Lee Kang-So and Choi Byung-So

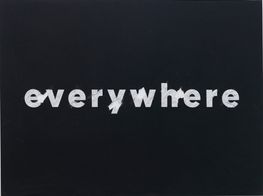

Image: Lee Kang-So and Choi Byung-So. Courtesy Wooson Gallery.

Image: Lee Kang-So and Choi Byung-So. Courtesy Wooson Gallery.

Korean artists Choi Byung-So and Lee Kang-So are holding simultaneous solo exhibitions at the Musée d'art moderne de Saint-Étienne Métropole, on view through to 16 October 2016. Though their names are most commonly associated with Dansaekhwa, the artists maintain distinct styles that situate their practices outside of the monochromatic painting movement.

The two played instrumental roles in the burgeoning scene of experimental art in 1970s Korea, when the avant-garde was pitted against Park Chung-hee's dictatorial regime. Choi and Lee helped establish the Daegu Contemporary Art Festival in 1974.

The festival was integral to the Korean avant garde art movement, and was the first large-scale event organised by a collaborating group of artists. Choi was an important member of the festival for years, and quickly established a signature aesthetic with his material explorations in pen and paper.

Choi is best known for using newspaper as his medium of choice, turning typically data-filled broadsheets into studies of patient repetition. Using pen and pencil to methodically 'erase' the contents of the page, the resulting papers are left fragile in their torn states but also heavy from the rich layers he applies. His tools, mass produced and cheap, recall an era of modern Korean history where resources were scarce and artists produced work pragmatically. But newspapers have a far deeper meaning for the artist, a life-long paper subscriber who revisits memories of a post-war childhood in his process.

Lee took inspiration from Dadaist happenings, executing poignant performances in the early seventies that would become some of his best-known work. At the 9th Paris Biennale he turned heads with Untitled-75031, in which he scattered chalk across the gallery floor and tied a chicken to a central post; it was left to leave its footprints across the space.

Since then, his investigations into the potential of images have journeyed from installation to video to paintings of acrylic on canvas. Many of his paintings feature recurring motifs of ducks, boats and deer. However in recent years those silhouettes have become pared down with minimal use of line. He is driven by Confucian and Buddhist principles, and a desire to capture fleeting moments of life.

In this interview, the artists discuss their relationship to Dansaekhwa, and the role of Daegu, their shared hometown, in the Seoul-centric world of contemporary Korean art.

IMSince the landmark exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) in 2012, your work has been connected to the Dansaekhwa movement. Do you feel comfortable with this categorisation, and if not, why is it important to make this distinction?

CBSAt first glance, because the work is entirely covered in black mineral-like material, it can seem like Dansaekhwa. But because the tools I use aren't painterly but literary, I don't keep Dansaekhwa in mind while working. I had wanted to open up a new horizon of painting, rejecting existing traditions through a method of erasing newspaper with pen, and again erasing that with pencil.

LKSWhen I received the invitation to participate in the Dansaekhwa exhibition at the MMCA, the organiser had initially wanted to use the term 'Dansaekpa' ['monochromatic wave'], which I conveyed was not a suitable name. I even vehemently protested this at the press conference for the following exhibition, after learning that the title had suddenly been changed to 'Dansaekhwa'. The reason was that up until that point, artists who had worked for years and amongst the countless others across the country, had not once ever expressed their art to be 'Dansaekhwa' or 'Monochrome'. Three others also at the press conference were of the same opinion. Afterward, even during the exhibition run, you didn't see any of the artists consenting that their works were 'Dansaekhwa'. Although this is certainly just in my opinion, I think that the organiser misinterpreted the word 'Dansaekhwa' of the monochromatic quality of ink and literary paintings in traditional Asian formalism and the meaning of Dansaekhwa as used in the Monochrome of Western art.

I think that the Monochrome forms achieved by artists like Malevich, Fontana, Klein, Reinhardt, and Ryman were generally formal propositions that followed changes in traditional thought according to painting mediums, moderation of expressions, and investigation of painting itself.

IMYou're a seminal figure to modern Korean art, including your involvement in founding the Daegu Contemporary Art Festival in the 1970s. What distinguished the work you were doing in Daegu to the art scene in Seoul at the time?

CBSContemporary art in 1970s Daegu fell into the categories of the scholarly (or elite) mindset, the amateur, and the experimental. Before the Daegu Contemporary Art Festival opened, there was 'Korean Experimental' (the exhibition was in the spring of 1974 and the art festival opened in fall), and this became the launch pad for contemporary art in Daegu.

If the Daegu Contemporary Art Festival was a place of festivity for abundant and jubilant contemporary art, 'Korean Experimental' was a writhing, groundbreaking presentation that was meant to open a new world of art for ebullient young artists. It wasn't just Daegu-based creators but conscientious artists scattered across the country participating, not minding the critical gaze of the older generation but boldly expressing their own world. If contemporary art in Daegu was of the raw stuff dripping blood, Seoul was a contemporary art that had already been polished, refined, and moderated.

