Art for Justice: A Roundtable with Nick Cave and Bob Faust

In Partnership with EXPO CHICAGO

Nick Cave and Bob Faust, Facility (2019) (detail). Limited-edition print. Limited edition of 200. 9 colour lithograph. 76.2 x 53.3 cm. Signed by the artists. Courtesy the artists.

Nick Cave and Bob Faust, Facility (2019) (detail). Limited-edition print. Limited edition of 200. 9 colour lithograph. 76.2 x 53.3 cm. Signed by the artists. Courtesy the artists.

On 24 September 2020, artists Nick Cave and Bob Faust joined representatives of Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights and Illinois Humanities, grantees of the Art for Justice Fund, to kick off EXPO Chicago's EXHIBITION Weekend (25–27 September 2020), with a virtual roundtable on issues relating to mass incarceration, freedom, advocacy, and structural inequity.

The conversation, which has been transcribed and edited in partnership with Ocula Magazine, took place in honour of a limited-edition print produced by Cave and Faust, commissioned by EXPO Chicago for the last edition of the exposition. Following a tradition of artist-made prints for the Chicago International Art Exposition at Navy Pier during the 1980s and 90s, the work draws upon iconic motifs found in Cave's practice and sculptural 'Soundsuits'.

Nick Cave and Bob Faust are artists who almost need no introduction. They are both co-founders of the multidisciplinary art space, Facility, and we at EXPO Chicago have had the distinct pleasure of working with them over the last nine years that the fair has been in existence.

Recently, the artists produced Amends (2020): a three-part project, which, for one of its iterations, invited the local community to write messages on yellow ribbons reflecting on the perpetuation of racism and efforts to overcome it, which were then tied to a clothesline installed in front of Carl Schurz High School in Chicago.

Gabrielle Lyon is the executive director of Illinois Humanities. Lyon's work is focused on leveraging the power of the humanities to make Illinois a more livable state for all residents. Her work includes founding Project Exploration, a nationally recognised nonprofit organisation dedicated to changing the face of science for youth and girls of colour, as well as organising cross-sector stakeholders for social change through education both locally and nationally.

Quintin Williams, previously of Heartland Alliance, and the former campaign manager for Fully Free: The Campaign to End Permanent Punishments, is now the programme officer of gun violence prevention and justice reform at Joyce Foundation. Williams' research includes the sociology of race and ethnicity, social inequality, and crime and punishment. He also works with the RROCI, the Restoring Rights and Opportunities Coalition of Illinois, working with and for people with records, advocating for the expansion of opportunities for people with records, and broader criminal justice reform in Illinois proper.

Offering introductory remarks to this panel is Agnes Gund, a world-renowned philanthropist and collector of modern and contemporary art, who launched the Art for Justice Fund in 2017 in partnership with the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors to support criminal justice reform in the United States.

Gund serves on the boards of the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Foundation for Art and Preservation and Embassies, and the Morgan Library & Museum. She is also the co-founder and chair of the Center for Curatorial Leadership, as well as an honorary trustee of the National YoungArts Foundation, Independent Curators International, a very close partner of EXPO Chicago, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland.

EXPO Chicago is thrilled to partner with Agnes and the entire Art for Justice team on this programme, and we welcome you to this cross-disciplinary conversation on art and collective action.

Agnes GundAs a fellow Midwesterner and art lover, I am grateful to EXPO Chicago for inviting me to be part of today's programme about freedom. It is a profound subject, especially now given the current state of the world.

A few years ago, I sold one of my favourite paintings, Roy Lichtenstein's Masterpiece (1962), and contributed the proceeds to launch the Art for Justice Fund. The aim of the Fund is to fuel policy change and creative work to disrupt mass incarceration and promote safe and healthy communities. Thanks to people like lawyer Bryan Stevenson, writer Michelle Alexander, and filmmaker Ava DuVernay, I learned that America's justice system is badly broken: that it preys on people of colour and the poor, that black children are five times as likely to be incarcerated as white children.

AGSince 2017, the Fund has invested nearly USD 75 million dollars in organisations and individuals that are transforming the justice system, such as Illinois Humanities and Heartland Alliance. I am looking forward to hearing from Gabrielle Lyon and Quintin Williams, two extraordinary local partners.

The capacity to heal individuals, families, communities, and our democracy is ignited by our collective actions.

