Liquid Ground at Para Site Seeks a Future Commons

Yi Xin Tong, The Birth of Julung-julung: The Aquatic Dragon (2019–2020). HD video with sound. 24 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist and Vanguard Gallery.

In Hong Kong, Para Site presents a proposal for a future commons in Liquid Ground (14 August–14 November 2021), a group show that brings together works by 15 artists from across the world to explore the environmental impact of land reclamation.

Organised in collaboration with UCCA, this co-commissioned exhibition is the sixth iteration of Para Site's open call to emerging curators. Alvin Li and Junyuan Feng were invited to execute their plan to clap back at the much-disputed Lantau Tomorrow Vision project in Hong Kong.

The controversial infrastructure project proposed by Hong Kong's Chief Executive Carrie Lam aims to reclaim 1,700 hectares from the sea and turn Lantau Island, one of the city's untouched natural reserves, into an 'economic hub' for commercial and residential business.

As many island and coastal states in Asia face the same dilemma of land scarcity, newly commissioned works and large-scale installations by artists including Future Host, Ho Rui An, Jessika Khazrik, Heidi Lau, Lee Kai Chung, Leelee Chan, and Riar Rizaldi speculate on how to preserve historical ecologies and maintain a connection to earth amid urbanisation.

Shifting between liquids, solids, and spiritual connections, Yi Xin Tong's video installation The Birth of Julung-julung: The Aquatic Dragon (2019–2020) is positioned in the centre of the exhibition space.

Structured like a travelogue, the video follows the artist as he travels to Dinawan Island in Malaysia, and in his reflections a personal link with land and water grows. The story ends on the small island, with Tong gifting a lucky water dragon charm to the local fishermen.

The water dragon is believed to restore equilibrium between humanity and nature. But in this work, it also functions as a link between then and now: a symbol of the enduring cultural significance of folk tales as a means to honour the past and remember the place that the natural world had within it.

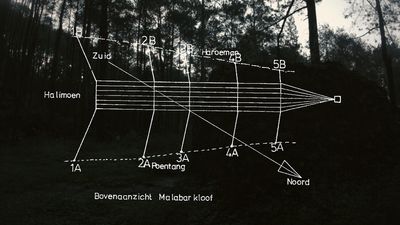

In a similar vein, Riar Rizaldi's video Tellurian Drama (2020), positioned on an adjacent platform to Tong's piece, builds on an indigenous and spiritual connection to land that was once colonised.

The work focuses on the legacy of Radio Malabar, a station set up in West Java in 1923 by the Dutch East Indies government, which has been reactivated as a historical site by the Indonesian government in the present.1

Hazy imagery of indigenous dancers in mountain fields express the meaning of geotechnologies for the indigenous people of the area, while overlays of scientific maps and sepia-toned radio station stills from the twenties set forth the problem—not to mention the colonial roots—of urban development that prioritises infrastructure over the needs of the community.

'In the land where Radio Malabar was built, mountains are a media technology', spoken word echoes in the video. 'Their cosmology believes that their ability to communicate with the mountain and accumulated ancestral energy is the method to engineer the earth.'

Amid spoken word, the video's soundtrack is composed of a vocal embodiment of the mountain where Radio Malabar was built: a composition of eerie murmurs from synthesised insects and birds and field recordings, with an end sequence of an Indonesian man playing the zither and singing on the steps of a station.

The theme of nature and myth continues in The Fountain (2021), a sculpture by Heidi Lau that is a part of a collaboration with Future Host. A clay sculpture forms an abstract ceramic piece that invokes a primordial organism born from a river.

This seemingly fossilised creature is manifested in tandem with a two-screen video that is projected onto a corner of white wall, Worlding Hands (2021). Known in Chinese mythology, the main character portrayed is Nuwa, the mother goddess thought to have created humanity with her bare hands.

Tapping into the idea of natural materials constantly shifting between states—whether liquids, solids, or spirit—Nuwa appears in the video as a muddied and naked woman, while a yellow serpent moving through clay in untamed nature reflects the symbolic form she can take in folklore.

Liquid Ground is an indictment on the large-scale redevelopment projects from Hong Kong to Lebanon that leave the natural world out of the equation.

Taking over most of the empty gallery floor is Jessika Khazrik's imposing structure Klub Interments (2021), a newly commissioned multimedia installation. A three-step stairwell on a trapezoidal platform protruding from the wall consists of a light and sound display, with viewers invited to step onto the podium to experience pulsating vibrations meant to recreate the drum of a dancefloor.

Klub Interments is dedicated to the Normandy Landfill in Lebanon, a now transformed waterfront known as L'Avenue des Français. It was a dumping ground for the city's garbage and military refuse from 1976 to 1994, and as the curators state in the exhibition brochure '[the] fallen architecture was ironically turned into a commercial club area from which methane gases still secretly fume.'

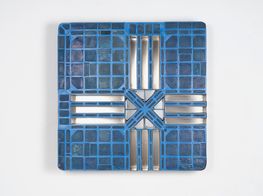

Attempts to tackle themes of developmentalism connects Khazrik's work with Lee Kai Chung's Sea-sand Home (2021). Commissioned for this exhibition, the installation of three metal silos towers in the Para Site space. From them, replications of sewage pipes stick out, with mountains of salt sprawling from below.

Sea-sand Home portrays the process of sand being turned into construction material, a common process across the world. Paradoxically, though, salt is the natural enemy to modern infrastructure, with coastal cities facing a constant push and pull with the ocean and its effects.

The paradox of salt is present, too, in the process of land reclamation, which utilises sand to encroach into the water, just as the threat of rising sea levels seem poised to destroy these artificial extensions, all the same.

All of which brings us back to Lantau, and the government plans that threatens its ecosystem. Zheng Bo offers a microscopic depiction of Lantau's island ecology in Drawing Life (Xin Chou, Grain Rain) (2021). A low-lying table hosts the artist's drawings on paper, which are displayed in an orderly grid.

Zheng Bo's simple portrayal of flowers, leaves, and plants are a gentle reminder of the natural diversity of the city's wildlife that quietly exists but is often overlooked—a point that returns to the premise of this exhibition. 'We tend to pay more attention to the human drama than the material backdrop that underpins everything and is no less dynamic and undulating,' the curators point out.

This oversight comes through in the film Cruel Story of Youth (1960) by Nagisa Oshima, set against the backdrop of a brutalist post-war Japanese coastline. An orderly society is viewed from the outside before 'two lovers against the world' draw viewers into a tumultuous context, as they slowly uncover the harsh realities of a rapidly industrialising society.

Framed by scenes taken from the 1960 May Day demonstration in Tokyo, Cruel Story of Youth presents a familiar fight for freedom and power that runs through the modern histories of the world. But amid this human drama, the waters off Japan's coast, which have often served as a reminder of nature's ability to destroy whatever man makes, are never far away.

Through this lens of simmering survival and existence, Liquid Ground is an indictment on the large-scale redevelopment projects from Hong Kong to Lebanon that leave the natural world out of the equation.

What follows is a contextualisation of the Lantau Tomorrow Vision project in Hong Kong as an open threat—indeed infringement—on the ecological and cultural significance of a natural environment that, as this exhibition shows, forms part of the community with which humans live. —[O]