Simon Starling

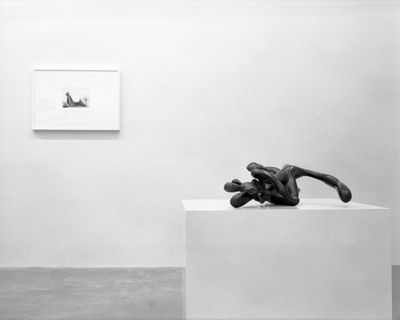

Simon Starling. Courtesy Casey Kaplan. Photo: Andrea Guermani.

Simon Starling. Courtesy Casey Kaplan. Photo: Andrea Guermani.

Simon Starling's work is defined by transformation. Whether through complex or simple means, his oeuvre reveals the curious dimensions of how we relate to material, art, and history. Nothing is neutral—even substances as basic as salt and water can be couched in intrigue. When I first saw the artist's Project for a Rift Valley Crossing (2015–16) at Nottingham Contemporary, where it was shown as part of Starling's major solo exhibition The Grand Tour Season Two Project for a Rift Valley Crossing (19 March–26 June 2016), surface and vessel were separate. The work at this stage consisted of two discrete sculptural parts: a magnesium canoe, propped up on a stand made from its shipping crate; and two giant plastic caddies filled with water from the Dead Sea—the world's largest source of the element, and the site of ongoing political conflict. After the exhibition's close, Starling united these components in a single journey, paddling the canoe across the sea it was made from.

One can trace the Project's lineage a decade back to Shedboatshed (2005), which saw Starling dismantle a shed to build a boat to row to the Kunstmuseum Basel, where he took the boat apart to build the shed once again, now bearing the scars of its journey. The pilgrimage, with its concise self-sufficiency, won him that year's Turner Prize. Another echo can be found in Autoxylopyrocycloboros (2006), a charmingly slap-stick yet profoundly ecological voyage. Setting out across the deepest stretch of the Clyde Estuary, Starling sank steadily in his fishing-boat as he burned its chassis for fuel. The work's title extrapolates from the ouroboros, or snake eating its own tail—a symbol for constant consumption and endless resurrection.

At the Rennie Museum in Vancouver a recent exhibition of Starling's work from the collection revolved around moments revisited. Included in the exhibition is Pictures for an Exhibition (2013–2014), which consists of 36 photographs featuring the 19 sculptures that appeared in a 1927 Brancusi exhibition at the Arts Club in Chicago. The artist travelled most of the globe in search of the sculptures, photographing them in their present day context, whether in public museum or collector's residence. Starling's preoccupation with a moment seemingly lost to history is hardly nostalgic. Instead, sleuthed connections see the 'art economy' unabstracted. Collectors' anecdotes, displayed alongside the photographs, detail the human desires that drive art market exchanges.

Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) (2011), which was also included in the Rennie exhibition, examines the history of an object too—this time Henry Moore's Atom Piece (1964–5). An icon of British modernism, Henry Moore is best known for figurative or natural forms that, in their abstraction, reach toward the universal. His cross-cultural appeal, Starling says, made Moore 'the first British artist to truly have a global career'. Project for a Masquerade explores the stranger-than-fiction acquisition of Atom Piece by the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art and, more broadly, the trans-national movement of modernism at large. The sculpture would become a working model for Nuclear Energy (1967), commissioned by the University of Chicago to commemorate the world's first nuclear reactor. In spite of Moore's denial of destructive influence, Atom Piece's unshakeable association with the atomic bomb continues to be controversial in Hiroshima today.