AGArt for Justice grantees help keep people out of jails and prisons via justice reinvestment: shifting government funds away from locked facilities to aid neighbourhoods hardest hit by poverty, violence, and over-policing. They reform excessive sentences and incarceration laws. They help returning citizens to build stability—this is very important. The Fund also supports artists to tell stories about parents, spouses, children, and friends who are caught behind bars and to show the human impact of mass incarceration.

AGIt goes without saying that 2020 has been a difficult year. I also feel encouraged about opportunities to confront racism and build a more equitable America. One thing that has sustained me is being part of the Art for Justice Fund family. Joining with advocates, artists, and aligned donors, our approach uses proceeds from art sales and other contributions to secure a future of shared safety for all.

I'd like to thank Nick Cave and Bob Faust for donating part of the proceeds from their stunning print to benefit the Fund's work. I've been a fan of Nick's fabric sculptures and performance art for more than ten years.

AGI especially love his 'Soundsuits'—their extraordinary scale, colour, and vibrancy—and the wonderful programme that he did at Grand Central Terminal in New York (HEARD•NY, 25–31 March 2020). Some of you may have seen it—it was just extraordinary. [The performers] were all dressed as horses. I had my children go see it later, because it was one of the best things that has happened there.

I would like to close with a quote from the esteemed Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She said, 'Real change, enduring change, happens one step at a time.' Together let's keep fighting for freedom. The capacity to heal individuals, families, communities, and our democracy is ignited by our collective actions.

SCThank you Agnes. To start, I wanted to ask Nick and Bob to give a sense of the print that we are talking about. The print was published by Landfall Press, which was the original printer for the first Chicago International Art Exposition, which, in the 1980s, was the first art fair in North and South America, so it really taps into this legacy, but it also does so much more than that.

Could you start with some of the ideas behind the imagery and the print and what that meant for you?

BFI think when [EXPO Chicago president and director] Tony Karman first approached us to bring the iconic print series back to the fair it was immediately clear to us that we needed to start with the studio's most iconic works: the 'Soundsuits'. Where that was going to go, we were not quite sure; we just knew that was the starting point.

NCAnd to think about post-Rodney King, which was almost three decades ago, in relation to the situation we see ourselves in today—it was important to look at the body of work and to think about what it meant to bring it to this two-dimensional format. So it was about looking at the work and realising that it was really about how we talk about hiding gender, race, and class, and looking at something without judgement.

This was really the catalyst, the starting point. That's how we came to this particular image of the body shrouded with this extraordinary headdress. We were looking at that and saying, 'I see you'.

BFFor the poster, we chose a detailed image that can have many readings. It is focused on this figure adorned with a headpiece, which is actually constructed from a burial wreath. The image becomes even more complicated by the reveal of the naked torso that lets us enter the complicated chemistries of strength and beauty, as well as vulnerability, all at the same time.

So much of it is about art being a way in, to crack that door open, so we can talk about things that are hard or scary.

When we went back to find the original image, it was really important for this to translate from three to two dimensions. We knew it could not be a simple reproduction of a 'Soundsuit'—you'll never understand the feeling, gravity, or weight of a sculptural work in a simple photographic format that reminds you of what the real thing is. So we needed to make an artwork on its own, born from that body of Nick's work, but also reflective of his materiality in its own way.

SCThe way that you both are talking about this idea of translation from performance in the body to an image is a process that is mirrored in these mission-driven organisations and the work that we all have to do. Starting from the very real and the concrete to distilling that information into something that we can read and connect to.

I wanted to move on to Quintin Williams and Gabrielle Lyon to give a little bit of a sense of the missions of their respective organisations. Quintin, maybe a good place to start is how some of the ideas in these works relate to the work that you have been doing with Heartland Alliance and the campaign Fully Free: To End Permanent Punishments. 'Permanent punishments' is a term that you really coined.

QWThank you for that question. The work relates to some things that Nick and Bob were discussing, and as they were talking, I kept thinking about humanity and the essence of being human.

Heartland Alliance is a human rights organisation that is over 100 years old, and we try to highlight and fight for those human rights in a number of ways. My work falls within the realm of the criminal legal system where individuals are chained, if you will, in a number of ways. The way that I describe the work that I do is quite simply that we are trying to dismantle 'the prison', after the prison.

