Melanie Pocock in Conversation

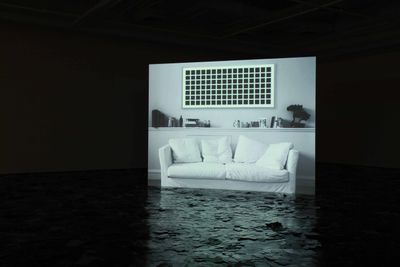

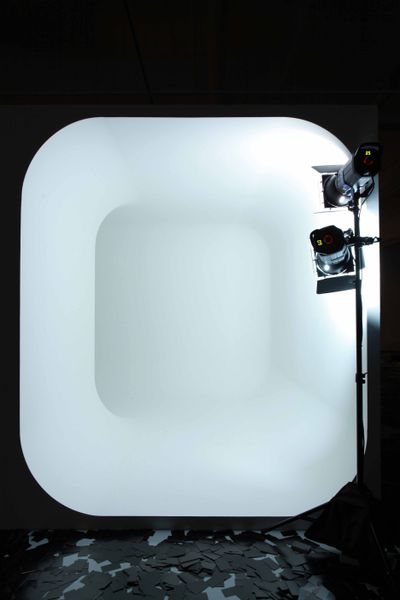

Melanie Pocock. Artwork: Camille Henrot, Office of Unreplied Emails (2016–17) Exhibition view: Dissolving Margins, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts (20 October 2018–22 January 2019). Courtesy Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts. Photo: Ken Cheong.

Melanie Pocock. Artwork: Camille Henrot, Office of Unreplied Emails (2016–17) Exhibition view: Dissolving Margins, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts (20 October 2018–22 January 2019). Courtesy Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts. Photo: Ken Cheong.

Occupying a sweet spot between autonomy, rigour and accessibility, the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (ICA Singapore) at LASALLE College of the Arts plays an important role in the presentation and discussion of Southeast Asian contemporary art.

Currently boasting five galleries in the McNally campus of LASALLE, the ICA Singapore runs a twin programme of works by students, staff and alumni of LASALLE, as well as curated international exhibitions that have been applauded by industry players locally and abroad.

Melanie Pocock is assistant curator at ICA Singapore. Pocock moved to Singapore from London in 2012 and her first job in Singapore was as a lecturer in Contextual Studies, Art History and Curatorial Studies at LASALLE from 2013 to 2014. She has been working in her current capacity since June 2014.

Pocock's first major curatorial project at ICA Singapore—titled Countershadows (tactics in evasion) (2014)—was a critically acclaimed exhibition of works by seven Singapore artists—Heman Chong, Tamares Goh, Ho Rui An, Sai Hua Kuan, Jeremy Sharma, Tan Peiling and Robert Zhao Renhui (The Institute of Critical Zoologists)—dealing with the topic of concealment.

The exhibition presented installation, sound, sculpture, photography and video by these seven artists that explored how exposure and concealment are often intertwined, each revealing the qualities and axioms of the other.

This was followed by Native Revisions (2017), which featured four Asian artists' long-term and slow-paced engagement with their chosen subject—Chua Chye Teck's immersion in Singaporean forests, Noh Suntag's return visits to the US military base near to, and the village of, Daechoori in Southwest Korea, Anup Mathew Thomas' intimate knowledge of communities in the Indian state of Kerala, and Tomoko Yoneda's persistent tracing of legacies left by Japanese imperialism.

The exhibition provided a counterbalance to the often rapid pace of production among global and local artists. The latest exhibition to be curated by Pocock, Dissolving Margins (2018)—running until 22 January 2019—presents works by five artists whose practices blur physical, ideological and disciplinary boundaries.

The exhibition, whose title is inspired by a scene in Elena Ferrante's novel My Brilliant Friend (2012), shows large-scale installations, experimental performance and prints that immerse viewers in experiences of 'dissolving margins'. Pocock has also worked on Shooshie Sulaiman's book, Sulaiman (2014), published by Kerber Verlag; and my own solo exhibition, Machine for Living Dying In (2014), at Yavuz Gallery.

In this Ocula Conversation, Melanie Pocock discusses her curatorial work within ICA Singapore, especially how her three major curated group exhibitions offer a lens to examine Singapore's art scene. She also elaborates on how she relates pedagogy to exhibition-making, as well as local, regional and international art scenes in her work.

MLICA Singapore has two lines of programming: one that presents the works of students, staff and alumni; and another that presents the practices of international artists.

Additionally, although ICA Singapore has an art collection, it operates primarily as a Kunsthalle [German for 'Art Gallery' and meaning a flexible space that shows, rather than collects, art] with an art school as its main body. How do these lines of programming intersect and what are the roles of ICA Singapore curators like you, especially in presenting critical art practices in this pedagogical context?

