Ruth Asawa Revisited through Drawing

Exhibition view: Ruth Asawa, Through Line, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (16 September 2023–15 January 2024). Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo: Filip Wolak.

A major exhibition at the Whitney in New York is the first institutional show to focus on Ruth Asawa's drawings, providing insights into her lifelong commitment to the art form.

When Asawa died ten years ago, she was mostly forgotten outside of California. Over the last decade, however, the art world has turned its attention to the Japanese-American artist, and following several belated museum showings and books about her work and global gallery David Zwirner announcing representation of her estate in 2017, she is now a relatively well-known name, her delicate wire sculptural works instantly recognisable to many.

Most recently, the Whitney Museum of American Art opened Through Line (16 September 2023–15 January 2024), an ambitious showing of Asawa's drawings which heralds the first time a major institution has focused so extensively on Asawa's non-sculptural work, with over 100 drawings, graphic works, and watercolours from public and private collections. Many of the works have never previously been exhibited, and they display the great range of her drawing skills, allowing for a broader understanding of her practice and her approach to art making.

By centring on her graphic works, the exhibition turns its attention from Asawa's well-known wire sculptures to place drawing at the heart of her practice. As Asawa said in one of her late interviews: 'Working in wire was an outgrowth of my interest in drawing.' The exhibition signals a remarkable shift in the estimation of the medium's importance; Asawa herself was turned down by museums and galleries—de Young in San Francisco, Peridot Gallery in New York—when she requested her drawings and graphic works to be shown instead of her sculptures.

In the Whitney's engrossing exhibition, curated by Kim Conaty and Edouard Kopp, the artist's works are organised thematically to emphasise eight recurring ideas and patterns in over five decades of work. The stated eight themes are poetic rather than specific to any technique or style, including 'Learning to See', 'Rhythms and Waves', and 'Forms Within Forms'.

Conaty, the Whitney's curator of drawings and prints, has prepared for this exhibition since she joined the museum in 2017. She explains in a recent interview that Asawa viewed her drawings as the most consistent activity in her life as an artist, 'an important force, the sculpture clearly coming from it, wire the equivalent of line'. Asawa worked on her drawings daily, in an intimate ritual that sustained a form of physical labour she was familiar with from her early childhood.

In [Asawa's] meticulous drawings and graphic works, you can see and feel the labour going into each line.

Ruth Asawa was the daughter of Japanese immigrants, poor farmers in California's harsh inland, who were legally restricted from owning land in the U.S. as Japanese residents. As a child, she toiled in the fields, working with her hands, learning skills and a meditative approach to repetitive work that would return as a theme in her later drawings and sculptures.

In 1942, Asawa and her family were incarcerated in the World War II-era internment camps for Japanese Americans. Initially, the artist, with her mother and five siblings, was sent to live in a horse stable at the Santa Anita racetracks, a detention camp in Southern California, in what is now—with the perfect irony of American history—a middle-class suburb named Arcadia, home to one of the largest Asian-American communities in North America.

Asawa did not see her father or sister for several years. But the internment camp gave her the chance to improve her drawing and painting skills, learning from fellow incarcerated Japanese-American Disney animators. They taught her to use crafts and art as a way of finding meaning in daily life. Asawa also observed other interns who were tasked with making camouflage nets for the American military, with delicate threads in different colours, a skill that was mirrored in her wire sculptures many years later.

Following her release, Asawa studied art at Milwaukee State Teachers College in Wisconsin (now University of Milwaukee-Wisconsin), intending to teach. However, she was unable to obtain her licence, as no school district would offer her a placement as a Japanese-American.

Instead, Asawa went to Black Mountain College in North Carolina, now a legendary breeding ground for the postwar American avantgarde (among faculty and students were composer and theorist John Cage, dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, and artists Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Dorothea Rockburne, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly). Her teachers were Josef Albers and architect Buckminster Fuller, who became lifelong friends.

