Eisa Jocson Explodes the Frame

In Partnership with Tai Kwun Contemporary

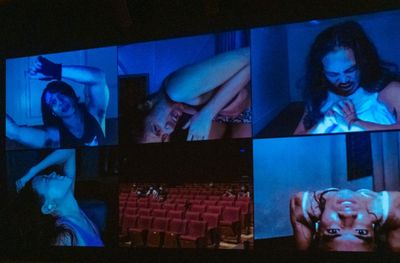

Eisa Jocson, Host (2015). Courtesy the artist and Tanzhaus-nrw, Düsseldorf. Photo: Andreas Endermann.

Eisa Jocson, Host (2015). Courtesy the artist and Tanzhaus-nrw, Düsseldorf. Photo: Andreas Endermann.

Eisa Jocson is a renowned choreographer, dancer, and visual artist who has long been interested in the politics of the Philippine body, particularly with regards to questions of representation and visibility.

The winner of the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award in 2019, Jocson's artistic practice has looked into how the body moves—physically and across borders—and the conditions under which it moves; conditions that are transected by social, economic, class, and other conventions, often through the prism of the service and entertainment industry.

For the 'Happyland' series (2017–ongoing), a research project exploring migrant labour and happiness production, Jocson has delved into techniques of dancing—from pole dancing to 'macho dancing'—as well as into the affectations of the character of a Disney princess. In the process, she has become critically fascinated by the highly skilled Filipino performers employed by theme parks to play the role of animal characters, which led to a study on the conditions and behaviours of displaced and captured animals in zoos.

Zoo is the third iteration of the 'Happyland' series, and furthers Jocson's research. Commissioned by Tai Kwun Contemporary and presented in the recent exhibition My Body Holds Its Shape (25 May–27 September 2020), Zoo initially set out to explore the relations between humans and animals, systems of labour and confinement, as well as the politics of the gaze and spectacle, linking the bodily practices of humans playing animal characters in theme parks with the conditions of displacement and capture faced by animals in zoos.

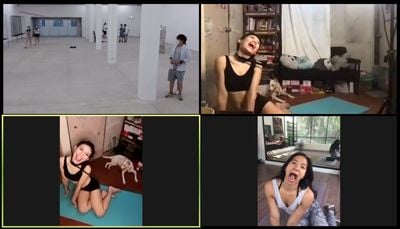

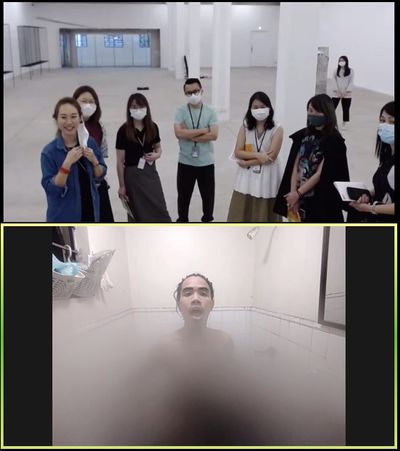

Jocson and her Filipino collaborators were meant to take part in a durational performance throughout the run of the exhibition at Tai Kwun. With the upheaval caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and its attendant travel restrictions and closures, however, this became impossible. The work was transformed as a result—displaced as an online performance transmitted into the exhibition by livestream from Manila, along with live performances by Hong Kong-based performers staged in the gallery. The issues of representation, spectacle, and confinement suddenly took on an even greater level of mediatisation, touching on themes of digital participation and surveillance.

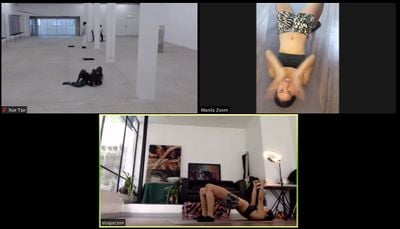

Towards the end of the exhibition, Zoo entered into a new phase of development. The work was adjusted accordingly to the new Covid-19 regulations imposed by the Hong Kong government, with no live performance allowed. The Hong Kong dancers performed behind the glass between Thea Djordjadze's sculpture .pullherawaypull. (2020) and the building's façade—a narrow alleyway outside the 'official' exhibition space. The perspective of their performance became flattened, almost like an aquarium screen—a 'surface' that was mirrored by the livestream monitor.

