Korakrit Arunanondchai’s Images, Symbols, and Prayers

Korakrit Arunanondchai. Courtesy Kukje Gallery. Photo: Chunho An.

Korakrit Arunanondchai. Courtesy Kukje Gallery. Photo: Chunho An.

Bangkok and New York-based artist and storyteller Korakrit Arunanondchai has long explored belief systems by connecting two worlds—the tangible and intangible—across mediums, from video and painting to installation, music, and performance.

For Image, Symbol, Prayer, the artist's recent solo show at Kukje Gallery, Seoul (15 December 2022–29 January 2023), Arunanondchai created a floor installation made of compressed ash and clay that intended to evoke a collective gathering around a fire.

Along the edge of the room, a prayer text embossed on the floor dealt with themes of life, creation, and letting go of order: 'In the beginning there was discovery /New nightmares, to challenge sleep /The need to impose order unto chaos /We create this world through unanswered prayers,' the first half reads.

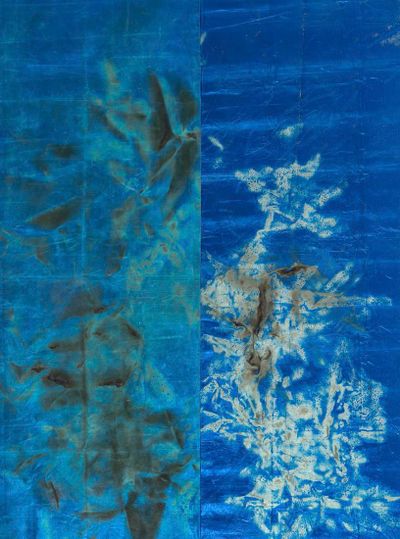

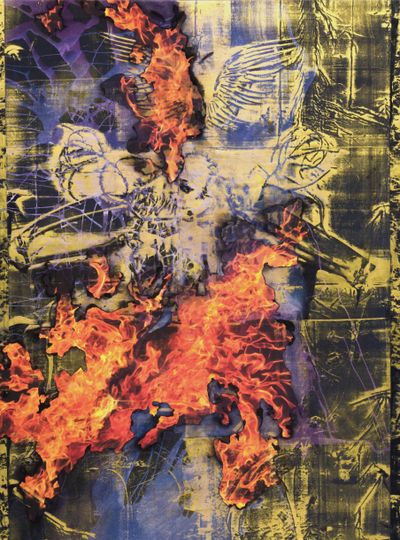

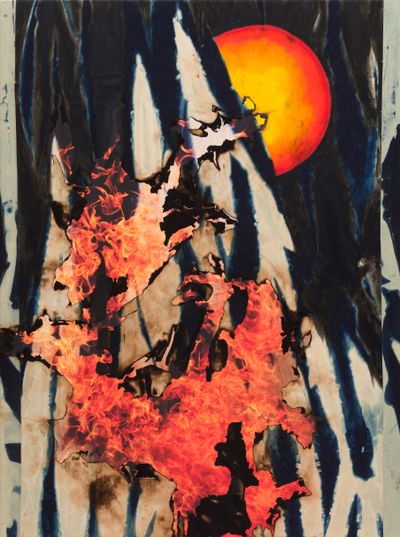

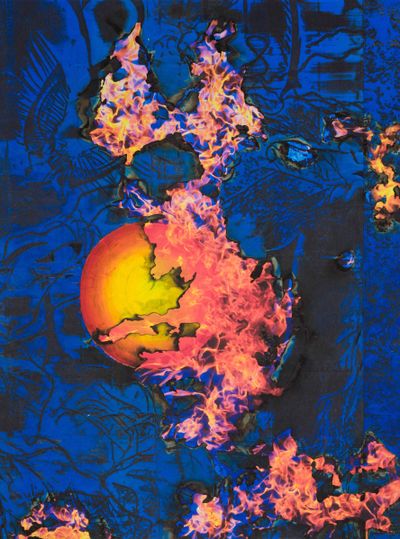

Above the text hung works from two painting series, 'History Paintings' (2012) and 'Void (sky painting)' (2022). 'History Paintings' comprises bleached denim set on fire, photographed, and placed atop photographic prints alongside imprints of the artist's body. Hues of red, blue, and yellow emulate flames; several motifs come into view: leaves, the sun, and birds.