MPI like the way you described it—'a Kunsthalle with an art school as its main body.' To continue this metaphor, I would say that the ICA Singapore's galleries are the curatorial arms of LASALLE; while drawing on the resources of the college, they also reach outwards, creating bridges between communities of artists and the public.

In international group exhibitions at the ICA Singapore, you will often see unusual displays and groupings of artists and artworks, linked via imaginative themes. In solo exhibitions, you will see artists pursuing new concepts and stretching the possibilities of production, such as Boedi Widjaja's Black—Hut (2016). This experimental criterion underpins the pedagogical mission of LASALLE, which seeks to innovate through experimentation in art practice and discourse.

In the programme that we develop with LASALLE, we as curators work directly with students, staff and alumni of the college. These exhibitions—which range from works-in-progress to industry collaborations—enable students, staff and alumni to engage with processes of exhibition making. For many of the students, it is the first time they have considered these processes and perhaps even brought their work outside the studio. As curators, we provide the knowledge and skills to shepherd that process.

What this means is that as a member of the public visiting the ICA Singapore, you are able to see the work of artists-in-training and artist-academics alongside the work of practising artists 'out in the world'. Seeing these two strands together—we hope—allows people to connect where art practice comes from to where it can lead. Structurally, the programme enables transfers of knowledge; while applying museum standards of display to exhibitions with the college, we are also able to bring the thinking and concerns of younger generations into the international exhibitions.

MLWhen you arrived in Singapore back in 2012, what did you notice about its society and art scene? Your first projects in this region were Sulaiman (2014)—the first monograph of Malaysian artist Shooshie Sulaiman—and Machine For Living Dying In (2014)—my solo exhibition held at Yavuz Gallery. How did you find your way into the Singapore art scene and that of the rest of Southeast Asia?

MPSoutheast Asia, as anyone here can tell you, has an incredibly complex art scene. Its melting pot of influences generates very layered art forms. Singapore is often considered an anomaly—a postmodern island of financial capital—and the character of its art scene does reflect this. But it's not a 'simple' scene by any means. Its adroit image carries its own contradictions.

When I came to Singapore, I quickly realised that I would need to reconfigure my references, which until that point had been informed by my Western education. My experience of Southeast Asian culture was mostly vicarious—learning about Singaporean and Malaysian history through my mother and Chinese Malaysian friends living in the United Kingdom, for instance. The desire to get to know this ethnic and cultural half of me, on my own terms, formed a large part of my motivation for coming here.

This, I think, was the vantage from which I was looking at the art scene in Singapore. Paradoxes surrounding hybridity—feeling doubly rich at the same time as imbalanced, or neither one nor the other—are common experiences of people here, many of whom have mixed cultural backgrounds.

It seems strange to say 'back in 2012', as it was such a short time ago, yet so much has changed since then. At the time, there was a lot of optimism and a sense of anticipation. Art Stage Singapore was at its height as an art fair, art enclave Gillman Barracks had had various soft openings, and the remodelling of the City Hall and Supreme Court buildings into the National Gallery Singapore was well underway.

But amidst these infrastructural developments, there were—and many would say still are—certain 'lacks': of discourse, curatorial support and ground-up initiatives.

The two projects you mentioned—Machine For Living Dying In (2014) and Sulaiman (2014)—were critical because (and you can correct me if I'm wrong!) I think that they helped you and Shooshie clarify your practices, at points when you were both considering your positions within these art scenes.

They also enabled me to understand certain nuances of art from the region: in your case, the pathos of urban memory in Singapore and, in Shooshie's case, instinctual forms of knowledge embedded in Malay culture.

MLYou're right! And your main ways of supporting my clarification of my position were asking probing questions and thorough consideration of options. Your first major group exhibition at the ICA Singapore, Countershadows (tactics in evasion) (2014) impacted me deeply.

As I approached the exhibition, I felt as if I were descending into a cave, an association that was completely apt, given the topic of concealment explored in the exhibition, the geological abstraction readable in the campus design, and the representation of caves in key philosophical and cultural texts ranging from Plato's Allegory of the Cave to Peter Weir's film, Dead Poets Society (1989).

On the other hand, the dramaturgy in showing the works of seven Singapore artists into a coherent whole was noted; you even got asked if it was a solo show because of its achromatic scheme! What kind of politics of exhibition-making here did this project address and reveal?

MPIt's interesting that you describe the colour scheme as achromatic. For me, it was more monochromatic: that is, distinctly black, white and all the shades of grey in-between! In the exhibition, these tones had particular functions and meanings.