In this conversation, which took place in August 2020, Xue Tan, the curator of My Body Holds Its Shape, talks to the artist about the origins, process, and unexpected twists and turns in the making of Zoo.

XTEisa, how are you? Could you tell us where you are at this moment and how things are around you and in Manila?

EJI'm okay. I'm in Manila with my family. Manila is currently in MECQ, which stands for Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine. In short, it's a lockdown. To give you an idea, I'm going to state some facts that I've researched today. Today, on 15 August, a further 4,351 new Covid-19 cases have been confirmed in the Philippines, and a new record of deaths—159 in a day. It's the highest I've seen so far. To give you a bit of context on where the Philippine government is with the fight against Covid-19, 200 billion pesos of aid has been allotted.

One news article describes it as 'mula ulo hanggang paa' corruption—corruption from head to toe. Like with a lot of governments now, state violence is the new normal—on all levels of society. There's opportunism around the pandemic. And the troll army on social media is working hard to continually dominate and shape the popular narrative.

XTWe are facing the third wave of infections in Hong Kong; as you know, My Body Holds Its Shape has been closed for almost one month now. I feel like Zoo, which is part of the show, has had several lives—and imaginary lives.

Originally, the work was planned to be performed by you and your collaborators in the exhibition space, which was scheduled to open on 13 March. When Covid-19 hit Hong Kong and other Asian countries at the beginning of February, your quarantine experience lasted almost four months, with a very severe situation in Metro Manila.

EJYes, and now it's been about five months of quarantine.

XTCould you share with us the process of realising physical and emotional anxiety and stress as materials for the work that you have been developing? How do you link that to the animals in captivity that you were looking at before the pandemic?

EJIdeally the exhibition was going to provide the Zoo team in Manila the opportunity to do performance research, which would allow us to gain a sense of the durational performativity similar to the condition of a zoo. An exhibition and a zoo share the same purpose, which is for the audience to look at something—whether it is an object, a person, a performer, or an installation.

With tours and projects being cancelled or postponed, it quickly became apparent that we were going to have to rethink the project and adapt it to pandemic conditions.

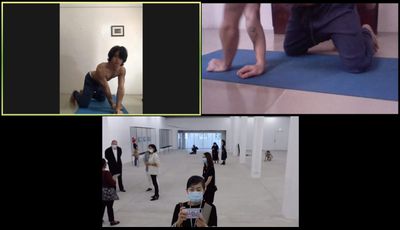

Before the pandemic, we were already looking at stereotypical behaviour of animals in captivity. They do this repetitive behaviour as a sign of psychosis and possibly to cope with the fact that they are in a limited space. It made perfect sense to adapt and continue performing the Zoo project in Hong Kong as a livestream from our very own private enclosures in Manila during the lockdown, as it speaks to the layers of systemic confinement and separation that we are experiencing at the moment.

In a way, we now have a glimpse of how animals experience captivity. It's definitely very far from an animal's experience, but with the sense of the lockdown being drawn out, almost unending—this uncertainty is what is driving people crazy right now.

Exercise has been an important part of maintaining one's health and sanity through quarantine. This repetitive activity reminds me of hamsters running on a wheel, and the similarity between the behaviour of humans in isolation and animals in captivity is quite striking. We incorporated exercise into the performance vocabulary, as it is very similar to the repetitive behaviour of animals in captivity.

An exhibition and a zoo share the same purpose, which is for the audience to look at something—whether it is an object, a person, a performer, or an installation.

The work was really crucial in this time, and the continuation of its development was really important. It exists in two ways: the livestream of the performers quarantined in Manila, and the live performers in HongKong.

In a way, the project has expanded to engage with and fully take on the context of the pandemic. Its digital manifestation only exists because of the limitations set by travel restrictions. There has been a strong drive from all of us to participate in the work, and it has become vital on so many levels. We entered the Zoo performance as a way to keep our sanity, and it's a strange contradiction to experience it as a space of refuge.

XTIn our original plan, you were supposed to be in the exhibition space every day for nine weeks. Then we changed it to the configuration of the physical body, performed by Hong Kong dancers, and virtual body, performed by you and your collaborators in Manila, with the physical and virtual bodies sharing the same 'space' together in the first phase.