When you talk about the essence of humanity and the various aspects, dimensions, and complexities of it, that drew my attention to one of our core foundational ideas and principles about the campaign—to pass legislation, and make sure that laws are off the books.

We also want to call attention to the humanity that has been stripped from individuals who have been entangled in the criminal legal system and continue to be entangled by it. When we think about humanity and about whose bodies are wrapped up in the grips of the justice system, it makes me think about the importance of this work.

Freedom is about creating space, creating projects, that allow us to live in this world of hope and optimism, yet talk about these very destructive and complex unjust systems.

The essence of being fully free is to be fully recognised as a human. There are other things that come along with that, but one thing that Nick said that I think will stick with me is, 'I see you.' When individuals are dehumanised by any system, but in particular the criminal legal system, I think that it is in effect saying to us on paper and in a number of ways in daily life, that we don't see you.

SCGabrielle, could you speak a little bit about your work with Illinois Humanities?

GLIt really is a privilege to be in community with all of you and under the very generous umbrella of Art for Justice, whose name says it all. Illinois Humanities has been around for, not as long as the extraordinary Heartland Alliance, but for more than 40 years.

At the heart of our work is what it means to ensure access to the humanities. The way we do that is through free programmes that bring people together. We make grants most often to organisations with small budgets where the mission is really driving what it means to make art and use humanities to build community. I think closest to our heart and soul is this idea of enabling conversation and community to strengthen civic engagement.

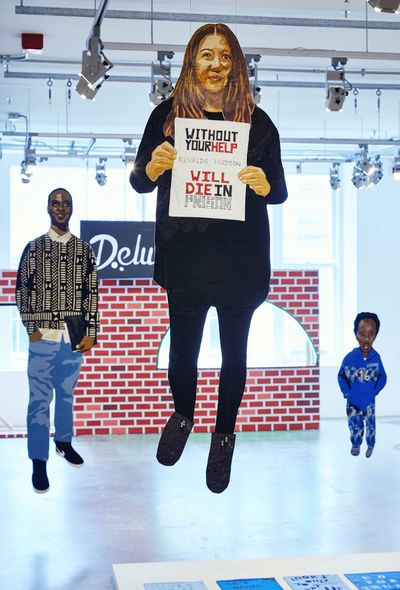

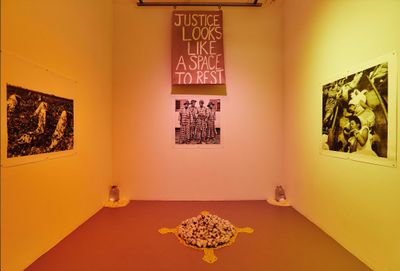

So what does that have to do with Envisioning Justice? This is exactly what Quintin just said. This is so much about the ways in which the carceral system has made—by design—invisibility central. Envisioning Justice enables the arts and the humanities to make visible what is invisible by putting the experiences of people most impacted at the centre of the work.

We have been a recipient from Art for Justice for an Envisioning Justice initiative, which is about doing everything we can to leverage the power of the arts and humanities to shift the conversation and to make visible what it means to take away freedom: what that feels like, and to help people imagine together what alternative possibilities are.

I really love the way Bob and Nick speak about unpacking the nuanced layers of a single, two-dimensional piece of paper. That is the level of conversation that we need to have if we are really going to be able to imagine freedom. Because injustice has been so normalised, oppression and dehumanisation have been normalised. It is almost impossible to imagine the language for alternatives.

What is really great about you unpacking your print is you are helping us have the language to name what we see; to think about how to connect. When you talked about being genderless or not having an immediate assumption imposed: that is what freedom is.

To me, this conversation is really about recognising that it is not enough to ensure access; to just say it is there. You really have to have a collective experience towards freedom, and that requires imagination and imagination is hard work. That is why we need artists and that is why we need humanists. That is what helps us get beyond what we know.

Experiencing alternatives is critical for us to be able to develop and practice moral imagination—to understand what is right and to know what our part is to play.

BFSo much of it is about art being a way in, to crack that door open, so we can talk about things that are hard or scary. That is what Amends was intended to do. We used the public space outside of Facility, at a public school, on the front lawn, to create a clothesline, where anybody in Chicago could come whenever they wanted over the course of the summer to reflect upon their own roles within racism, their own contributions to that, and acknowledge it in themselves and then air them to the world. The thoughts and admissions were written on yellow ribbons that were then attached to the clothesline.

