reserved for the highest class, the Brahmins caste, so this was a way to transgress their social condition—a technology to subvert the caste system.

Lok Chitrakar has also set up his own teaching structure. Until very recently, you couldn't study Paubha painting in the art academies of Nepal. Perhaps because a significant part of Nepal's identity in the last half a century, prior to the Republic, draws from the fact that it was the only country in South Asia that was not colonised.

There was less political urgency to decolonise its references and its Eurocentric formal art education—less so than India, which was already revisiting its own artistic languages of expression leading up to Independence, as part of the anticolonial resistance and in the first decades of the Republic.

So Lok Chitrakar establishes this school, and he's very much part of the conversations around how it sits with other forms of artistic practice in the contemporary context, because he is one of the most prominent and probably the most involved Paubha artist in conversations across languages, and equally curious about other contemporary forms of expression.

SBI'm interested in this idea that in the Kathmandu Triennale, there is another conversation happening with traditions like Paubha painting, which takes place separately from the Academy, and from modernist canons.

CCWhat you see after the Lok Chitrakar and Jivarama introduction are two things. On one hand, there are abstract works by Puran Khadka, who was a major, even if slightly under-recognised Nepali modernist painter. He was very much inspired by and based his abstract language on his spirituality. So a very clear connection and even unity with the works of Lok Chitrakar even if their artistic vocabularies might seem an ocean apart.

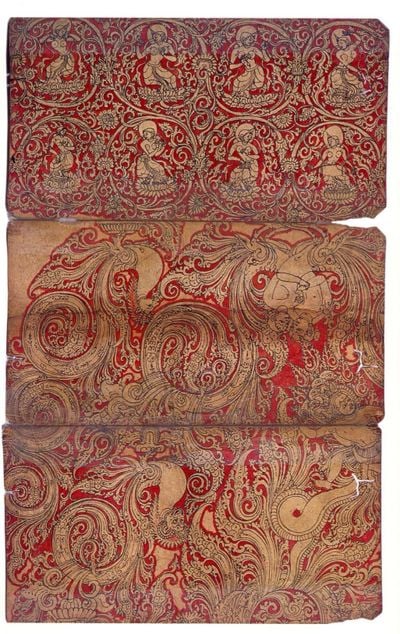

On the other hand, we were interested in how in the Chitrakar caste, men did Paubha painting and healing, while women block printed small and highly elaborate paper religious representations that are pasted throughout Kathmandu Valley, next to doors, and in specific places.

Block printing is also an artistic language that is under threat because it's being replaced by digital prints, which are much more accessible and attractive because there are more colours. We wanted to include this lineage of block printing as a commentary, both on artistic languages—because this was seen as a lesser language, but also on gender distinctions—because this was basically the work reserved for women.

So we showed the works of Chet Kumari Chitrakar in this grouping of artworks, to also direct the conversation of the Chitrakars towards gender.

It was crucial for us to analyse power dynamics and how they intervene in the writing of art history, without establishing simplified dichotomies, with 'Nepali' as one category of artistic practice separate from the Eurocentric canon, because the situation is much more complicated within Nepal's arts and in the political narratives and conversations in the country.

During the civil war and after the establishment of the Republic, a great effort was made to try to establish the basis of a pluricultural society. Within the different communities, there are different artistic lineages that have gone through varying processes of marginalisation.

Paubha painting was in a relatively privileged position; although it was excluded from the academies, it was held in one of the highest regards. Conversely, there are practices that have been altogether discarded from narratives about Nepali art and are rarely even considered to be artistic practices, so it was important for us to bring them into the same conversation.

SBIt makes sense that you would have the Chitrakar works in conversation with Puran Khadka then.

When you talk about the civil war and the establishment of the Republic, you are situating these events within this ongoing process of becoming on a world stage.

CCI think so. If you go further in the same room, you have beautiful contemporary paintings by Bal Krishna Banamala, who is a younger Nepalese artist. He was born into a caste that oversees the performance of ritual dances that are quite ecstatic.

It's a very privileged position, but it comes with a lot of restrictions, so there's a lot of tension for him that comes from being in that situation. The paintings are contemporary, semi-photographic, autobiographical representations with masses of colour that perhaps indicate anxiety.