In the early 1950s, Asawa held seminal exhibitions at Peridot Gallery in New York, alongside Constantin Brancusi and Louise Bourgeois. But her delicate sculptures were often damaged when they were sent back to California, and she eventually stopped exhibiting on the East Coast. She focused rather on California, where she also devoted much of her time to art education and public artworks.

Many individual artists and gallerists can be credited with bringing Asawa back into the spotlight—not least Albers—but Asawa's belated stardom has been mostly driven by a wider political and aesthetic shift in American contemporary art that elevated previously ignored voices, particularly those of women and ethnic minorities.

It's telling that many of America's great women modernists and abstract artists only received individual biographies in the past decade, including Joan Mitchell (2011), Lee Krasner (2012), and Agnes Martin (2015). Asawa had to wait until 2020. At the Whitney, I couldn't help but ponder how rare it is, even with the revised, more progressive, more inclusive canon of contemporary art, to see works from someone of her socioeconomic background in these institutions.

Poet Cathy Park Hong has spoken of Asawa's art as a reflection of the enormous, invisible work of Asian migrants in the American West in the early 20th century. California's vast agricultural areas now account for nearly half of all fruits and vegetables consumed in the United States, and so much of that infinite farmland was first ploughed by Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino migrants.

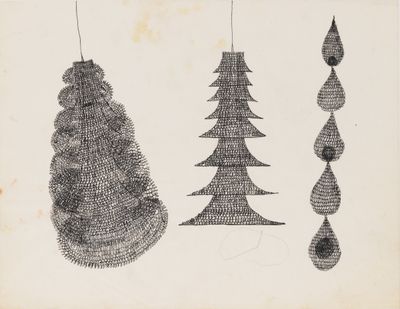

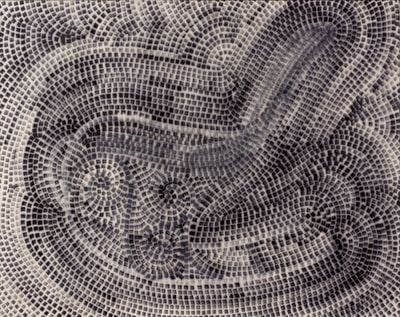

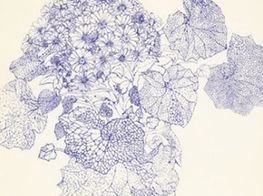

Asawa often spoke of the connection between agriculture and craft and Albers' lessons about learning to love the process itself. In her meticulous drawings and graphic works, you can see and feel the labour going into each line. Take her 1960s felt-tip drawings, made using modified pens with split tips to emulate the soft rhythms of the ocean, for example Bentwood Rocker (MI.176) (c. 1959–1963). Other works reflect her lifelong interest in calligraphy, which she learned early in life at a Japanese weekend school in California.

The recent biography on Asawa by Marilyn Chase refers to the artist's own characterisation of herself as a 'citizen of the universe', but when I visited the show at the Whitney, I thought about how geographically specific much of her art is and how Californian it feels. The palette often seems to be drawn from the dry, chronic late-summer light that shines over the valleys east of the San Francisco Bay.

In Asawa's meticulous recreations of Sacramento Delta leaves or beached fish from the Pacific coast, there is a love for the world's physicality that reminds me of a later, still-active Californian artist, Vija Celmins. They both seem to search for something almost sacred in the working process itself, in the patience and care with which they recreate the relatively banal objects around us.

I linger in front of a few mesmerising works I had never seen before: paper sculptures. In her work, Asawa usually avoided referencing her years in the internment camps, but these sculptures, so full of sensuality and freedom, stand out as such an obvious contrast to the very idea of confinement. They refuse to be still or remain in any particular space or shape. Instead, they pulse softly and gracefully, like sea anemones or a hummingbird's wings, in slow motion. —[O]

![Untitled (P.002-I Tied-Wire Sculpture Drawing with Five-Pointed Center Star, Embossed [Silver]) by Ruth Asawa contemporary artwork works on paper, mixed media](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/29/29b0c3ad-9578-4ea3-88ff-e1555af2202a_200_201.jpg)