Kyung An on the Enduring Spirit of Korean Experimental Art

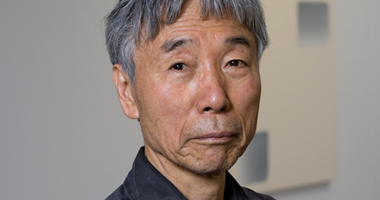

Kyung An, Associate Curator, Asian Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. Photo: David Heald.

Kyung An, Associate Curator, Asian Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. Photo: David Heald.

What significance does a survey of Korean Experimental art from the 1960s and 1970s hold in the United States in 2023?

The 1960s and 1970s were a period of massive change and growth for South Korea. Major reforms were headed by Park Chung Hee who became president of the Republic of Korea in 1963 after a military coup in 1961. Park's reforms led to unprecedented investment in industrial and technological development, export, and urbanisation, with significant aid from both the U.S. and Japan.

In September, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York will open the first institutional exhibition in the U.S. dedicated to Korean Experimental art (silheom misul). Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s (1 September 2023–7 January 2024) is co-curated by Guggenheim Associate Curator of Asian Art, Kyung An, and Kang Soojung, Senior Curator at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul.

President Park's authoritarian regime imposed strict censorship on Korea's media and culture, including the press, film industry, and visual arts. Artists of the time nonetheless continued to practise and organise exhibitions with an increasingly international outlook, in parallel with early globalisation and advances in technology and media dissemination. Art historian Cho Soojin noted:

Some of these avant-garde artists were sympathetic to the idea of "nationalist democracy" under the Park Chung Hee regime ... but others were critical of the military dictatorship ... Nevertheless, both camps still regarded the art world as part of a state-led developmentalist enterprise ... [and] came to stand for institutional resistance to established art and the desire for an alternative art system, rather than the articulation of an anti-nationalist political ideology.1

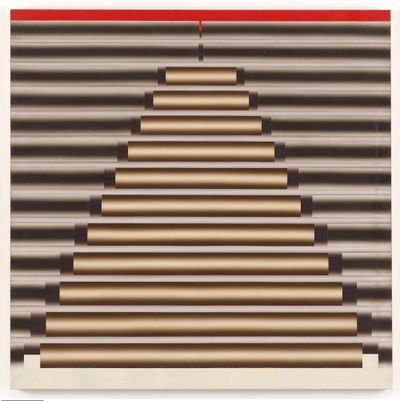

While discourse around 20th-century Korean art has often centred around Informel, the avant-garde abstract painting movement of the 1950s and early 60s, and Dansaekhwa, the monochrome painting movement of the 1970s, the spotlighting of 1960s to 1970s Experimental art in Only the Young hones in to acknowledge the pivotal period in-between.

Loosely organised around the various groups formed by artists during this period, several of which overlapped in membership—such as the Avant Garde Association (AG), Space and Time (ST), and the Fourth Group—the exhibition also recognises landmark historical presentations such as the Union Exhibition of Korean Young Artists (1967) in Seoul and the Paris and São Paulo biennials in the 1960s and 1970s, where Korean Experimental artists interfaced with artists from around the world as the international avant-garde.

Only the Young co-curator Kyung An was born in Korea and moved to the U.K. at a young age. In 2014, she completed her PhD in Korean art at University of London's Courtauld Institute of Art. An is the co-author with Jessica Cerasi of Who's Afraid of Contemporary Art? (2017). She has written widely on Korean artists including proponent of Dansaekhwa, Ha Chong-Hyun, and interdisciplinary artist Lee Seung-taek, both of whose works are included in the exhibition.

From 2019 to 2021, An was a Curatorial Research Fellow at The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, during which she, together with Kang Soojung, researched Korean Experimental artistic practices of the 1960s and 70s.

The product of years of research, Only the Young is enormously diverse in its breadth of media, with some 80 artworks spanning photography, sculpture, painting, drawing and mixed-media works, and video. It is accompanied by an expansive publication, the first on Experimental art in English, with contributions from leading scholars, curators, and historians of Korean art, as well as documentation and translations of original sources including articles and artist manifestos.

Only the Young first opened at the MMCA in Seoul (26 May–16 July 2023). Following its Guggenheim presentation, the exhibition will travel to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where it will open from 11 February to 12 May 2024.