This was meant to be followed by the second phase when you and your team would perform in Hong Kong, with a finale of everyone together in the last week. Because of the sudden third wave in Hong Kong, your trip has been put on hold again. We are stuck at phase one.

The impossibility of your presence and the channelling of the virtual body were unplanned. After six weeks of exhibition and performance, the connectivity through the screens made us feel almost attached to the virtual. Someone told me that she was astonished by the image of you, trapped in the monitor and looking for attention and into Thea Djordjadze's installation, .pullherawaypull. (2020), which acts as a window.

I want to ask about your experience of being on the other side, and your tactics of engaging and playing with the spectators through the screen.I sense the notion of powerlessness again in this work, as I did in previous works like Macho Dancer (2013) and Host (2015), as a result of the voyeuristic gaze. How would you describe the experience of powerlessness in this work? Is it physical or emotional?

EJPowerlessness in this performance is reflected on a systemic and institutional level, as well as on a private, individual level. As performing artists in Manila, we are dealing with rage on a daily basis. Throughout the livestream, everyone has been trying to manage their rage. We were constantly discussing how to collectively demand change, and where and how we could express this rage. What you can see in the livestream is rage that was yet to be transformed into action—a state of limbo, as rage simmers beneath.

On the private, individual level, our practice as live performance artists is situated in our bodies—our practice is about liveness, which in the pandemic situation has to be transmitted through several devices. First it is captured by the camera, then the computer has to turn it into code, it has to be pixelated, streamed, and then it comes out on the other side in Hong Kong in the TV frame in a two-dimensional virtual Zoom screen.

As live performers we have had to deal with and accept being reduced to a two-dimensional image. We have to accept it, but actually, we refuse to. I think that's the contradiction we perform in. I think we talked about how, at some point, the online performers of the Filipino team were really quite...

XTExplosive.

EJYes, explosive—compared to the live performers in Hong Kong. It is a situation. In a sense, we're trying to explode the frame. We are used to getting live attention, and now you see the audience kind of just passing by and dismissing you immediately, if you don't perform for them, for example. So there's a lot to figure out in terms of being inside the TV, and how to navigate this live interaction with the exhibition audience who are quite curious. After the second month, there have been a lot of interesting interactions that I didn't think would be possible.

I was surprised by how the Filipino performers were engaging—it was actually possible to engage from a distance. I would say that the landscape of the experience has been a roller coaster—it has gone through different stages. In a sense, this is what I wanted to happen for the performance research—that we gain a sense of experience and perspective through the act of repetition.

XTI definitely felt your rage through the performance on the monitor. Each of the five performers had a live virtual session, with each person exposed to the public in their very private spaces. I was stunned by each performers' ability to use the existing items in their private spaces and to create dramaturgy and narratives. Did you feel a sense of release after the session?

EJYeah. One of the performers, Russ Litgas, said that the Zoo performance has been a source of release, refuge, and respite, and I definitely agree. It's a ritual. It's a performance where space and time becomes suspended from the daily lockdown, so I have treated it as something special and a privilege, to still be performing and working even though we are in lockdown in Manila.

This whole period has been insightful, and has been part of our coping mechanism. It has really helped us process, digest, and confront what is happening. The migration to the virtual platform is something that we actively and stubbornly question and challenge—how do we go beyond the new digital 'normal'?

XTI have observed the visitors, who are often entranced by the video performance. It's very personal and real. What happens in the virtual performance manifests what's going on in our world with this global experience of quarantine.

I remember when I spoke to you about this exhibition last year, and the whole idea of having a physical body in an exhibition, which you felt resonated with your interests in durational performance. How did you arrive at that point of interest, from performing mostly in theatre spaces, in festivals, and on tours, to performing without a stage, in an exhibition setting, for months?

EJA durational performance is not a finished product, in the sense that you perform a set routine. I was interested in the exhibition platform—in the durationality—as part of a long creation process, which is very important for me in making work. Zoo is a performance-research project to Manila Zoo, which is the third part of the 'Happyland' series. It looks at human-animal relations through the spectacle of Disney and animal captivity in zoos, and now through our own experience in our private enclosures.