We also included a sound piece recorded while he's in the ritual, after many conversations with the artist. A video representation of that moment would have probably been more difficult to avoid an ethnographic gaze, which the sonic piece does in our view.

And then we have the works of Hung Fai and Wai Pong Yu from Hong Kong, which bring in East Asian or Chinese ink as one of the most successful, vibrant artistic languages, that is very much part of the contemporary conversation and various artistic conversations throughout the 20th century with a genealogy outside European art history.

...there are practices that have been altogether discarded from narratives about Nepali art, so it was important for us to bring them into the same conversation.

Again, we were interested in the economy and understanding of the role of the artist behind these works, so we showed Hung Fai's works done with his father, who is a celebrated master of ink art, which is an attempt to destabilise that master and disciple relationship by showing work they created together.

Interestingly, they are not co-signed, which is Hung Fai's choice, and then there's the work he did with Wai Pong Yu, and that's co-signed. Maybe it's part of the resistance towards his father as the master.

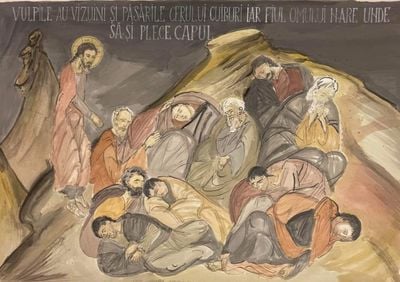

After Hung Fai and Wai Pong Yu we have works by Ion Grigorescu, a Romanian artist who was also a complex figure. While he pioneered video art and performance in Romania in the early 1970s, his works are also imbibed with his deep and rather idiosyncratic Orthodox faith, something that would become even more obvious in his later works.

He would also spend summers painting the walls of new Orthodox churches in the countryside. There is a degree of originality in those paintings, although he created them within the canon of Orthodox painting. In Kathmandu, we are presenting a whole wall primarily of Grigorescu's Orthodox paintings, which is slightly uncommon; within international contexts he is usually presented through his avantgarde facet.

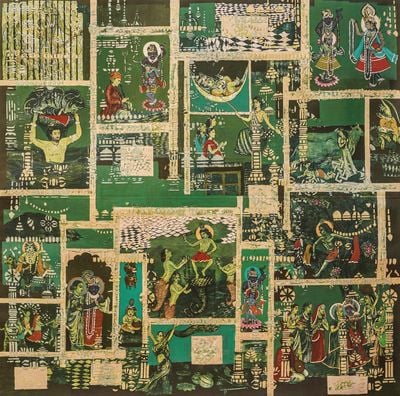

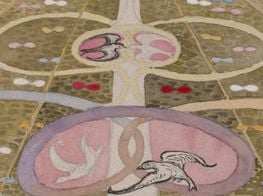

On the second level, we are showing women painters from the Mithila tradition. These are amazing works from the 1970s, which is when Mithila painting moved from a mural style to paper. This is also a painterly language that is more marginal than Paubha in the caste-influenced vision of Nepali art, so there are several degrees of power intervening in that conversation.

We are also presenting Korakrit Arunanondchai's video in a beautiful corner of the Patan Museum. The sounds of his video interfere with the sounds coming from Patan Durbar square and the temples around it.

Then we move to the top floor where we have two examples of new Indigenous visual languages, including Bon temple architecture developed in the past decades for an ancient religion that did not build temples before, and Bolivian architect Freddy Mamani's Neo-Andean work reflecting social mobility among the Aymara community in Bolivia after Evo Morales' election.

This section also includes several artists working with popular culture, including television drama and anime culture. These not only intervene in religious representations, but within entire generations from South Asia, East Asia, and other parts of the world. These TV programmes have been the main source of education about the mythologies of their cultural contexts. I think many in Hong Kong have also become familiar with great Chinese classics through television series.

Then we move to the second wing at the Patan Museum, the Sundari Chowk, where there are several rooms presenting works by artists engaged with Indigenous traditions around the world.

