Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg Dig Deeper in Shanghai

Lisson Gallery | Sponsored Content

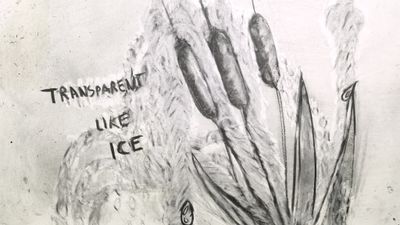

© Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg. Courtesy Lisson Gallery. Photo: Wynrich Zlomke.

© Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg. Courtesy Lisson Gallery. Photo: Wynrich Zlomke.

A Stream Stood Still, Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg's first solo show at Lisson Gallery's Shanghai space marks a turning point of sorts, which they explore in this conversation that reflects on their evolution in recent years.

Djurberg and Berg began working together in 2004, and are known for creating immersive, landscape-like installations that amplify the textures of the subconscious through stop-motion animations or claymations, flora and fauna sculptures, and soundtracks by Berg that expand into spatial, sonic, and affective sensory realms.

The artists' exhibition in Shanghai (24 February–7 May 2022) assembles 14 new sculptures made of blue branches hosting plant life that frame a new charcoal animation, Like beads on a string (2022). Depicting tears that move from a forest to the ground below it, this marks a return to charcoal animation, which composed some of Djurberg's earliest animations.

As Djurberg notes, the shift to charcoal reflects the textures of sadness that frame A Stream Stood Still, which follows the artists' recent survey show A Moon Wrapped in Brown Paper at Prada Rong Zhai in Shanghai (11 November 2021–9 January 2022). While rooted in the conceptual site of the forest that has featured consistently in Djurberg's claymations, the tone and subject matter of this new work departs from previous tropes.

Take Dark Side of the Moon (2017), a surrealist compression of fairy tales set in the woods, from Little Red Riding Hood to The Three Little Pigs, that tells the story of temptation and desire; or Delights of an Undirected Mind (2016), which lends its title to the artists' upcoming survey at Kunsthalle Luzern (2 April–19 June 2022), where anthropomorphic animals fondle each other in a child's bedroom.

It was in 2009 that Djurberg and Berg created their first major installation, The Experiment, which was awarded the Silver Lion for best emerging artists at the 53rd Venice Biennale. Conceived as a prehistoric jungle, sculptures of giant plants framed a trio of body-horror claymations that told a corrupted genesis story—all tied together by Berg's ominous score of crickets, waterphone chimes, and a warped and wailing low horn.

In Greed, bishops oversee naked women tearing off each other's flesh, while Cave depicts a lone woman dismembered by her own limbs, as an elderly Adam and Eve are ravaged by tarred earth in The Forest.

A sense of debased desire, predatory violence, and perverse power relations charge unhinged animations that ambiguously walk the line between innocence and traumatic experience. Whether in Tiger Licking Girl's Butt (2004), showing a young woman in her bedroom harassed by a jungle cat, or in We Are Not Two, We Are One (2008), in which a young boy must share his legs with the body of a fearsome but sorrowful wolf.

What is expressed across works, beyond the constant charge of violence and distress, is a carnivalesque tableau of unease, discomfort, and shame—dynamics that extend to The Parade (2011), commissioned by the Walker Art Center and later shown at the New Museum in 2012.

A group of five animations screened amid sculptures of giant, multicoloured birds made from painted canvas, wire, and clay, included I wasn't made to play the son (2011), showing a woman being cut, torn, and pulled apart by masked men.

Djurberg notes that her animations have softened over the years. The 2019 exhibition One Last Trip to The Underworld at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery (1–20 December 2019) reflected that turn in particular.

Among four claymations screened amid multicoloured sculptures of birds suckling at giant flowers, was the mesmerising One Last Trip to The Underworld (2019), showing a woman hypnotised by an octopus who puppets her dancing, and This is Heaven (2019), the tale of a man's greed that unfolds in the bright candy colours of a cloudy paradise, to a score invoking Chariots of Fire.

Similarly, the dynamic between Djurberg and Berg has also evolved. Projects like The Black Pot (2013) saw Djurberg creating visuals in response to Berg's music for the first time, resulting in organic shapes on screens and giant, sculptural eggs in space, while both note a marked difference in dynamics when composing Like beads on a string.