What you can see in the livestream is rage that was yet to be transformed into action—a state of limbo, as rage simmers beneath.

The performance as it currently stands is the result of the pandemic, and it is very different to what we first imagined doing. What was important was getting this sense of performing in an enclosure, which was, in the beginning, the exhibition space, and to experience how it is to be looked at and to perform constantly.

Sometimes the audience's gaze is an incentive for performance, even if you're resting. As long as you're being gazed at, the rest becomes a spectacle. I was thus really looking forward to this live durational exchange. It has brought me to a different kind of creative crisis at the moment, relating to the virtual frame and how to stubbornly insist on liveness in the time of Zoom flatness.

XTThat's a collective crisis. We are all thinking about jumping out of our screens. We're all going flat. When you talk about the work as a process, I want to bring up the topic of public participation. The project has always been conceived as performance research—a work in progress, where the spectators' gazes become part of the work.

There have been situations where viewers have wanted to be more than observers. I want to ask you how you go about protecting and defending the work. Perhaps I can share an unusual case. There was one visitor who came to the exhibition quite frequently and always spent one or two hours in the space. He was very interested in the work, and one day he came in wearing similar clothing to the performers. He asked our exhibition staff whether he could try being a cat in the space, and acted out for about an hour.

We've discussed how to deal with situations when visitors want to be part of the performance—a performance that has no stage or threshold. How do you frame the work?

EJYeah, so this Zoo fan we had when the exhibition was still open was unexpected. It was the first time that I've encountered such a desire from an audience member. I was thus quite fascinated with this person who was captivated with the work. I think it was also during my session performing on the livestream, when he joined during the last hour. There was a discussion with Jasmine at Tai Kwun and she thought that he was harmless, so she allowed him to join for that last hour, when there were not so many people visiting.

I was really curious. It brought on a whole discussion about whether we should allow audiences to participate, and to what extent, and with what limits. We have talked about the integrity of form, of intention, which involves a lot of dialogue between the Manila and Hong Kong teams. This is something that the Zoo fan didn't have. My reservations were based on the fact that I didn't have this dialogue with that person: I didn't know what his intentions were. Where was he coming from? And of course, if he interacts with the audience, he doesn't have the tools—let's say safety protocols—that we've installed, or we've talked about.

There are a lot of things that are undetermined. It was an interesting situation that gave birth to this whole discussion of where the limits were in terms of the audience participating in the work. That was fruitful, in a sense.

XTI think one of the crucial things that you mentioned about having visitors wanting to be part of the performance is that they shouldn't assume they are a performer of the work. They are not equipped with the artist's voice in interacting with other visitors.

I want to mention Silvia Federici's text, Caliban and the Witch (1998), which we discussed at the beginning of the project. The ideas of eco-feminism in the text were quite an important anchor at the beginning. Could you talk the idea of eco-feminism in relation to your work?

EJI do subscribe to eco-feminism as it aims to decolonise women, nature, and the future. Women and indigenous people's power, wisdom, and interrelations with nature were vilified, invalidated, and persecuted through witch hunts, which coincided with imperialism and missionary work as a civilising 'tool' to bring salvation to 'savages'.

We are in this current situation because of our collective history of imperialism and capitalist patriarchy, and the work is about the state of violence and constructed superiority of humans in relations to other species, and nature overall. Now with the pandemic, there's a drive towards digitisation, where everything is dematerialised, including our lived experience, which could result in a loss of our remaining humanity.

The performance amplifies and mirrors psychosis, which is collectively being felt by everyone. To perform this insanity is to insist on our shared legacy of violence that humanity continues to inflict on nature. We have to acknowledge and accept this violence that we've inherited and continue to enact. The work addresses that from the inside of our own, private enclosures and how we consume content right now. It's a stark reminder of how we've been caught off guard, with everything migrating online.

It's scary. Big data is a new oil and tech billionaires are amassing so much wealth from this pandemic, and in the process installing surveillance capitalism. We need to start managing our dependence on the 'cloud' and to situate our lived experience in our localities.

In a sense, we're trying to explode the frame.

XTDo you think you will be able to go back to the way you worked in the past? Or live the way you lived in the past?