There's also a Hong Kong room—part of Patan Museum was used as a prison, so there's a room where messages left by prisoners on the walls are on display. That's where we're showing Lam Tung Pang's eerie paintings of Hong Kong.

We also have works by Chan Kwok Yuen there—a master of Cantonese opera costumes. We are showing headdresses that represent characters from the different Han, Tang, Ming, and Qing dynasties.

We're also interested in how that sense of continuity in Chinese history over the course of 2,000 years is embedded within the tradition of this semi-vernacular medium of Cantonese opera.

And then there's a whole section with a feminist focus on various women praxes, and the female body as a means of expression—from Ana Mendieta to Ashmina Ranjit.

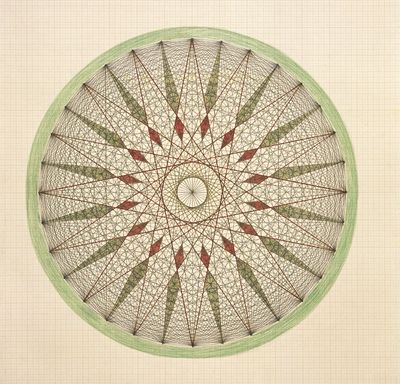

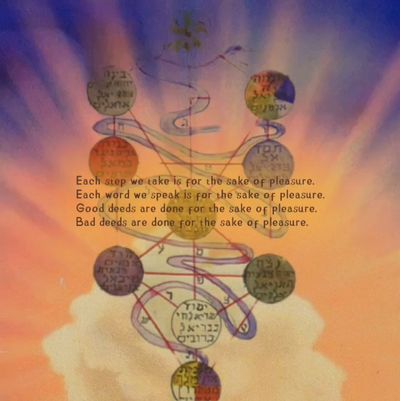

Further up, we move to a section interested in a multiplicity of healing methods, where we have objects and practices deriving from a variety of medical imaginations, including Emma Kunz and Batsa Gopal Vaidya, who is another senior Nepalese artist working in abstraction, albeit quite different from Puran Khadka—less of the modernist interest in forms and more deeply spiritual, inspired by the Ayurvedic traditions of his caste.

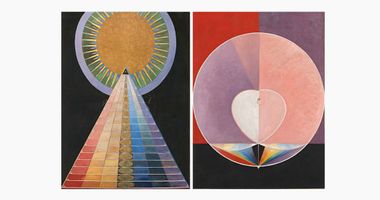

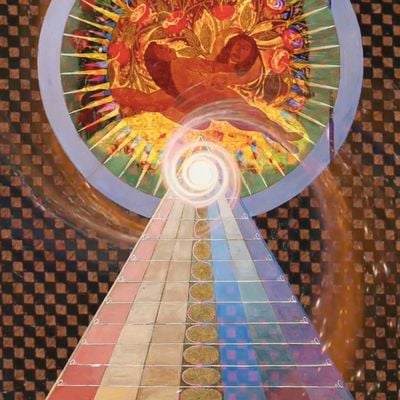

SBIt's interesting that you bring up these artists, because works by Emma Kunz and Batsa Gopal Vaidya speak to Simon Soon's Ocean of Wisdom (2021) at the Taragaon Museum, which meshes visuals by Hilma af Klint with other visual traditions.

Did you think about this? Because when you're speaking about Paubha paintings or ritual dance, it taps into a universal, but not necessarily the Western universal.

CCAbsolutely. Simon Soon's beautiful video collages would have worked very nicely there. We included them at the end of the Taragaon Museum because we wanted to refer to the museum's archive, which consists of anthropologists and ethnographers, mostly European, looking at Nepal from different perspectives—many of them from that of architecture and heritage. We invited Simon there to do his own research as somebody looking from a very different perspective.

SBCould you talk about the Taragaon Museum? The garden as a metaphor is very present in works here, including Uriel Orlow, Sunita Maharjan, and Trevor Yeung's site-specific installations, providing a way to think through networks and space organically—as soft and malleable rather than immutable.

CCThis was one of the threads explored in the Triennale—to look at gardens and cultivation as cultural objects and as culturally specific processes.