The white surface of Sai Hua Kuan's Something Nothing (2007), for example, was intrinsic to its illusion of a flat void. Heman Chong's Monument to the people we've conveniently forgotten (I hate you) (2008–ongoing) also operated through a form of assertive negation, the work's innumerous black cards shrouding the floor of the gallery like an inverted black cloud.

The exhibition was my way of articulating what I perceive to be a salient aesthetic in Singapore contemporary art. This aesthetic, which comprises various forms of wilful concealment, is often paradoxical; while withdrawing, or retracting from view, at times it also lures the viewer in, exposing its illusory architecture.

Metaphorically, it also expresses characteristics of Singaporean society and culture: its policy of constant urban regeneration and the sometimes passive-aggressive behaviour of its people, whose inwardness often masks outward frustration.

My interest in conditions of practice, I think, is why I enjoy working closely with artists.

Many people commented to me at the time—and they still do—that the exhibition left a strong impact on them. I think that this is because it was very performative. The works weren't simply illustrating these ideas; they were performing them. They were also performing them in a coherent way—that is, together, as a single schema. Chong's installation was very provocative; by filling the entire floor of the gallery, his installation framed every work in the exhibition.

For me, this openness, and the possibility of works 'spilling' into one another, is integral to the politics of group exhibitions. It's what makes them interesting as exhibitions—opportunities for works to conflict or harmonise with one another. In my mind, it is these potential conflicts and harmonies that deepen our knowledge of artworks and their conceptual and aesthetic operations.

MLLet's talk about curatorial philosophy and methodology. How have your formal trainings in history and curating, and your previous working experiences in research, education, public programme, marketing and writing helped shape your curatorial practice?

How does your initial encounter with artists' works move towards studio visits, and how does that develop into curatorial invitation, concept development, production and eventual presentation in the ICA Singapore?

MPI have always been interested in the conditions of how art is produced and experienced—an interest that comes from my background in history. For my MA thesis at the Royal College of Art, I analysed how transcultural politics and feelings of cultural difference influenced works by Chinese 'new wave' artists presented in exhibitions in France in the late 1980s.

My interest in conditions of practice, I think, is why I enjoy working closely with artists. For me, it is through negotiations with artists that an exhibition starts to emerge.

All kinds of priorities—the artist's, my own, budgetary, institutional—as well as the question of 'how will we communicate this' come into play during these negotiations. I don't see priorities beyond the artist's and my own as 'interrupting' some kind of sacred curatorial process—quite the contrary. I see them instead as opportunities to test the artist's and my ideas, and their traction with a wider audience.

The way you describe the curatorial process feels, to me, quite linear. In reality, questions of concepts, production and presentation are interconnected—they happen in tandem.

Configuring these tasks are among the skills of the curator—the ability to negotiate these various aspects, and to arrive at a satisfactory outcome for all those involved.

That said, there is always a beginning, and this beginning starts for me with an interest in a particular artist or artwork. I will try to identify the innate characteristics of the work or the artist's practice, particularly its affects. This will then set off various triggers—texts I have read, other artists' works—that eventually come together to form a coherent premise.

At the same time, this process has to respond to the context I am in. At the moment, this context for me is the ICA Singapore, where questions as specific as the galleries' glass facades and students' understanding of art influence which ideas I take forward.

When I presented Anup Mathew Thomas' work in Native Revisions (2017), for example, it felt relevant on so many levels, not just because of Thomas' Keralan heritage (around 10% of Singapore's residents are of Indian ethnic origin), but because of the 'slow time' embedded in his works. For me, his photographs, which can take several years to realise, provide a much-needed contrast to the precociousness and speed of many young artistic practices in Singapore.

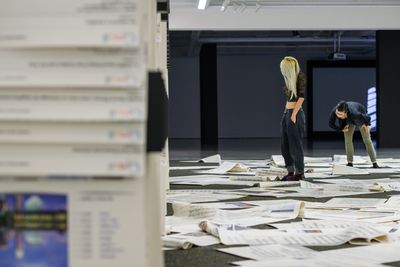

MLDissolving Margins, the ongoing exhibition at ICA Singapore, showcases art practices that plod boundaries, whether physical, mental or disciplinary.

Given how borders today are continually redrawn in global politics as a means of dealing with conflicts and tensions, the issue of dissolving margins cannot be more timely. How are the nourishing—or damaging—effects of dissolving margins examined in this exhibition, in light of global art and politics?

MPI completely agree with you, which is why in the exhibition I look not only at the aesthetics of 'dissolving margins', but also their contradictions. While 'dissolving margins' evoke a utopic vision of liberation, their limitlessness also invokes a certain fear: a desire to retract, and to re-draw trenches.

