Francis Alÿs on Borders and Games in Hong Kong

In Partnership with Tai Kwun Contemporary

Francis Alÿs. Photo: Amanda Kho.

Francis Alÿs. Photo: Amanda Kho.

In 2001, Francis Alÿs responded to an invitation to the 2001 Venice Biennale by sending a peacock in his place. Such playfulness is characteristic of the artist's practice, which will be presented in its full scope for the 59th Venice Biennale (23 April–27 November 2022), where he will represent Belgium.

Alÿs was drafted by the Belgian army to Mexico in 1986, where he has developed an interdisciplinary practice centred on dynamics in urban space and geopolitics. Having completed work with an NGO on recovery efforts towards the aftermath of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, Alÿs drifted towards an artistic practice, leaving his previous training in architecture behind.

Confronted with the density of Mexico City, Alÿs began making sense of the city through its local residents, capturing their 'presence on the urban chessboard.' Between 1993 and 1997, the artist collaborated with sign painters, including Rotulistas Juan Garcia, Enrique Huerta, and Emilio Rivera to copy his oil paintings. The project called into question the myth of artistic originality, further explored in The Fabiola Project, made up of a growing collection of over 600 reproductions of Jean-Jacques Henner's 1885 portrait of Fabiola.

Such expansions are indicative of an artist who moves beyond the confines of the studio. Through the 1990s, Alÿs activated his own position in urban space through performances such as Fairy Tales (1994), where he moves through the city as a blue strand from his jumper unravels behind him; or Paradox of Praxis 1 (1997), which sees him push a block of ice across Mexico City, before it gradually disappears, recalling the ephemerality of works by artists such as Richard Long and Hamish Fulton.

In the 2000s, Alÿs' videos took a more geopolitical turn, with The Green Line (2004) revisiting an action from 1995 when he walked from a gallery in São Paulo around the city, trailing a leaking tin of green paint behind him, this time along the Israel-Palestine border, as a reflection of the term 'the Green Line' attributed by the 1949 Armistice Agreements.

In recent years, the artist has withdrawn as the main protagonist of his videos—all accessible on his website—to give space to children instead. His series of videos capturing children's games around the world have become a key part of his practice, with examples including Hopscotch (2016), capturing a group of children in Iraq's Sharya Refugee Camp, as well as Reel-Unreel (2010–2014), developed for dOCUMENTA (13), and capturing two children reeling and unreeling spools of film through the streets of Kabul, touching on themes including the Taliban's ban on film as well as portrayals of Afghanistan by the news media (the work's title is a play on what is real versus unreal).

In 2018, Alÿs returned to Iraq upon an invitation from the Ruya Foundation to develop Sandlines, the Story of History (2020)—his first feature-length film. Taking the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement as a departure point, the artist invited children from a small village near Mosul to impersonate historical figures and moments, 'revisit[ing] their past to understand their present.'

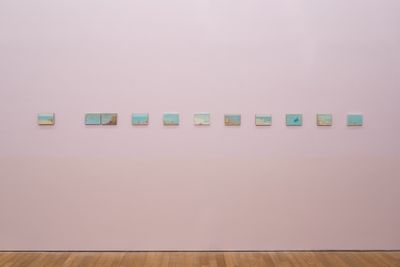

The film's East Asian premiere occurred in Hong Kong as part of his solo exhibition Wet feet __ dry feet: borders and games (28 October 2020–27 March 2021) at Tai Kwun Contemporary. Also included in the exhibition are works drawn from The Logbook of Gibraltar, recently shown at Art Sonje Center in Seoul (31 August–4 November 2018).

In this edited transcript of a talk that took place at the exhibition's opening, Alÿs joins the exhibition's curator, Xue Tan, and Tai Kwun's head of arts, Tobias Berger, to discuss its key themes alongside his trajectory as an artist.

XTFrancis, the first time you came to Hong Kong was in 1997, just before the handover, when you were circumnavigating the globe for The Loop (1997), which involved travelling from Mexico to San Diego without crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

You returned in 2017, which is when we started discussing Hong Kong's past as a colonial city saturated with migration history, and with a very unique geopolitical status. You were just telling me over lunch that you never consciously chose to do works related to borders; this has been categorised by other people.

In most cases it was not my initiative.

XTYet some of your most iconic artworks have been related to borders, including The Loop and also The Green Line, where you walked along the Israel-Palestine border with a leaking can of green paint.