In the colonial project there was a large focus on the trade and cultivation of seeds, and the trade of people who were enslaved to work on these plantations. So gardens can be considered as cultural objects in relation to items of trade and plunder, also thinking about the chinoiserie gardens in Europe.

And of course, more broadly, gardens have been at the core of many cultural spaces. We're interested in how this cultural specificity, both in garden design and agriculture processes, reflects a broader understanding of the world.

The arrangement and understanding of a garden are inscribed in a broader logic of thinking about the individual's position in society, in the world, and in the cosmos, and sometimes the inner workings of the body and soul are on the same axis, with the garden somewhere in the middle.

So for us, this is the same conversation as the one in the Patan Museum about artistic languages, which are not just isolated expressions of human difference; they're all inscribed in bigger systems of logic and cosmologies that include different understandings of nature and medicine.

Because the small section that shows different examples of medical imagination at the Patan Museum—which, again, is not just about celebrating the diversity of humankind, but pointing to different and broader scenarios of how to live, how to imagine your place in the world, how that's manifested in how you cultivate your food, how you design your surroundings, and so on.

I think if we are genuine and radical about decolonisation, we have to take all this into account and understand both the multiplicity and the totality of each of these ways of thinking.

SBThe garden metaphor is useful when thinking about decolonisation as a means to work out of complex, but embedded entanglements that are as organic and intersectional as the constitution of the earth itself.

CCIt was important for us to show that we were not regarding lineages as immutable ideas of things that exist outside of history, but as things that change and are in constant processes of invention.

So we showed the work of a Gurung architect who is part of this very interesting process happening in the past 30 years within the Bon religion, which is the ancestral religion of the Gurung people and the Indigenous religion of Tibet prior to Buddhism. It still exists in various forms, both in Tibet and in the Gurung community.

As part of the overall process of re-establishing the Nepali nation in plurality, away from a unifying kingdom with one language and one religion, Bon believers decided that they wanted to develop temples for a religion that never had temples and was always practiced outside this structure of a building specific to religious services.

Several architects in the community developed a new language for Bon temples based on pre-existing sacred forms, and temples were built across Nepal. There's also one in Dubai, and there are conversations to build one in Hong Kong. It's quite a unique process where an ancient religion develops a major new language for its practice.

This is connected to Freddy Mamani's works nearby, who is a Bolivian architect who developed this particular style of Neo-Andean architecture. It's very much an architecture of the present, connected to the new elite that was able to flourish in the country after the election of Evo Morales.

SBThis brings to mind the curatorial at the Nepal Art Council, where works by Mohamed Bourouissa, Aziz Hazara, Pacita Abad, photographs by Nagendra Gurung, a Nepalese worker in Saudi Arabia, and a large textile from Tonga by the Women's Group Kautaha Halaleva, are all placed in this very broad conversation that reflects a running thread across the five venues, which seems to weave the local and the global into a trajectory of modernity.

CCIn this venue, we're showing artists working in vocabularies for which there is already a generally accepted code of translation. Besides Nagendra Gurung who works primarily as a construction worker in Saudi Arabia, all the others here are working within the system of contemporary art.

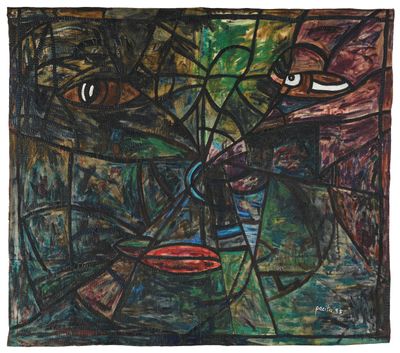

Alongside the works of Nagendra Gurung, Pooja Gurung, and Bibhusan Basnet, which illustrate different aspects of how migration affects Nepal, within the country and its villages of origin, respectively, there are the works of Pacita Abad, reflecting the plight of migrant Filipino workers.

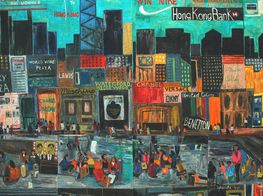

Moving further, there are several artists depicting disaffected youths who are often left outside or at the margins of the economic system of labour.