Starling's Project for A Masquerade consists of eight wooden masks, produced in collaboration with Noh mask-maker Yasuo Miichi, hanging head-height on stands. Each represents a character in the history of Nuclear Energy, from the obvious (Moore himself) to the unexpected (KFC's Colonel Sanders). These face a vast mirror which doubles as a projection screen; on its reverse, a film threads together the work's divergent trajectories. The history of Nuclear Energy is one of duplication and intrigue—one of Moore's key curators was exposed as a Cold War spy living a classic 'double life'. Starling connects it with Eboshi-Ori, the 16th century fable of reinvention, as both stories reveal how conflicting meanings can flock to a single object. Through this poetic entanglement, expansive systems are made clear—a universe is revealed in an atom, an entire history through an allegory.

Project for A Masquerade is the foundation for Starling's continuing fascination with Japanese Noh theatre, seen most recently in At Twilight (2016), his reinterpretation of W. B. Yeats' At the Hawk's Well (1916). Mourning the disappearance of ritual from modern theatre, Yeats saw Noh's stylish mysticism as a tonic for the era's social dramas. At the Hawk's Well was his effort to reconnect with the spiritual realm. In At Twilight, Starling tells a story of the play's writing as well as that of its writer. Masks, carved too by Yasuo, depict Yeats' friends, patrons, and artistic peers; 'mind maps' of associated photographs and correspondence extend the circle of influence. In a mesmerising, seven-minute video set to the clash of cymbals and horns, Thomas Edwards of Scottish Ballet swoops and stomps in a hooded bird costume, reimagining the largely undocumented choreography of the original play. Divergent yet firmly grounded in the historical, At Twilight operates in a similar manner to Project for a Masquerade, illuminating a single history's many twists and turns through a parallel retelling.

Starling was born and raised in the United Kingdom, where he attended Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham, and the Glasgow School of Art. He now lives in Copenhagen, Denmark. At the time of our conversation, he'd just returned from Japan, where he learned how to turn the charcoal from the Glasgow School's recently, and tragically, incinerated library into a fine black lacquer. This, Starling explained, would be used to paint a mask which would go to auction in order to fundraise for a new library, an adoption of his work's main themes.

AQYou recently wrapped up At Twilight (2016), a reinterpretation of the W.B. Yeats' play At the Hawk's Well (1916). Among many things, your production emphasises the impact of Japanese Noh theatre on Western modernism. Tell me about your ongoing relationship to this theme—first addressed in Project for a Masquerade (2011).

SSIt's quite a long story now, actually—and an ongoing one, too. It keeps drawing me back, Japan. Well, where to begin? I was invited to Hiroshima by Yukie Kamiya, then-curator of the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. There, I discovered that Henry Moore was an important character in the museum's history and collection. They have his sculpture, Atom Piece (1964–65), a smaller version of the work created to commemorate Chicago's first nuclear reactor, Pile-1, and the beginning of the atomic bomb project. The presence of that sculpture in Hiroshima is a very strange thing for this reason. In Chicago, it celebrates the beginning of the nuclear age, while in Hiroshima, it's put into the context of a collection addressing the atomic bomb and its effects.

In the 1990s, a member of the public published an article in the press, asking why Hiroshima was spending its money on sculptures that celebrated the beginning of the atom bomb project. There was a strange sense that this sculpture had developed a double identity, having two different lives in two different places, and two different names as well. Atom Piece's counterpart in Chicago is called Nuclear Energy.

Thinking about double identities put into play this idea of a masquerade—a kind of identity shift—I started to dive into the world of Noh theatre and the Japanese masquerade, and began collaborating with Yasuo Miichi, a Noh mask-maker, to create the series of masks which make up Project for a Masquerade. It's a proposition for a piece of theatre, probably an unrealisable piece of theatre, probably horrible if you tried to put it on stage! But it proposes a series of characters connected with the cold war and—in various different ways—to Henry Moore and the evolution of Atom Piece.

The traditional Noh play Eboshi-ori is about disguises, double identities, and trying to escape from your past. Seeing resonances with the story of Atom Piece, I populated Eboshi-ori with people who seemed to occupy roles between the play and the story of the sculpture, from Joseph Hirschorn to Anthony Blunt.