Yes, retracing what is still called the Green Line as a result of the 1949 Armistice Agreements.

XTIn 2018 I visited the exhibition The Logbook of Gibraltar at Art Sonje Center in Seoul, which explored connections between different continents and ideologies.

Many of the works from that exhibition travelled to Hong Kong for Wet feet __ dry feet: borders and games, including your most recent project, Children's Games. You now have over 20 videos of children playing in different countries—Afghanistan, Iraq, Mexico, Europe, and now Hong Kong.

This most recent trip of yours to Hong Kong is particularly remarkable considering the travel restrictions as a result of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. What inspired you to come?

That's thanks to you guys. We started this conversation quite a while ago, and it had to come to some sort of conclusion beyond an exchange of emails; it had to reach a state of celebration and production. We all are in this state of limbo in terms of the near future; everything's very uncertain.

When I started, there was no internet, or very little access to internet, and we were so ignorant. But that ignorance freed us.

From a personal point of view, coming here was a sort of acceptance of the present circumstances to sort of beat the virus. This is the way travel will be at least for the next year. It's a different pace of travelling; it's adaption. It's not going to stop production.

The production was an important part, as well as the way in which Xue and Tobias maintained the conversation over those years, which leads you to want to have this moment of confrontation, and to be there, even if it's just for a few days.

TBMexico, like Hong Kong, is a major city that is very dense and chaotic, but also quite organised, as you told me. Do you think it was Mexico that inspired your early performances and plays for which you were also a 'resident traveller', as I always call it?

To make a long story short, I didn't choose to move to Mexico. I was drafted back in the mid-80s by the Belgian army. You could do social service with what they called 'developing countries' at the time.

So I went to work with an NGO in Mexico as an architect, and it's really my encounter with the megapolis of Mexico City that made me switch from architecture to visual arts.

I had been practicing architecture for like five or six years by then, and to be confronted with such an immense physical mass made me want to withdraw; to subtract rather than to add more material. And certainly there was the inspiration of people like Gordon Matta-Clark, who was subtracting material, recycling, and taking advantage of what existed, and gradually I shifted from architecture to visual arts.

It was also the first time I was really experiencing what it was like to live in such a dense urban structure, and I didn't really know how to deal with it. I was trying to find a way to justify my presence.

I was living where I still have my studio in the centre of the city, and there were a series of characters performing very peculiar acts, which didn't make much sense but sort of justified their presence on the urban chessboard.

XTAre they still there?

They've changed, I mean there are probably new ones, but there are always people doing things that you can't make any sense of.

My condition as a foreigner probably made me look at them without understanding the reasons behind their attitude or activities, but I think the first project I did was very much inspired by those people.

XTWas that Turista (1994)?

Turista was a moment when I was still keeping the attitude of an observer. I was saying clearly: I am an outsider; I can only talk as somebody who looks from the outside.

I think there was a slow progression to becoming more proactive in my way of interfering, intervening, and establishing a dialogue with place.

But in many ways, getting back to your question, it was my encounter with Mexico that made me shift and adapt to a particular performance practice, because it seemed like a much more efficient way of reacting to the urban environment I was confronting.

Earlier, Tobias, when you were talking about how I have developed a language to articulate with—I want to remind the audience that I am a visual artist and there is a reason for that: I am not particularly good at articulating the mechanism of my process. I do it through images. I am not always able to define it in words. I want people to look at it as images and sometimes articulating them reduces the power of the image.

TBIt is more like a visual language that you articulate with.

XTA couple of weeks ago, I watched The Paradox of Praxis 1 again, where you push a block of ice across Mexico City.

At the end of the video, you are surrounded by a group of children and they are kind of laughing at you and not understanding what is going on. It made me realise that your connection with children started long before the Children's Games.

I think the mechanism was always inspired by children's games, through these non-articulated rules that are set and enacted in a very intuitive way.

During the first 10 to 15 years, I was the main protagonist of my videos, and gradually children have taken over as the main protagonists. I think it's the natural phenomenon of aging, I'm afraid [laughs]—of wanting to withdraw and pass on the lead.

The scale of the projects has also grown. They started involving more people, and my natural capacity for dialogue is just better with children than adults. I connect more easily, and I find it much easier to collaborate with them.

The Gibraltar project largely came out of a disappointment of working with adults, and I turned to kids instead, totally transforming the original scenario.