For example, the burning abstract imagery of The Mocking Jay (2022)—an acrylic polymer on gold foil placed on bleached denim and prints—features gold, fire, handprints, and denim vestiges that recall a phoenix's wings.

Contrasting 'History Paintings', with its rich symbolic imagery, are three paintings from the 'Void (sky painting)' series. Several burnt cracks are depicted in an open blue field, the whole composed of acrylic polymer on blue foil covering bleached denim.

As the artist mentions in the following conversation, both series are closely related to his video works: Songs for living (2021), a collaboration with Alex Gvojic, and Songs for dying (2021), both shown most recently at Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Zurich (2021–2022) and Art Sonje Center, Seoul (2022).

Centring the loss of the artist's grandfather, Songs for dying collages footage of the latter's last moments with mourning and shamanic rituals around the Jeju uprising in South Korea (1948–1954), and anti-government and anti-monarchy student protests in Thailand during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the video, the artist sings 'La Vie en rose' (1947) to his grandfather. Interspersed in these intimate frames are visual references to spirits of aquatic living systems: a sea turtle, haenyeo (Jeju Island female divers), as well as the forgotten dead from the Jeju massacre. In one scene, student protesters hold up three fingers, referencing the mockingjay, a sign of resistance from the Hunger Games film series (2012–ongoing).

Set to feature at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris (15 February–7 May 2023), Songs for living is a music-video style collage of fragmented footage: bonfire rituals, Tai-chi dancers, and unicycle delivery riders that look like Garuda, the Buddhist mythological bird-god and national symbol of Thailand.

Unsurprisingly, Arunanondchai has long been interested in the themes of life and death, creation and destruction. For his solo show at MoMA PS1 in 2014, he presented the two-channel video installation 2012-2555 (2012).

A video showing his grandparents, among others, creating a garden, was screened within a set referencing a standard Thai funeral, with chapel-like archways printed on the wall behind and a seemingly dead life-sized mannequin surrounded by pink plastic flowers.

The title, 2012-2555, references the massive floods in Thailand in 2011. The artist imagines 2012 as the end of the world, the year corresponding to 2555 in the Buddhist calendar.

At MoMA PS1, the artist also showed three painting series, including 'Untitled (History Painting)' (2013). Since 2012, Arunanondchai has expanded his 'History Paintings' series to include versions that connect to different video works.

'Untitled (History Painting)', for example, is related to the video Painting with History in a room filled with men with funny names (2013), which features footage of modern American artists, such as Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, juxtaposed with images of Thai youths in blue jeans.

The video includes the artist interviewing the head at the all-boy school he attended, as he attempts to identify himself as a 'denim painter'.

In this conversation, Arunanondchai expands on the mediums and philosophies behind his work and their intricate interconnections; how they shape a practice rooted in creative anarchy, and where stories grow as the artist evolves.

SJI was struck by your recent show at Kukje Gallery in Seoul in many ways. The exhibition comprises a 'History Paintings' series that feels quite different from your typical multimedia-styled works. Could you elaborate on their provenance?

KAI have been making these paintings alongside the installations for Songs for dying/Songs for living (2021) over the past two years. So the show at Kukje Gallery and the earlier one at Art Sonje Center feel like an inversion of one another: one is a gathering around a screen, which functions as fire; the other is fire gathering and dancing around you.

My process for making video installations and paintings feels very co-dependent. Often, I find something unspoken for in one medium that can be found within another.

