5th Mardin Biennial Confronts Dispossession at an Ancient Crossroads

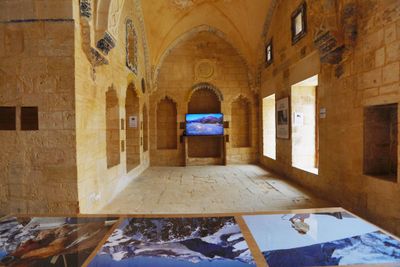

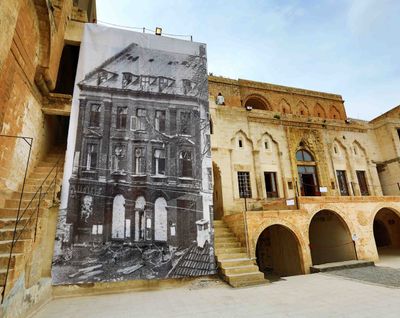

E.B. Itso, Allotria, Mardin #1 (2022). Print on fabric. Variable dimensions. Exhibition view: 5th Mardin Biennial, The Promise of Grass, German Headquarters, Mardin (20 May–20 June 2022). Courtesy Mardin Biennial.

In Turkey's south-eastern city of Mardin, the broad terrace of a grand 19th-century yellow limestone mansion overlooks what locals call 'the sea': a vast, shimmering Mesopotamian plain extending across the Syrian border, some 30 kilometres to the south.

Inside one of the cool, vaulted rooms of the stately building, artist Sibel Horada's mixed-media installation Shaped by Water (2022) gathered pieces of coloured styrofoam washed ashore along the Marmara and Black Sea coasts, near her home city Istanbul, crafted into totemic sculptures.

In another chamber, bronze symbols were half-buried in dust, emerging from or returning to earth in Lara Ögel's In the Hour of Terra (2022). Outside, the mansion's façade was partially cloaked in E.B. Itso's monochrome print on fabric, Allotria, Mardin #1 (2022)—a life-size depiction of a Copenhagen apartment occupied by squatters during the 1980s.

Themes of transformation and resistance ran through the 5th edition of the Mardin Biennial in Turkey (20 May–20 June 2022), organised under the title The Promise of Grass. For the occasion, New Delhi-based curator Adwait Singh brought together 40 artists representing two dozen countries in this ancient silk road city.

Taking grass as a metaphor for life regenerating within inhospitable conditions, Singh's curatorial promise was to re-envision dispossession as an opportunity to create 'new models of sovereignty and co-existence'.

The event also marked another rebirth for the Biennial, which had weathered many setbacks during its short history. Initiated in 2010, the Mardin Biennial saw its 3rd edition postponed after I.S.I.S. fighters attacked the Syrian border city of Kobane.

While plans to hold the Biennial in 2020 were thwarted by the global Covid-19 pandemic, leaving the 5th edition to take place amid a major ongoing domestic economic crisis.

Singh's curatorial promise was to re-envision dispossession as an opportunity to create 'new models of sovereignty and co-existence'.

Against this heavy backdrop, the Biennial's mysticism-infused probing of 'histories, cosmologies, futurisms, experiments, and songs of the dispossessed' felt both heartening and, at times, weightless, as if circling the subject without landing.

Intriguing but fanciful, two video works—Jonas Staal's 94 Million Years of Collectivism (2022) and Uriel Orlow's Dedication (2021)—explored the ecological basis for more cooperative ways of living through relationships between Precambrian organisms within the plant kingdom.

While fascinating to consider how plant-like animals of the Ediacaran Period existed in symbiosis half-a-billion years ago (the subject of Staal's work), or how fungi and root systems help trees intercommunicate (in Orlow's installation), it's a big leap to consider these to be alternative 'models' for rather more complex human societies.

More impactful were works documenting, responding, or initiating acts of resistance against repressive power structures. Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam's Drapchi Elegy (2017) pairs footage of the daily life of a Tibetan nun, who was a 1990s political prisoner, with multilingual banners of lyrics to protest songs she and her companions secretly recorded in jail.

Karan Shrestha's dreamy double exposures of Indigenous children from Nepal (we exist; part of his installation stealing earth, 2018–ongoing), demand recognition for their subjects, rendered stateless by discriminatory laws, while honouring their communities' relationship with forest ecosystems—ties that have been severed under modern conservation policies.

Helsinki-based artist Sasha Huber collaborated with an Inuit throat-singing duo to symbolically exorcise the name of an ancient glacial lake in Canada from its legacy of racism for her video work Mother Throat (2017–2019).