I saw that for the wall text in the exhibition, you chose the phrase: 'The need to anchor an idea into reality', which came from one of the diaries of those projects. I was thinking about it this morning. The Loop is a good example because the physical result of that project was a small postcard announcing that I would go from the Mexican side of the wall—or 'fence', back then—to the other by going around the globe.

I could have simply left the travel, which took about a month back then, as a rumour, or as a concept. But I think the need to put myself as the instigator tests and ultimately transforms the idea.

The idea will evolve because it is confronted with a reality that this is very different from what was imagined. You start with a very pure and simple concept, and while you start producing it, little by little you compromise, and it changes into something different, which ultimately is the response to your original impulse.

But the process in which it will become something else is the learning experience, and that's what eventually leads me to the next project. It's all the questions that are raised along the making and how it changes the original premise into a different product.

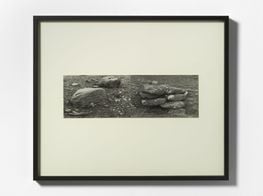

In the case of the Gibraltar project, we started with real boats and fishermen and ended up with these model boats and a much more metaphorical image. So it is important to have those different steps.

TBIn the works that deal with children's games, it is about group dynamics—it's about how kids or adults work together, play together, and so on. But how metaphorical is that for you? How much is it related also to how politics work?

I think you gave me part of the answer when we started talking about filming some children's games here in Hong Kong. It came up because you told me that your kids were playing a game called Contagion.

During the first 10 to 15 years, I was the main protagonist of my videos, and gradually children have taken over as the main protagonists.

It was a very interesting situation where the children were reflecting the conflict of an adult society in their own way by transforming it into a game.

The paradoxical aspect of it was when we were filming, and the kids were chasing and 'contaminating' one another, they asked what it meant. They couldn't understand the concept, and even when we wrote it down, they couldn't grasp what contagion was about, but they had heard the word and felt the need to integrate it into their own micro-sized society and turn it into a game to sort of mock the adult world.

XTSince 2011, you have travelled to Afghanistan many times, starting with an invitation from dOCUMENTA (13), where you filmed a children's game called Reel-Unreel. The film shows two boys rolling reels of film through the village. Is that a response to the Taliban's ban on film?

I was invited in 2010. It was my first visit, and there were many things that struck me. One of them being the children's ability to roll the reel with the stick—they were particularly good at it.

Looking back, before I went, I was in a sort of crisis with the idea of film, video, and moving image in general. I am part of the generation that has lived through the transition from analogue to digital.

The contract changed, and I wanted to address the subject of film, in the same way that I was dealing with sculpture when I did the ice block performance, you could say. And the same way that The Green Line dealt with my activity as a studio painter doing non-studio practice and going back and forth between the two.

Fast forward to 2010, I was trying to understand how to deal with film. What is my relationship with film, at a time when millions of videos are being put online every week, every month? And some of them are really good, done by kids in a garage in Jakarta.

Anyway, I got to Afghanistan and I encountered the situation of the children with the wooden stick, and I visited the film archive where the Taliban attempted to burn all the film, and where all sorts of cultural conflicts with image and representation have occurred.

The absurdity of an international artist being invited to a place where he has absolutely nothing to do and knows very little about can sometimes provoke something that has been cooking for quite a while. An idea materialised in this context, with the kids running after a wheel, which could be exchanged for a reel of film.

The media's image of Afghanistan, which is all about destruction, is a fiction in itself. The reality of any place going through conflict is that where the conflict happens, it's hell, but five kilometres away, normal life goes on. The image given by the media is unreal. Hence the title Reel-Unreel.

Everything quickly fell into place, and we started filming. Very often when I'm in that situation of discovering a completely different culture, I ask people to take me to a place where there might be kids playing on the street, because I find it's a way of being able to make contact, both by watching and filming, and seeing how people react to the fact that you're filming. It's a very quick entry into the reality of production in a place whose cultural codes you know little about.

XTCould you talk about your work in Iraq that resulted in your first feature film, Sandlines, the Story of History, which is included in the exhibition's programme?

I was invited in late 2015 by the Ruya Foundation to do a project in a Yazidi refugee camp, and the first video project we did there was the filming of the hopscotch game, which is showing in the exhibition.

I was blown away by the mass of information and the complexity of the situation there, and I very quickly understood that I would need to go back several times before being able to have more proactive projects.

In total, I produced six short films and a feature film, but it was really a progression from a documentary position; from making short films as an observer, to intervening in a minor way into the situation I was filming, and moving on to what became this sort of a historical fiction that Sandlines is.