SJYour previous exhibitions, including the one at the Art Sonje Center, centred on themes like cycles of creation/composition and decreation/decomposition, often by juxtaposing different timelines and histories.

At Kukje Gallery, a linear narrative emerges, perhaps due to the prayer text on the ground, which starts with 'in the beginning'. Did you mean to create a starting point for the exhibition? How do you conceive of beginnings and ends within a cycle?

KAI always try to reimagine the idea of a cycle in the form of a spiral. For me, the prayer text can start anywhere. Where it ends, it begins again. But this doesn't mean we're in a loop forever.

I wrote the text as I write my video scripts. There is a sense of sincerity but also banality; spirituality that is hopeful but also profane. In the end, the text is a prayer that remains unanswered. The prayer text takes you to the void where beliefs are formed and differences can appear.

SJWhat inspired the prayer text in the floor installation?

KAEstablishing the ground's relationship to the sky was important for me in this exhibition. In rituals of fire, the irreducible matter of ashes returns to the ground, while prayers, wishes, and thoughts turn into smoke. Fire always points upwards to the sky because that is where god exists.

I wanted to use materials that feel profane and drained and try to transform them towards a feeling that resembles something spiritual.

In Image, Symbol, Prayer, I wanted to make the floor into a stage that compressed ash and earth into this dark matter that is this irreducible togetherness. Mythical time is always a place before the beginning and after the end; I wanted the ground to feel pre-historic or post-history in this way. To me, the prayer text running along the edge of the exhibition space feels like a personification of ground matter—a form of speech that tries to escape the ground into the sky.

SJRead this way, paintings from the 'Void (sky painting)' series depict a sky. What do you mean by 'void'?

KAThe void is different from emptiness. It's like a green screen—or in the case of the 'Void (sky painting)' paintings, a blue screen. It's a space for something to be projected on. The space longing for a belief.

SJThe vantage point of this series is a bird's-eye view, which contributes to the feeling of a void in the show. What prompted this choice?

KAA bird's-eye view is also a god's viewpoint. Fire always points to the sky as if it's sending a message to whatever occupies the void above. So the denim painting on the ground is also like the earth and its inhabitants.

SJMoving onto the ground, who is the 'we' in the prayer text?

KAI, and possibly anyone who reads those sentences and identifies with them.

SJThen, as a temporary collective, we read the prayer text together. I've read that Heroes (2006), the American TV series, has influenced some parts of the text. Could you expand on the influence of popular culture on your storytelling?

KAThe first two lines of the prayer text were paraphrased from an ending voiceover in a Heroes episode by the narrator. I don't particularly love the series, more so the self-seriousness of its tone. Series like Lost (2014–2010) or Heroes, which try to show this existential, serious, and deep perspective, felt very nostalgic for the early 2000s.

Coming from a place where everything was supposed to be sacred felt exhausting and more of a tool to push capitalism and the status quo forward. I wanted to use materials that feel profane and drained and try to transform them towards a feeling that resembles something spiritual.

Making art is a way to develop desires and try to fulfil them through creation, hoping that one day it feels enough.

If something can make you believe in life's endless possibilities for a moment, even though it was purely made for entertainment, perhaps it is good enough to be borrowed and used for something else.

To create artwork and be an artist is also to believe in the possibility of perspective change. That's why I love to borrow from pop culture—for its application and exhaustion as a material to make a large group of people into believers. People like me.

Watching TV and consuming pop culture always leaves me empty and a stronger feeling arises from that consumption built up by desires. Making art is a way to develop desires and try to fulfil them through creation, hoping that one day it feels enough.

SJBesides pop culture, multiple motifs struck me in the show, such as red spheres, body prints, and symbols of the sun, fire, and ground. Titles too are notable, such as Ecstasy on the mountain top, God is in the ground (2022).

What story did you want to tell?