The artists touch on those changes in this conversation, which tracks a singular and inimitable collaboration that functions across registers, where personal experiences are filtered through a shared space of making.

SBLet's start with your show at Lisson Gallery in Shanghai. Among the 14 flower sculptures you have created, you are also presenting a new charcoal animation, Like beads on a string, which is interesting, because some of Nathalie's early animations were made with charcoal, right?

NDYes, some of the first animations I made were in charcoal, but not the very first ones. I haven't done many charcoal animations as they are quite time-consuming and heavy, and not as direct as claymation.

But for this show, claymation didn't fit the concept. I couldn't turn the idea into clay, so I had to make it with charcoal. I couldn't have done it another way—I almost didn't want to do it another way. Charcoal is calmer, and this charcoal animation is very calm.

SBCan you describe Like beads on a string?

NDThe animation is about crying—about deep sadness and grief—with tears falling and texts forming from the drops, and making a mess out of drawings, which go from a dark forest to a close-up of leaves, to an animal and an eye.

Drops or tears are falling on the leaf and the leaf bounces and then more tears fall and then you see an animal crying. Then the drops fall on the ground like rain, and they seep through the ground, through the roof, and drip further down to hit a diamond.

Just as I was about to animate the work, my father died, which in turn made the work deeper. It felt quite right to sit and animate this as it was happening.

HBIt's a poem, I would say.

SBGrief is an unbearable shapeshifter, and it's moving to hear how you channelled that into the animation.

It made me think of how the forest or the garden have long been staging grounds for your animations, Nathalie; an emotional terrain where you explore your subconscious. In fact, your first show in China, at Shanghai's Minsheng Art Museum in 2016, was called Secret Garden.

NDYes. The animations and my emotional state always coexist. I can't get away from the emotional state they display. As the animations are made, sometimes I don't see the emotions, but sometimes I do, because I am living through them as I am animating.

The most surprising reactions have been when people are touched in a way that they didn't think was possible...

For example, when I made Dark Side of the Moon, I was going through such turmoil, confusion, and frustration. It's the only animation for which I had to take a break for a few months. I was lying on the floor because I didn't want to make another image. Then I had to start up again.

As time goes by and I look back at the work, I have begun to understand what I was going through. It had to happen, and that became the animation.

SBThis relates to one of the things that I've read about you, Nathalie; that you prefer the theories of Carl Jung over Freud, which makes sense.

While Freud projected a lot onto his subjects, Jung was interested in what our subconscious could reveal, which relates so much to the process behind your animations, which you often describe as a journey into the unknown.

Hans, with that in mind, could you talk about your experience of creating sound for Nathalie's animations? Because you're effectively being invited to enter a very personal, emotional space.

NDYou're always in my personal, emotional space!

HBYeah. I always say I can't avoid it. But then again, I have my own personal space that I come in with. I can't step into another person. I can't step into Nathalie's mind. It's going to be my interpretation either way.

SBHow did this manifest in Like beads on a string?

HBWith Like beads on a string, we had a lot of discussions about the sound. Clay animation has qualities that are very different from charcoal animation. Charcoal animation can be a lot more intimate, as is the case with this one.

Clay animation can be too much sometimes. Too much texture, too many colours, too many things going on. And it's a bit comical. Sometimes I think it can be hard to make something very serious, intimate, and clean with clay animation, but it can be achieved using charcoal.

This is what I am thinking when I am making the music. I didn't want different instruments and a whole cacophony. I want the music to be very precise and very close.

For this piece, Nathalie and I discussed the music a lot, and what to do with it. Nathalie had a lot of ideas that she wanted to include.

NDI usually don't. But this time I wanted to try it out. I haven't been pushing for 15 years, but this time, I did.

HBYeah. Some things I kept, some things I didn't.

NDAnd I was fine with that. Because I also know that what I think or feel is secondary when it comes to the sound, and Hans knows best. So when he says something doesn't work, I'm fine with it.

HBI make music not only for the film, but also the installation and the exhibition as a whole—I keep in mind the sculptures that extend from the film into the space.

For Like beads on a string, I made the music four times longer than the film. The film loops four times before the music starts again, because it's more intimate and minimal, and every time it restarts there are small changes.

SBCould you talk about the process of composing the music, Hans?

HBThere is a lot of thought before I start with the actual composition. In a way, the most important work is done before I touch an instrument; thinking about the whole idea of what the music actually is, what it does, what it represents or conveys.