Sandlines is based on a historical event that took place in 1916 between the French and the English. It's called the Sykes–Picot Agreement. It's basically a secret agreement that was signed between those two parties to divide the collapsing Ottoman Empire.

It's referred to as a 'line in the sand' because it's an abstract line crossing what was mostly desert. It has essentially shaped the Middle East as we know it today, and all the conflicts that have come with that agreement.

Originally, it was gonna be a short-to-medium-length film. It wasn't intended to be a feature film. As I developed the scenario I realised I needed to give it some more context, and it grew into what eventually qualified as a feature film.

The protagonists are the children from a small village near Mosul. The boys are shepherds, and the girls are either shepherds or they clean the stables. In the morning they go to school; they take off with their flock of sheep and come back in the late afternoon, and that was when it was filmed. The film happened in two shoots, one in October 2018 and the second one, about five or six months later.

I asked them to impersonate historical figures, such as King Faisal, Sadam Hussein, and so on, and I was interested to see how they would interpret those characters and a series of historical events in their own way.

Because it was largely based on improvisation, when I did the first cut, I quickly realised I would need to go back to fill all the gaps and try to link all the episodes together. We went back to the village—it's basically seven families, each of them living on one of the hills.

We presented the first cut, which opened the discussion about how we would unfold the second part of the filming. Whereas in the first shoot, only the boys participated—as habitually happens in Iraqi culture—in the second shoot, suddenly all the girls wanted to participate.

With the agreement of the families, that opened up a completely different field of possibilities and eventually gave me a sort of exit point to what is a cyclical repetition of historical events.

We were a very small crew: one local Iraqi artist who was helping us, an interpreter, and the driver. It was a very low budget production, but that's the way to function in those situations.

There were still pockets of Islamic State violence here and there, but nobody took it seriously, and to a certain point I would say that the children protected us. It was a very interesting scenario where we ended up feeling very safe all through the different shoots.

TBShould we ask the audience for some questions?

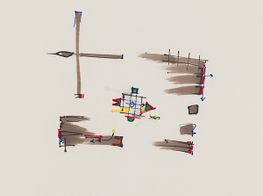

Anon 1I'm curious if you could share whether the acceleration of the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean has changed how you have seen the work that you did in Gibraltar? And could you tell us more about what the two forks represent on the map that is in the exhibition?

The two forks are just a very simple metaphor for the bridging of the two continents. But you're right to point out that when I did the project, the migration phenomenon was much lesser.

I was asked earlier why I chose that particular topic back then. I think it's simply because I had moved back to Europe for a couple of years. And after 20 years of being away, I felt like a migrant myself. I couldn't recognise the place I had left, nor myself, 20 years later.

My interest in spending my energy on that particular topic had a lot to do with my own situation and my own history, which is somewhat always the case. Any project is part of your own personal history one way or another, as was the case in Afghanistan—it's not the place that gives you the idea, it's the idea that's usually carried along and it sort of materialises elsewhere, and becomes about that place, but originally it came from your own personal situation and concerns, questioning, and so on.

It's not because you go to a very exciting place that you suddenly have new ideas that pop. They're with you from before, and you just find a way of materialising them.

Anon 2A question regarding the years after your studies in architecture. I remember reading a biography that describes you working in Belgium as a craftsman to collect enough money to spend time in Mexico City.

Where did you read that? [laughs] That's true.

Anon 2Can you talk about this relationship between work and play?

Work is play, in the way I conceive it at least. Last weekend was a good example—I was with a long-time collaborator and we were filming and it was very playful.

Play is the right word, but it's what we're most passionate about and what we love doing. So I don't disassociate the two. Work and play are one same activity to me.

Anon 2Maybe I could reframe the question in relation to the context of Hong Kong. Generally, for a lot of students who study the arts, the first job they might get is not as an artist, they become an art teacher in order to have this other space to become an artist.

It's a slippery space. I could have continued practicing as an architect, and then do art on the side, but I found it very conflicting to do both.

I think that sometimes it takes the absurdity of the artistic operation to bring some sort of sense to a situation that stopped making sense.

I liked architecture, don't get me wrong, it's not like I left it out of disappointment. But I don't think I could have done two activities that require being passionate and engaged, in parallel. I would paint apartments and work as a waiter or whatever—I would do anything just to make the money and create the time to dedicate myself to the arts.