EJI don't know. If you really think about how we've been overworking ourselves, being busy and flying around, the past is not exactly a good situation to go back to, and it has led us to this pandemic. To go back would just be to repeat this situation, somehow. Post-pandemic, I would hope that we are able to construct ways of living sustainably.

All creation processes are different. Each work demands a different condition and different research processes. It also depends on funding resources, your team, and the socio-cultural context that you're workingin. The conditions of structural production are definitely going to change as well.

I guess the kind of work that we would want to do is very different from ideas that we had pre-Covid-19. I think everything is going to change, and hopefully for the better. Live performance requires a live creation process, and so I definitely believe in the necessity of live performance in general. It's something that we have to fight for.

XTThe Manila Zoo (work-in-progress) performance was presented at the Taipei Arts Festival (31 July–13 August 2020), with the work staged in a theatre space through Zoom. Could you tell us about this version of the presentation?

EJTo clarify, Manila Zoo was commissioned by Künstlerhaus Mousonturm and co-produced by Taipei Performing Arts Center, Tanzquartier Wien, BIT Teatergarasjen, Bergen; Rising, Melbourne; Kaserne Basel, and Singapore's Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay. The showing in the Taipei Arts Festival was part of the creation process, for which the piece was presented as a work-in-progress. The theatre premiere of Manila Zoo will be shown at Künstlerhaus Mousonturm, Frankfurt, in April 2021.

Zoo was commissioned by Tai Kwun Contemporary within the frame of My Body Holds Its Shape. It is a durational performance-research on the proposal of Manila Zoo within the context of the exhibition, and further developed in response to pandemic restrictions. Zoo and Manila Zoo manifest differently according to their respective contexts. The continued investigation from both contexts has deepened the creation process and has been mutually beneficial.

The location and set-up at the Taipei Arts Festival demanded a different dramaturgical choreography of time and space. I mean, in the theatre you have maximum 90 minutes, whereas in the museum it is five hours, so it has to be choreographed precisely. It feels more like live cinema, because it's in a theatre, and there are 200 audience members are looking at the screen.

We acknowledged the fact that the work was to take the form of a disembodied performance. It was an amazing situation in the sense that there were four Filipino performers in Manila, one in Brussels, while the technical director and the tech team were in Singapore. The performance was then funnelled to the Taipei theatre space, where it wasreceived by a Taiwanese audience. There was also a soundscape in the theatre space, composed by a German collaborator.

It's like magic that the work happened simultaneously in different locations. I find it fascinating that one is in two places at the same time: my physical body is in a room in Manila, but my image was livestreamed together with all the other performers and projected onto a large screen in a Taipei theatre. It's quite futuristic.

From Hong Kong, we continued our stubborn insistence on our liveness and the materiality of the body. In theatre, we've pushed physical intensity to reference the cybersex industry—we've evolved to this perspective to zoom in on the live, primal sexual body.

XTIt's been an emotional roller coaster for us in the past months. What is your ultimate resort when confronting frustrating situations?

EJI mean, I've had my fair share of frustrations and explosions; I guess we're all in this new situation. The distance amplifies a certain miscommunication. I think I've learned a lot from this. In the end, it's learning to accept and let go of things that you cannot change, especially now.

In July, I was exhausted and drained. Not because of the artistic process, but with managing the production logistics. We attempted to fly to Hong Kong during the travel ban and the only way out was with an Overseas Filipino Workers exit clearance. It is a necessary process for all Filipinos who work abroad on an employment contract, such as nurses, domestic workers, seamen, construction workers, and so forth.

As artists with short-term engagements, we normally travel on tourist visas. We then had to deal with the systemic violence that OFW's have to comply with. One has to submit a ridiculous amount of documents as well as take several medical examinations and required seminars, a process made more precarious by the pandemic. Halfway through the process we dropped the prospect of going to Hong Kong as the pandemic and restrictions were getting convoluted on both sides.—[O]

Manila collaborators and performers: Bunny Cadag, Cathrine Go, Russ Ligtas, Joshua Serafin.

Hong Kong performers: Chan Chun Wai Ivan, Chan Wai Lok, Sylvie Nadine Cox, Yang Hao, Ho Sheung Hei Kenny, Li Ka Man Carman, Liao Yuemin Sudhee, Tse Yu Ling, Yau Ka Hei, Yeung Hei Yan Harriet.