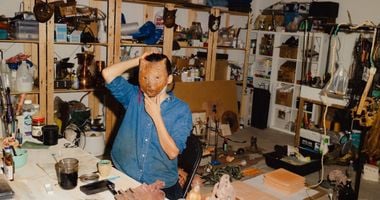

Then I start with the tonal image of the music, collecting sounds, instruments, and considering how it should sound. Finally, I compose the actual music. At that stage, the animation is usually finished and I have it on my screen in my studio and compose directly to it.

I play everything myself, for instance the flutes I used for Like beads on a string come from a sample library, meaning I can play them on my keyboard in my studio. It's not the same as 'real' instruments, but that's not really what I'm after. I always manipulate the sounds in some way to achieve the exact sound I want; that I think works best for the film or installation.

I like mixing acoustic instruments with synthesised sounds to create a world that's not quite easy to define, as is the case with the films and sculptures.

SBThinking about how you collaborate with Nathalie on the sound, it's interesting to hear that Like beads on a string marks the first time in a long time that you've had more of a tension in terms of how the visuals and the music worked together.

In the beginning, it was very much Nathalie inviting Hans to respond to her images, but then Nathalie described letting go of control in recognition of how Hans' music changes and expands the work.

Considering how you have entered each other's worlds, I'd love to know how you both navigate your collaboration.

NDI had already done animation and Hans already made music, but he was almost invited into my world where I was the boss. I was very solitary and quite reluctant to invite somebody into my process and share what I was doing.

Once I started sharing, Hans changed the work. There was no jealousy. I started to throw works at him.

But I was also quite dominant, telling him what to do. It took some time to understand that I had to let go of control, that he was bringing something that I didn't have. I had to let go to create something new. When I look at the collaboration now, it's more like I have my process and he has his, but that space where it's shared is almost its own entity.

And that is very enjoyable because there's no real ownership. It's its own thing. It came to a point where it felt incredibly wrong not to have his name there. I might not have felt it then, but it was also a relief. Not to be there alone, but having someone with you.

HBI like what you've said. That after a while, it created its own space. Its own entity with no specific ownership, although we have clearly distinct roles.

NDThe order of the music doesn't really matter anymore because it's a single thing. It's looser at the edges now.

I think we both appreciate that third entity, so we let it be. We don't need to add fear to that. Fear comes by itself. It's about letting go of control. At first, so much for me was about understanding what I was holding on to, what I was trying to control, just making enough to work.

For the charcoal animation, I had thoughts, and I was pressing. I didn't want to, but it's also important to do. Sometimes I'll do that with myself, and we are always free to include the ideas, or not.

HBYeah. There's no prestige in being right, either.

SBThe Black Pot was the first time you reversed the process: when images were made to the music and not vice versa. How was it for the dynamics to be inverted in that way?

HBIt was important to acknowledge the importance of the music. For me, that was the biggest step: that the music could play the main role and not just accompany the films. While the music played a large role before, it was never explicitly mentioned.

NDYeah, exactly. Never said out loud.

HBSo the music became the main character and this was the first time. It doesn't have to be like that every time, but it showed that it could be.

SBWould you say that Like beads on a string marks a turning point, given how the dynamics between you have changed?

NDI don't know, because it changes all the time. But at the same time, it follows an invisible path. Every time I look back, I see a path that I was not seeing in the future.

So much has happened in the last years, which have been really turbulent both personally and generally. With that comes a lot of change.

SBOf course, Nathalie you also became a mother recently, right?

NDYes, that was also a turning point in a way, whether in terms of longing for work, learning how interesting choosing a carpet for an exhibition could be, or just being forced to feel more.

It's overwhelming, becoming a mother. It's so hard. Now I have much more compassion not only for women, but in general. I guess hormones play a role and enhance this.

Whenever I feel like I'm in crisis for not being able to work or do the things that I normally do and that I also love—because I love working and working is also an emotional escape for me—Hans is there to remind me that the living also needs to happen.

SBLooking back at your animations, we go from dark Hansel and Gretel forest settings where the dynamics of violation unfold, to spaces like those in Worship (2016), with scenes cutting from dark, seedy spaces to a bright pink studio and daylit stadium.

That shift between environments, and dark and light tones, really came through in your 2019 show at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, One Last Trip to The Underworld.