KAEcstasy on the mountain top, God is in the ground came from a thought I had while I was picking sites for my performance in Aspen, Colorado: whether it would be on top of a mountain or in the forest areas below.

I thought people shouldn't be allowed to go to the top to gather and form rituals, and prayers should come from below. The top of the mountain is a space for projecting thoughts and wishes; the moment you reach the top, those wishes die. The ecstasy from praying is in anticipation of knowing your wish hasn't been denied yet. It's a space of possibility.

I've been painting and thinking about the mockingjay, a phoenix and reference to the main character in the film Hunger Games. She symbolises resistance within a dystopian fantasy world where democracy is 'permitted' by a ruling class when blood sacrifices are made.

Student protesters in Thailand also held three fingers together to symbolise the mockingjay in the protest movement against the military regime and hegemonic ruling class.

However, the paintings in the Kukje exhibition are not about storytelling, but suspending the process in which specific sets of relationships are made between the formation of images, symbols, and prayers. All of these ask for change, for something to die and be born out of it.

Painting is a medium in which the process and subject can truly support each other and make you feel something impactful while escaping time and language. That was my hope in making this body of work.

SJIn these paintings, fire is both the subject and process. The lines in the painting, made from the fire, are especially mesmerising. They are where stories in the gap are created. What can we read from your use of materials?

KAThe line where immaterial and material meet and start to blur is important to me; I think that's what happens in the ritual space when human beings meet around a fire.

In the paintings, one part is leftover painting residue. The other is a digital reproduction of the materials burning—parts that are now long gone and turned into 'memory'. Looking at the painting, when this border starts to blur and the fire is felt again, is akin to a dream.

SJWhat do you mean by 'dream'? How do dreams differ from rituals in your work?

KAWhen you think, sometimes you add things and subtract others to see the individual. A collective gathering such as a ritual can be like that.

Dreams are more powerful than reality. It's similar to why movies can be impactful. They cancel certain things from the frame to allow other things that we have not been conscious of to come in. In the ritual, the individual gets subsumed into the collective. But in the end, something else also returns and becomes part of that individual.

SJBesides Michael Marder's philosophy, what are some other influences on your artistic thought and practice?

KAI'm influenced by many sources: books, movies, and music. In a way, my artistic practice is made up of references to these. For instance, Michael Marder's book Pyropolitics: When the World Is Ablaze (2014) references many books I read, such as The Psychoanalysis of Fire (1938) by Gaston Bachelard.

SJWhat sparked your initial inquiry into jeans, which can be read as a symbol of youth culture, the history of labour, and Western forces of globalisation? I am particularly intrigued that you bleach the denim before setting it on fire. What does the garment and gesture mean to you?

KAI often think about the idea of being unable to access authenticity. The misinterpretation or mistranslation of that search forms culture and denim can symbolise this feeling.

I wanted to use the 'ghost' in the artwork to represent something obscure and hidden inside of everyone.

To have an impact, you can take something away and let it grow into another pathway without truly knowing it and still feeling its weight—such as what is unsaid because we don't know the right word, but don't want it to remain silent. I think that's why I work with denim; removing the indigo dyes through bleach to create these patterns feels like a process.

SJA line from the prayer text reads: 'the ghost possesses nothing'. Your work can be read as a mediation between spirits and humans. What are ghosts to you?

KAI wanted to use the 'ghost' in the artwork to represent something obscure and hidden inside of everyone. The ghost is a non-human carried through the collective and requires a body in space and time to possess. It's something that is penned up and never goes away.

Yet in meeting with a subject or form, it is allowed to transform and mutate in meaning. The set of relationships that the ghost carries through time and space has always been one of an unfulfilled desire, with feelings of anger, pain, and loss.

Subjects that have been erased through history but remained penned up and stored in non-human objects and spaces—Michael Marder refers to theirs as the story of defeat stored in the ash, ready to reignite into flames. I think that's why the ghost is always connected to the space of death but remains in this realm. —[O]