One of the world's best known 20th century photographers, Don McCullin has shot some of the most recognisable photographs in history throughout his 50-year career. His most famous image is perhaps Shell Shocked Marine, Hue, Vietnam (1968), in which the titular soldier stares, eyes glazed, somewhere just beyond the camera. Having grown up in North London during the Nazi bombing of England, McCullin would go on to shoot poignant images of conflicts in locales including Lebanon, Iran, Afghanistan, Uganda, Biafra, Vietnam and Cambodia. In the course of his photographic career, McCullin has found himself in some of the world's most dangerous conflict zones: in 1968 in Cambodia, his camera stopped a bullet that was meant for him; he also had a bounty on his head in Lebanon and was imprisoned in dictator Idi Amin's Uganda for four days. As well as his war photography, McCullin is known for his sensitive photos of his Somerset home and his insightful recordings of working-class life in and around London.

Read MoreMcCullin got his start when he submitted photographs he had taken of the Guv'nors (a London gang) to the Observer. The Guv'nors in their Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park, London (1958) was one of McCullin's first published images, showing a group of the young boys hanging out inside a gutted and abandoned building. Images of industrialised Britain's working class would continue to hold an important place in his practice throughout his life. Later images of this theme became more atmospheric, exemplified in A man walking towards his work at the Steel Foundry (1963), where a lone figure walks through a decrepit landscape towards dramatically billowing smokestacks. Boys boxing (c. 1960s), on the other hand, shows two youths fighting on the street in the distance, but the image of the pair is foregrounded by a pile of trash in the gutter. Such images show the intimate and dangerous relationship between industrialisation and the vulnerable populations used to fuel it.

McCullin's first major assignment was the war in Cyprus in 1964, for which he won a World Press Photo Award. However, his photos of the Vietnam War are perhaps his best known. On a hill in Da Nang a priest hears soldiers' confessions (1969) exemplifies McCullin's skilful depiction of the atmosphere of war; in the image, a soldier kneels as a priest sitting on a metal chair leans over and blesses him. Three other soldiers wait a respectful distance behind. Beyond them, smoke swirls ominously, as if the soldiers are waiting to ask forgiveness for a crime they have just committed. In another startling image of war—this time in Beirut—titled A Palestinian Woman Returning to the Ruins of her House, Sabra, Beirut (1982), a woman stands stricken with grief inside what is left of her home. Though these photographs successfully elicit a strong emotional reaction from the viewer, throughout his career McCullin has maintained that he does not perceive his photographs as artful, and he does not consider himself an artist. Rather, he sees his photographs as a mode of communication.

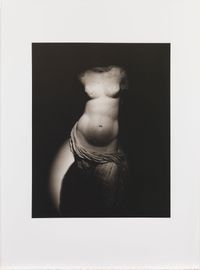

Though the public will best recognise McCullin for his field work in locations of crisis, from the early 1980s he decided to find a voice for himself outside of war. During this period, he turned to landscapes and still-lifes around his home for subject matter. In one work from the early 1980s, titled Flowers & Fruits, early attempts at still life, photographed at my home in Somerset, we see a much more peaceful aspect of the photographer's oeuvre: flowers and fruits sit quietly side by side, delicately framed by a textured wall. This body of work stands in stark contrast to his standard subject matter, but his skilful eye for composition and effective command of highlights and shadows remains ever-present.

McCullin was the first photojournalist awarded a CBE (1993). In 2016, he released a limited edition three-volume box-set publication titled Irreconcilable Truths, spanning his life's work.

Casey Carsel | Ocula | 2018