This is really cool for the person who's writing it, because there is an acknowledgement within that individual. But more importantly, what was interesting to us, was that younger people seeing a community clotheslines of these apologies of this magnitude could then have the power to go home to the dinner table and say, 'Hey, there are all these people in our neighbourhood and in our city that are saying this.'

They probably did not have that strength prior to knowing there are others out there willing to stand with them. So it is about the public acknowledgement that allows stuff to shift.

SCInvisibility is not an option. When you look at a Nick Cave and Bob Faust collaboration or any of Nick's performances, the visibility is so pronounced. But there is also a sort of masking that happens, too. I am thinking about the 'Soundsuits' or even with this print—that what you see is not necessarily the face of the individual or the body of the individual but an essence that is freer, more expressive, and potentially unattached to the confines of the body.

In terms of what Quintin said referring to the body as the prison after the prison—that after incarceration and being reintroduced into a society you are still within the prison of a body—I am wondering if Nick and Bob could talk about what freedom of the body actually means, whether through race, gender, or class, and this idea of masking in order to be freer?

NCWhen you look at that print, there is a darkness that is very present. There is a sort of sense of oppression. But then there is colour that is finding its way through.

When I think about freedom, I think about having the ability, this sort of extraordinary privilege, to be able to use my platform to talk about and to reflect on what is currently going on in the world. To me that is what freedom is.

Being able to use this platform to share, collaborate, inform, and open up a dialogue that needs to continuously be ongoing. I think about Rodney King—that is almost three decades ago. Yet we are still talking about the same thing today.

Freedom is about creating space, creating projects, that allow us to live in this world of hope and optimism, yet talk about these very destructive and complex unjust systems.

SCQuintin, I am wondering if you could speak a little bit more about the notion of 'the prison after the prison'. It was such a beautiful line, but also one that I think has a lot of resonance, in terms of how we can define a body either abstractly or in very real ways of moving through the world. For example, the work that Heartland Alliance is doing with Fully Free.

QWSo many things were coming up for me as you all were talking. I think Stephanie you said invisibility is not an option. There is a bit of a common narrative with 'the prison after the prison', and the way that crime, or accusations of crime, are handled.

That is, that you do something, and the good guys come get you and then you go and serve a sentence that is justly adjudicated and then you will be rehabilitated once you are on the inside. Then you are rehabilitated by the state and then they send you home to live your life. But it does not go like that.

What I mean by 'the prison after the prison'—and why that invisibility line spoke so much to me—is people who find themselves in jails or prisons are quite literally confined. There is a material structure: bars, guards, so on and so forth. Then you are released and there appears to be a level of freedom, but then there are all of these invisible chains that people find themselves in that are very subtle and hard to see.

Seeing with new eyes and thinking about alternatives to mass incarceration takes bold imagination.

One of the goals of the project is to highlight that, which is why we changed the language from 'collateral consequences' to 'permanent punishments', because 'collateral consequences' sounds very technical and accidental, after the fact-ish. 'Permanent punishments' resonates with people because that is exactly what they experience. They experience this punishment culture indefinitely. What makes it even more egregious is that we know, because of the disparities, that this impacts black folks in particular.

Nick mentioned Rodney King—that is the front end of the system, right, the first contact with the state. But then you have what is happening on the inside. What our project is about is the extension of punishment into communities, into people's homes by way of electronic monitoring sometimes.

In the answer to this question, by using myself as an example, I spent a lot of my teens and twenties under some type of correctional control—meaning supervision, probation, parole, jail, prison. I experienced all of that in my life.

I remember the last stint where I was in the belly of the beast, if you will. I returned home and did not even know the invisible shackles that I had on me until I went to fill out a rental application, until I went to fill out an employment application, until I tried to apply for life insurance, until I had to go and meet with the counselor and talk about whether this profession is a good fit for me because I cannot get the license.

I was exposed to all of these chains that I thought would be gone once I walked out of prison. It creates this very vicious cycle. By being locked out of opportunities, we are effectively in prison in our own communities. This then creates the conditions by which people return to that very material structure and the cycle goes on and on. That is why our efforts will be in vain if we abolish the prison.