I think one thing I have noticed in the younger generation—I'm not talking about the Asian artist community as I don't know enough about it, I am talking about Europe and even Latin America—is that they have this fantasy, this image, that their first show is gonna be perfect work, in a perfect space, with the perfect audience, and it doesn't work like that.

If I were to look back at my own experience, it's by having made some mistakes that I eventually managed to find my own language. But it took a lot of mistakes; a lot of failures.

When I started, there was no internet, or very little access to internet, and we were so ignorant. But that ignorance freed us. I know I did some works that had already been produced by other artists. But not knowing it and having repeated that sort of creative process eventually led me elsewhere, which was my own language.

There is no first perfect work. It happens to some but not to most. And it takes a lot of compromise, a lot of mistakes, and a lot of courage to reach a stage where you can start finding your own path.

All I am saying is that there is a moment of grace in one's career where you have to give it all. Give it all while you are young, because you'll have all the time later to choose out of the avalanche of images, ideas, and attitudes, which may or may not be interesting to develop.

I think as time passes, you become more aware of your limits and you start censoring yourself. Instead of feeling certain, you start doubting, and in that sense you're less creative. Your language may potentially become better—in the articulation of an idea, or the illustration of a concept—but the creative impulse is different.

It is very important to just get things out while it happens and without analysing, without wanting it to be this perfect product. You'll have plenty of time to do it later. That's what I would tell my son.

Anon 3I wanted to ask you about The Fabiola Project, which you have collated over the years. Initially you were talking about the instinct of doing something very quickly and presenting it, but in this case, the work has taken many years to collate.

Very early on, I was very interested in the process of copying. I was working with sign painters who were copying my own images. It was a game of me giving them an image, they would do their own version, I would do a version on the basis of their interpretation, and so on. It was this back and forth and our image would change slightly in the process of collaboration.

Anyway, this led me to an interest in this 1885 portrait of Fabiola. At first, I just started buying the reproductions at flea markets because I was intrigued by the repetition of that image. But then I realised that that same image was also copied in Latin America, Lebanon, Russia, and so on.

It made me question the status of an icon. What is an icon? Is an icon defined by official art history? Or is an icon defined by, in this case, what seems to be an amateur painter's obsession with a particular image?

As you mention, it is a project that has happened over a number of years. It started as my own initiative, and then it became autonomous, because people started sending me copies from different parts of the world.

I sort of stopped looking for them or collecting them. The collection is well over 600 paintings now. It's growing out of a collective initiative. So even if I wanted to stop it, it just grows, by its own inertia. I think I found the first one in 1994, so it's been going on for many, many years now.

Anon 4Hi, I was wondering if you could talk a bit about the self-censorship you mentioned that comes with age? As well as this interaction as an outsider working with groups of people. How do you navigate the limitations with these kinds of invitations?

What limitations?

Anon 4For example, when you were saying you were invited to Iraq to work as an invited artist. How do you navigate your place or justify your presence?

Do you mean as a foreigner?

Anon 4Not necessarily as a foreigner, but as an artist. There is this sort of aura of being someone who is a different actor. How do you navigate that?

I was invited so I didn't question it at first, I just accepted the invitation and the origin of the dialogue. I mean the series of projects I developed there were simply because I had been asked to. There are many layers to your question.

XTCan I share my observation on this one? I read that you were questioning the purpose of doing art in Afghanistan when you are confronted with poverty and major destruction. I think Iraq's invitation came because it has a lineage to your work.

Essentially you are asking about the relevance of art within a situation of conflict, and I think that sometimes it takes the absurdity of the artistic operation to bring some sort of sense to a situation that stopped making sense.

I mean it's a very peculiar process, but there is a moment where the society, because the surroundings are collapsing, is more open to a different reading of its reality, and it's also more in demand of a different reading of its reality.

I think you could question why an outsider has to take that role. I personally don't think that one excludes the other, I think that you could have initiatives from locals as much as outsiders in trying to establish a dialogue.

What I'm saying is that it's a complex issue, and the whole debate of cultural appropriation is very strong at the moment. The whole concept of an international artist could be put into question within that discussion.

I choose to believe in cultural exchange—creating bridges, dialogues, and so on. It's a personal decision. I cannot justify it. I think the reason why the whole debate of cultural appropriation came up is as a result of excesses in the opposite direction, and it's a necessary debate.

I don't think that one excludes the other, but I understand that it could be a transitional space through which it's necessary to go in order to recreate a better balance. But it's a very complex issue and it has many layers and I think it's important to question and to be conscious of it.—[O]