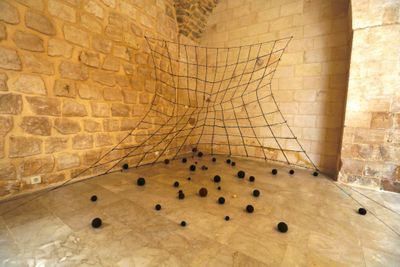

Kurdish artist Fatoş İrwen collected hair from female political prisoners while behind bars in Diyarbakır, around 90 kilometres from Mardin, and braided it into ropes to make Safety Net (Safety Net for Women) (2017–2020). The installation hung in a corner like a spider web, alluding to captivity; here, equally a source of collective strength.

Likewise, Nejbir Erkol's delicate pencil drawings (various titles, 2020–2022) quietly spoke to the violence and resilience in the region. These depict canary grasses the Kurdish artist collected from a pit created by a mortar shell landing near her family home in Nusaybin, a city in the Mardin province facing the Syrian border.

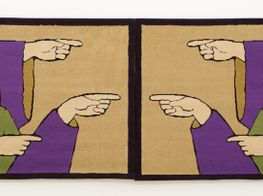

Gülsün Karamustafa's two textile collages, Four Panthers, Two Praying Carpets, One Jesus, Baby Violinist, Stars and Tulles, and Melancholic Basilisk (both 1980–2022) allude to the violence in south-east Turkey, which drove thousands from the region in the 1980s and 90s, and how this mass internal migration transformed Istanbul and other large cities in the Western part of the country.

The artist sewed together colourful fabrics she had gathered during that period—leopard print, gold lamé, silky quilts—to frame images of Jesus and a 1950s-style pin-up re-imagined as the mythical snake-woman Shahmaran, creating a kind of hybrid kitsch iconography.

One question thus remains: to whom does cultural heritage belong?

An unintended reminder of the fraught and often repressive political situation in the region and beyond came during the Biennial's opening weekend when heavily armed security forces watched over a local festival featuring a bake sale, live music, and group dancing.

The ways states use surveillance as a tool of dispossession and control were referenced in two Biennial pieces by Turkish artist Merve Ünsal. Her audio recording Into the Wind (2022), installed in a small courtyard, behind the twisting trunk of a fig tree, whispered intercepted communications from all-seeing, yet fallible eyes in the skies.

A few words to drones (2022), a large digital print on tarpaulin hung over another courtyard space sending a message skyward: 'Metal and plastic have been fatigued'—as if the materials themselves are becoming resistant to how they are used.

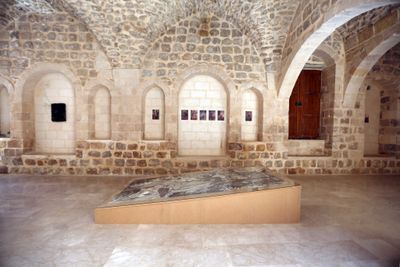

Besides a few standalone pieces like Ünsal's, most works in the Biennial were displayed in 19th-century stone buildings characteristic of the architectural style that gives Mardin's old city its cohesive look.

One, dubbed the 'German Headquarters', has a tragic history that ties in deeply with the Biennial's themes of dispossession, but cannot be found in the event's written materials, beyond a brief mention of its original name and a short description of its history as military headquarters.

It has been said that Iskender Atamyan, the Armenian owner of the Iskender Atamyan Mansion was among the first to be deported from Mardin during World War I, leading to the 1915 genocide, leaving his home to be requisitioned by the German military.

But since the Biennial's inauguration, the sanitised version of Mardin's multicultural and multireligious past remains a big selling point for the booming and mostly local tourism.

Today, the atmospheric old town where the Biennial is held is filling up with hotels, restaurants, and shops as real estate prices soar and Mardinites move to cookie-cutter apartment blocks in new settlements and nearby towns.

One question thus remains: to whom does cultural heritage belong? This question was grappled with most pointedly in parallel exhibitions by three local artists, rather than the Biennial itself.

Sounds of perpetual construction on Mardin's rooftops echo through scenes of selfie-taking visitors in Hüseyin Aksoy's video The past has hard reminders and memories, but the future also has hope (2022). While his earth-toned painting A review on Mesopotamian houses (2022) strips the cityscape of its context and inhabitants, as if a theatrical backdrop.

Staged during the Biennial's opening weekend, Ateş Alpar's performance Looking at the Ruins (2022) saw the artist silently walking the streets carrying the replica of a sign that once welcomed visitors (in Turkish, Kurdish, English, and Arabic) to the historic south-eastern town of Hasankeyf—before it was submerged under water following the construction of a controversial dam.

Another set of ruins, those of the ancient Roman city of Dara, lie on the plain just south of Mardin. Some of these structures appeared in artist Mehmet Ali Boran's series of small watercolours, 'Episode Stories' (2021), but the works' real focus is not on Dara as an archaeological site, but a living place, with the troubles that entails.

One painting depicts a bag of wild mushrooms traditionally collected by locals but gone scarce in recent years due to ecological changes; another, a street vendor selling stuffed mussels in Istanbul—a profession dominated by young men from Dara who have had to leave home to find work, joining the ranks of the global dispossessed. —[O]