Entgrenzungen [Dissolving Boundaries]

jakob bill's Bisections

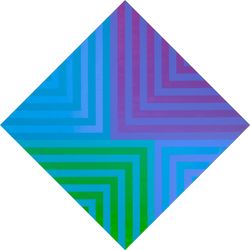

It's actually very simple: the works by jakob bill presented in this show can be described in just a few words: square pictures, hung at an angle as if they were diamond shaped, evenly covered by stripes a few centimetres wide and centred along a horizontal or vertical line. But as is often the case with constructivist and concrete art, bill's paintings are not limited to what can be measured and described in words. It would not be doing them justice to describe them only in terms of their material state and thus, the "factual facts", as Josef Albers1 put it. Rather, they can really only be grasped when their optical effect — the 'actual facts' — are properly appreciated.

The boundaries of paintings

Even the format is remarkable: the diamond shape bill has chosen for his bisections is based on the square, a central, symmetrical form that one of the fathers of abstract painting, the Russian suprematist Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935), considered the nucleus for all of the development of form in geometrical abstract art.2 While the square, with its four symmetrical lines parallel to the edges and diagonals, is always linked to the vertical/horizontal frame of reference and thus remains 'earthbound', the diamond shape, like the circle, looks like a form without direction and hierarchy, detached from earth's gravity. The form's connection to the frame of reference is at least loosened by the fact that, although the diagonals remain a part of it, all of the other ones — meaning, the majority of lines comprising this shape — are detached from it.3

The format also affects more than just the relationship of the picture to the space: thanks to the unusual hanging, which runs counter to the horizontals and the verticals in the space, the diamond-shaped painting is seen as an object, while the lack of a conventional frame also contributes to this impression. Comparable to Frank Stella's shaped canvases from the early 1960s, the diamond-shaped picture hangs in front of the wall, raising awareness of the image's surface and emphasizing its autonomy. Thus, even the choice of format points to something outside the image and becomes a reflection on the relationships among the picture, the wall, and real space.

Surface boundaries

The artist's horizontal and vertical lines seem to be the only fixed things in this floating object. Vertical or horizontal, light and dark stripes stand out sharply from each other, while vertical and horizontal lines clearly divide the two halves.

Yet, under the gaze, what at first appears to be a rigid pattern begins to move: first, the vertical or horizontal division of the two halves hardly ever leads precisely from one corner to the opposite one; rather, it begins at a slightly offset point and travels the same distance to arrive at the opposite corner on the other side. The division made across a stepped line sets the whole structure in motion. The balanced form appears asymmetrical for a moment, only to come to rest again in the next. Sometimes, the stepped division creates frames within the image itself, which enclose a tiny rectangular form, the most minimal element of the image, turning the painting itself into a frame and once again linking the square image to the real space of the presentational surface, the wall.

Finally, the alternating light and dark vertical and horizontal bands open up endless interplay between figure and ground, further intensified by the shift of colour patterns between the two halves of the painting.

Boundaries of perception

The most consequential compositional step in bill's process of bisecting his pictures, however, is the use of colour. Unlike his predecessors in constructivist and concrete art — who wanted to set themselves apart from fauvist and expressionist peinture, as well the figurative and the abstract, by painting without any discernible individual signature — bill allows himself to use a painterly approach to colour. For instance, he has been working since the 1960s with pastel hues and bright colours, which move toward each other within the continuum of the picture, then seem to merge, thus dissolving the strict form. While the works from the early 1970s already feature colour schemes inside of square grids, bill has been creating finely nuanced colour gradations since the late 1970s. These chromatic, barely perceptible gradations divide surfaces on the one hand, but where they come close to each other in the intensity of their hues, they also connect them. Since the eye is not at all capable of perceiving the individual gradations of these subtle nuances, a vibration sets in; the surfaces seem to tremble and flicker, and once again the strict forms are dissolved. Moreover, the shimmer points out to light as a constantly changing phenomenon in real space.

As Max Imdahl has shown, this kind of emphasis on colour, as opposed to line, raises an awareness of sight; through this develops a distinction between the conceptually determined identity of an object and actual visual experience:

What really counts is not the visual affirmation of the a priori certainty of an object, but rather, the innovation of something seen a posteriori within a deliberately created, exceptional state of seeing colour. [In this way, the image causes the viewer] to perform a productive act of reception. By virtue of its colours, the painting becomes an experience under the gaze — one could speak of an aesthetic process of seeing and no longer simply of the aesthetics of the object, which concern the facts of the painting itself.4

It is the great achievement of concrete painting like jakob bill's to make out of a simple, straightforward, rigid structure a celebration of sight.

© 2022 Heinz Stahlhut

1 Gottfried Boehm: Was heisst: Interpretation? Anmerkungen zur Rekonstruktion eines Problems, in: Kunstgeschichte - aber wie?, hrsg. von der Fachschaft Kunstgeschichte München, Berlin 1989, S. 7-13, S. 13

2 Helga Behn: Suprematismus, in: Kasimir Malewitsch. Werk und Wirkung, hrsg. von Evelyn Weiss, Ausst.Kat. Museum Ludwig, Köln 1995, Köln: DuMont Buchverlag, 1995, S. 127.

3 Rudolf Arnheim: Die Macht der Mitte. Eine Kompositionslehre für die bildende Kunst, Köln: DuMont Buchverlag, 1983, S. 123f. und 143f.

4Max Imdahl: Farbe. Kunsttheoretische Reflexionen in Frankreich. München: Fink, 1987, S. 16.

© 2022 Heinz Stahlhut

Rosenberghöhe 4

Lucerne, 6004

Switzerland

www.galerieursmeile.com

+41 414 203 318

+41 414 202 169 (Fax)

Tues - Fri, 10am - 6pm

Sat by appointment