LKSThe Korean art world around the 1970s was not only fed up with the slow mindset of the established modern art scene, but within the difficult conditions of a developing country was also full of the adventurousness of young artists susceptible to the influential tides of contemporary international art. This sense of adventure and resistance gave birth to several collectives, catalysing an active scene. Nevertheless the establishment made a display of force, and the young artists pursuing contemporary art were yet lingering in the suburbs.

At the time I was traveling between Seoul and my hometown of Daegu, and with a younger colleague who had come up to help me in my studio, organised the Korean Contemporary Art Invitation Exhibition. It was an event that began under the concept that small collectives weren't enough to disseminate contemporary art into the mainstream, but that it would take a large-scale art movement. In those years, there was a long-running exhibition hosted by the Chosun Ilbo newspaper that invited mostly figurative, abstract, or Informel artists. In Daegu, we invited 30 contemporary artists from the new generation, from Seoul to the countryside, with funding from the Daegu Department Store's Dabec Gallery.

The following year in 1974, after organising Korean Experimental (6-11 March at Dabec Gallery, with 27 artists) and seeing the gradual increase of artists turning to contemporary, we held the '1st Daegu Contemporary Art Festival' (13-19 October, with 67 artists) at Keimyung University. Although there weren't a lot of people pursuing contemporary art yet, what set the festival apart was that we were able to develop an era of burning passion and mutual support in a time when hostilities were high between different generations, alma maters, geographical locations, and art tendencies. Of course, I think that the artists were also able to have a greater sense of confidence and responsibility because of the fact that they were showing one another a completely free pursuit, outside of what they each called contemporary.

After that in 1975 Park Seo-bo led the 1st Seoul Contemporary Art Festival, in 1976 Kim Jong-Geun started the Busan Contemporary Art Festival, and in the same year Gwangju artists organised the Gwangju Contemporary Festival. In particular, as the Daegu festival grew, it filled with video art and happenings, and Japanese artists also participated with installation work. Its influence was felt not only on the artists themselves, but on locals who grew closer to art and universities that began to transform with contemporary art education.

IMThrough minimal gestures, elements of the everyday become key to your work. Why is this connection to the real important to you?

CBSWhether in the past or present, I tend to work honestly. It's been a long time since I abandoned the notion of creating a masterpiece. As I hover on the border between art and life, I make work that is meaningful even as it is meaningless.

Every day I erased the accumulating pile of newspapers with the writing utensils that rolled next to my desk, and because I used to exhibit for the cost of a pack of cigarettes I wasn't even able to publish a catalogue of those works. Even though those pieces from the 1970s and 1980s have been swept away, disappeared without a trace, I haven't once clung onto that.

LKSIn 1973 I received my first invitation for a solo show at the Myeongdong Gallery in Seoul. For the exhibition I moved in furniture (tables and chairs) from an old dive bar in the city, and for a week I served alcohol to visitors exactly like you would in a bar. The audience was able to experience a variety of situations, some thinking the gallery had actually become a bar, others understanding it as art, enjoying the alcohol and conversation. I even visited on occasion and was able to experience it as a visitor myself.

The idea behind the work was that the tables and chairs had taken on tremendous form, filled with the lives of the owner and patrons of the bar. From the surfaces of the wood-paneled tables and chairs I felt like I could see and hear the countless scratches and burns from cigarettes and hot pans, rags cleaning them until they shined like curios, visual and auditory hallucinations like silent screams. This is a world that cannot exist even though it wants to exist. For it to exist something must stop, but everything is moving and even my mind is ceaselessly changing and every particle is in flux. The dive bar piece was sharing that experience. Even I am but a fluctuating visitor.

This hallucinatory experience, as a reflection of everything in my mind, cannot help but be uncertain. No matter how much one calls for analytical and rational thinking, it cannot bring about certainty. In Zisi's Doctrine of the Mean, there is a line that says something along the lines of, 'Although the human mind has an clear ontological aspect and an aspect of the concrete from the real world, this is but one state'.

I'm more interested in the possibility of realising the ilhoek ['one stroke' or 'holistic stroke', an idea from Qing Dynasty painter Shitao that the meaning of 10,000 strokes can be achieved in one] in a balanced state that's at least a little bit closer to 'sincerity', rather than expressing the joy, anger, sorrow, and happiness revealed in the everyday of human nature. So even though I know it's a futile endeavor, I keep trying in my work.

IMNewspapers have been your medium of choice since the 1970s. How has your perspective of this particular material changed over the years, and do you feel its significance in contemporary society has changed?

CBSThe fact that I've continued to work with newspapers till now is because newspapers, like writing utensils, are everyday readymade objects. I've subscribed to papers since I was young and I still subscribe to them today, but with the rise of new information platforms, I'm not sure what the role of newspapers will be in modern society. These days I also erase completely empty broadsheets that have yet to be printed on.