One animation, Damaged Goods (2019), splices between a female creature in a dark room assembling herself by pulling out props from a box, and a cam girl in a soft, pastel blue boudoir. Then you have This is Heaven, which is an explosion of candy colours.

Thinking about that trajectory from then to now, could you talk about how your environments have changed?

NDI feel like I have always been quite childish, always also caught up or stuck in imagination and have difficulty handling reality, and art has been a way for me to make sense of life and explore.

When the works for One Last Trip to The Underworld were developing, I was in mid-transition. My life was changing and I was going through something that felt almost like breaking apart.

So it went from childhood, this Hansel and Gretel setting, as you call it, into these crisp spaces that were painful for me. Incredibly painful—like you would want to stay in the forest but you've been transported away from the forest, where you've lived your whole life.

I feel like there is a red thread that goes through the practice; that touches the same points again, but from another angle.

SBThen we reach Like Beads on a String, where you've come back to the forest to mourn, which relates to the personal journey your animations track.

Whereas earlier works explicitly explore the dynamics of trauma through clear oppositional dynamics, you've described the line between victim and perpetrator becoming less clear in later works like Worship and One Last Trip to The Underworld.

Things become more dialectical; a question of what happens after the trauma has been inflicted.

NDYes. I absolutely know what you mean. I think in the earlier works there is a very direct, rock and roll edge: it's getting it out, getting rid of it, and getting it out there. Then it becomes more careful and softer—it almost turns.

It's always tricky, knowing what you want other people to know or how much to say, because it's an interesting but vulnerable subject.

HBI think it's a deeper understanding. As you look at these roles so many times while making the films, I think it gives you a deeper understanding of those roles.

It's not just victim and perpetrator, they get mixed up a little bit, but even then, it's a push and pull relationship; you notice complex nuances within these roles, which become more apparent in later works.

NDIt's also about switching over to the pain of victimhood. The pain of not being able to, for example, step out of an addiction, no matter what kind of addiction—emotional, physical, or with substances.

SBThis relates to that one line in Tiger Licking Girl's Butt: 'Why do I have this urge to do these things over and over again?'

One of the worst things about trauma is not realising that you're traumatised—you become wired into behaviours that feel beyond your control, which kind of equates to addiction.

Hans, you described the music for One Last Trip to The Underworld as being based in addiction; those hypnotic sounds equate to chasing the dragon, like dancing with demons.

HBThat's exactly the idea. And it was also the idea behind the film title, One Last Trip to The Underworld. It's like chasing the dragon. Just one more hit. Or just hoping it's the last trip.

NDOr just hoping it's enough.

SBThe subtext across your works in this sense is this grappling with longing, entitlement, and desire, which can relate as much to someone claiming ownership over something as it can to someone taking another's body for themselves without permission, or someone being caught in a loop they feel they have no power over.

NDAbsolutely. When it comes to our collaboration, the works with Lisson Gallery for instance, when I was going through what I was going through and making them, Hans brought along grief and sorrow from his own past that were deeper than mine.

I think that there's always been a silent understanding between us. We have never been through the same things, but I'm grateful for what he brings, which is something else—another understanding.

HBOf course, we talk about the work a lot, so we do know what's going on. But I think it's also because we are two people, so the focus is less on you Nathalie, and it's less of a personal exploration in a way, because we are two.

NDYeah. It's good because some of that is taken away.

SBThis relates to another dynamic in work together. Nathalie, you mentioned how, before collaborating with Hans, you were very much in your own space—a space that really comes through in the animations as documents of working through trauma.

NDYes.

SBIn that regard, bringing Hans into the work almost feels like a necessary part of that processing; to create a space of healing in which the male archetype so often represented as abuser in your work, is countered by the presence of a man who is actually a safe space—who actually works with you to create that space to process.

NDYes, that is true. I'm a very scared person. Fear and shame are emotions that are really, really strong in me. But Hans is the one who made me able to function in the world. By him being who he is, he taught me to be less afraid and to dare to go out—to dare to live.

And that fits very well with the work. But I think that for both of us, work and life are so intertwined that it's almost impossible to pull them apart.

SBI read one article that described your partnership as confounding to the art world, because it's not a collaboration in which a single work is being made.

It's an assemblage of positions—your subjectivities, your talents—that creates a space for you to make work together as individuals, not as one entity, which raises questions around authorship.