SCI want to touch on some of the very real ways that the campaign Fully Free is rewriting some of these policies and guidelines. But first Gabrielle, could you talk about Envisioning Justice, because I think that specific initiative touches on a lot of what Quintin was just saying.

GLFirst of all, Quintin, thank you for sharing that and reminding us of not only your humanity but the reality of how these things intersect. Envisioning Justice is what we are experiencing right now.

First, simply by having the beautiful excuse of Bob and Nick's work to come together, we are convening a community. I do not know how many people are tuning in right now, but my guess is some might be artists, some may have had first-hand experience or loved ones who were arrested or brutalised by police, or who in fact hold some of the chains in their hands that keep people from being able to get an apartment or being able to apply for a job.

At the heart of it, Envisioning Justice is using arts and humanities as a way to bring people together to imagine alternatives. Part of what Envisioning Justice has done over the last three years has been to work very closely in Chicago, initially with seven community hubs, with extraordinary organisations who do the work of unshackling—incredible organisations like Free Write, writing with young people, or Open Arts, hosting art as therapy, or Let Us Breathe collective, creating space for shared experiences.

Envisioning Justice has also been committed to supporting a network as a way for people to come together—all of which we've been able to do under the extraordinary leadership and guidance of Jane Beachy, our artistic director, and Tyreece Williams, the project manager.

We culminated the first phase of the initiative in an exhibition at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago of 12,000-square feet curated by the incredible curator, Alexandria Eregbu. We created a physical space like the virtual space we are having right now. Thousands of people went through that.

Flash forward: we are now extending the deep partnerships here in Chicago across the state. Because do you know where prisons are? Far away, hard to get to, not connected by public transportation. You know what happens when someone like my godson is arrested and moves from county to prison? He is hard to get to and hard to call, and it's all expensive. Envisioning Justice is about illuminating this kind of reality and infusing dollars into organisations and artists to make and share work.

Envisioning Justice is about public experience. If people are in the audience who are landlords, who oversee insurance, who can commission artwork, who can take the artwork in their homes and bring it outside—do those things! That is part of what it means to envision justice.

Freedom will not be possible without imagination. It can be really, really hard to imagine beyond what we know and what we find familiar. Experiencing alternatives is critical for us to be able to develop and practice moral imagination—to understand what is right and to know what our part is to play.

SCWhen we originally planned this conversation, none of us knew the context in which we would be having it—with no justice for Breonna Taylor, and everything that is going on. This is a context that has to be contended with, and that can be contended with, through the types of work that we are discussing.

The Let Go, a very large project by Nick and Bob was supposed to happen this year, about 'letting go' and 'freedom'. In the context of amends and what Quintin and Gabrielle have brought up, it would be really helpful to talk about this piece. It was first shown at the Park Avenue Armory in New York in 2018 and was meant to show at Navy Pier in Chicago this year.

NCThis relates to what Quintin and Gabrielle were discussing. What came to mind is 'the record'. How do we get past the record? That is the shackle for those who are incarcerated. What do we do with that in order for people to come closer to freedom? Because the record is a sort of barrier.

I cannot even talk about The Let Go when I think about it like that. It is sort of contrary to the thoughts that I have around the system. And how do we change that in order for there to be opportunities for those to come to The Let Go and to be free? To move their bodies in this sort of way of release?

BFI think we can talk about The Let Go a little bit in terms of the election coming up. It is very clear we now are all in our bubbles—we are hearing what we want to hear, and we are more divided than we have ever been before.

One of the key concepts of The Let Go was to create a town hall without words, with the belief that if we get rid of words, we can get people in the same space without all the preconceptions generally used as a way to get to know one another. Through movement and body we can express ourselves exactly the way we want to without the triggers of hearing and knowing exactly what I do not like about you, or what I do not like about what you believe in.

We looked at it as a place of release and to be able to feel freedom, but also as a way to come together to hopefully make a few new connections that allow us to talk across some borders that we are building.

SCSo more of an intuitive humanity?

BFKind of.

SCQuintin, what are some of the real ways that the Heartland Alliance is putting forward to end permanent punishments? What are some of the key things that you all are working on right now?

QWWe are working on a number of things. First, we are working on centring the voices of those individuals who are directly impacted by the system, because I often say this: that individuals with records in communities that are on the outskirts of mainstream society are often the objects of policy and programmes, rather than the architects.