It was an extremely interesting and protracted working process, partly because I suppose the world of Noh theatre is quite entrenched, and set up to sustain tradition rather than innovate. It involved the long process of gaining the trust of Yasuo and finding a way to work with him. It was a great experience, and he was extremely generous in terms of what he brought to the design and realisation of the masks—it's incredible.

That was a first foray into Japanese culture in any formal way, which has led to a few subsequent things, including At Twilight, the play staged in Glasgow last summer. Like Project for a Masquerade, At Twilight generated a series of masks and costumes—but this time, it was actually realised onstage. It's a play about the poet W.B. Yeats, trying to navigate the modes and manners of Noh theatre back in 1916, when it was first becoming available as an art form in Europe.

AQMany of your works trace the movement of an idea or an object through the world. How do you know what to follow?

SSIt depends from context to context, from work to work. It tends to be fairly intuitive, in a way. You develop a nose for these things, a gut reaction which you follow—or don't. Very often you start something not really knowing where it's going to go, and what it might lead to. Which is part of the excitement, I suppose. Sometimes, I almost immediately have a very strong sense of what it is I want to realise, a strong visual image in my head of something, and the working process is a process of fleshing that image out, and giving it form and content. At other times, it's less defined.

For example, when I went to Toronto to visit The Power Plant [Contemporary Art Gallery], I took a trip to a commune on an island in Lake Ontario. On the ferry, there was a bicycle that had been dragged out of the lake. It was completely covered in zebra mussels'—it was an amazing object, a fantastic thing. That sparked this idea of working with, trying to collaborate with these mussels. I had read some story about how Henry Moore wandered the English seashore to pick up little pieces of flint that reminded him of bodies and bits of bodies. And suddenly that idea of throwing one of Henry Moore's bits of flint back into the water came to mind.

At times there's a sense that what I'm actually doing is looking for homes for ideas—these half-formed things that I carry around with me, which suddenly make sense in a particular context. They latch on to a specific set of parameters or circumstances—which grounds them, in a way.

AQProject for a Rift Valley Crossing was first exhibited at Nottingham Contemporary last year, appearing as a magnesium canoe and two almost empty tanks of highly saline water from the Dead Sea. But since then, you've completed the journey you outlined in that exhibition—fundamentally altering the work. How does your work change as it passes from one context to another?

SSOften, in those instances, it's a pragmatic consideration about when a work is ready to show. Many of these projects take years to realise, and I have on occasion shown things as they are progressing. It made a lot of sense to show Project for a Rift Valley Crossing as a proposition. In a way, all of the works exist as propositions in one sense. They are 'projects' in the true sense.

I was back with the canoe at the Dead Sea in November 2016, making a film which I'm now editing. And as I work on it, it's evolving into something else. Beyond documenting the journey we made, it extends the idea of being accountable for what we make and use. One of the things that we're doing at the moment is trying to put together a fantastically detailed set of credits which accounts for everything that is used to make the film. The canoe being the first of those, but then also the two cameras that we used to make the film—who made those, and who made the components that made those cameras, and so on and so on and so on. You end up with this extraordinary web of connections facilitating this rather simple piece of footage—of a rather simple gesture. The work is gathering its own speed and going in its own direction now.

AQIn Nanjing Particles (After Henry Ward, View of C.T. Sampson's Shoe Manufactory, with the Chinese Shoemakers in Working Costume, North Adams and Vicinity, circa 1875) (2008) and Silver Particle/Bronze (After Henry Moore) (2008), you're conducting an excavation into the molecular source of an event, rather than an expansion outwards. How do you approach ideas of scale?

SSI suppose that project conflates the macro with the micro, the geography of global production is understood in relation to the micro-geology of a photographic image.

AQDo you consider your work as having a political conviction? For example, in the Nottingham exhibition, there's the consideration of narratives of migration, of travel and journeys—all poignant themes given our current political climate.