In this interview, co-curator Kyung An speaks with Misong Kim about the genesis of Only the Young, expanding on the significance of the artists of Experimental art, both within and outside the context of 1960s and 1970s Korea.

MKCan you tell me about your background, from Korea to London and New York? What attracted you to studying Korean Experimental art?

KAI was born in South Korea and moved to England when I was eight. England is home. Except for my immediate family and a few cousins, all my relatives still live in Korea. We visited Korea every year or two and spoke Korean at home; the culture was always part of our upbringing.

[Experimental artists'] sense of radicalism, of reckoning with the shifting realities they faced, and their brazen and courageous attitudes to new mediums and methods were all very inspiring.

I applied to study mathematics for my undergraduate but ended up taking a gap year and reapplied for a degree in art history. I was interested in the intersection between history, politics, social studies, and cultural studies, which all seemed to come together in the subject.

I was accepted into the Courtauld Institute of Art—that was an eye-opening experience for me. After my master's, also at the Courtauld, I interned at the Guggenheim in the Asian art department. When I first learned about Korean Experimental artists, I felt the same jolt of excitement I'd felt when I was learning about Russian and Soviet artists during my master's. Their sense of radicalism, of reckoning with the shifting realities they faced, and their brazen and courageous attitudes to new mediums and methods were all very inspiring.

MKCan you talk about your research journey? How did your PhD in Korean art, the influence of the late art historian Kim Mikyung Kim, and your time as a curatorial research fellow with The Andy Warhol Foundation culminate in Only the Young?

KAMy PhD included a chapter on Experimental artists, but it was more about how Korean artists in the post-war period—from the 1950s to the 1970s—were thinking about art and subjectivity as they began to increasingly exhibit abroad.

Kim Mikyung was the first to foreground these artistic practices in the early 2000s under the rubric of Experimental art, although the term had been used here and there before, even by the artists themselves. They had been overlooked somewhat by art historians, but there was this momentum and real effort by many art historians, artists, and critics, including Kim, to bring to light Experimental art in a more critical way.

I joined the Guggenheim as an assistant curator after my PhD. I felt strongly that a show on Experimental art was right for the institution, given its history of major solo exhibitions on Korean artists like Nam June Paik and Lee Ufan, who had intersected with Experimental artists.

Park Hyunki, for instance, has talked about how impactful Paik had been on his practice. There was also an article on Paik in Gonggan (Space), which was the most widely circulated magazine on art and architecture in Korea at the time. Artists avidly read about him.

Lee Ufan, whom we associate more closely with the Dansaekhwa movement of the 1970s, exhibited with some of the Experimental artists at the seventh Biennale de Paris in 1971. Additionally, the Guggenheim has a history of revisiting the post-war era with shows on the Gutai Art Association from Japan, Zero Group in Europe, or Italian artists of Arte Povera. To expand that narrative, I proposed a show on Experimental art.

Once the exhibition was confirmed, I received the Andy Warhol Foundation Fellowship, which allowed me to travel to Korea regularly to conduct research and interview artists, as well as Paris and São Paulo to do more archival research on the international biennials Experimental artists partook.

During that time, the Guggenheim approached the MMCA in Korea to co-organise the show. They have the largest collection of Korean Experimental art, so we felt they were a natural partner.

MKCan you walk us through the exhibition's design, chronology, and artwork highlights?

KAThe exhibition is split over three floors of the Guggenheim's tower galleries. It spans the mid-1960s to the late 1970s, although many included artists continued their practice beyond this period and are still making art. Some moved on to abstract painting, others to different artistic explorations, but that spirit of experimentation still lives on.

The exhibition design at the Guggenheim tries to embody the dynamic ways in which Experimental artists thought about art at the time.

The exhibition is thematically organised, loosely following the various groups active at the time. Many of these collectives overlapped in membership—artists who were part of the Avant Garde Association were also members of the Space and Time group or partook in the Fourth Group—so an artist might feature in two different sections of the show.

The exhibition design at the Guggenheim tries to embody the dynamic ways in which Experimental artists thought about art at the time. They were drawn to stimuli from everyday life and tried to move away from abstraction championed by Informel, which they believed had become staid and conservative, having lost its avant-garde urgency.