My earliest memory of newspapers is from the first semester of my second year of elementary school. I had been handed a large sheet of paper with the lesson printed on it, instead of a textbook in the classroom. As publishers and bookbinders were destroyed by bombings during the Korean War, newspaper companies printed school lessons onto broadsheets and distributed them. I folded it and put it in my pocket, carrying it with me for the whole semester, and the paper, deteriorated into shreds by doodles and scribbles, stayed in my memory for a long time until the mid 1970s, when it emerged into the world through art.

As the 1950s were years of my childhood when I was most sensitive, I'm still not free of those sentiments. Poverty and starvation, suffering and return, life and death, pain and joy, silence and outcry, chaos and order, meaning and insignificance ... these notions still dwell within my work.

IMRepetition is a major part of your process. How do you remain connected/focused on your actions, and what draws you to this act of repetition?

CBSAs I erase I layer, as I layer I erase, the background becomes the surface and the surface becomes the background ... As they absorb and permeate one another, undergoing the process of erasure and layering, fiercely colliding, tearing and creasing, I wait for the newspaper to transform by solemn, pure touch.

For the last many years my work of erasing has undergone the same process. In the 1970s and 1980s because of my youthful passion I only erased the front pages of the newspaper. From the 1990s to the present I erased the front and back sides altogether. As I covered the entirety of the newspaper in permanent pen it carried a sense of preservation. Lately I've been emptying my mind while erasing time absent-mindedly. I've been erasing without thought, like writing in a diary as a habit.

IMFormally, your paintings have a gestural quality reminiscent of Korean ink paintings—yet you work with acrylic and oil on canvas. Why do you prefer these materials?

LKSAfter presenting my 'chicken performance' at the 9th Paris Biennale in 1975, I spent over three months in my hotel room working, focused on the question of what two-dimensional painting is. I observed what happened when you pulled on just a strand or two of fabric, strands sewn into a textile that is attached to wood that forms a canvas. I experimented with whether or not it was possible to paint on the structure of the canvas. When I returned to Korea I spent countless years on work that questioned what an image that is placed onto a canvas was. I used silkscreen on canvas, paint tubes and cans of paint covered in paint to print images, pulling at a single thread of canvas stained with the paint of an image, and even taking that single thread and painting it. They were varied attempts, work that pried into canvas painting and what structures the image.

It was maybe in 1988, on a cold winter morning when I went for a walk with my family through the zoo. On a wide frozen lake there was a hole in the middle where ducks and geese were sunbathing and splashing each other with water. In my memory, it wasn't a particularly bright period; socially and politically it was difficult. The sight of the lively animals came as a shock to my system. Could I not capture this bright, clear, alive moment in a painting? Even though it might be impossible, I thought I'd try.

Of course I was interested more in the spirit of the brushstroke rather than the depiction of the deer, ducks, and geese. Those brushstrokes abandoned the desire to depict, but with as clear as possible a mind painted as it came, with a composed body and flowing strokes without a hitch. The result varied with the viewer, who might see a duck, a goose, or another waterfowl, freely associated with the image. For me, as it wasn't a painting painted with the intent of description, I enjoyed the fact that I could make something that allowed each audience to imagine, and because I felt the hopeful possibility of the brushstroke in the action, I was happy.

Although these paintings were done in oil and also acrylic, a few years later I used mostly acrylic. Because I also preferred traditional calligraphy brushes, the water solubility seemed better suited to receive my physical body's responses.

IMYour oeuvre encompasses such a diversity of genres, from performance to sculpture and prints. What moves you between these various media and what draws you to painting now?

LKSThe reason why I experimented with installation and performance in the early 1970s was because I had read about work happening in the West, and they were my ventures based on a limitless expectation that the future of contemporary art could truly be diverse and free. From that context, a time when analyses of traditional Western painting and sculpture methods as contemporary art were languishing, I have continued my own understanding and practice of painting.

My start in video art in the 1970s was during the era of the contemporary Korean art movement, and was in part to help expand the genre in Korea. In addition, I've worked on and off with installation, prints, and photography. From the time I was in elementary school I enjoyed carrying around a camera and taking snapshots, and one day while skimming the history of photography, I discovered a strange idea. Of course, I'm sure there are lots of photographers who have thought about this before me, this most important aspect of photography. That is, that we cannot look out from another's eyes.

However, painting has always been my main interest. This is because I believe painting expresses my thoughts most sensitively and delicately. Endless cultivation and training conveys my spirit precisely in the interactions between body and brush, paint and canvas. As Shitao said, 'The act of the one stroke is so grand that it can only be seen from nature, and because the act is hidden from the eyes, most people do not know what it is'. Although I do feel sorrow at these words, I carry the belief that a bright and clear spirit can somehow be attained on some level. —[O]

Representative pieces by Choi and Lee are also on view at the Busan Biennale, Hybridizing Earth, Discussing Multitude (3 September–30 November 2016).