So you have Mohammed Bourouissa's community and youths in the banlieues of Paris; you have the working class and migrant workers from Central Asia in Moscow in Olga Chernysheva's works; you have Karan Shrestha depicting youths coming to Kathmandu from all over Nepal; and you have Aziz Hazara's work, which is also about two young boys at leisure, playing, albeit more ominously than the others.

SBThese all speak to the theme of migration staged at the Nepal Art Council, which extends to the textile works that are also here.

CCWe have some batik textiles next to works dealing with migration at the Nepal Arts Council. Those are the Malay Singaporean versions of Javanese batik that were bought by Nepali men working in Malaysia and Singapore and taken back to their communities in Nepal, becoming part of local dress. The migration of people also facilitated the migration of forms.

The next venue is the Bahadur Shah Baithak, which primarily looks at mapping and forms of representing both the cosmos and the earth, as well as social structures and different kinds of interiorities.

SBCosmologies.

CCYes, at different scales. We also have works dealing with infrastructure and works informed by various systems of navigation within the representation of the cosmos. We commissioned this great piece by Köken Ergun and Tashi Lama in the language of Nepali Tibetan painting.

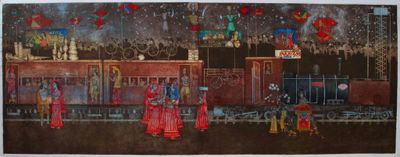

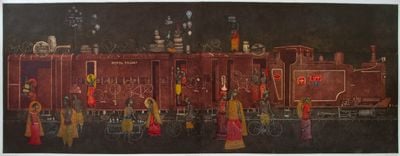

The triptych represents infrastructure projects that are part of China's Belt and Road Initiative, and it's shown next to a work by another Nepalese artist, Uma Shankar Shah, who looks at the first train developed in the country.

We also have an Asafo flag from Ghana that represents a train. We have the works of Subas Tamang that look at how the first cars bought by the elite in Kathmandu had to be carried on the shoulders of people from his community, because there were no roads leading into the city. Cars were brought into Kathmandu to be used only on the city's streets, but they had to be hand-carried here.

There is also the work by Liliana Angulo Cortés from Colombia, who is working with activists and looking at different hairstyles in the African diaspora and how these represented escape routes for people during enslavement.

Secret codes were represented in braiding patterns, which were used to indicate what routes to take to escape and establish new maroon communities of freedom, many of which remained in the braiding traditions of the diaspora.

Next, there is the Siddhartha Art Gallery, which is a smaller venue where we're showing works that delve into different instances of natural and man-made catastrophe, and the resistance and persistence around them, starting with the devastating 2015 earthquake in Nepal.

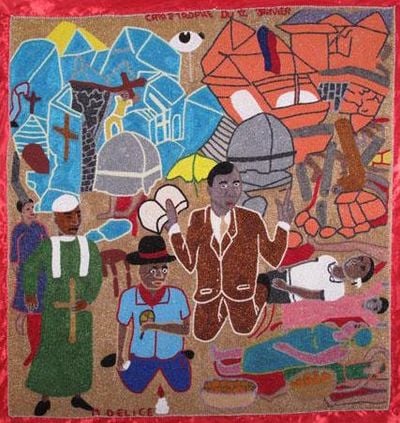

A Vodou flag composed of sequins and beads by Mireille Delisme from Haiti is on view in this venue as well, memorialising the 12 January 2010 earthquake in the country.

SBWhen there are different trajectories and different traditions in one space, the tendency would be to see these things in concert or in dialogue. People will find their frames of reference to interpret what they see and the connections they hold. How do you mediate that?

CCThe Triennale is positioned in the context of Nepal, where the core conversation has been about how to establish a federal nation of different communities. The gesture of sitting together in a room in difference is very much part of the public spirit in the context of Nepal.

So there was nothing radical about our proposition. It was more about trying to really understand the implications of major discussions that were already happening in the Nepali context, and to do it from the perspective of art.

Of course, one can argue that in different ways, there's a global conversation happening that considers how to bring together different lineages and decolonise the frames and references we are working with. —[O]