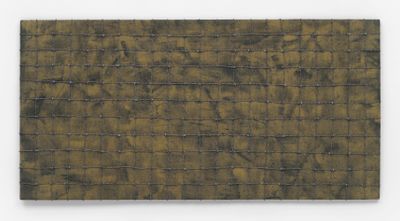

They turned to materials and processes they'd never previously encountered as Seoul rapidly urbanised and the nascent republic of South Korea modernised. For instance, Ha Chong-Hyun used industrially manufactured barbed wire and springs and Kang Kukjin, neon lights, reminiscent of neon signs that began to light up the city at night.

Experimental artists resisted the older, established generation of artists and structures of art. Thus, we too wanted the exhibition design to go against the grain. This is reflected in the choice of wall colours, the shapes of platforms and vitrines, and the architectural design. Things are always slightly off-kilter. There is also a chronology of performance art on two of the galleries, and an archival section on each level.

I felt strongly that we should include a selection of works by each artist to give a sense of their overall practice at the time, rather than a single representative artwork that attempts to illustrate the curator's point.

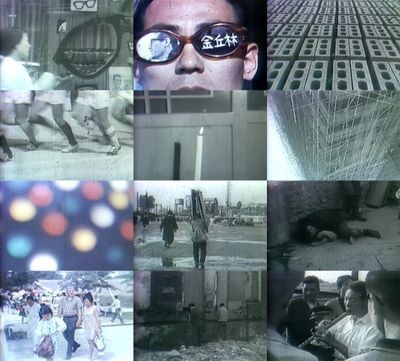

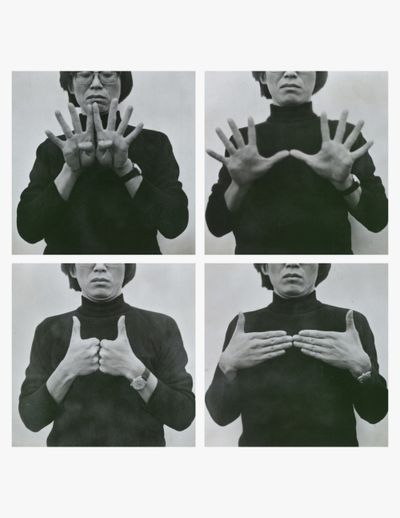

Kim Kulim's early forays in assemblage in the form of painting are shown alongside his experimental film, The Meaning of 1/24 Second (1969), which is in our collection. Lee Kun-Yong's majestic Corporal Term (1971–2023), an uprooted tree sourced locally, appears to be transplanted into the gallery and is shown along with his performance-based works.

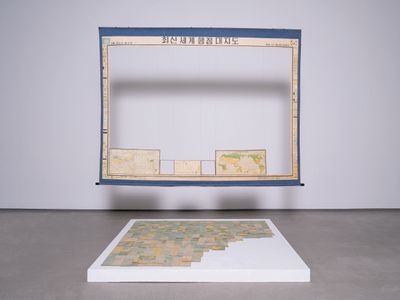

From Sung Neung Kyung, there is 세계전도, 世界顚倒, An Upside-Down Map of the World (1974), and works such as Apple (1976) and Here (1975) that rely on the documentary characteristic of photography. His newspaper cut-out works that deal with restrictions on freedom of expression are also on view. There are some women artists too, but it was not easy finding extant works. Jung Kangja's Kiss Me (1967–2001), which was refabricated in 2001, is in the show.

MKYou mention it being harder to find women artists. Can you talk a bit about women of the Experimental movement?

KAWomen artists like Jung Kangja and Shim Sun Hee participated in the Union Exhibition of Korean Young Artists in Seoul in 1967, which was considered the first moment of experimental tendencies in the history of Experimental art in Korea. Unfortunately, many of the works did not survive.

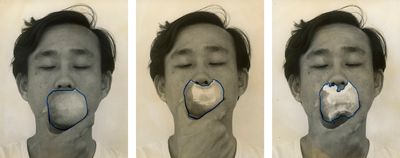

Jung Kangja, for instance, was a member of the Sinjeon Group and the Fourth Group. As the first artist to stage a nude performance in Korea—Transparent Balloons and Nude (1968), a photograph of which is included in our show—she was much sensationalised by the male-dominated press. The gaze cast on her differed from those on her male counterparts.

[Jung Kangja's] work often turned to the female body as both evidence of discrimination and an instrument of criticism.

Interestingly, her work often turned to the female body as both evidence of discrimination and an instrument of criticism. Consider Kiss Me originally shown at the Union Exhibition of Korean Young Artists, an engorged pair of brightly painted lips holding a domestic-use rubber glove and a severed woman's head between its teeth.