The title of the exhibition comes from Elena Ferrante's novel My Brilliant Friend, and the psychosomatic episode experienced by one of its main characters, Lila Cerullo. During this episode, Lila feels not only as if she is dissolving, but also as if she is apprehending, for the first time, the immoral behaviour of those around her.

In the exhibition, these effects of dissolving margins are expressed in works by Eng Kai Er, Camille Henrot, James T Hong, Tara Kelton and Darius Ou. But Ferrante's book also informs the exhibition in other ways. When I read it, I was struck by its visceral tone, as well as the slipperiness of the term—dissolving margins—which is sometimes translated as 'dissolving boundaries'. The novel is a bestseller, and immensely popular among women; a popularity that I think comes from Ferrante's intimate address of female friendship. To me, it is a work that acknowledges the instability of our times and the impact of emotions on courses of events.

Recently, I have been thinking about how emotions are expressed on online platforms—Donald Trump's fraught outbursts on social media, for instance. Trump indirectly forms the subject of several spam emails from political advocacy organisations in Camille Henrot's installation, Office of unreplied emails (2016–17).

In the installation, we see responses written by Camille to spam emails that she personally received. What is interesting about Camille's replies to these auto-generated emails is their ambivalence; instead of painting herself as a victim of unsolicited requests, she shows the engagement they trigger. Her responses are written in calligraphy and seem personal, but when you read them, you realise that they are as capricious and 'performed' as the spam's targeted campaigns.

One question that I have been thinking about for a while is 'what does it mean to be international?' Since I have been at the ICA Singapore, this question has been refined to: 'what does it mean to be international from somewhere like Singapore?'

Instead of focusing on biography—where artists come from—I have been thinking more and more about interactions—their potential conflicts and their frequently uneven nature. Darius Ou and Eng Kai Er are both emerging artists who operate mostly on a local level. They also come from disciplines less usually encountered in an art gallery—graphic design and dance respectively.

Camille Henrot, on the other hand, is a globally recognised visual artist whose work has been presented in major international institutions. James T Hong is a filmmaker, working in a very specific way with the post-war context of East Asia.

Tara Kelton's projects deal with the context of Bangalore as India's 'silicon plateau'. Yet, despite the fact that these artists seem 'worlds' apart, their works within the gallery have this strange, oscillating harmony.

For me, it is important that the works 'do what they need to do' and are not burdened by curatorial rhetoric. The negating premise of the exhibition—dissolving margins—I feel, aids this: it sets a framework of dissolution through which these artists' works can emerge and interact.

MLWith regards to your three curated group exhibitions at ICA Singapore, especially in examining this city-state and the region through nuanced themes, aesthetics and sensibilities, could you share your observation of how Singapore's contemporary art scene has been developing in the past five years, and where it is heading?

MPI would say that the 'lacks' I mentioned earlier (discourse, curatorial support, ground-up initiatives) have definitely changed. The National Gallery Singapore and the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art have provided platforms for discourse and debate. New artist-run spaces, such as soft/WALL/studs and Peninsular, which is led by artists Cheong Kah Kit and Tan Guo-Liang, are providing a critical counterpoint to Singapore's primarily 'top-down' scene. Together, these and existing initiatives have created a more diverse landscape, and a greater sense of an art ecology.

The mix of artists in the group exhibitions that I have curated at the ICA Singapore I think reflect this growing ecology. The juxtaposition of Darius Ou's Autotypography (2012–13) alongside Camille Henrot's Office of Unreplied Emails in Dissolving Margins, for example, creates a powerful parallel—not only between different disciplines (graphic design and visual art), but also between an emerging, local designer on the one hand, and an established international artist on the other.

Here, we see scale and complexity mirrored, yet in works by artists at very different stages of their careers. It's a provocative and exciting statement, and one that I hope inspires young artists here.

This feeling of connectedness with a diverse and global world of art is, in my view, one of the most interesting aspects of Singapore's current contemporary art scene.

Over the past five years, I've been amazed by how many artists and curators I've been able to meet simply by being in Singapore—a frequency of meetings that has been made possible through the connections of institutions here with international networks.

I think the universal themes of my group exhibitions at the ICA Singapore—mechanisms of concealment (Countershadows) and politics of place-making (Native Revisions)—have, in a small way, contributed to this growing sense of worldliness.

They offer lenses through which the particularities of Singapore's art and culture can be examined and explored through global ideas and artists. I think many of the artists in Singapore whom I've worked with identify with the paradox at the heart of this idea—of feeling as much the need to look outwards as inwards, in order to elucidate what is happening here. —[O]