One of the things that we wanted to do with this campaign is to ensure that we had the right architects at the table to help us build something. That's what we have been doing—building that groundswell of individuals who have been left out and locked out. We have been really building that base of individuals.

Secondly, we have been working on our communications and narrative change, because there are a lot of things that we need to reframe. We need to reframe what it means to be a person with a record in the first place.

Nick talked about the record—that negative credential in a credential society. We have these credentials that get us access to places, but this happens to be a credential that bars you from places. There rests an assumption about people with records as threats, as dangerous, as people who are different than the general public—different than 'normal humans'.

The other thing that we are trying to do and have been doing is to develop these messages to counter the harmful messages that we have seen re-emerge since Covid-19, as a result of de-carceration efforts and individuals not being allowed to come home based on offenses. We have been working on that.

We have also been thinking about what our strategy will be legislatively, because the truth of the matter is that in Illinois, there are 118 laws in the areas of employment, housing, and education that bar people from access to things that will contribute to their thriving and flourishing. We are currently developing that strategy, building a broader coalition of organisations, like-minded individuals, allies, and even unlikely allies, because we need this to be a collective effort. We are getting our ducks in a row.

Freedom is an act that requires collective effort on many people's part, for each of us to contribute to being free.

I often say that policies speak; what is on paper says something. I know Nick and Bob have attested that things on paper say things to us. Policies that might say, 'No, you are the kind of person that we have categorised you as. You are not allowed here.' That says something to you, and it speaks very loudly to a lot of individuals of colour in this country. We are trying to erase them, literally erase them, so that that record can no longer speak to individuals negatively.

I am very grateful to collaborate with artists to really bring some of these ideas about freedom to life. The notion of being fully free, what does that even mean? The implication is that individuals are not fully free. There is a little glimpse of freedom, a toe in the water. We want to go swimming in the full ocean of freedom. That is what we have been doing for this first year, and then in the subsequent years, we are only going to amplify those things that I just mentioned.

SCThis idea of institutional records has such a polarising definition. It's at the complete opposite end of the spectrum when we are talking about, for example, having your work in a collection within that record, versus another institution where the record is something that will essentially destroy everything.

GLThis conversation is reminding me of something: Chicago and Illinois have a long history of both systemic racism and efforts for abolition. I am just thinking in this moment of how we talk about the record—how it is so important to be able to see through someone else's eyes and understand a different experience to our own.

When Ida B. Wells was writing about the pervasiveness of American terrorism in the form of lynching; she was a data collector, she was a writer, she was a self-publisher, she was a wordsmith. Jane Adams, another Chicago hero and international landmark for us, she was moved to write a response to Ida's work, 'Hey all you people doing lynching, violence is not the answer.' Ida B. Well's response to her was, 'Those people didn't do anything wrong in the first place.'

I am oversimplifying a very complicated narrative. But key to the question of what the record tells us depends on the eyes that we are seeing it through. Part of shifting the narrative—and why the paintbrush and the photograph may be more powerful than, as Quintin says, the pen on paper—is because it does let us see differently, and maybe decentre our own experiences.

SCAbsolutely. With the exception of this print, there is not much two-dimensional work that you both do. Your work is ephemeral in nature. I am thinking of all of the performances that we have collaborated on with the 'Soundsuits' and things like this. It is an experience that sticks with you, but it is not permanent in the same way that perhaps this print is.

BFThat is super interesting, the idea of permanence and how fragile paper is. Of all the materials that we work with, that is probably the one that is the most fragile. I think with every one of the things that you work on or that we work on, the goal is always to create a memory in the moment that travels with you no matter what. Whether that object is in front of you or left behind. Whether that piece of paper is just something you saw and recorded. But it is about memory.

NCIt is a sort of memento. It is an object that sort of holds a moment in time. We can look at this print and think about the time that it was done, for when it was done, and for who it was done. It is interesting to think about it and its role and why it was created, during the time of Breonna Taylor—the marking of this moment again. For us, it really allows us to look back—it may it be a publication, a print, an invitation. These are markers that establish a particular moment.