Women's role in 1960s society was full of contradictions—clinging to deep-seated Confucian values, but facing financial opportunities and sexual autonomy. Much of this also intersected with issues of class. Jung also collaborated with other artists from Sinjeon and the Fourth Group on many performances that were critical of existing art and social systems. Jung ultimately moved on to painting and passed away in 2017.

MKWhy is it important to you for audiences in New York and the U.S. to see this exhibition at this time?

KAI'm glad we have the opportunity to present this slice of history and cast light on new protagonists of this era. I hope it can provide some context for what we see happening in contemporary culture today. It's been fascinating to see the rising interest in Korean culture—K-pop, cinema, K-dramas—in the U.S. and globally.

Only the Young is also an invitation for discovery. Over the past few weeks, I've been installing the exhibition with our art handlers, many of whom are artists. Every time we unpack an artwork there are so many questions—how did the artist do this? Why did they do that? They're curious because they've never heard of these artists. These are not the names taught in art history classes but the work speaks to them.

On the flip side, a Korean supporter of the museum was surprised to learn that art forms like Experimental art existed during a period typically associated with the authoritarian regime of Park Chung Hee. Whatever piece of political or art history you are familiar with, there will be something to discover for everyone.

MKIn your essay in the accompanying publication, you write: 'The gaze of Western critics was mired in orientalist assumptions that often overlooked the local context of production, which itself was marked by hyper-urbanisation and accelerated modernisation, and overshadowed by the repressive policies of an authoritarian regime.'2

How does this exhibition redress such assumptions and provide a fuller understanding of the sociopolitical contexts of 1960s and 1970s Korea in relation to the development of contemporary art?

KAIt's such a complicated question to answer. Can this show redress such assumptions? I don't know, but we can certainly try. It's hard to deny that many Experimental artists were impacted by what they saw happening abroad contemporaneously, intercepted through Japanese and U.S. magazines, as well as articles printed in Korean periodicals and self-published journals.

Examples are abundant. ST group discussed and dissected texts like Joseph Kosuth's seminal essay 'Art After Philosophy' (1969), while AG journal contained translations of texts by Lucio Fontana and on Land art. They were voracious in seeking out new visual languages.

It's hard for us, whether inside or outside Korea, to avoid making comparisons. I showed Lee Kun-Yong's Corporal Term to a curator, who said that it reminded them of Giuseppe Penone and Maurizio Cattelan's trees. But of course, Lee's tree is so different, because its context of conception and production is completely different.

I'm hoping that through the wall texts and visual materials provided in the exhibition, we can highlight the importance of the local conditions in which these works existed, were perceived, and circulated.

MKIt is interesting—even today, you can see a lot of exhibitions in Korea that look towards Western art history.

KAI think it's inevitable, art history as a discipline is so Western-centric. But I'm less interested in who did it first—why they did it or how is much more interesting! That's something I hope people can focus on when they see the exhibition at the Guggenheim.

MKWhat role did the U.S. play in the development of post-war Korea, having influenced art and artists in Korea through the second half of the 20th century?

KAI'm no expert, but there was the United States Information Service (USIS), which was the operating name of the overseas arm of the United States Information Agency (USIA) created in 1953. They set up offices and services across Allied countries to try to influence public attitudes through culture.

In South Korea, the USIS played a crucial role in disseminating information on American arts and culture. They had a library where artists could access books and magazines and organised talks and public programmes as well.

In accounts relayed by Informel artists of the 1950s, the USIS is mentioned as a vital source of information where they accessed publications such as TIME and Life. And of course, we cannot underplay the politicisation of art and culture that was central to the operation of such agencies during the Cold War.

The 1960s and 1970s are also a pivotal period to re-examine, not necessarily through the lens of American soft power, but more expansively as an era of unprecedented information dissemination enabled by developments in telecommunications. TVs became ubiquitous in people's homes and channels to access information opened up, creating a sense of connectivity and globalisation, well before the onset of the internet age. —[O]

1 Cho Soojin, 'From Avant-Garde Experiments to Experimental Art: A History of Alternative Korean Modernism,' 18. In Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, edited by Kyung An and Kang Soojung, 16–31. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2023.

2 Kyung An, 'The Global Village: At the Paris Biennial of 1973,' 35. In Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, edited by Kyung An and Kang Soojung, 32–49. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2023.