SSFor sure, political concerns always circle the work. As soon as you start working in places like the Dead Sea, it's kind of impossible to avoid the political. The very nature of the place is so determined by what's going around it. Even on a physical level, the environmental changes that are happening in the Dead Sea are fundamentally driven by local politics, and water use, and control of land, and so on. It's palpable when you go there. And yet, my project never really began as an attempt to think about those things or deal with those things in a very direct way, I never set out to make a work about that situation, but it's very much there as a subtext.

My work is extremely simple in a way; it's almost an allegory, a little story about making a boat with some salt from the sea, and then using the boat to cross the sea that it came from. A super simple thing that has an almost child-like innocence to it. But then you realise that the greatest source of magnesium chloride in seawater is in the Dead Sea, and you're suddenly confronted with an outlandishly complex political situation within which to realise the work. It's a factor, you know, and an interesting one, too. But I always try and hold on to a sense of the work's autonomy within that situation. It's driven by its own logic, in spite of retaining the ability to talk to its context, and the tension between these factors drives the decisions behind how I end up showing the work. Part of this idea about creating this incredibly complex list of credits for the Project for a Rift Valley Crossing film is about finding how to tap into the complexity of the situation there.

Nanjing Particles was a work that was very much prompted by going to North America around 2008, when the United States was completely obsessed with China, and how 'they' were supposedly taking American jobs, and ruining American industry. It was a very current issue at that moment, and when I discovered this story of Chinese migrant workers coming to North Adams in the 19th century to make shoes—suddenly, that story had so much resonance. Again, that work exists within a set of political-economic parameters.

AQRelated to the question of migration, I'm thinking of your work Three White Desks (2008-9), in which there's a kind of visual translation. A desk was re-created from an image, and that was reproduced down the line. Is translation or transformation part of the underpinning logic of your work?

SSAbsolutely. I often use this word, slippage, which is related to translation in some way. A sense that every time you transpose something from one state into another, there's a kind of loss involved in that. But that loss has some, I suppose, creative energy—some potential as well as being a problem. The whole idea of mistranslation is quite exciting—that was one of the impetuses behind my interest in Yeats' investigation into Noh theatre as well. In 1916, he read a handful of Noh plays knowing very little about the culture in which they were written, and then wrote his own, which was a collage of what he understood to be a Noh play and a bit of Irish folklore.

While it was an act of complete, I suppose, barbaric mistranslation or misappropriation, it generated something new and interesting. That's an ongoing concern in a lot of the work: the problems and possibilities of that. The work has always been about these shifts, these transpositions, and translocations, and relocations. It's always there in various forms, often physical rather than language-based translation. But yes, I think it's becoming a more and more focussed theme, for sure.

AQI really like that word, 'slippage', it makes sense throughout your entire body of work: the generative potential of where these things don't quite meet up. I have one last question for you, it's kind of a silly one, so bear with me. But I was thinking about how so many of these narratives, or a word that you've used a lot today is 'logic', hinges on the discovery of one thing that leads to a discovery of another, and I was wondering if you think of that as being particularly related to a more unexplainable thing—to fate?

SSI almost use the word 'logical' sort of ironically I think! You can call it logic, but it's largely quite illogical or if it is logical it's a kind of skewed sort of logic. I'm a huge fan of serendipity. That's absolutely a driving force for the work.

I've occasionally talked about how it sometimes feels that the work has its own engine, and it's not me that's driving it. I know that sounds a little crazy, but there is that sense that what you're doing as an artist is trying to hold everything on the rails, and yet somehow the thing is moving, whether you like it or not. A sense of one thing becoming another, and one invitation leading to another, and one discovery leading to another—it does seem like it's a little out of my control at times, which I love, actually. It makes life quite exciting. Maybe it's disingenuous to talk like that, but there is an element of that. What I'm doing is trying to let those serendipitous events lead me—to not suppress them, but to let them have a place in the work as much as possible. —[O]