BFFor its connection to Art for Justice—it is so cool that this was first made to bring back an iconic symbol of Chicago and art, art-making, and gathering. Here we are at one of the hardest moments of our lives, and this print is being used in an entirely new and additional way that is about this moment. I think we have to be very thankful for you guys, EXPO Chicago, for pulling that together, and this conversation. I am very grateful that the print did that.

SCThe print did that and so much more. I can speak from EXPO Chicago's side. Of course, we were renewing this tradition of posters that were made in the 1980s, when the fair was the only fair in North and South America. It had this huge global stature in terms of access and reach, and Chicago was on the map as this global hub, which it still is, of course, but there has been a proliferation of art fairs everywhere.

When you look at the iconic prints that the Chicago fair produced, you will notice a very clear lack of diversity. Working with you to make this was not just to have a print, but also an opportunity to revisit that history and say it exists, we acknowledge that. That captured a moment in how the art world was structured. We want to revise how that is structured, but not ignore the history of how this print is taking place. That is the tradition that it taps into.

I feel like that is why the print, even a year later, feels so recent. Of course, within the realm of both of your practices, it is going to talk to these other issues as they come up. I imagine that we could have the conversation again in six months, unfortunately. It is one of those images that speaks to our current moment.

GLIt is maybe also good to remember that in this current moment, art is being made by artists who are bringing their name and talent to places where they might not have otherwise.

Vice versa, artists that we might not have seen otherwise, have a platform and opportunity to create work in public spaces and to make the invisible, visible—memorialising places that matter, and reminding us that freedom is not just when you walk out. Freedom is an act that requires collective effort on many people's part, for each of us to contribute to being free.

I think that's one of the extraordinary things about the timing of this conversation, and what it means to make art for justice.

SCFor the audience, what are some of the ways that everybody can get involved with the work that you are doing?

QWYou can definitely reach out to me at [email protected]. Or you can go and look up our Never Fully Free Report, which outlines the scale and scope of permanent punishment in Illinois.

I think the report also has some very practical, tangible things that individuals can do besides connecting with me directly. But I really would love to connect with people—I love to connect with groups and organisations and individuals because, again, this is going to be a collective effort. I love what Gabrielle said, that in freedom there is a connectivity that has to go along with freedom. Freedom does not happen in isolation. Please check out our report and connect with me.

SCGabrielle, I know that a lot of our audience may have seen the Envisioning Justice exhibition when it was on view of the Sullivan Galleries at the School of Art Institute of Chicago, so that is an obvious entrée, but what are some of the ways that people can get involved with Illinois Humanities as well?

GLSince we cannot be together physically, we bring people together in a regular video series called Rapid Response. You can tune into that. Our next one is coming up in a month. If you are on the ilhumanities.org email list, you will find out about Rapid Response.

Back to Quintin's phrasing, we are centring the voices of people who have the most experience and have been impacted by the terrible impacts of the carceral system. Artists, poets, performers, and a real framing of the conversation of the moment. Rapid Response, like all of our Illinois Humanities programmes, is free.

The second thing is to look around where you are at in your community. If you notice art, ask who did that and what that represents. My guess is no matter where you are, art is happening. Seeing with new eyes and thinking about alternatives to mass incarceration takes bold imagination. If a phrase like 'Defund the Police' or 'Abolish Prisons' is the phrase that gets you thinking, 'What would that take?' or 'What would that look like?' you are exercising an act of radical imagination.

We certainly will not get any farther from where we are now unless we can take that leap together, irrespective of what solutions we collectively come up with. Be brave, be bold, and exercise your imagination.

I really want to thank Nick and Bob and Art for Justice for giving us a chance to be together, and Stephanie for your gentle and skilled facilitation—this is a lot for us to think about and talk about together.

SCThank you, Gabe. Nick and Bob, the obvious thing that people can do to get involved is to buy this piece of history and hang it in their homes. Any other closing remarks on how we could work together further on all this?

BFWhen I think of the word freedom, I think of this big, expansive, airy thing. But what I am coming away with is so much meatier. It is the idea that freedom is responsibility. That just takes me right to vote. Make sure everybody that you talk to is doing that. Vote. If we want change, we have got to do it together.

NCYes, and we are not free until we all are free. We are going to keep working hard and being as proactive as we possibly can. It is so extraordinarily refreshing to have these conversations that we can all be part of, and that allow us to reflect and to see ourselves existing in the world differently. It has been amazing just spending this hour and 20 minutes in conversation.