NDYeah. It has to do with the idea of the genius or divine inspiration, or the solitary tortured genius—this idea that an artist should be a single person. I sort of agree with that. It's a very personal inspiration, of course. But in the process of creating, Hans and I have our own creativity, and then it just comes together. It felt really wrong after a while not to have his name on the works.

HBOwnership or authorship is shared. Even though I would never make an animation, there's so much discussion back and forth, all the time. The ideas are really intertwined. Because we're two and we both have our inputs, it adds complexity to the work.

SBThat intertwining comes through on multiple levels, whether in terms of collaboration or what is produced between you.

But there is another aspect that I wanted to dig deeper into. Hans, given your music responds to works that explicitly address male-on-female violence, how do you relate with Nathalie's animations?

HBI'm very much aware that there are experiences that I can't have or understand. On the other hand, I can only bring myself. Of course, I'm trying to be as aware as I can about these experiences, but in a way, I don't have to, because I'm not changing the film. I'm just adding to it.

I think that for both of us, work and life are so intertwined that it's almost impossible to pull them apart.

NDBut you are more aware than me, or you're more intellectual than I am, and you're still part of the work. So even though it's not your personal experience, when it comes to, for example, violence against women, you are still part of the world where it's taking place. It's not separate from you either.

On the other hand, the other perspective you have as a man in a world where men are usually, but not always, perpetrators, is that you have to deal with that. In a way, that is just as important because it has to be dealt with, as you are born into that.

HBThere are many structures that we need to consider and be aware of.

SBTo extend on what Natalie was saying, this relates to how empathy infuses your music, Hans. You are the first person to empathise with the content of the animations, and you translate it into an affective, spatial experience. As you did with Like beads on a string.

NDYeah, the music sets the tone because the music goes straight into your feelings and influences them—it's the thing that hits you first. It sets the stage. Then you see the work and then your brain starts to analyse what it is you're watching, but you're already affected by the music.

HBOf course, I don't know how people will react to the music. I'm not trying to control it. People have very different reactions to music because it's an emotional trigger.

SBThat comes back to the Jungian perspective. You often position yourselves as being more interested in how audiences read your work than your own interpretations.

This at once creates an open space of meaning but also protects you from revealing too much about yourselves that could limit how or what a work communicates. You hold a space for the personal to remain personal both for yourselves as artists and for audiences.

NDYeah, because you cannot determine what someone else's reaction should be. I always feel like I'm slow; that it takes time for me, and I don't have answers. So how can I say what is right for someone else to experience? When there is an experience happening, when there is a reaction, it must be right. That is what is happening.

It might be pleasant for the one watching—it might reveal something, or it might not. But that is interesting. That is where art is created when it has left the studio.

Maybe it's scarier now because I'm more sensitive to what people experience these days. I feel rawer in a way, and that is affecting me more; the thought of another person watching, or the thought of what they are going to experience.

SBThinking about how you've evolved as people, how have you experienced recent exhibitions that bring together bodies of works from the past? What has been revealed to you?

NDI almost always go through a period where I feel so much shame about the work. But as time passes, I start to like and sometimes even start to love the works again.

I feel like there is a red thread that goes through the practice; that touches the same points again, but from another angle. It's also interesting to put an exhibition together and see how two animations can be put together, sometimes not really knowing why.

If you take two very different works, they may not fit so well, but when you can create this sort of puzzle or maze, it works, and I really like that.

HBIt's almost like going through an old diary, when you see the old works. Like, 'Oh, I was thinking this, of course, for this situation, but I wouldn't do that now.'

I can see the reasoning and I can see that things have changed, but it doesn't mean that they are better or worse. Works represent different stages, but they are connected.

SBWhat responses have surprised you when it comes to how people have responded to your work?

NDI have a few in mind, but I can't share them because they are personal for the people I've talked to. I have to answer in a general way.

The most surprising reactions have been when people are touched in a way that they didn't think was possible, and it comes up after; or when they have a completely different interpretation than I had while making the work.

HBPeople have various personal experiences we can't know about. But they connect it to something, a very specific thing. And that's beautiful because then you can also see it when they share it with you.

We're so alike when it comes to emotions and feelings. The whole point is to make the work as honest as possible, because if we're honest, people can relate. I'm not saying it happens every time, but at least there's the opportunity. —[O]